NREL Has Learned Over the Past 20 Years About Variouwcommunity-Based Learning Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TR-SBA-Research-0512-01: Fast and Efficient Browser Identification With

Fast and Efficient Browser Identification with JavaScript Engine Fingerprinting Technical Report TR-SBA-Research-0512-01 Martin Mulazzani∗, Philipp Reschl; Markus Huber∗, Manuel Leithner∗, Edgar Weippl∗ *SBA Research Favoritenstrasse 16 AT-1040 Vienna, Austria [email protected] Abstract. While web browsers are becoming more and more important in everyday life, the reliable detection of whether a client is using a specific browser is still a hard problem. So far, the UserAgent string is used, which is a self-reported string provided by the client. It is, however, not a security feature, and can be changed arbitrarily. In this paper, we propose a new method for identifying Web browsers, based on the underlying Javascript engine. We set up a Javascript confor- mance test and calculate a fingerprint that can reliably identify a given browser, and can be executed on the client within a fraction of a sec- ond. Our method is three orders of magnitude faster than previous work on browser fingerprinting, and can be implemented in just a few hun- dred lines of Javascript. Furthermore, we collected data for more than 150 browser and operating system combinations, and present algorithms to calculate minimal fingerprints for each of a given set of browsers to make fingerprinting as fast as possible. We evaluate the feasibility of our method with a survey and discuss the consequences for user privacy and security. This technique can be used to enhance state-of-the-art session management (with or without SSL), as it can make session hijacking considerably more difficult. 1 Introduction Today, the Web browser is a central component of almost every operating sys- tem. -

The Artist's Emergent Journey the Metaphysics of Henri Bergson, and Also Those by Eric Voegelin Against Gnosticism2

Vol 1 No 2 (Autumn 2020) Online: jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/nexj Visit our WebBlog: newexplorations.net The Artist’s Emergent Journey Clinton Ignatov—The McLuhan Institute—[email protected] To examine computers as a medium in the style of Marshall McLuhan, we must understand the origins of his own perceptions on the nature of media and his deep-seated religious impetus for their development. First we will uncover McLuhan’s reasoning in his description of the artist and the occult origins of his categories of hot and cool media. This will prepare us to recognize these categories when they are reformulated by cyberneticist Norbert Wiener and ethnographer Sherry Turkle. Then, as we consider the roles “black boxes” play in contemporary art and theory, many ways of bringing McLuhan’s insights on space perception and the role of the artist up to date for the work of defining and explaining cyberspace will be demonstrated. Through this work the paradoxical morality of McLuhan’s decision to not make moral value judgments will have been made clear. Introduction In order to bring Marshall McLuhan into the 21st century it is insufficient to retrieve his public persona. This particular character, performed in the ‘60s and ‘70s on the global theater’s world stage, was tailored to the audiences of its time. For our purposes today, we’ve no option but an audacious attempt to retrieve, as best we can, the whole man. To these ends, while examining the media of our time, we will strive to delicately reconstruct the human-scale McLuhan from what has been left in both his public and private written corpus. -

Instrumentalizing the Sources of Attraction. How Russia Undermines Its Own Soft Power

INSTRUMENTALIZING THE SOURCES OF ATTRACTION. HOW RUSSIA UNDERMINES ITS OWN SOFT POWER By Vasile Rotaru Abstract The 2011-2013 domestic protests and the 2013-2015 Ukraine crisis have brought to the Russian politics forefront an increasing preoccupation for the soft power. The concept started to be used in official discourses and documents and a series of measures have been taken both to avoid the ‘dangers’ of and to streamline Russia’s soft power. This dichotomous approach towards the ‘power of attraction’ have revealed the differences of perception of the soft power by Russian officials and the Western counterparts. The present paper will analyse Russia’s efforts to control and to instrumentalize the sources of soft power, trying to assess the effectiveness of such an approach. Keywords: Russian soft power, Russian foreign policy, public diplomacy, Russian mass media, Russian internet Introduction The use of term soft power is relatively new in the Russian political circles, however, it has become recently increasingly popular among the Russian analysts, policy makers and politicians. The term per se was used for the first time in Russian political discourse in February 2012 by Vladimir Putin. In the presidential election campaign, the then candidate Putin drew attention to the fact that soft power – “a set of tools and methods to achieve foreign policy goals without the use of arms but by exerting information and other levers of influence” is used frequently by “big countries, international blocks or corporations” “to develop and provoke extremist, separatist and nationalistic attitudes, to manipulate the public and to directly interfere in the domestic policy of sovereign countries” (Putin 2012). -

Background Setup

1.5.09 [email protected] Mechanical Turk/Browser Ballot Findings Background To compliment the testing and research done by Critical and Patrick Finch in Europe, I conducted a series of tests on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to try out various aspects of the EC's Ballot design. The goal is to determine both how to design the ballot in the most neutral way possible, and for Mozilla to determine the most successful summary and image for the Firefox section of the ballot. I used MT because it’s a very fast and cheap way to get a design in front of many eyes. And the responses that came back were very good; users spent an average of 2.8 minutes on a five- minute test, and gave complete answers to free-form questions. A few drawbacks of the test were: • Users tended to be more highly-technical than average • Users tended to have heard of Firefox and already have a favorable opinion about it • MT did not provide a way to filter results by country, and many users were in North America as a result Because of the above problems, the MT tests are not the best sample of users that are similar to those seeing the ballot in Europe. However, their answers still provided some insight into why people use what browsers, what factors would make them switch, and what presentations of Firefox’s brand and motto would be most compelling. Setup The MT tests were given in three phases. In all of these test, various demographics questions such as what browser the user was running and where they live were asked. -

HOLT Earth Science

HOLT Earth Science Directed Reading Name Class Date Skills Worksheet Directed Reading Section: What Is Earth Science? 1. For thousands of years, people have looked at the world and wondered what shaped it. 2. How did cultures throughout history attempt to explain events such as vol- cano eruptions, earthquakes, and eclipses? 3. How does modern science attempt to understand Earth and its changing landscape? THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF EARTH ______ 4. Scientists in China began keeping records of earthquakes as early as a. 200 BCE. b. 480 BCE. c. 780 BCE. d. 1780 BCE. ______ 5. What kind of catalog did the ancient Greeks compile? a. a catalog of rocks and minerals b. a catalog of stars in the universe c. a catalog of gods and goddesses d. a catalog of fashion ______ 6. What did the Maya track in ancient times? a. the tides b. the movement of people and animals c. changes in rocks and minerals d. the movements of the sun, moon, and planets ______ 7. Based on their observations, the Maya created a. jewelry. b. calendars. c. books. d. pyramids. Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved. Holt Earth Science 7 Introduction to Earth Science Name Class Date Directed Reading continued ______ 8. For a long time, scientific discoveries were limited to a. observations of phenomena that could be made with the help of scientific instruments. b. observations of phenomena that could not be seen, only imagined. c. myths and legends surrounding phenomena. d. observations of phenomena that could be seen with the unaided eye. -

Computational Propaganda in Russia: the Origins of Digital Misinformation

Working Paper No. 2017.3 Computational Propaganda in Russia: The Origins of Digital Misinformation Sergey Sanovich, New York University 1 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction.......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Domestic Origins of Russian Foreign Digital Propaganda ......................................................................... 5 Identifying Russian Bots on Twitter .............................................................................................................. 13 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................................... 15 Author Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................ 17 About the Author ............................................................................................................................................. 17 References ........................................................................................................................................................ 18 Citation ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Webkit and Blink: Open Development Powering the HTML5 Revolution

WebKit and Blink: Open Development Powering the HTML5 Revolution Juan J. Sánchez LinuxCon 2013, New Orleans Myself, Igalia and WebKit Co-founder, member of the WebKit/Blink/Browsers team Igalia is an open source consultancy founded in 2001 Igalia is Top 5 contributor to upstream WebKit/Blink Working with many industry actors: tablets, phones, smart tv, set-top boxes, IVI and home automation. WebKit and Blink Juan J. Sánchez Outline The WebKit technology: goals, features, architecture, code structure, ports, webkit2, ongoing work The WebKit community: contributors, committers, reviewers, tools, events How to contribute to WebKit: bugfixing, features, new ports Blink: history, motivations for the fork, differences, status and impact in the WebKit community WebKit and Blink Juan J. Sánchez WebKit: The technology WebKit and Blink Juan J. Sánchez The WebKit project Web rendering engine (HTML, JavaScript, CSS...) The engine is the product Started as a fork of KHTML and KJS in 2001 Open Source since 2005 Among other things, it’s useful for: Web browsers Using web technologies for UI development WebKit and Blink Juan J. Sánchez Goals of the project Web Content Engine: HTML, CSS, JavaScript, DOM Open Source: BSD-style and LGPL licenses Compatibility: regression testing Standards Compliance Stability Performance Security Portability: desktop, mobile, embedded... Usability Hackability WebKit and Blink Juan J. Sánchez Goals of the project NON-goals: “It’s an engine, not a browser” “It’s an engineering project not a science project” “It’s not a bundle of maximally general and reusable code” “It’s not the solution to every problem” http://www.webkit.org/projects/goals.html WebKit and Blink Juan J. -

WORLD WAR C : Understanding Nation-State Motives Behind Today’S Advanced Cyber Attacks

REPORT WORLD WAR C : Understanding Nation-State Motives Behind Today’s Advanced Cyber Attacks Authors: Kenneth Geers, Darien Kindlund, Ned Moran, Rob Rachwald SECURITY REIMAGINED World War C: Understanding Nation-State Motives Behind Today’s Advanced Cyber Attacks CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 A Word of Warning ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 The FireEye Perspective ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Your Post Has Been Removed

Frederik Stjernfelt & Anne Mette Lauritzen YOUR POST HAS BEEN REMOVED Tech Giants and Freedom of Speech Your Post has been Removed Frederik Stjernfelt Anne Mette Lauritzen Your Post has been Removed Tech Giants and Freedom of Speech Frederik Stjernfelt Anne Mette Lauritzen Humanomics Center, Center for Information and Communication/AAU Bubble Studies Aalborg University University of Copenhagen Copenhagen København S, København SV, København, Denmark København, Denmark ISBN 978-3-030-25967-9 ISBN 978-3-030-25968-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25968-6 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permit- ted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Webkit and Blink: Bridging the Gap Between the Kernel and the HTML5 Revolution

WebKit and Blink: Bridging the Gap Between the Kernel and the HTML5 Revolution Juan J. Sánchez LinuxCon Japan 2014, Tokyo Myself, Igalia and WebKit Co-founder, member of the WebKit/Blink/Browsers team Igalia is an open source consultancy founded in 2001 Igalia is Top 5 contributor to upstream WebKit/Blink Working with many industry actors: tablets, phones, smart tv, set-top boxes, IVI and home automation. WebKit and Blink Juan J. Sánchez Outline 1 Why this all matters 2 2004-2013: WebKit, a historical perspective 2.1. The technology: goals, features, architecture, ports, webkit2, code, licenses 2.2. The community: kinds of contributors and contributions, tools, events 3 April 2013. The creation of Blink: history, motivations for the fork, differences and impact in the WebKit community 4 2013-2014: Current status of both projects, future perspectives and conclusions WebKit and Blink Juan J. Sánchez PART 1: Why this all matters WebKit and Blink Juan J. Sánchez Why this all matters Long time trying to use Web technologies to replace native totally or partially Challenge enabled by new HTML5 features and improved performance Open Source is key for innovation in the field Mozilla focusing on the browser WebKit and now Blink are key projects for those building platforms and/or browsers WebKit and Blink Juan J. Sánchez PART 2: 2004-2013 WebKit, a historical perspective WebKit and Blink Juan J. Sánchez PART 2.1 WebKit: the technology WebKit and Blink Juan J. Sánchez The WebKit project Web rendering engine (HTML, JavaScript, CSS...) The engine is the product Started as a fork of KHTML and KJS in 2001 Open Source since 2005 Among other things, it’s useful for: Web browsers Using web technologies for UI development WebKit and Blink Juan J. -

Building a Browser for Automotive: Alternatives, Challenges and Recommendations

Building a Browser for Automotive: Alternatives, Challenges and Recommendations Juan J. Sánchez Automotive Linux Summit 2015, Tokyo Myself, Igalia and Webkit/Chromium Co-founder of Igalia Open source consultancy founded in 2001 Igalia is Top 5 contributor to upstream WebKit/Chromium Working with many industry actors: automotive, tablets, phones, smart tv, set-top boxes, IVI and home automation Building a Browser for Automotive Juan J. Sánchez Outline 1 A browser for automotive: requirements and alternatives 2 WebKit and Chromium, a historical perspective 3 Selecting between WebKit and Chromium based alternatives Building a Browser for Automotive Juan J. Sánchez PART 1 A browser for automotive: requirements and alternatives Building a Browser for Automotive Juan J. Sánchez Requirements Different User Experiences UI modifications (flexibility) New ways of interacting: accessibility support Support of specific standards (mostly communication and interfaces) Portability: support of specific hardware boards (performance optimization) Functionality and completeness can be less demanding in some cases (for now) Provide both browser as an application and as a runtime Building a Browser for Automotive Juan J. Sánchez Available alternatives Option 1) Licensing a proprietary solution: might bring a reduced time-to-market but involves a cost per unit and lack of flexibility Option 2) Deriving a new browser from the main open source browser technologies: Firefox (Gecko) Chromium WebKit (Safari and others) Mozilla removed support in their engine for third -

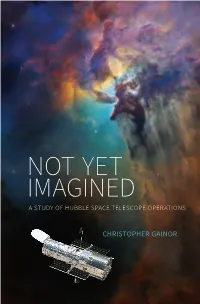

Not Yet Imagined: a Study of Hubble Space Telescope Operations

NOT YET IMAGINED A STUDY OF HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE OPERATIONS CHRISTOPHER GAINOR NOT YET IMAGINED NOT YET IMAGINED A STUDY OF HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE OPERATIONS CHRISTOPHER GAINOR National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Communications NASA History Division Washington, DC 20546 NASA SP-2020-4237 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Gainor, Christopher, author. | United States. NASA History Program Office, publisher. Title: Not Yet Imagined : A study of Hubble Space Telescope Operations / Christopher Gainor. Description: Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Office of Communications, NASA History Division, [2020] | Series: NASA history series ; sp-2020-4237 | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: “Dr. Christopher Gainor’s Not Yet Imagined documents the history of NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope (HST) from launch in 1990 through 2020. This is considered a follow-on book to Robert W. Smith’s The Space Telescope: A Study of NASA, Science, Technology, and Politics, which recorded the development history of HST. Dr. Gainor’s book will be suitable for a general audience, while also being scholarly. Highly visible interactions among the general public, astronomers, engineers, govern- ment officials, and members of Congress about HST’s servicing missions by Space Shuttle crews is a central theme of this history book. Beyond the glare of public attention, the evolution of HST becoming a model of supranational cooperation amongst scientists is a second central theme. Third, the decision-making behind the changes in Hubble’s instrument packages on servicing missions is chronicled, along with HST’s contributions to our knowledge about our solar system, our galaxy, and our universe.