Medvick 2021 Phd Dissertation 1St Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Response of the Japanese-Brazilian Community of São Paulo to the Triple Disaster of 2011

Disaster, Donations, and Diaspora: The Response of the Japanese-Brazilian Community of São Paulo to the Triple Disaster of 2011 Peter Bernardi The triple disaster or 3/11, the devastating combination of earthquake, tsunami and the meltdown of reactors at the nuclear power plant Fukushima Daiichi that happened in Japan on March 11, 2011, was a globally reported catastrophe. The Japanese diasporic communities especially demonstrated their willingness to help, organize campaigns and send donations. While a commitment to restor- ing and relating to the homeland in some way confirms William Safran’s (1991: 84) initial criteria for diasporas, the study of the Japanese diasporic communi- ties’ response to 3/11 also offers insights into these communities and their status. This paper offers an analysis of the impact of 3/11 drawn from the reaction of the Japanese-Brazilian diaspora in São Paulo. Although initiatives to help Japan were started throughout Brazil, São Paulo hosts the largest and most influential nikkei community that organized the biggest campaigns. Furthermore, the ar- ticle is my attempt to relate observed connections between disaster, donations and diaspora. I had originally scheduled fieldwork on Japanese immigration for March 2011, but after arriving in Brazil on March 12, reactions to the catas- trophes of 3/11 were a constant topic in many encounters and overlapped my intended research on the nikkei community of São Paulo. Donations played an important role, and in this article I argue that help (especially financial) after 3/11 was not only about Japan but also the self-perception of the nikkei community in São Paulo. -

Rosana Barbosa Nunes

PORTUGUESE MIGRATION TO RIO DE JANEIRO, Rosana Barbosa Nunes A ~hesissubmitted in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of History University of Toronto. Q Rosana Barbosa Nunes, 1998. National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Wellington OttawaON K1AON4 OttawaON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Librâry of Canada to ~ibliothequenationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriiute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format élecîronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Em Mem6ria da Minha Sogra, Martinha dos Anjos Rosa Nunes. Para os Meus Filhos Gabriel and Daniel. Acknowledgements mer the years, my journey towards this dissertation was made possible by the support of many individuals: Firstly, 1 would like to thank my parents, SebastiZo and Camelina Barbosa for continually encouraging me, since the first years of my B.A. in Rio de Janeiro. 1 would also like to thank my husband Fernando, for his editing of each subsequent draft of this thesis, as well as for his devoted companionship during this process. -

Bahiam Defense Draft

EXPULSIONS AND RECEPTIONS: PALESTINIAN IRAQ WAR REFUGEES IN THE BRAZILIAN NATION-STATE by BAHIA MICHELINE MUNEM A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Women’s and Gender Studies Written under the direction of Ana Y. Ramos-Zayas And approved by _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Expulsions and Receptions: Palestinian Iraq War Refugees in the Brazilian Nation-state By BAHIA MICHELINE MUNEM Dissertation Director: Ana Y. Ramos-Zayas This dissertation examines the resettlement of a group of Palestinian Iraq War refugees in Brazil. In 2007, Latin America's largest democracy and self-proclaimed racial democracy made what it claimed was a humanitarian overture by resettling 108 Palestinian refugees displaced from Baghdad as a result of the Iraq War. The majority of them had escaped from Baghdad in 2003 and had been living for nearly five years in a makeshift refugee camp on the border of Jordan and Iraq. Utilizing a multi-method approach, this work examines how Brazil, with its long history of Arab migration, incorporates this specific re-diasporized group into the folds of its much-touted racial democracy, an important arm of Brazilian exceptionalism. In order to address the particularity of Palestinian refugees, and while considering pluralism discourses and other important socio-political dynamics, I engage and extend Edward Said’s framework of Orientalism by analyzing its machinations in Brazil. To closely assess the particularity of the resettled Palestinian refugees (but also Arabs more generally), I consider how already stereotyped Brazilians construct Palestinians in Brazil through an Orientalist lens. -

RETRATOS DA MÚSICA BRASILEIRA 14 Anos No Palco Do Programa Sr.Brasil Da TV Cultura FOTOGRAFIAS: PIERRE YVES REFALO TEXTOS: KATIA SANSON SUMÁRIO

RETRATOS DA MÚSICA BRASILEIRA 14 anos no palco do programa Sr.Brasil da TV Cultura FOTOGRAFIAS: PIERRE YVES REFALO TEXTOS: KATIA SANSON SUMÁRIO PREFÁCIO 5 JAMELÃO 37 NEY MATOGROSSO 63 MARQUINHO MENDONÇA 89 APRESENTAÇÃO 7 PEDRO MIRANDA 37 PAULINHO PEDRA AZUL 64 ANTONIO NÓBREGA 91 ARRIGO BARNABÉ 9 BILLY BLANCO 38 DIANA PEQUENO 64 GENÉSIO TOCANTINS 91 HAMILTON DE HOLANDA 10 LUIZ VIEIRA 39 CHAMBINHO 65 FREI CHICO 92 HERALDO DO MONTE 11 WAGNER TISO 41 LUCY ALVES 65 RUBINHO DO VALE 93 RAUL DE SOUZA 13 LÔ BORGES 41 LEILA PINHEIRO 66 CIDA MOREIRA 94 PAULO MOURA 14 FÁTIMA GUEDES 42 MARCOS SACRAMENTO 67 NANA CAYMMI 95 PAULINHO DA VIOLA 15 LULA BARBOSA 42 CLAUDETTE SOARES 68 PERY RIBEIRO 96 MARIANA BALTAR 16 LUIZ MELODIA 43 JAIR RODRIGUES 69 EMÍLIO SANTIAGO 96 DAÍRA 16 SEBASTIÃO TAPAJÓS 44 MILTON NASCIMENTO 71 DORI CAYMMI 98 CHICO CÉSAR 17 BADI ASSAD 45 CARLINHOS VERGUEIRO 72 PAULO CÉSAR PINHEIRO 98 ZÉ RENATO 18 MARCEL POWELL 46 TOQUINHO 73 HERMÍNIO B. DE CARVALHO 99 CLAUDIO NUCCI 19 YAMANDU COSTA 47 ALMIR SATER 74 ÁUREA MARTINS 99 SAULO LARANJEIRA 20 RENATO BRAZ 48 RENATO TEIXEIRA 75 MILTINHO EDILBERTO 100 GERMANO MATHIAS 21 MÔNICA SALMASO 49 PAIXÃO CÔRTES 76 PAULO FREIRE 101 PAULO BELLINATI 22 CONSUELO DE PAULA 50 LUIZ CARLOS BORGES 76 ARTHUR NESTROVSKI 102 TONINHO FERRAGUTTI 23 DÉRCIO MARQUES 51 RENATO BORGHETTI 78 JÚLIO MEDAGLIA 103 CHICO MARANHÃO 24 SUZANA SALLES 52 TANGOS &TRAGEDIAS 78 SANTANNA, O Cantador 104 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) PAPETE 25 NÁ OZETTI 52 ROBSON MIGUEL 79 FAGNER 105 (Câmara Brasileira do Livro, SP, Brasil) ANASTÁCIA 26 ELZA SOARES 53 JORGE MAUTNER 80 OSWALDO MONTENEGRO 106 Refalo, Pierre Yves Retratos da música brasileira : 14 anos no palco AMELINHA 26 DELCIO CARVALHO 54 RICARDO HERZ 80 VÂNIA BASTOS 106 do programa Sr. -

As Duas Vidas De Joaquim Nabuco O Reformador E O Diplomata the Two Lifes of Joaquim Nabuco the Reformer and the Diplomat Las

AS DUAS VIDAS DE JOAQUIM NABUCO: O REFORMADOR E O DIPLOMATA THE TWO LIFES OF JOAQUIM NABUCO: THE REFORMER AND THE DIPLOMAT LAS DOS VIDAS DE JOAQUIM NABUCO: EL REFORMADOR Y EL DIPLOMÁTICO MINISTÉRIO DAS RELAÇÕES EXTERIORES Ministro de Estado Embaixador Celso Amorim Secretário-Geral Embaixador Antonio de Aguiar Patriota FUNDAÇÃO A LEXANDRE DE GUSMÃO Presidente Embaixador Jeronimo Moscardo Instituto de Pesquisa de Relações Internacionais Diretor Embaixador Carlos Henrique Cardim A Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão, instituída em 1971, é uma fundação pública vinculada ao Ministério das Relações Exteriores e tem a finalidade de levar à sociedade civil informações sobre a realidade internacional e sobre aspectos da pauta diplomática brasileira. Sua missão é promover a sensibilização da opinião pública nacional para os temas de relações internacionais e para a política externa brasileira. Ministério das Relações Exteriores Esplanada dos Ministérios, Bloco H Anexo II, Térreo, Sala 1 70170-900 Brasília, DF Telefones: (61) 3411-6033/6034/6847 Fax: (61) 3411-9125 Site: www.funag.gov.br As duas vidas de Joaquim Nabuco: O Reformador e o Diplomata The two lifes of Joaquim Nabuco: The Reformer and the Diplomat Las dos vidas de Joaquim Nabuco: El Reformador y el Diplomático Brasília, 2010 Direitos de publicação reservados à Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão Ministério das Relações Exteriores Esplanada dos Ministérios, Bloco H Anexo II, Térreo 70170-900 Brasília DF Telefones: (61) 3411-6033/6034 Fax: (61) 3411-9125 Site: www.funag.gov.br E-mail: [email protected] Capa: Fotografia de Cristiano Junior, "Escravo de ganho" 8,5 x 5 cm - 1865 Equipe Técnica: Maria Marta Cezar Lopes Henrique da Silveira Sardinha Pinto Filho André Yuji Pinheiro Uema Cíntia Rejane Sousa Araújo Gonçalves Erika Silva Nascimento Juliana Corrêa de Freitas Fernanda Leal Wanderley Programação Visual e Diagramação: Juliana Orem Tradução e Revisão: Fátima Ganin - Português e Espanhol Paulo Kol - Inglês Impresso no Brasil 2010 D866 As duas vidas de Joaquim Nabuco: o reformador e o diplomata. -

Curriculum Vitae Beatriz Padilla May, 2020

Curriculum Vitae Beatriz Padilla May, 2020 Table of Contents PERSONAL INFORMATION .............................................................................................................................. 3 EDUCATION ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS ............................................................................................................................ 5 RESEARCH DEVELOPMENT & ACTIVITIES ................................................................................................ 6 RESEARCH PROJECTS & EXPERIENCE ..................................................................................................................... 6 PARTICIPATION IN OTHER FUNDED RESEARCH PROJECTS (team member) ........................................... 8 EUROPEAN & INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH NETWORKS .................................................................................. 9 SCIENTIFIC PRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 9 PUBLICATIONS ............................................................................................................................................................... 9 PAPERS PRESENTED ................................................................................................................................................... 25 ORGANIZATION OF CONFERENCES, -

The 1959 Educators' Manifesto Revisited

POLÍTICAS PÚBLICAS, AVALIAÇÃO E GESTÃO PUBLIC POLICIES, EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT POLÍTICAS PÚBLICAS, EVALUACIÓN Y GESTIÓN POLITIQUES PUBLIQUES, ÉVALUATION ET GESTION https://doi.org/10.1590/198053147278 O MANIFESTO DOS EDUCADORES DE 1959 REVISITADO: EVENTO, NARRATIVAS E DISCURSOS Bruno Bontempi Jr.I I Universidade de São Paulo (USP), São Paulo, Brasil; [email protected] Resumo Trata-se de análise histórica do manifesto de educadores “Mais uma vez convocados: manifesto ao 1 povo e ao governo” (1959), divulgado em resposta à irrupção de um substitutivo ao projeto de Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação. Examina os alicerces de sua memória, interrogando as razões e os efeitos da predominante explicação por meio de suas relações com o Manifesto dos Pioneiros e a Campanha em Defesa da Escola Pública. Reconstrói eventos, agentes e significados, compreendendo-os como ação coletiva e coordenada de intelectuais para fins políticos determinados. Conclui-se realçando o manifesto em sua especificidade e historicidade, aparando equívocos historiográficos resultantes de repetições sem lastro e abordagens que produziram lacunas em sua compreensão como evento singular. INTELECTUAIS • DOCUMENTOS • IMPRENSA • HISTÓRIA DA EDUCAÇÃO THE 1959 EDUCATORS’ MANIFESTO REVISITED: EVENT, NARRATIVES AND DISCOURSES Abstract This article presents a historical analysis of the 1959 educators’ manifesto “Mais uma vez convocados: manifesto ao povo e ao governo” [Summoned once again: manifesto to the people and to the government], made public in response to the proposal of an amendment to the Draft Law of Bases and Guidelines of Education. The text examines the foundations of the manifesto’s memory, investigating the reasons and effects of its predominant explanation through its relations to the Pioneers Manifesto and to the Campaign in Defense of Public School. -

4-08 M-Blick

Ausgabe 04-2008 Michel Blick Verteiler: Hamburg Tourismus GmbH (Landungsbrücken/Hauptbahnhof) Handelskammer Wirtschaftsverbände Hafen Klub Hamburg Museen u. Kunststätten Stadtmodell u. Senat Polizeiwache 14 Hotels u. Restaurants Werbeträger Serie:Serie: RundgangRundgang durchdurch Watt´n Ranger – Kinderprojekt Karneval in Hamburg Diedie NeustadtHamburger und Neustadt auf der Insel Neuwerk 7. Michelwiesenfest Hafenregionund Hafenregion – Teil - 4Teil 2 und Maracatu - afro-brasilianische Musik- und Tanzgruppen IHR PERSÖNLICHES EXEMPLAR ZUM MITNEHMEN! Service Erste Anlaufstellen NOTRUFE Polizei 110 Feuerwehr 112 Rettungsdienst 112 Krankenwagen 192 19 Polizeikommissariat 14 RECHT Caffamacherreihe 4, 20355 Hamburg 42 86-5 14 10 Öffentliche Rechtsauskunft und Vergleichsstelle (ÖRA) Aids-Seelsorge 280 44 62 Leiterin: Monika Hartges, 4 28 43 – 30 71 Aids-Hilfe 194 11 Holstenwall 6, 20355 Hamburg 428 43 – 30 71 Anonyme Alkoholiker 271 33 53 Seniorenberatung Anwaltlicher Notdienst 0180-524 63 73 ist eine Beratungsstelle mit dem größten Überblick über Ärztlicher Notdienst 22 80 22 Angebote für Seniorinnen und Senioren. Hafen Apotheke (Int. Rezepte) 375 18 381 Ansprechpartner für den Bezirk Neustadt: Herr Thomas Gift-Informations-Zentrale05 51-192 40 Sprechzeit: Montag 9-12 Uhr und 13-15.30 Uhr Hamburger Kinderschutzzentrum 491 00 07 Kurt-Schumacher-Allee 4, 20097 Hamburg 428 54-45 57 Kindersorgentelefon 0800-111 03 33 Kinder- und Jugendnotdienst 42 84 90 BEZIRKSSENIORENBEIRAT Notrufnummer der Banken- und Erreichbar über das Bezirksamt Hamburg-Mitte 428 54-23 03 Sparkassen EC-Karten, Bankkunden CHRISTL. KIRCHEN – GEMEINSCHAFTEN – AKADEMIEN und Sparkarten (keine Schecks) 069-74 09 87 oder Ev.-luth. Kirche 01805-02 10 21 St: Michaelis, Englische Planke 1a, 20459 Hamburg 376 78-0 Visa- und Mastercard 069-79 33 19 10 American Express 069-97 97 10 00 Ev.-luth. -

Brazilian/American Trio São Paulo Underground Expands Psycho-Tropicalia Into New Dimensions on Cantos Invisíveis, a Global Tapestry That Transcends Place & Time

Bio information: SÃO PAULO UNDERGROUND Title: CANTOS INVISÍVEIS (Cuneiform Rune 423) Format: CD / DIGITAL Cuneiform Promotion Dept: (301) 589-8894 / Fax (301) 589-1819 Press and world radio: [email protected] | North American and world radio: [email protected] www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / TROPICALIA / ELECTRONIC / WORLD / PSYCHEDELIC / POST-JAZZ RELEASE DATE: OCTOBER 14, 2016 Brazilian/American Trio São Paulo Underground Expands Psycho-Tropicalia into New Dimensions on Cantos Invisíveis, a Global Tapestry that Transcends Place & Time Cantos Invisíveis is a wondrous album, a startling slab of 21st century trans-global music that mesmerizes, exhilarates and transports the listener to surreal dreamlands astride the equator. Never before has the fearless post-jazz, trans-continental trio São Paulo Underground sounded more confident than here on their fifth album and third release for Cuneiform. Weaving together a borderless electro-acoustic tapestry of North and South American, African and Asian, traditional folk and modern jazz, rock and electronica, the trio create music at once intimate and universal. On Cantos Invisíveis, nine tracks celebrate humanity by evoking lost haunts, enduring love, and the sheer delirious joy of making music together. São Paulo Underground fully manifests its expansive vision of a universal global music, one that blurs edges, transcends genres, defies national and temporal borders, and embraces humankind in its myriad physical and spiritual dimensions. Featuring three multi-instrumentalists, São Paulo Underground is the creation of Chicago-reared polymath Rob Mazurek (cornet, Mellotron, modular synthesizer, Moog Paraphonic, OP-1, percussion and voice) and two Brazilian masters of modern psycho- Tropicalia -- Mauricio Takara (drums, cavaquinho, electronics, Moog Werkstatt, percussion and voice) and Guilherme Granado (keyboards, synthesizers, sampler, percussion and voice). -

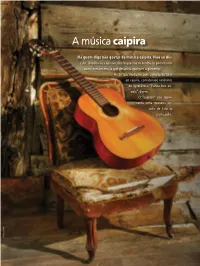

A Música Caipira

A música caipira Há quem diga não gostar da música caipira. Não se dis- cute; respeita-se a opinião, desde que não se estriba no pedantismo ou no preconceito, o que desapeia qualquer argumento. Há os que implicam com o modo de falar do caipira, considerado sinônimo de ignorância. “Faltou-lhes es cola”, dizem. O “caipirês” não repre senta uma maneira er rada de falar o português. Shutterstock "O ‘CAIPIRÊS’ NÃO REPRESENTA UMA MANEIRA ERRADA DE FALAR O PORTUGUÊS. CONSTITUI-SE NUM DIALETO DE RAÍZES ANTIGAS. PORTANTO, O CAIPIRA NÃO FALA ERRADO; ELE FALA UM DIALETO, A música caipira UMA LEGÍTIMA VARIANTE DA LÍNGUA PORTUGUESA." Constitui-se num dialeto de raízes antigas. Portanto, o tes, voltados para o cotidiano do caboclo, para a vida na caipira não fala errado; ele fala um dialeto, uma legíti roça, com suas alegrias e agruras. ma variante da língua portuguesa. Tudo quase terminou A cultura caipira motivou escritores como Guimarães quando o rei de Portugal proibiu o uso da língua geral na Rosa e compositores como Villa-Lobos. Sem ela, teriam Colônia. Nas casas, nas ruas, em qualquer lugar, falava precisado de outra fonte de inspiração para construir -se o tupi-guarani adaptado ao português, ou vice-versa, suas obras monumentais. façanha desenvolvida pelo padre Anchieta. Assim nas Foi inevitável que, com a crescente urbanização, a ceu o nheengatu, a língua brasílica, que se espraiou música sertaneja, dita de raiz, sofresse influências. Há como as ondas do mar de Bertioga e lá foi ela, falada por quem diga que ela foi descaracterizada, mas outros opi todos, desde o litoral de Santa Catarina até o Pará. -

A Freshwater Sponge Misunderstood for a Marine New Genus and Species

Zootaxa 3974 (3): 447–450 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Correspondence ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3974.3.12 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:63265F5C-F70E-48D7-B7C8-7073C5243DA8 An example of the importance of labels and fieldbooks in scientific collections: A freshwater sponge misunderstood for a marine new genus and species ULISSES PINHEIRO1,4, GILBERTO NICACIO1,2 & GUILHERME MURICY3 1Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Centro de Ciências Biológicas, Departamento de Zoologia, Av. Nelson Chaves, s/n Cidade Universitária CEP 50373-970, Recife, PE, Brazil 2Graduate Program in Zoology, Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Av. Perimetral 1901, Terra Firme, Belém, PA, Brazil 3Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional, Departamento de Invertebrados, 20940-040, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil 4Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] The demosponge genus Crelloxea Hechtel, 1983 was created to allocate a single species, Crelloxea spinosa Hechtel, 1983, described based on specimens collected by Jacques Laborel in northeastern Brazil in 1964 and deposited at the Porifera Collection of the Yale Peabody Museum. The genus Crelloxea was originally defined as "Crellidae with dermal and interstitial acanthoxeas and acanthostrongyles, with skeletal oxea and without microscleres or echinators" (Hechtel, 1983). Crelloxea was allocated in the marine sponge family Crellidae (Order Poecilosclerida), which is characterized by a tangential crust of spined ectosomal spicules (oxeas, anisoxeas or styles), a choanosomal plumose skeleton of smooth tornotes, sometimes a basal skeleton of acanthostyles erect on the substrate, microscleres usually arcuate chelae or absent, and surface with areolated pore fields (van Soest, 2002). -

Redalyc.Diagnosis of the Accelerated Soil Erosion in São Paulo State

Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo ISSN: 0100-0683 [email protected] Sociedade Brasileira de Ciência do Solo Brasil de Oliveira Rodrigues Medeiros, Grasiela; Giarolla, Angelica; Sampaio, Gilvan; de Andrade Marinho, Mara Diagnosis of the Accelerated Soil Erosion in São Paulo State (Brazil) by the Soil Lifetime Index Methodology Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, vol. 40, 2016, pp. 1-15 Sociedade Brasileira de Ciência do Solo Viçosa, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=180249980076 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Rev Bras Cienc Solo 2016;40:e0150498 Article Division – Soil Use and Management | Commission – Soil and Water Management and Conservation Diagnosis of the Accelerated Soil Erosion in São Paulo State (Brazil) by the Soil Lifetime Index Methodology Grasiela de Oliveira Rodrigues Medeiros(1)*, Angelica Giarolla(2), Gilvan Sampaio(3) and Mara de Andrade Marinho(4) (1) Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais, Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciência do Sistema Terrestre, Centro de Ciência do Sistema Terrestre, São José dos Campos, São Paulo, Brasil. (2) Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais, Centro de Ciência do Sistema Terrestre, São José dos Campos, São Paulo, Brasil. (3) Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais, Centro de Ciência do Sistema Terrestre, Cachoeira Paulista, São Paulo, Brasil. (4) Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Faculdade de Engenharia Agrícola, Campinas, São Paulo, Brasil. ABSTRACT: The soil is a key component of the Earth System, and is currently under high pressure, due to the increasing global demands for food, energy and fiber.