The Editing Structure of Slasher Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Die in a Slasher Film: the Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol

Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol. 21 (Issue 1): pp. 128 – 146 Wellman, Meitl, & Kinkade Copyright © 2021 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture All rights reserved. ISSN: 1070-8286 How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization, Strength, and Flaws on Characters’ Mortality Ashley Wellman Texas Christian University & Michele Bisaccia Meitl Texas Christian University & Patrick Kinkade Texas Christian University 128 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol. 21 (Issue 1): pp. 128 – 146 Wellman, Meitl, & Kinkade Abstract Popular culture has often referenced formulaic ways to predict a character’s fate in slasher films. The cliché rules have noted only virgins live, black characters die first, and drinking and drugs nearly guarantee your death, but to what extent do characters’ basic demographics and portrayal determine whether a character lives or dies? A content analysis of forty-eight of the most influential slasher films from the 1960s – 2010s was conducted to measure factors related to character mortality. From these films, gender, race, sexualization (measured via specific acts and total sexualization), strength, and flaws were coded for 504 non killer characters. Results indicate that the factors predicting death vary by gender. For male characters, those appearing weak in terms of physical strength or courage and those males who appeared morally flawed were more likely to die than males that were strong and morally sound. Predictors of death for female characters included strength and the presence of sexual behavior (including dress, flirtatious attitude, foreplay/sex, nudity, and total sexualization). -

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

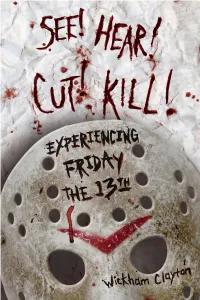

Read an Excerpt

Univer�it y Pre� of Mis �is �ipp � / Jacks o� Contents u Preface: This book could be for you, depending on how you read it . ix. Acknowledgments . .xiii Chapter 1 Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy . 3 Chapter 2 Jason’s Mechanical Eye . 45 Chapter 3 Hearing Cutting . .83 . Chapter 4 Have You Met Jason? . 119. Chapter 5 The Importance of Being Jason . 153 .. Appendix 1 Plot Summaries for the Friday the 13th Films . 179 Appendix 2 List and Description of Characters in the Friday the 13th Films . 185 Works Cited . 199 Index . 217. Chapter 1 u Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy Sometimes the weirdest movies strike you in unexpected ways. In the winter of 1997, I attended a late-night screening of Friday the 13th (1980) at the campus theater at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. I’d never seen the film before, but I was aware of its cultural significance. I expected a generic slasher film with extensive violence and nudity. I expected something ultimately forgettable. Having watched it seventeen years after its initial release, I found it generic; it did have violence and nudity, and was entertaining. However, I did not find it forgettable. Walking home with the first flecks of a winter snow weaving around me in the dark, I found myself thinking over it. I continually recalled images, sounds, and narrative moments that were vivid in my mind. Friday the 13th wormed into my brain, with its haunting and atmospheric style. After watching the original film several more times, I started in on the sequels, preparing myself for disappointment each time. -

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror Barry Keith Grant Brock University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a broad historical overview of the ideology and cultural roots of horror films. The genre of horror has been an important part of film history from the beginning and has never fallen from public popularity. It has also been a staple category of multiple national cinemas, and benefits from a most extensive network of extra-cinematic institutions. Horror movies aim to rudely move us out of our complacency in the quotidian world, by way of negative emotions such as horror, fear, suspense, terror, and disgust. To do so, horror addresses fears that are both universally taboo and that also respond to historically and culturally specific anxieties. The ideology of horror has shifted historically according to contemporaneous cultural anxieties, including the fear of repressed animal desires, sexual difference, nuclear warfare and mass annihilation, lurking madness and violence hiding underneath the quotidian, and bodily decay. But whatever the particular fears exploited by particular horror films, they provide viewers with vicarious but controlled thrills, and thus offer a release, a catharsis, of our collective and individual fears. Author Keywords Genre; taboo; ideology; mythology. Introduction Insofar as both film and videogames are visual forms that unfold in time, there is no question that the latter take their primary inspiration from the former. In what follows, I will focus on horror films rather than games, with the aim of introducing video game scholars and gamers to the rich history of the genre in the cinema. I will touch on several issues central to horror and, I hope, will suggest some connections to videogames as well as hints for further reflection on some of their points of convergence. -

Horror Genre in National Cinemas of East Slavic Countries

Studia Filmoznawcze 35 Wroc³aw 2014 Volha Isakava University of Ottawa, Canada HORROR GENRE IN NATIONAL CINEMAS OF EAST SLAVIC COUNTRIES In this essay I would like to outline several tendencies one can observe in con- temporary horror fi lms from three former Soviet republics: Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. These observations are meant to chart the recent (2000-onwards) de- velopment of horror as a genre of mainstream cinema, and what cultural, social and political forces shape its development. Horror fi lm is of particular interest to me because it is a popular genre known for a long and interesting history in American cinema. In addition, horror is one of transnational genres that infuse Hollywood formula with particularities of national cinematic traditions (most no- table example is East Asian horror cinema, namely “J-horror,” Japanese horror). To understand the peculiarity of the newly emerged horror genre in the cinemas of East Slavic countries, I propose two venues of exploration, or two perspectives. The fi rst one could be called the global perspective: horror fi lm, as it exists today in post-Soviet space, is profoundly infl uenced by Hollywood. Domestic produc- tions compete with American fi lms at the box offi ce and strive to emulate genre structures of Hollywood to attract viewers, whose tastes are largely shaped by American fi lms. This is especially true for horror, which has almost no reference point in national cinematic traditions in question. The second vantage point is local: the local specifi city of these horror narratives, how the fi lms refl ect their own cultural condition, shaped by today’s globalized cinema market, Hollywood hegemony and local sensibilities of distinct cinematic and pop-culture traditions. -

The Final Girl Grown Up: Representations of Women in Horror Films from 1978-2016

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2017 The inF al Girl Grown Up: Representations of Women in Horror Films from 1978-2016 Lauren Cupp Scripps College Recommended Citation Cupp, Lauren, "The inF al Girl Grown Up: Representations of Women in Horror Films from 1978-2016" (2017). Scripps Senior Theses. 958. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/958 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FINAL GIRL GROWN UP: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN HORROR FILMS FROM 1978-2016 by LAUREN J. CUPP SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR TRAN PROFESSOR MACKO DECEMBER 9, 2016 Cupp 2 I was a highly sensitive kid growing up. I was terrified of any horror movie I saw in the video store, I refused to dress up as anything but a Disney princess for Halloween, and to this day I hate haunted houses. I never took an interest in horror until I took a class abroad in London about horror films, and what peaked my interest is that horror is much more than a few cheap jump scares in a ghost movie. Horror films serve as an exploration into our deepest physical and psychological fears and boundaries, not only on a personal level, but also within our culture. Of course cultures shift focus depending on the decade, and horror films in the United States in particular reflect this change, whether the monsters were ghosts, vampires, zombies, or aliens. -

Science Fiction/San Francisco Issue 25 Date: July 5, 2006 Editors: Jean Martin, Chris Garcia Email: [email protected] Copy Editor: David Moyce Layout: Eva Kent

Science Fiction/San Francisco Issue 25 Date: July 5, 2006 Editors: Jean Martin, Chris Garcia email: [email protected] Copy Editor: David Moyce Layout: Eva Kent TOC News and Notes ...........................................Christopher J. Garcia ....................................................................................................3 Letters of Comment .....................................Jean Martin and Chris Garcia ....................................................................................4-6 Editorial .......................................................Jean Martin ................................................................................................................... 7 Ghosts and Surreal Art in Portland ...............Jean Marin ................................Photos Jean Martin ................................................8-11 Nemo Gould Sculptures ...............................Espana Sheriff ...........................Photos from www.nemomatic.com ......................12-13 Reading at Intersection for the Arts ..............Christopher J. Garcia ............................................................................................14-15 Klingon Celebration .....................................Jean Marin ................................Photos by Jean Martin .........................................16-21 BASFA Minutes ..........................................................................................................................................................................22-24 -

Asian Extreme As Cult Cinema: the Transnational Appeal of Excess and Otherness Jessica Anne Hughes BA English and Film Studies

Asian Extreme as Cult Cinema: The Transnational Appeal of Excess and Otherness Jessica Anne Hughes BA English and Film Studies, Wilfrid Laurier University MA Film Studies, University of British Columbia A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Communications and Arts Hughes 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the way Western audiences respond to portrayals of excess and otherness in Japanese Extreme cinema. It explores the way a recent (2006-2016) cycle of Japanese Splatter (J-Splatter) films, including The Machine Girl (Noboru Iguchi, 2008) and Tokyo Gore Police (Yoshihiro Nishimura, 2008), have been positioned as cult due to their over-the-top representations of violence and stereotypes of Japanese culture. Phenomenological research and personal interviews interrogate Western encounters with J-Splatter films at niche film festivals and on DVD and various online platforms through independent distributors. I argue that these films are marketed to particular Western cult audiences using vocabulary and images that highlight the exotic nature of globally recognised Japanese cultural symbols such as schoolgirls and geisha. This thesis analyses J-Splatter’s transnational, cosmopolitan appeal using an approach informed by the work of Ernest Mathijs and Jamie Sexton, Matt Hills, Henry Jenkins, and Iain Robert Smith, who read the relationship between Western audiences and international cult cinema as positive and meaningful cultural interactions, demonstrating a desire to engage in more global experiences. The chapters in this thesis use textual analysis of J-Splatter films and case studies of North American and Australian film festivals and distribution companies, which include interviews with festival directors and distributors, to analyse the nature of the appeal of J- Splatter to Western audiences. -

Looking at Almodovar's Queer Genders and Their

BORDER EPISTEMOLOGIES: LOOKING AT ALMODOVAR’S QUEER GENDERS AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR VISUAL CULTURE EDUCATION By BELIDSON D. BEZERRA JR B.A., Universidade de Brasilia, Brazil, 1989 M.A., Manchester Metropolitan University, U.K., 1992 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Curriculum Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 2006 ©Belidson D. Bezerra Jr, 2006 Abstract The everyday practices of contemporary art education from grades K- 12 are marked by the neglect of the cultural experience of film and the disregard for issues of gender as well as the concealment of issues of sexuality. So it is in the confluence of visual culture, queer theory, art education and film studies that I posit my inquiry. I explore theoretical frameworks for understanding how we look at queer representations of gender and sexuality in visual culture, particularly focusing on Pedro Almodóvar’s filmography and its impact for the teaching and learning of visual culture in higher education and in secondary schools. The organizing questions are: How do Pedro Almodóvar’s film representations of queer sexuality and gender inform contemporary art education theory and practice? In what ways is the utilization of border epistemologies relevant for understanding representations of genders and sexualities in Almodóvar’s films? How does it inform art education practices? Also, this study fills a gap in the emerging critical literature in art education because, as a study focusing on queer visual representation and border epistemologies, it will consider intersections among these specific sites of knowledge, and such studies are rare in the field. -

A Historical Approach to the Slasher Film Below Halloween (1978)

Articles A Historical Approach to the Slasher Film Below Halloween (1978) The Classical Period, the Post-slasher A Historical Films, and the Neoslashers Approach to the By Sotiris Petridis Keywords slasher films, neoslashers, Slasher Film postmodern horror, Carol Clover, final girl, Vera Dika Horror films are one of the most popular genres in Many academic texts, including Dika’s analysis, Hollywood and constitute an integral part of pop cul- argue that Halloween (1978) is the starting point of ture. The horror genre made its appearance almost slasher films. Of courseHalloween is a milestone for at the same time cinema was born and numerous the whole subgenre and it perfectly combines all subgenres were created after that time. Some exam- of its conventions. However, four years before that, ples are the demonic movies, the vampire films and there were another two films which belong to the the splatter films. One of the most well-known and slasher subgenre. In 1974, Black Christmas and The important subgenres of horror is the slasher film. Texas Chainsaw Massacre came into theatres and set In this article I will argue that there are three basic some basic rules for the subgenre’s formula. There- periods in the lifetime of slasher films: the classical fore, I would argue that the starting point of the period; the postmodern period; and the neoslashers. subgenre is 1974. Naturally, even before that, there The classical period starts in 1974 and lasts until the were some films that had influenced the slasher end of the 1980s; the postmodern period takes place in the 1990s; and neoslashers started to evolve in the beginning of the new millennium. -

Sexuality in the Horror Soundtrack (1968-1981)

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Monstrous Resonance: Sexuality in the Horror Soundtrack (1968-1981) A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Morgan Fifield Woolsey 2018 © Copyright by Morgan Fifield Woolsey 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Monstrous Resonance: Sexuality in the Horror Soundtrack (1968-1981) by Morgan Fifield Woolsey Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Raymond L. Knapp, Co-Chair Professor Mitchell Bryan Morris, Co-Chair In this dissertation I argue for the importance of the film soundtrack as affective archive through a consideration of the horror soundtrack. Long dismissed by scholars in both cinema media studies and musicology as one of horror’s many manipulative special effects employed in the aesthetically and ideologically uncomplicated goal of arousing fear, the horror soundtrack is in fact an invaluable resource for scholars seeking to historicize changes in cultural sensibilities and public feelings about sexuality. I explore the critical potential of the horror soundtrack as affective archive through formal and theoretical analysis of the role of music in the representation of sexuality in the horror film. I focus on films consumed in the Unites States during the 1970s, a decade marked by rapid shifts in both cultural understanding and cinematic representation of sexuality. ii My analyses proceed from an interdisciplinary theoretical framework animated by methods drawn from affect studies, American studies, feminist film theory, film music studies, queer of color critique, and queer theory. What is the relationship between public discourses of fear around gender, race, class, and sexuality, and the musical framing of sexuality as fearful in the horror film? I explore this central question through the examination of significant figures in the genre (the vampire, the mad scientist/creation dyad, and the slasher or serial killer) and the musical-affective economies in which they circulate. -

UNIT 4 CINEMA the Cinema, Like the Detective Story, Makes It Possible To

UNIT 4 CINEMA The cinema, like the detective story, makes it possible to experience without danger all the excitement, passion and desirousness which must be repressed in a humanitarian ordering of life. Carl Jung Before you start doing the main activities of this unit, brush up on active vocabulary to the topic. Exercise 1. Answer t:e following questions: 1. Do you like watching films? Why? / Why not? How often do you… a) go to the cinema, b) rent DVDs, c) buy DVDs, d) watch films on TV? 2. What’s your favourite film? Why do you like it? Who stars in it? Who directed it? How many times have you seen it? Does it hold any special memories for you? Can you tell the plot in thirty seconds? What genre(s) of films do you a) love, b) hate? Why 3. Have you got a video camera? What do you use it for? Why do people make home movies? Which is more special, a home movie or a photo? Why? 4. Would you like to work in the film industry? Why? / Why not? Which job(s) do you think are the most rewarding? Why? Do you prefer to watch films made in your country, or Hollywood movies? Why? 5. Have you ever downloaded a film from the internet – either legally or illegally? How do you prefer to watch films, and why? Have you ever watched a film on… a) a plasma TV, b) a very large IMAX screen, c) an iPod? Compare these experiences to watching films on a normal TV.