CORIOLIS VOLUME 10, NUMBER 1, 2020 1 the Serendipitous Saga Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

321 M. Naum and J.M. Nordin (Eds.), Scandinavian Colonialism and the Rise of Modernity: Small Time Agents in a Global Arena

Index A Swedish iron Almenn landskipunarfræði , 40 Board of Mines , 55 Amina revolt global integration , 55 Aquambo nation , 266 market economy , 54 ethnic networks , 264 metal trades , 54 French soldiers , 264 Moravian mission , 265 rebels , 264 B 1733 revolt , 265 Bankhus site , 288–289 Slave Coast , 265 Berckentin Palace , 9 St. Thomas , 263 Brevis Commentarius de Islandia , 39 Atlantic economy Gammelbo to Calabar African traders , 59 C European slave trade and New World Charlotte Amalie port slavery , 60 archaeological exploration , 280 Gammelbo forgemen , 58 Bankhus site , 288–289 slave ships , 59 Caribbean market , 276 voyage iron , 58 cast iron , 279 ironworks Danish trade , 275 Bergslagen region , 55 historical documents , 276 bergsmän , 56 housing compounds, Government Hill , 279 bruks , 56 Magens House site Dannemora mine , 57 ceramics , 284 Dutch and British consumers , 58 Crown House , 283 osmund iron , 56 Danish fl uted lace porcelain , 284 pig iron , 56 excavated material remains , 285 Leufsta to Birmingham’s steel furnaces high-cost goods , 286 British manufacturers market , 64 ironwork , 286 common iron , 61 Moravian ware , 284 international market , 63 terraces , 285 iron quality , 64 urban garden , 287 järnboden storehouse , 63 nineteenth-century gates , 281 Öregrund Iron , 62 spatial analysis Walloon forging technique , 61 Blackbeard’s Castle , 282 Swedish economy , 64–66 bone button blanks , 283 M. Naum and J.M. Nordin (eds.), Scandinavian Colonialism and the Rise of Modernity: 321 Small Time Agents in a Global Arena, Contributions To Global Historical Archaeology 37, DOI 10.1007/978-1-4614-6202-6, © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 322 Index Charlotte Amalie port (cont.) Greenland , 107–108 cultural meaning and intentions , 281 illegal trade interisland trade of goods and alcoholic beverages , 109 wares , 282 British faience plate , 109 social relations , 281 buy and discard practice , 110 transhipment/redistribution centre , 283 Disko Bay , 108 St. -

Spring 2020 Virtual Commencement Exercises Click Here to View Ceremonies

SOUTHERN NEW HAMPSHIRE UNIVERSITY SPRING 2020 VIRTUAL COMMENCEMENT EXERCISES CLICK HERE TO VIEW CEREMONIES SATURDAY, MAY 8, 12 PM ET 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONFERRAL GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE DEGREES ........................................ 1 SNHU Honor Societies Honor Society Listing .................................................................................................. 3 Presentation of Degree Candidates COLLEGE FOR AMERICA .............................................................................................. 6 BUSINESS PROGRAMS ................................................................................................ 15 COUNSELING PROGRAMS ........................................................................................... 57 EDUCATION PROGRAMS ............................................................................................ 59 HEALTHCARE PROGRAMS .......................................................................................... 62 LIBERAL ARTS PROGRAMS .........................................................................................70 NURSING PROGRAMS .................................................................................................92 SOCIAL SCIENCE PROGRAMS ..................................................................................... 99 SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, ENGINEERING AND MATH (STEM) PROGRAMS ................... 119 Post-Ceremony WELCOME FROM THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION ............................................................ 131 CONFERRAL OF GRADUATE -

Emancipation in St. Croix; Its Antecedents and Immediate Aftermath

N. Hall The victor vanquished: emancipation in St. Croix; its antecedents and immediate aftermath In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 58 (1984), no: 1/2, Leiden, 3-36 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl N. A. T. HALL THE VICTOR VANQUISHED EMANCIPATION IN ST. CROIXJ ITS ANTECEDENTS AND IMMEDIATE AFTERMATH INTRODUCTION The slave uprising of 2-3 July 1848 in St. Croix, Danish West Indies, belongs to that splendidly isolated category of Caribbean slave revolts which succeeded if, that is, one defines success in the narrow sense of the legal termination of servitude. The sequence of events can be briefly rehearsed. On the night of Sunday 2 July, signal fires were lit on the estates of western St. Croix, estate bells began to ring and conch shells blown, and by Monday morning, 3 July, some 8000 slaves had converged in front of Frederiksted fort demanding their freedom. In the early hours of Monday morning, the governor general Peter von Scholten, who had only hours before returned from a visit to neighbouring St. Thomas, sum- moned a meeting of his senior advisers in Christiansted (Bass End), the island's capital. Among them was Lt. Capt. Irminger, commander of the Danish West Indian naval station, who urged the use of force, including bombardment from the sea to disperse the insurgents, and the deployment of a detachment of soldiers and marines from his frigate (f)rnen. Von Scholten kept his own counsels. No troops were despatched along the arterial Centreline road and, although he gave Irminger permission to sail around the coast to beleaguered Frederiksted (West End), he went overland himself and arrived in town sometime around 4 p.m. -

Personnages Marins Historiques Importants

PERSONNAGES MARINS HISTORIQUES IMPORTANTS Années Pays Nom Vie Commentaires d'activité d'origine Nicholas Alvel Début 1603 Angleterre Actif dans la mer Ionienne. XVIIe siècle Pedro Menéndez de 1519-1574 1565 Espagne Amiral espagnol et chasseur de pirates, de Avilés est connu Avilés pour la destruction de l'établissement français de Fort Caroline en 1565. Samuel Axe Début 1629-1645 Angleterre Corsaire anglais au service des Hollandais, Axe a servi les XVIIe siècle Anglais pendant la révolte des gueux contre les Habsbourgs. Sir Andrew Barton 1466-1511 Jusqu'en Écosse Bien que servant sous une lettre de marque écossaise, il est 1511 souvent considéré comme un pirate par les Anglais et les Portugais. Abraham Blauvelt Mort en 1663 1640-1663 Pays-Bas Un des derniers corsaires hollandais du milieu du XVIIe siècle, Blauvelt a cartographié une grande partie de l'Amérique du Sud. Nathaniel Butler Né en 1578 1639 Angleterre Malgré une infructueuse carrière de corsaire, Butler devint gouverneur colonial des Bermudes. Jan de Bouff Début 1602 Pays-Bas Corsaire dunkerquois au service des Habsbourgs durant la XVIIe siècle révolte des gueux. John Callis (Calles) 1558-1587? 1574-1587 Angleterre Pirate gallois actif la long des côtes Sud du Pays de Galles. Hendrik (Enrique) 1581-1643 1600, Pays-Bas Corsaire qui combattit les Habsbourgs durant la révolte des Brower 1643 gueux, il captura la ville de Castro au Chili et l'a conserva pendant deux mois[3]. Thomas Cavendish 1560-1592 1587-1592 Angleterre Pirate ayant attaqué de nombreuses villes et navires espagnols du Nouveau Monde[4],[5],[6],[7],[8]. -

"EWJ AFRICA" ERICA" HI CURRICU UM GUIDE Grades 9 T

THE "EWJ AFRICA" ERICA" HI CURRICU UM GUIDE Grades 9 t Larry fl. Greene Lenworth Gunther Trenton new Jersey Historical Commission. Department of State CONTENTS Foreword 5 About the Authors 7 Preface 9 How to Use This Guide 11 Acknowledgments 13 Unit 1 African Beginnings 15 Unit 2 Africa, Europe, and the Rise of Afro-America, 1441-1619 31 Unit 3 African American Slavery in the Colonial Era, 1619-1775 50 Unit 4 Blacks in the Revolutionary Era, 1776-1789 61 Unit 5 Slavery and Abolition in Post-Revolutionary and Antebellum America, 1790-1860 72 Unit 6 African Americans and the Civil War, 1861-1865 88 Unit 7 The Reconstruction Era, 1865-1877 97 Unit 8 The Rise ofJim Crow and The Nadir, 1878-1915 106 Unit 9 World War I and the Great Migration, 1915-1920 121 Unit 10 The Decade of the Twenties: From the Great Migration to the Great Depression 132 Unit 11 The 1930s: The Great Depression 142 Unit 12 World War II: The Struggle for Democracy at Home and Abroad, 1940-1945 151 Unit 13 The Immediate Postwar Years, 1945-1953 163 Unit 14 The Civil Rights and Black Power Era: Gains and Losses, 1954-1970 173 Unit 15 Beyond Civil Rights, 1970-1994 186 3 DEDICATED TO Vallie and Rolph Greene and Freddy FOREWORD Because the New Jersey African American History along with the decade's considerable social agitation Curriculum Guide: Grades 9 to 12 is a unique educa and the consciousness-raising experiences that it en tional resource, most persons interested in teaching gendered, encouraged other groups to decry their African American history to New Jersey high school marginal place in American history and to clamor, students will welcome its appearance. -

The Transatlantic Slave Trade

1 2 3 4 The Transatlantic Slave Trade 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 [First Page] 12 13 [-1], (1) 14 15 Lines: 0 to 9 16 17 ——— 18 * 455.0pt PgVar ——— 19 Normal Page 20 * PgEnds: PageBreak 21 22 23 [-1], (1) 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 BOB — University of Nebraska Press / Page i / / The Transatlantic Slave Trade / James A. Rawley 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 [-2], (2) 14 15 Lines: 9 to 10 16 17 ——— 18 0.0pt PgVar ——— 19 Normal Page 20 PgEnds: T X 21 E 22 23 [-2], (2) 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 BOB — University of Nebraska Press / Page ii / / The Transatlantic Slave Trade / James A. Rawley 1 2 3 4 The Transatlantic 5 6 7 8 Slave Trade 9 10 11 A History, revised edition 12 13 [-3], (3) 14 15 Lines: 10 to 32 16 17 ——— 18 0.0pt PgVar ——— 19 James A. Rawley Normal Page 20 * PgEnds: PageBreak 21 with Stephen D. Behrendt 22 23 [-3], (3) 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 university of nebraska press 39 lincoln and london BOB — University of Nebraska Press / Page iii / / The Transatlantic Slave Trade / James A. Rawley 1 © 1981, 2005 by James A. Rawley 2 All rights reserved 3 Manufactured in the United States of America 4 ⅜ϱ 5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data 6 Rawley, James A. -

Timeline of the Virgin Islands with Emphasis on Linguistics, Compiled by Sara Smollett, 2011

Timeline of the Virgin Islands with emphasis on linguistics, compiled by Sara Smollett, 2011. Sources: Hall, Slave Society in the Danish West Indies, 1992; Dookhan, A History of the Virgin Islands of the United States, 1994; Westergaard, The Danish West Indies under Company Rule (1671 { 1754), 1917; Oldendorp, Historie der caribischen Inseln Sanct Thomas, 1777; Highfield, The French Dialect of St Thomas, 1979; Boyer, America's Virgin Islands, 2010; de Albuquerque and McElroy in Glazier, Caribbean Ethnicity Revisited, 1985; http://en.wikipedia.org/; http://www.waterislandhistory.com; http://www.northamericanforts.com/; US census data I've used modern names throughout for consistency. However, at various previous points in time: St Croix was Santa Cruz, Christiansted was Bassin; Charlotte Amalie was Taphus; Vieques was Crab Island; St Kitts was St Christopher. Pre-Columbus .... first Ciboneys, then later Tainos and Island Caribs settle the Virgin Islands Early European exploration 1471 Portuguese arrive on the Gold Coast of Africa 1493 Columbus sails past and names the islands, likely lands at Salt River on St Croix and meets natives 1494 Spain and Portugal define the Line of Demarcation 1502 African slaves are first brought to Hispanola 1508 Ponce de Le´onsettles Puerto Rico 1553 English arrive on the Gold Coast of Africa 1585 Sir Francis Drake likely anchors at Virgin Gorda 1588 Defeat of the Spanish Armada 1593 Dutch arrive on the Gold Coast of Africa 1607 John Smith stopped at St Thomas on his way to Jamestown, Virginia Pre-Danish settlement -

Variation and Change in Virgin Islands Dutch Creole Tense, Modality and Aspect

VARIATION AND CHANGE IN VIRGIN ISLANDS DUTCH CREOLE TENSE, MODALITY AND ASPECT Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration: Annaberg sugar mill ruins, St. John, US Virgin Islands. Picture taken by flickr user Navin75. Original in full color. Reproduced and adapted within the freedoms granted by the license terms (CC BY-SA 2.0) applied by the licensor. ISBN: 978-94-6093-235-9 NUR 616 Copyright © 2017: Robbert van Sluijs. All rights reserved. Variation and change in Virgin Islands Dutch Creole Tense, Modality and Aspect Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. dr. J.H.J.M. van Krieken, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 11 mei 2017 om 10.30 uur precies door Robbert van Sluijs geboren op 23 januari 1987 te Heerlen Promotor: Prof. dr. P.C. Muysken Copromotor: Dr. M.C. van den Berg (UU) Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. R.W.N.M. van Hout Dr. A. Bruyn (Instituut voor de Nederlandse Taal, Den Haag) Prof. dr. F.L.M.P. Hinskens (VU) Prof. dr. S. Kouwenberg (University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica) Prof. dr. C.H.M. Versteegh Part of the research reported in this dissertation was funded by the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen (KNAW). i TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v ABBREVIATIONS ix 1. VARIATION IN VIRGIN ISLANDS DUTCH CREOLE: TENSE-ASPECT- MODALITY 1 1.1. -

Jewish Pirates

Jewish Pirates by Long John Silverman The Wikipedia page on piracy gives you a lot of clues, if you know what to look for. One of the biggest clues are these two sentences, conspicuously stuck right next to each other: The earliest documented instances of piracy are the exploits of the Sea Peoples who threatened the ships sailing in the Aegean and Mediterranean waters in the 14th century BC. In classical antiquity, the Phoenicians, Illyrians and Tyrrhenians were known as pirates. Wikipedia is all but admitting what our historians do gymnastics to avoid admitting: Sea Peoples = Phoenicians. Just as we suspected. We can ignore “Illyrians” and “Tyrrhenians,” which are just poorly devised synonyms for Phoenicians. Wiki tells us Tyrrhenian is simply what the Greeks called a non-Greek person, but then it states that Lydia was “the original home of the Tyrrhenians,” which belies the fact that they were known by the Greeks as a specific people from a specific place, not just any old non-Greek person. Wiki then cleverly tells us “Spard” or “Sard” was a name “closely connected” to the name Tyrrhenian, since the Tyrrhenian city of Lydia was called Sardis by the Greeks. (By the way, coins were first invented in Lydia – so they were some of the earliest banksters). But that itself is misleading, since the Lydians also called themselves Śfard. Nowhere is the obvious suggested – that Spard/Śfard looks a lot like Sephardi, as in Sephardi Jews. These refer to Jews from the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal), the word coming from Sepharad, a place mentioned in the book of Obadiah whose location is lost to history. -

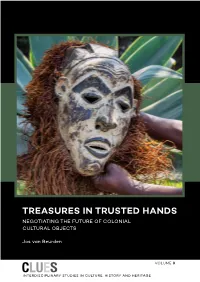

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. -

Postcolonising Danish Foreign Policy Activism in the Global South: Cases of Ghana, India and the Us Virgin

Nikita Pliusnin POSTCOLONISING DANISH FOREIGN POLICY ACTIVISM IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH: CASES OF GHANA, INDIA AND THE US VIRGIN ISLANDS Faculty of Management and Business Master‟s Thesis April 2021 ABSTRACT Nikita Pliusnin: Postcolonising Danish Foreign Policy Activism in the Global South: Cases of Ghana, India and the US Virgin Islands Master‟s Thesis Tampere University Master‟s Programme in Leadership for Change, European and Global Politics, CBIR April 2021 There is a growing corpus of academic literature, which is aimed to analyse Danish activism as a new trend of the kingdom‟s foreign policy. Different approaches, both positivist and post-positivist ones, study specific features of activism, as well the reasons of why this kind of foreign policy has emerged in post- Cold War Denmark. Nevertheless, little has been said on the role of Danish colonial past in the formation of strategies and political courses towards other states and regions. The heterogeneous character of Danish colonialism has also been overlooked by scholars: while Greenland, Iceland and the Faroe Islands are thoroughly examined in Danish postcolonial studies, so-called „tropical colonies‟ (the Danish West Indies, the Danish Gold Coast and Danish India) are almost „forgotten‟. The aim of the thesis is to investigate how the Danish colonial past (or rather the interpretations of the past by the Danish authorities) in the Global South influences modern Danish foreign policy in Ghana, India and US Virgin Islands (the USVI) (on the present-day territories of which Danish colonies were once situated). An authored theoretical and methodological framework of the research is a compilation of discourse theory by Laclau and Mouffe (1985) and several approaches within postcolonialism, including Orientalism by Said (1978) and hybridity theory by Bhabha (1994). -

Daniel Anyim “WE SOLD SLAVES TOO”

Daniel Anyim “WE SOLD SLAVES TOO”: THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ANOMABO AND FORT WILLIAM IN PUBLIC NARRATIVES SURROUNDING THE ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE. MA Thesis in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Central European University Budapest CEU eTD Collection June 2020 “WE SOLD SLAVES TOO”: THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ANOMABO AND FORT WILLIAM IN PUBLIC NARRATIVES SURROUNDING THE ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE. by Daniel Anyim (Ghana) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ CEU eTD Collection Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest June 2020 “WE SOLD SLAVES TOO”: THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ANOMABO AND FORT WILLIAM IN PUBLIC NARRATIVES SURROUNDING THE ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE. by Daniel Anyim (Ghana) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest June 2020 “WE SOLD