Edinburgh University Press Michael Mann

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies –

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan Published by Self Improvement Online, Inc. http://www.SelfGrowth.com 20 Arie Drive, Marlboro, NJ 07746 ©Copyright by David Riklan Manufactured in the United States No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Limit of Liability / Disclaimer of Warranty: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. The author shall not be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Spiritual Cinema 8 About SelfGrowth.com 10 Newer Inspirational Movies 11 Ranking Movie Title # 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 13 # 2 Forrest Gump 16 # 3 Field of Dreams 19 # 4 Rudy 22 # 5 Rocky 24 # 6 Chariots of -

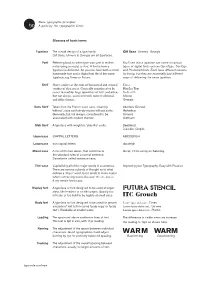

WARM WARM Kerning by Eye for Perfectly Balanced Spacing

Basic typographic principles: A guide by The Typographic Circle Glossary of basic terms Typeface The overall design of a type family Gill Sans Univers Georgia Gill Sans, Univers & Georgia are all typefaces. Font Referring back to when type was cast in molten You’ll see that a typeface can come in various metal using a mould, or font. A font is how a types of digital font; such as OpenType, TrueType typeface is delivered. So you can have both a metal and Postscript fonts. Each have different reasons handmade font and a digital font file of the same for being, but they are essentially just different typeface, e.g Times or Futura. ways of delivering the same typeface. Serif Short strokes at the ends of horizontal and vertical Times strokes of characters. Generally considered to be Hoefler Text easier to read for large quantities of text, and often, Baskerville but not always, associated with more traditional Minion and older themes. Georgia Sans Serif Taken from the French word sans, meaning Akzidenz Grotesk ‘without’, sans serif simply means without serifs. Helvetica Generally, but not always, considered to be Univers associated with modern themes. Gotham Slab Serif A typeface with weightier, ‘slab-like’ serifs. Rockwell Lubalin Graph Uppercase CAPITAL LETTERS ABCDEFGH Lowercase non-capital letters abcdefgh Mixed-case A mix of the two above, that conforms to Great, it’ll be sunny on Saturday. the standard rules of a normal sentence. Sometimes called sentence-case. Title-case Capitalising all of the major words in a sentence. Improving your Typography: Easy with Practice There are various schools of thought as to what defines a ‘major’ word, but it tends to looks neater when connecting words like and, the, to, but, is & my remain lowercase. -

The Defend Trade Secrets Act Whistleblower Immunity Provision: a Legislative History, 1 Bus

The Business, Entrepreneurship & Tax Law Review Volume 1 Article 5 Issue 2 Fall 2017 2017 The efeD nd Trade Secrets Act Whistleblower Immunity Provision: A Legislative History Peter Menell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/betr Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Peter Menell, The Defend Trade Secrets Act Whistleblower Immunity Provision: A Legislative History, 1 Bus. Entrepreneurship & Tax L. Rev. 398 (2017). Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/betr/vol1/iss2/5 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The usineB ss, Entrepreneurship & Tax Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. Menell: DTSA Whistleblower Immunity SYMPOSIUM ARTICLE The Defend Trade Secrets Act Whistleblower Immunity Provision: A Legislative History Peter S. Menell** ABSTRACT The Defend Trade Secrets Act of 2016 (“DTSA”) was the product of a multi-year effort to federalize trade secret protection. In the final stages of drafting the DTSA, Senators Grassley and Leahy introduced an important new element: immunity “for whistleblowers who share confidential infor- mation in the course of reporting suspected illegal activity to law enforce- ment or when filing a lawsuit, provided they do so under seal.” The mean- ing and scope of this provision are of vital importance to enforcing health, safety, civil rights, financial market, consumer, and environmental protec- tions and deterring fraud against the government, shareholders, and the public. This article explains how the whistleblower immunity provision was formulated and offers insights into its proper interpretation. -

Famous Chicagoans Source: Chicago Municipal Library

DePaul Center for Urban Education Chicago Math Connections This project is funded by the Illinois Board of Higher Education through the Dwight D. Eisenhower Professional Development Program. Teaching/Learning Data Bank Useful information to connect math to science and social studies Topic: Famous Chicagoans Source: Chicago Municipal Library Name Profession Nelson Algren author Joan Allen actor Gillian Anderson actor Lorenz Tate actor Kyle actor Ernie Banks, (former Chicago Cub) baseball Jennifer Beals actor Saul Bellow author Jim Belushi actor Marlon Brando actor Gwendolyn Brooks poet Dick Butkus football-Chicago Bear Harry Caray sports announcer Nat "King" Cole singer Da – Brat singer R – Kelly singer Crucial Conflict singers Twista singer Casper singer Suzanne Douglas Editor Carl Thomas singer Billy Corgan musician Cindy Crawford model Joan Cusack actor John Cusack actor Walt Disney animator Mike Ditka football-former Bear's Coach Theodore Dreiser author Roger Ebert film critic Dennis Farina actor Dennis Franz actor F. Gary Gray directory Bob Green sports writer Buddy Guy blues musician Daryl Hannah actor Anne Heche actor Ernest Hemingway author John Hughes director Jesse Jackson activist Helmut Jahn architect Michael Jordan basketball-Chicago Bulls Ray Kroc founder of McDonald's Irv Kupcinet newspaper columnist Ramsey Lewis jazz musician John Mahoney actor John Malkovich actor David Mamet playwright Joe Mantegna actor Marlee Matlin actor Jenny McCarthy TV personality Laurie Metcalf actor Dermot Muroney actor Bill Murray actor Bob Newhart -

Film & Literature

Name_____________________ Date__________________ Film & Literature Mr. Corbo Film & Literature “Underneath their surfaces, all movies, even the most blatantly commercial ones, contain layers of complexity and meaning that can be studied, analyzed and appreciated.” --Richard Barsam, Looking at Movies Curriculum Outline Form and Function: To equip students, by raising their awareness of the development and complexities of the cinema, to read and write about films as trained and informed viewers. From this base, students can progress to a deeper understanding of film and the proper in-depth study of cinema. By the end of this course, you will have a deeper sense of the major components of film form and function and also an understanding of the “language” of film. You will write essays which will discuss and analyze several of the films we will study using accurate vocabulary and language relating to cinematic methods and techniques. Just as an author uses literary devices to convey ideas in a story or novel, filmmakers use specific techniques to present their ideas on screen in the world of the film. Tentative Film List: The Godfather (dir: Francis Ford Coppola); Rushmore (dir: Wes Anderson); Do the Right Thing (dir: Spike Lee); The Dark Knight (dir: Christopher Nolan); Psycho (dir: Alfred Hitchcock); The Graduate (dir: Mike Nichols); Office Space (dir: Mike Judge); Donnie Darko (dir: Richard Kelly); The Hurt Locker (dir: Kathryn Bigelow); The Ice Storm (dir: Ang Lee); Bicycle Thives (dir: Vittorio di Sica); On the Waterfront (dir: Elia Kazan); Traffic (dir: Steven Soderbergh); Batman (dir: Tim Burton); GoodFellas (dir: Martin Scorsese); Mean Girls (dir: Mark Waters); Pulp Fiction (dir: Quentin Tarantino); The Silence of the Lambs (dir: Jonathan Demme); The Third Man (dir: Carol Reed); The Lord of the Rings trilogy (dir: Peter Jackson); The Wizard of Oz (dir: Victor Fleming); Edward Scissorhands (dir: Tim Burton); Raiders of the Lost Ark (dir: Steven Spielberg); Star Wars trilogy (dirs: George Lucas, et. -

Film Essay for "Mccabe & Mrs. Miller"

McCabe & Mrs. Miller By Chelsea Wessels In a 1971 interview, Robert Altman describes the story of “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” as “the most ordinary common western that’s ever been told. It’s eve- ry event, every character, every west- ern you’ve ever seen.”1 And yet, the resulting film is no ordinary western: from its Pacific Northwest setting to characters like “Pudgy” McCabe (played by Warren Beatty), the gun- fighter and gambler turned business- man who isn’t particularly skilled at any of his occupations. In “McCabe & Mrs. Miller,” Altman’s impressionistic style revises western events and char- acters in such a way that the film re- flects on history, industry, and genre from an entirely new perspective. Mrs. Miller (Julie Christie) and saloon owner McCabe (Warren Beatty) swap ideas for striking it rich. Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. The opening of the film sets the tone for this revision: Leonard Cohen sings mournfully as the when a mining company offers to buy him out and camera tracks across a wooded landscape to a lone Mrs. Miller is ultimately a captive to his choices, una- rider, hunched against the misty rain. As the unidenti- ble (and perhaps unwilling) to save McCabe from his fied rider arrives at the settlement of Presbyterian own insecurities and herself from her opium addic- Church (not much more than a few shacks and an tion. The nuances of these characters, and the per- unfinished church), the trees practically suffocate the formances by Beatty and Julie Christie, build greater frame and close off the landscape. -

Bringing Communities Together

BRINGING COMMUNITIES DID YOU A Few Inspiring TOGETHER KNOW Facts CONNECTIONS Film has been bringing communities Today we have a new wave of film Where was the smallest The Terrace Cinema in Tinonee had 22 Films made on or about the Mid North 2001 - Russell Crowe together on the Mid North Coast for festivals and film makers but our history seats. Only recently closed its projector, Coast Oscar, Best Actor, My Beautiful Mind nearly 100 years. From travelling shows of film should not be forgotten. cinema in Australia? curtains, seats and paraphernalia can be like that of Bill Wright to country halls seen at the Tinonee Museum 1977 - The Picture Man 2001 - Russell Crowe to the building of small town cinemas in Golden Globe, Best Actor, My Beautiful Mind the 1930’s and 40’s they have created a 1978 - The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith hub of our social activity. Some classic Where can you still see part The boarding house façade is now incorporated into the Bowraville Museum 2001 - Baz Luhrmann examples still exist (albeit renovated of the set of The Umbrella 1987 - The Umbrella Woman Golden Globe, Best Motion Picture, Moulin and reinvented) while the stories of Woman filmed on the coast Rouge others are still told in our museums and 2003 - Danny Deckchair photographic archives. in 1980’s? 2000 - Russell Crowe 2012 - Thirst Oscar, Best Actor, Gladiator Who was the fittest runner in Whoever had to cycle furiously between the industry? the Tasma and Jetty Cinemas in Coffs 2013 - Adoration 1997 - Geoffrey Rush Harbour in the 1940’s with each reel. -

Bernhardt Hamlet Cast FINAL

IMAGES AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD HERE CAST ANNOUNCED FOR GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE WEST COAST PREMIERE OF “BERNHARDT/HAMLET” FEATURING GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINEE DIANE VENORA AS SARAH BERNHARDT WRITTEN BY THERESA REBECK AND DIRECTED BY SARNA LAPINE ALSO FEATURING NICK BORAINE, ALAN COX, ISAIAH JOHNSON, SHYLA LEFNER, RAYMOND McANALLY, LEVENIX RIDDLE, PAUL DAVID STORY, LUCAS VERBRUGGHE AND GRACE YOO PREVIEWS BEGIN APRIL 7 - OPENING NIGHT IS APRIL 16 LOS ANGELES (February 24, 2020) – Geffen Playhouse today announced the full cast for its West Coast premiere of Bernhardt/Hamlet, written by Theresa Rebeck (Dead Accounts, Seminar) and directed by Sarna Lapine (Sunday in the Park with George). The production features Diane Venora (Bird, Romeo + Juliet) as Sarah Bernhardt. In addition to Venora, the cast features Nick BoraIne (Homeland, Paradise Stop) as Louis, Alan Cox (The Dictator, Young Sherlock Holmes) as Constant Coquelin, Isaiah Johnson (Hamilton, David Makes Man) as Edmond Rostand, Shyla Lefner (Between Two Knees, The Way the Mountain Moved) as Rosamond, Raymond McAnally (Size Matters, Marvelous and the Black Hole) as Raoul, Rosencrantz, and others, Levenix Riddle (The Chi, Carlyle) as Francois, Guildenstern, and others, Paul David Story (The Caine Mutiny Court Martial, Equus) as Maurice, Lucas Verbrugghe (Icebergs, Lazy Eye) as Alphonse Mucha and Grace Yoo (Into The Woods, Root Beer Bandits) as Lysette. It’s 1899, and the legendary Sarah Bernhardt shocks the world by taking on the lead role in Hamlet. While her performance is destined to become one for the ages, Sarah first has to conVince a sea of naysayers that her right to play the part should be based on ability, not gender—a feat as difficult as mastering Shakespeare’s most Verbose tragic hero. -

The Eddie Awards Issue

THE MAGAZINE FOR FILM & TELEVISION EDITORS, ASSISTANTS & POST- PRODUCTION PROFESSIONALS THE EDDIE AWARDS ISSUE IN THIS ISSUE Golden Eddie Honoree GUILLERMO DEL TORO Career Achievement Honorees JERROLD L. LUDWIG, ACE and CRAIG MCKAY, ACE PLUS ALL THE WINNERS... FEATURING DUMBO HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON: THE HIDDEN WORLD AND MUCH MORE! US $8.95 / Canada $8.95 QTR 1 / 2019 / VOL 69 Veteran editor Lisa Zeno Churgin switched to Adobe Premiere Pro CC to cut Why this pro chose to switch e Old Man & the Gun. See how Adobe tools were crucial to her work ow and to Premiere Pro. how integration with other Adobe apps like A er E ects CC helped post-production go o without a hitch. adobe.com/go/stories © 2019 Adobe. All rights reserved. Adobe, the Adobe logo, Adobe Premiere, and A er E ects are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe in the United States and/or other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Veteran editor Lisa Zeno Churgin switched to Adobe Premiere Pro CC to cut Why this pro chose to switch e Old Man & the Gun. See how Adobe tools were crucial to her work ow and to Premiere Pro. how integration with other Adobe apps like A er E ects CC helped post-production go o without a hitch. adobe.com/go/stories © 2019 Adobe. All rights reserved. Adobe, the Adobe logo, Adobe Premiere, and A er E ects are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe in the United States and/or other countries. -

'Perfect Fit': Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity

‘Perfect Fit’: Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity Culture in Fashion Television Helen Warner Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies Submitted July 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. Helen Warner P a g e | 2 ABSTRACT According to the head of the American Costume Designers‟ Guild, Deborah Nadoolman Landis, fashion is emphatically „not costume‟. However, if this is the case, how do we approach costume in a television show like Sex and the City (1998-2004), which we know (via press articles and various other extra-textual materials) to be comprised of designer clothes? Once onscreen, are the clothes in Sex and the City to be interpreted as „costume‟, rather than „fashion‟? To be sure, it is important to tease out precise definitions of key terms, but to position fashion as the antithesis of costume is reductive. Landis‟ claim is based on the assumption that the purpose of costume is to tell a story. She thereby neglects to acknowledge that the audience may read certain costumes as fashion - which exists in a framework of discourses that can be located beyond the text. This is particularly relevant with regard to contemporary US television which, according to press reports, has witnessed an emergence of „fashion programming‟ - fictional programming with a narrative focus on fashion. -

CLE On-Demand

Garden State CLE 2000 Hamilton Ave. Hamilton, N.J. 08619 (609) 584-1924 (609) 895-1899 Fax www.gardenstatecle.Com [email protected] CLE On-Demand View and record the “Secret Words” Print this form and write down all the “secret Words” during the program: (Reporting the words is a required step in getting CLE Credit) Word #1 was: Word #2 was: Word #3 was: Word #4 was: Garden State CLE presents: A Pop Corn CLE: "An Offer You Can't Refuse" Winning Negotiating Techniques as Portrayed in Cinema Lesson Plan Part I - Negotiation as a Process Two Critical Process Issues: 1.) Get your adversary to invest time and effort in the process. The more time, energy & resources invested, the harder it will be for him to walk away. 2.) Build a foundation of consensus by agreeing to as many (usually smaller, insignificant) things as possible early on in the process and leave the highly disputed matters until the end. -------------------------------------------------- The following film is not about war. It is about the process of negotiation. The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) William Holden Alec Guinness Jack Hawkins Sessue Hayakawa Negotiating Issues: Recognition of negotiation as a process; Note mistake of revealing key data early in the process; Zero-sum game; Note the use of all negotiator styles: analytical, practical, amiable, extrovert; The power of time/deadlines – investing and effort time; Late counter offer meets the needs of both parties; Note how emotion & pride clouds judgment & delays resolution. Part II - BATNA The person with the best alternative to a negotiated settlement (BATNA) has the most leverage.