'Flow': Television Nature, Aesthetics and HBO's Luck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies –

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan Published by Self Improvement Online, Inc. http://www.SelfGrowth.com 20 Arie Drive, Marlboro, NJ 07746 ©Copyright by David Riklan Manufactured in the United States No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Limit of Liability / Disclaimer of Warranty: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. The author shall not be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Spiritual Cinema 8 About SelfGrowth.com 10 Newer Inspirational Movies 11 Ranking Movie Title # 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 13 # 2 Forrest Gump 16 # 3 Field of Dreams 19 # 4 Rudy 22 # 5 Rocky 24 # 6 Chariots of -

Famous Chicagoans Source: Chicago Municipal Library

DePaul Center for Urban Education Chicago Math Connections This project is funded by the Illinois Board of Higher Education through the Dwight D. Eisenhower Professional Development Program. Teaching/Learning Data Bank Useful information to connect math to science and social studies Topic: Famous Chicagoans Source: Chicago Municipal Library Name Profession Nelson Algren author Joan Allen actor Gillian Anderson actor Lorenz Tate actor Kyle actor Ernie Banks, (former Chicago Cub) baseball Jennifer Beals actor Saul Bellow author Jim Belushi actor Marlon Brando actor Gwendolyn Brooks poet Dick Butkus football-Chicago Bear Harry Caray sports announcer Nat "King" Cole singer Da – Brat singer R – Kelly singer Crucial Conflict singers Twista singer Casper singer Suzanne Douglas Editor Carl Thomas singer Billy Corgan musician Cindy Crawford model Joan Cusack actor John Cusack actor Walt Disney animator Mike Ditka football-former Bear's Coach Theodore Dreiser author Roger Ebert film critic Dennis Farina actor Dennis Franz actor F. Gary Gray directory Bob Green sports writer Buddy Guy blues musician Daryl Hannah actor Anne Heche actor Ernest Hemingway author John Hughes director Jesse Jackson activist Helmut Jahn architect Michael Jordan basketball-Chicago Bulls Ray Kroc founder of McDonald's Irv Kupcinet newspaper columnist Ramsey Lewis jazz musician John Mahoney actor John Malkovich actor David Mamet playwright Joe Mantegna actor Marlee Matlin actor Jenny McCarthy TV personality Laurie Metcalf actor Dermot Muroney actor Bill Murray actor Bob Newhart -

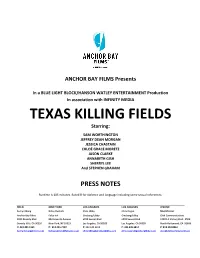

TEXAS KILLING FIELDS Starring

ANCHOR BAY FILMS Presents In a BLUE LIGHT BLOCK/HANSON WATLEY ENTERTAINMENT Production In association with INFINITY MEDIA TEXAS KILLING FIELDS Starring: SAM WORTHINGTON JEFFREY DEAN MORGAN JESSICA CHASTAIN CHLOЁ GRACE MORETZ JASON CLARKE ANNABETH GISH SHERRYL LEE And STEPHEN GRAHAM PRESS NOTES Runtime is 105 minutes. Rated R for violence and language including some sexual references. FIELD NEW YORK LOS ANGELES LOS ANGELES ONLINE Sumyi Khong Betsy Rudnick Chris Libby Chris Regan Mac McLean Anchor Bay Films Falco Ink Ginsberg/Libby Ginsberg/Libby Click Communications 9242 Beverly Blvd 850 Seventh Avenue 6255 Sunset Blvd 6255 Sunset Blvd 13029-A Victory Blvd., #509 Beverly Hills, CA 90210 New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90028 Los Angeles, CA 90028 North Hollywood, CA 91606 P: 424.204.4164 P: 212.445.7100 P: 323.645.6812 P: 323.645.6814 P: 818.392.8863 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] mac@clickcommunications TEXAS KILLING FIELDS Synopsis Inspired by true events, this tense and haunting thriller follows Detective Souder (Sam Worthington), a homicide detective in a small Texan town, and his partner, transplanted New York City cop Detective Heigh (Jeffrey Dean Morgan) as they track a sadistic serial killer dumping his victims’ mutilated bodies in a nearby marsh locals call “The Killing Fields.” Though the swampland crime scenes are outside their jurisdiction, Detective Heigh is unable to turn his back on solving the gruesome murders. Despite his partner’s warnings, he sets out to investigate the crimes. Before long, the killer changes the game and begins hunting the detectives, teasing them with possible clues at the crime scenes while always remaining one step ahead. -

This Is a Test

‘THE WISHING TREE’ CAST BIOS JASON GEDRICK (Evan Farnsworth) – Jason Gedrick got his first acting break in his native Chicago when the film “Bad Boys,” starring Sean Penn, was filmed on location there in 1983. Then a high school student, he landed a role as an extra and Penn's encouragement inspired him to study acting in earnest. He soon landed leading roles in several films, including “Iron Eagle,” “Stacking” and “Heavenly Kid.” He co-starred with Meg Ryan and Kiefer Sutherland in “Promised Land” and in Ron Howard's “Backdraft,” as well as “Crossing the Bridge.” He simultaneously pursued stage work, starring on Broadway in Our Town with Don Ameche and Helen Hunt, as well as in the Off Broadway production of Mrs. Dally Has a Lover with Judith Ivey. His most recent foray on the stage was a production of Wrongturn at Lungfish, directed by Garry Marshall. Gedrick went on to star in such critically acclaimed series as Stephen Bochco's “Murder One,” “EZ Streets” created by Paul Haggis and Bobby Moresco, “Falcone” and NBC’s “Boomtown.” He has also recurred on hit shows such as “Ally McBeal” and “Desperate Housewives” and starred in the Hallmark Channel Original Movies “Hidden Places” and “The Christmas Choir.” He is currently co-starring in Showtime’s hit series “Dexter” and recently starred alongside Dustin Hoffman, Nick Nolte, Dennis Farina and Kevin Dunn in the HBO drama series “Luck.” Created by David Milch with director/producer Michael Mann, Gedrick played a degenerate gambler within the world of thoroughbred horse racing. ### RICHARD HARMON (Drew) – Richard Harmon started acting at the age of ten. -

The Officers'

April, 2012 No. 44 The Officers’ Log Tel: (516) 488-7400 Fax: (516) 488-4889 email: [email protected] Website: Italic.org ETHNIC ITALY CLEANSING? TAKES When La Casa Italiana was donated to Columbia University in 1927 along with a 20,000-volume library by the STOCK Paterno and Campagna Families, and endowed with a substantial maintenance fund from the Italian American It has been a bad year for Italy, beginning community, it was the capstone of our with the Costa Concordia shipwreck in heritage. Its mission was to diffuse January. And now, in March, an Italian Italian culture and to elevate Italian engineer working in Nigeria was Americans. That was then. murdered by kidnappers during a botched rescue attempt by British commandos. In 1990, the Italian Republic bought the 7-story palazzo and turned it over to a clutch His death was sad enough but the rescue of indifferent Columbia academics. Today, La Casa, functioning as the Italian Academy, attempt was made without informing the has been essentially cleansed of Italian Americans and shorn of its original mission. Italian government. Naturally, the Italians The Italic Institute has been working with the descendants of the Paterno-Campagna found this insulting, if not criminal. But it family to restore the purpose of La Casa. In that quest, we have appealed to Columbia feeds into the growing feeling by Italians University, New York State’s Attorney General and the Italian government itself. We that they are not being taken seriously, can report that while the Attorney General furnished us with important documentation, even by so-called allies like the UK. -

'The Big House and the Picket Fence'

CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE | NOVEMBER | NOVEMBER CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE ‘The big house and the picket fence’ Tonya Crowder still dreams that she and her fi ance, Roosevelt Myles—who’s been in prison for decades fi ghting what he says is a wrongful conviction—will one day build a life together somewhere “nice, quiet, and simple.” By MC 7 THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | NOVEMBER | VOLUME NUMBER IN THIS ISSUE T R - CITYLIFE televisionsitcomhasashowand THEATER @ 03 SightseeingTraveltipsfor moreartsandculturehappenings 20 ReviewDennisZačekstages ChicagofortheWorld’s WaitingforGodotagainyears ColumbianExpositionyesyou a erhisfi rsttimeanacademic PTB shouldtipyourservers debatebecomesaraciallycharged EC SKKH D EKS confl agrationinTheNiceties C LSK NEWS&POLITICS 22 PlaysofnoteTheNutcracker D P JR 05 Joravsky|PoliticsImagine returnstoHousewithafewtwistsa 30 ShowsofnoteHighonFire MEP M TDKR coveringMadiganandFoxxthe womanexploresherlimitsinQueen YoungMALasCafeterasand CEBW wayRepublicanrunmediacover ofSockPairingandWhyTorture morethisweek AEJL Trump IsWrongandthePeopleWho 32 TheSecretHistoryof SWDI BJ MS LoveThemisabrutalsendupof ChicagoMusicPiecesofPeace S WMD L G FEATURE Americanparanoia cutmostoftheirbrilliantsoulfunk EASN L 07 CriminalJusticeTonya 16 ComedyKorporateBidnessturns forotherpeople’srecords L CS C -J CEB N B Crowderstilldreamsthatshe toYouTubetohilariouslyhighlight 35 EarlyWarningsAirborne LCMDLC andherfi anceRooseveltMyles whatBlackChicagoBeLike ToxicEventKissKeithFullerton J F SF JH who’sbeeninprisonfordecades -

Animal House

Today's weather: Our second century of Portly sunny. excellence breezy. high : nea'r60 . Vol. 112 No. 10----= Student Center, University of Delaw-.re, Newark, Del-.ware 19716 Tuesday, October 7, 1986 Christina District residents to vote today 9n tax hike Schools need .more funds plained, is divided into two by Don Gordon parts: Staff Reporter • An allocation of money to . Residents of the Christina build a $5 million elementary School District will vote· today school south of Glasgow High on a referendum which could School and to renovate the 1 John Palmer Elementary J increase taxes for local homeowners to provide more School. THE REVIEW/ Kevin McCready t • A requirement for citizens money for district schools. Mother Nature strikes again - Last Wednesday's electrical storm sends bolts of lightning Dr. Michael Walls, to help pay fo~ supplies and superintendent of the upkeep of schools. through the night. The scene above Towne Court was captured from the fourth floor of Dickinson F. Christina School District, said "We don't have enough if the referendum is passed books to go around," Walls salary." and coordinator of the referen ing the day, or even having homeowners inside district stressed. Pam Connelly (ED 87) a dum, said he expects several two sessions which would at boundaries - which include In addition, citizens' taxes student-teacher at Downes thousand more persons to vote tend school during different residential sections of Newark would help pay for higher Elementary School, said new than did in 1984. parts of the year, Walls said. - will pay an additional 10 teacher salaries. -

Governor Quinn Proclaims Dennis Farina Day in Illinois

OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR PAT QUINN For Immediate Release Monday, July 29, 2013 Contact Press Line: (312) 814-3158 Brooke Anderson [email protected] Grant Klinzman [email protected] Governor Quinn Proclaims Dennis Farina Day in Illinois CHICAGO – Governor Pat Quinn today proclaimmed July 29, 2013 to be Dennis Farina Day in Illinois in honor of his outstanding contributions to the entertainment industry and for his many years of public service. WHEREAS, Illinois is a leader in supporting the arts, and acting has always been an important component of the artistic fabric of our state; and, WHEREAS, one of the most successful actors to come from the Land of Lincoln was Dennis Farina, who was born in Chicago to a Sicilian-American family on February 29, 1944; and, WHEREAS, Dennis Farina is unique in that he did not start acting until he was 37 years old, after serving in the military for 3 years and working for the Chicago Police Department for 18 years, where he spent most of his time in the burglary division; and, WHEREAS, while still working in the burglary division, Dennis Farina’s big break came when he was hired by director Michael Mann for the movie “Thief” (1981). This movie received critical acclaim, and they would go on to work together many times in the future; and, WHEREAS, after “Thief,” Dennisi Farina started acting in Chicago theater before being cast by Mann in a lead role for the 1986 TV series “Crime Story”; and, WHEREAS, Dennis Farina has acted in numerous other films including “Reindeer Games,” “Paparazzi,” -

![Thief Is a 1981 American Neo-Noir[4] Crime Film Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Mann in His Feature Film Debut](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2616/thief-is-a-1981-american-neo-noir-4-crime-film-written-produced-and-directed-by-michael-mann-in-his-feature-film-debut-4462616.webp)

Thief Is a 1981 American Neo-Noir[4] Crime Film Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Mann in His Feature Film Debut

From Wikipedia: • Thief is a 1981 American neo-noir[4] crime film written, produced and directed by Michael Mann in his feature film debut. It is based on the 1975 novel The Home Invaders: Confessions of a Cat Burglar by "Frank Hohimer" (the pen name of real-life jewel thief John Seybold). Thief marked the feature film debut of Michael Mann as director, screenwriter and executive producer, after five years in television drama. • Mann made his directorial debut with the TV movie The Jericho Mile. This was partly shot in Folsom Prison. Mann says that influenced the writing of Thief: • It probably informed my ability to imagine what Frank’s life was like, where he was from, and what those 12 or 13 years in prison were like for him. The idea of creating his character was to have somebody who has been outside of society. • An outsider who has been removed from the evolution of everything from technology to the music that people listen to, to how you talk to a girl, to what do you want with your life and how do you go about getting it. Everything that’s normal development, that we experience, he was excluded from, by design. In the design of the character and the engineering of the character, that was the idea.[ • Mann made James Caan do research as a thief for his role. • “So one of the most obvious things is it’d be pretty good if [James Caan] was as good at doing what Frank does as is Frank.” JAMES CAAN • James Caan's emotional several-minute monologue with Weld in a coffee shop is often cited as the film's high point, and Caan has long considered the scene his favorite of his career.[6] The actor liked the movie although he found the part challenging to play. -

Smoke Signals V40

Volume 40/Number 10 November 2007 1959 Administration’s Message Dear Residents: Welcome to November, my favorite time of year! I truly what it has become. Similarly, it is appropriate to remember enjoy the crisp weather, beautifully colored leaves, and and give thanks for our elected officials and those who serve upcoming holidays. Not only is it my birthday month, but it on the various Village commission’s and boards for the time also includes my favorite holiday: Thanksgiving. What could and effort they devote to conducting Village business on our be better than a day in which the focus is food, football, and behalf. family--no presents or other strings attached! As for our neighbors and fellow residents, it is hard to take As we approach Thanksgiving, it is important to take time a ride or walk around town without marveling at how won- to remember those things for which we should give thanks. derful our Village looks. We sometimes take for granted the My thoughts on what to be thankful for in the Village come beautiful trees and rolling hills, as well as the beautifully from not only my numerous years as a resident, but also from maintained yards and homes we have here in town. my time spent on the Planning And Zoning Commission, as Although this is a Village newsletter, I would be remiss in well as my time thus far as the newest Trustee on the Village not reminding us to remember at Thanksgiving the wonderful Board. As I look back over the last year, we have a great deal times with family and friends we have enjoyed over the last to be thankful for in Indian Head Park. -

Nancy Nayor Casting Resume January 2015 1

Nancy Nayor Casting Resume January 2015 1 NANCY NAYOR CASTING Office: 323-857-0151 / Cell: 213-309-8497 E-mail: [email protected] / Website: www.nancynayorcasting.com SENIOR VP OF FEATURE FILM CASTING, UNIVERSAL STUDIOS 1983-1997 BOY NEXT DOOR Director: Rob Cohen Producers: Universal, Blumhouse, Elaine Goldsmith-Thomas, Benny Medina, John Jacobs Cast: Jennifer Lopez, Kristin Chenoweth, John Corbett, Hill Harper KIDNAP Director: Luis Prieto Producers: Lorenzo Di Bonaventura, Elaine Goldsmith-Thomas, Erik Howsam, Lotus Entertainment, Gold Star Films Cast: Halle Berry, Jason George, Chris McGinn, Lew Temple, Sage Correa OUIJA Director: Stiles White Producers: Universal, Platinum Dunes, Blumhouse, Hasbro Cast: Olivia Cooke, Douglas Smith, Daren Kagasoff, Bianca Santos, Shelley Hennig THE MESSENGERS (CBS / CW SERIES) Director: Stephen Williams (pilot) Producers: Thunder Road Pictures, Eoghan O’Donnell, Ava Jamshidi Cast: Diogo Morgado, Shantel VanSanten, Jon Fletcher, Sofia Black-D’Elia, Joel Courtney, JD Pardo THE CONFIRMATION Director: Bob Nelson Producer: Todd Hoffman Cast: Clive Owen, Maria Bello, Patton Oswalt, Stephen Tobolowsky, Tim Blake Nelson, Robert Forster, Matthew Modine and Jaeden Lieberher EYE CANDY (MTV SERIES) Producers: Blumhouse, Christian Taylor Cast: Victoria Justice, Robert Hoffman, Kiersey Clemons, John Garet Stoker HOME Director: Dennis Iliadis Producers: Universal, Appian Way, Blumhouse, GK Films Cast: Topher Grace, Patricia Clarkson, Callan Mulvey, Genesis Rodriguez 21 AND OVER Directors: Scott Moore, Jon -

Blacklist Season 2 Digital Press Kit

BLACKLIST SEASON 2 DIGITAL PRESS KIT OVERVIEW For decades, ex-government agent Raymond “Red” Reddington (James Spader, “The Office,” “Boston Legal”) has been one of the FBI’s Most Wanted fugitives. Brokering shadowy deals for criminals across the globe, Red was known by many as “The Concierge of Crime.” Last season, he mysteriously surrendered to the FBI but now the FBI work for him as he identifies a “blacklist” of politicians, mobsters, spies and international terrorists. He will help catch them all… with the caveat that Elizabeth “Liz” Keen (Megan Boone, “Law & Order: Los Angeles”) continues to work as his partner. Red will teach Liz to think like a criminal and “see the bigger picture”… whether she wants to or not. Also starring are Diego Klattenhoff (“Homeland”), Harry Lennix (“Man of Steel”), Amir Arison (“Girls”) and Mozhan Marno (“House of Cards”). Jon Bokenkamp (“The Call,” “Taking Lives”), John Eisendrath (“Alias”), John Davis (“Predator,” "I, Robot," "Chronicle"), John Fox and Michael Watkins (“The X-Files”) serve as executive producers. “The Blacklist” is a production of Sony Pictures Television and Davis Entertainment. EXTRAS WHAT THE CRITICS SAID ABOUT SEASON 1 Entertainment Weekly “…it will win you over by being very good very quickly at exactly what it wants to be. “ “James Spader lets the charisma rip…” “…Megan Boone sparks nicely with Spader and confidently claims the heroic center of this action packed mystery thriller.” “THE BLACKLIST starts with a well-produced bang that’ll hook you with the promise that it can be