Willibald Pirckheimer and the Nuernberg City Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herzogenaurach Zirndorf Langenzenn

Reichmannsdorf Lonnershof Untermelsendorf Oberköst Unterköst Weiher Rothensand Debersdorf Sambach Ellersdorf Obermelsendorf Hopfenmühle Wingersdorf Unterstürmig Burg Feuerstein Oberndorf Thüngbach Mitterberg 394 Maierhof Steppach Niedermirsberg Wind 337 Großbuchfeld Decheldorf Kleinbuchfeld 298 332 Trailsdorf Neuses Breitenbach Kammerforst 338 360 a.d. Regnitz N erg 356 euseser B Lohmühle P Jungenhofen Neuses Über- öppelberg Rotenberg 361 Eckersbach 510 Unter- Eckartsmühle Kauernhofen Poxstall Rüssenbach SCHLÜSSELFELD Albach Schweinbach 334 Schnaid 335 Zentbechhofen Schlammersdorf Eggolsheim 319 Pommersfelden 500 350 Mäusgraben Stolzenroth Hallerndorf 384 Reumannswind Rambach Eck Mühlhausen tersber ögelste Steinberg ers Rit g Markt K in bacher Höhe W ch eißer Berg bra 305 Markt e E 498 380 506 Weidlesberg h 360 Kreuzberg Pautzfeld Thüngfeld ic Wachenroth e 297 316 517 R einberg Greuth Rettern W Markt Limbach 344 Volkersdorf Stiebarlimbach Oberndorf Reifenberg Possenfelden Lempenmühle 505 328 507 Neumühle NSG R zel etter r Kan 301 ne Attelsdorf 310 Gredel- mark Knock Mittler- Simmersdorf Bammersdorf weilersbach Pretzfeld Kleinwachenroth Hammermühle Förtschwind Tannen be Schlüsselfeld Schirnsdorf Jägersburg rg 315 347 be eebe NSG Ehrlersheim Horbach erchen rg chn rg Jägersburg Lach L S uselberg 379 306 Forst M Fürstenforst Elsendorf 310 73 Limbacher 330 Wintergartsgreuth 330 r B Kolmreuth llen Willersdorf Rotes Aue erg Weilersbach che ber Hölzer S g 340 Burghaslach ißenb Höchstadt Nord Bösenbechhofen Kn n Gle erg 344 öcklei 320 363 340 3 -

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Edited by Theodore Hoelty-Nickel Valparaiso, Indiana The greatest contribution of the Lutheran Church to the culture of Western civilization lies in the field of music. Our Lutheran University is therefore particularly happy over the fact that, under the guidance of Professor Theodore Hoelty-Nickel, head of its Department of Music, it has been able to make a definite contribution to the advancement of musical taste in the Lutheran Church of America. The essays of this volume, originally presented at the Seminar in Church Music during the summer of 1944, are an encouraging evidence of the growing appreciation of our unique musical heritage. O. P. Kretzmann The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Table of Contents Foreword Opening Address -Prof. Theo. Hoelty-Nickel, Valparaiso, Ind. Benefits Derived from a More Scholarly Approach to the Rich Musical and Liturgical Heritage of the Lutheran Church -Prof. Walter E. Buszin, Concordia College, Fort Wayne, Ind. The Chorale—Artistic Weapon of the Lutheran Church -Dr. Hans Rosenwald, Chicago, Ill. Problems Connected with Editing Lutheran Church Music -Prof. Walter E. Buszin The Radio and Our Musical Heritage -Mr. Gerhard Schroth, University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill. Is the Musical Training at Our Synodical Institutions Adequate for the Preserving of Our Musical Heritage? -Dr. Theo. G. Stelzer, Concordia Teachers College, Seward, Nebr. Problems of the Church Organist -Mr. Herbert D. Bruening, St. Luke’s Lutheran Church, Chicago, Ill. Members of the Seminar, 1944 From The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church, Volume I (Valparaiso, Ind.: Valparaiso University, 1945). -

6 X 10.5 Three Line Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76020-1 - The Negotiated Reformation: Imperial Cities and the Politics of Urban Reform, 1525-1550 Christopher W. Close Index More information Index Aalen, 26n20 consultation with Donauworth,¨ 37, Abray, Lorna Jane, 6 111–114, 116–119, 135–139, Aitinger, Sebastian, 75n71 211–214, 228, 254 Alber, Matthaus,¨ 54, 54n120, 54n123 consultation with Kaufbeuren, 41, 149, Albrecht, Archbishop of Mainz, 255 157–159, 174–176, 214, 250, 254 Altenbaindt, 188n33 consultation with Kempten, 167–168, Anabaptist Mandate, 156n42 249 Anabaptists, 143, 151, 153, 155 consultation with Memmingen, 32, 50, association with spiritualism, 156 51n109, 58, 167–168, 175 in Augsburg, 147, 148n12, 149, consultation with Nuremberg, 65, 68, 149n18 102, 104–108, 212–214, 250, 251 in Kaufbeuren, 17, 146–150, 148n13, consultation with Strasbourg, 95, 102, 154, 158, 161, 163, 167, 170, 214, 104–106, 251 232, 250, 253 consultation with Ulm, 33, 65, 68, in Munster,¨ 150, 161 73–76, 102, 104–108, 167, 189, Augsburg, 2, 11–12, 17, 23, 27, 38, 42, 192–193, 195–196, 204–205, 208, 45–46, 90, 95, 98, 151, 257 211–214, 250, 254 abolition of the Mass, 69, 101, controversy over Mathias Espenmuller,¨ 226n63 174–177, 250 admission to Schmalkaldic League, 71, economic influence in Burgau, 184 73–76 end of reform in Mindelaltheim, alliance with Donauworth,¨ 139–143, 203–208 163, 213, 220 Eucharistic practice, 121 Anabaptist community, 147, 149 fear of invasion, 77, 103n80 April 1545 delegation to Kaufbeuren, Four Cities’ delegation, 144–146, 160–167 167–172, -

The German Princes' Responses to the Peasants' Revolt of 1525

Central European History 40 (2007), 219–240. Copyright # Conference Group for Central European History of the American Historical Association DOI: 10.1017/S0008938907000520 Printed in the USA The German Princes’ Responses to the Peasants’ Revolt of 1525 Thomas F. Sea HE German Peasants’ Revolt of 1525 represented an unprecedented challenge to the princes and other petty political rulers of the areas involved. While localized uprisings had occurred with increasing fre- T 1 quency in the decades prior to the 1525 revolt and an uneasy awareness of growing levels of peasant discontent was widespread among most rulers of southern and central German lands, the extent of the major rebellion that devel- oped in early 1525 took everyone by surprise. No one was prepared to respond, either militarily or through more peaceful means. Even the Swabian League, the peacekeeping alliance of Imperial princes, prelates, nobility, and cities that even- tually assumed primary responsibility for suppressing the revolt, did little to mobilize its resources for almost six months after the first appeals for help from its members against disobedient subjects reached it.2 When the League did mobilize, its decision created further problems for League members, since most sent their required contingents to the League’s forces only to discover that they needed the troops badly themselves once the revolt spread to their own lands. Since the Council of the Swabian League adamantly refused to return any members’ troops because this would hinder the League’s own ability to suppress the peasant disorders, many members found themselves vir- tually defenseless against the rebels. -

Verbände Kreisjugendring Hof

Verbände Kreisjugendring Hof Adventjugend (AJ) Selbitz Adventjugend CPA Hüttung Bund Deutscher Karnevaljugend (BDK-J) Bad Steben Jugend der Karnevalsgemeinschaft Bad Steben Helmbrechts Jugend FeGe 1970 u. Stadtgarde Helmbrechts Töpen Jugend Karnevalsgesellschaft Töpen Bund der Deutschen Katholischen Jugend (BDKJ) Bad Steben Kath. Jugend Bad Steben BDKJ Jugend Bernhard Lichtenberg St. Marien Feilitzsch Feilitzsch Helmbrechts BDKJ Enchenreuth Helmbrechts BDKJ Helmbrechts Hof BDKJ Regionalverband Hof-Kulmbach BDKJ Jugend Bernhard Lichtenberg St. Konrad Konradsreuth Konradsreuth Münchberg Kath. Jugend Ministranten Münchberg u. Sparneck Münchberg Kolpingjugend Münchberg Naila Kath. Jugend Naila Oberkotzau Kath. Jugend Oberkotzau Rehau Kath. Jugend Rehau Schwarzenbach/Saale Kath. Jugend Schwarzenbach/Saale Bund Deutscher Pfadfinderinnen und Pfadfinder (BDP) Sparneck BdP Stamm Phönix Bayerische Fischereijugend (BFJ) Helmbrechts Jugend Fischereiverein Helmbrechts Lichtenberg Jugend Fischereiverein Lichtenberg e.V. Münchberg Fischereijugend Münchberg Naila Fischereijugend Naila Schwarzenbach/Saale Jugend Fischereiverein Förmitzspeicher e.V. Weißdorf Fischereijugend Weißdorf Bayerische Jungbauernschaft (BJB) Döhlau Evangelische Landjugend Kautendorf Feilitzsch Landjugend Zedtwitz Hof Landjugend Kreisverband Hof Konradsreuth Evangelische Landjugend Oberpferdt Konradsreuth Landjugend Reuthlas Münchberg Landjugend Plösen e.V. Naila Landjugend Marxgrün Regnitzlosau Landjugend Regnitzlosau Schauenstein Landjugend Neudorf Schwarzenbach/Saale Landjugend -

Geothermal Prospection in NE Bavaria

Geo Zentrum 77. Jahrestagung der DGG 27.-30. März 2017 in Potsdam Nordbayern Geothermal Prospection in NE Bavaria: 1 GeoZentrum Nordbayern Crustal heat supply by sub-sediment Variscan granites in the Franconian basin? FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg *[email protected] 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 Schaarschmidt, A. *, de Wall, H. , Dietl, C. , Scharfenberg, L. , Kämmlein, M. , Gabriel, G. Leibniz Institute for Applied Geophysics, Hannover Bouguer-Anomaly Introduction with interpretation Late-Variscan granites of different petrogenesis, composition, and age constitute main parts of the Variscan crust in Northern Bavaria. In recent years granites have gained attention for geothermal prospection. Enhanced thermal gradients can be realized, when granitic terrains are covered by rocks with low thermal conductivity which can act as barriers for heat transfer (Sandiford et al. 1998). The geothermal potential of such buried granites is primarily a matter of composition and related heat production of the granitoid and the volume of the magmatic body. The depth of such granitic bodies is critical for a reasonable economic exploration. In the Franconian foreland of exposed Variscan crust in N Bavaria, distinct gravity lows are indicated in the map of Bouguer anomalies of Germany (Gabriel et al. 2010). Judging from the geological context it is likely that the Variscan granitic terrain continues into the basement of the western foreland. The basement is buried under a cover of Permo- Mesozoic sediments (Franconian Basin). Sediments and underlying Saxothuringian basement (at depth > 1342 m) have been recovered in a 1390 m deep drilling located at the western margin of the most dominant gravity low (Obernsees 1) and subsequent borehole measurements have recorded an increased geothermal gradient of 3.8 °C/100 m. -

Steine Und Geschichte(N) SÜHNEKREUZE – GEDENKEN an MORD UND TOD Entfernung: Ca

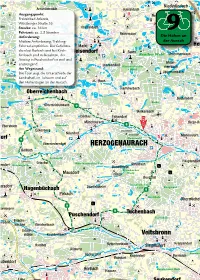

Steine und Geschichte(n) SÜHNEKREUZE – GEDENKEN AN MORD UND TOD Entfernung: ca. 50 km Neben diesen steinernen Grenzmarken finden sich im Land kreis Fürth auch Steine in Kreuzform. Die einen erinnern an ein ziviles Unglück Vorwort oder einen militärischen Waffengang, bei denen jemand ums Leben Sechs Radtouren im Land kreis Fürth. Durch die Täler und über die kam. Die anderen – und das sind die meisten – wurden zur Sühne Höhen des Rangau radeln Sie und erkunden dabei Geschichte und von Mord oder Totschlag aufgestellt, wie etwa das große Geschichten. Steinerne Zeugen erzählen. Von Königen, Fürsten und Steinmonument in Neuses belegt: Hier ging der herrschende Unfriede Feldherren und dem ein fachen Volk. zwischen Bauer Conz Lederer und seinen Dorfgenossen Rudolt und Vogt irgendwann einmal tödlich aus. Um die damit begonnene Fehde Ge mein sames Kennzeichen aller Touren: Familienfreundlichkeit. Meist zu beenden und Blutrache zu vermeiden, schlossen die betroffenen nutzen Sie wenig befahrene Nebenstraßen und bequeme Radwege. Parteien untereinander eine Sühnever ein ba rung. Bis ins 17. Jh. hinein Alle Start- und Zielpunkte der sechs Rangau-Touren haben einen gab es solche Abkommen, zu denen auch das Aufstellen eines Bahn- An schluss. Kreuzes gehörte. Stand: 8.9.2017 Karten HOHENZOLLERN – DAS ERBE DER BURGHERREN Karte am Ende des Dokuments in höherer Be son ders ge prägt wurde die Region von den Hohenzollern, die im Auflösung. Franken des 12. Jh. zunächst als Burggrafen von Nürn berg Fuß fassten. Als sie Mitte des 13. Jh. in den Besitz von Cadolzburg gelangten, hatten sie ihre künftige Machtbasis gefunden. Kluge Königstreue, ein Händchen für Hausmachtpolitik und einiges Geschick beim Erwerb von Territorien konsolidierten den Aufstieg in den begehrten Reichsfürstenstand. -

Herzogenaurach Langenzenn

Reichmannsdorf Lonnershof Untermelsendorf Oberköst Unterköst Weiher Rothensand Debersdorf Sambach Ellersdorf Obermelsendorf Hopfenmühle Wingersdorf Unterstürmig Burg Feuerstein Oberndorf Thüngbach Mitterberg 394 Maierhof Steppach Niedermirsberg Wind 337 Großbuchfeld Decheldorf Kleinbuchfeld 298 332 Trailsdorf Neuses Breitenbach Kammerforst 338 360 a.d. Regnitz N erg 356 euseser B Lohmühle P Jungenhofen Neuses Über- öppelberg Rotenberg 361 Eckersbach 510 Unter- Eckartsmühle Kauernhofen Poxstall Rüssenbach SCHLÜSSELFELD Albach Schweinbach 334 Schnaid 335 Zentbechhofen Schlammersdorf Eggolsheim 319 Pommersfelden 500 350 Mäusgraben Stolzenroth Hallerndorf 384 Reumannswind Rambach Eck Mühlhausen tersber ögelste Steinberg ers Rit g Markt K in bacher Höhe W ch eißer Berg bra 305 Markt e E 498 380 506 Weidlesberg h 360 Kreuzberg Pautzfeld Thüngfeld ic Wachenroth e 297 316 517 R einberg Greuth Rettern W Markt Limbach 344 Volkersdorf Stiebarlimbach Oberndorf Reifenberg Possenfelden Lempenmühle 505 328 507 Neumühle NSG R zel etter r Kan 301 ne Attelsdorf 310 Gredel- mark Knock Mittler- Simmersdorf Bammersdorf weilersbach Pretzfeld Kleinwachenroth Hammermühle Förtschwind Tannen be Schlüsselfeld Schirnsdorf Jägersburg rg 315 347 be eebe NSG Ehrlersheim Horbach erchen rg chn rg Jägersburg Lach L S uselberg 379 306 Forst M Fürstenforst Elsendorf 310 73 Limbacher 330 Wintergartsgreuth 330 r B Kolmreuth llen Willersdorf Rotes Aue erg Weilersbach che ber Hölzer S g 340 Burghaslach ißenb Höchstadt Nord Bösenbechhofen Kn n Gle erg 344 öcklei 320 363 340 3 -

Updateliste Revision: 1.0 Landkreis Neustadt/WN Seite 1 Von 5

Info-Dokument Updateliste Revision: 1.0 Landkreis Neustadt/WN Seite 1 von 5 Datum Uhrzeit Ort Feuerwehr 15:00 Hagendorf 15:00 Reinhardsrieth 15:20 Pfrentsch 13.02.2019 Gerätehaus Waidhaus 15:20 Reichenau 15:40 FL NEW Land 2/2 (Schmidt Matthias) 16:00 Waidhaus 18:30 Eslarn 13.02.2019 Gerätehaus Eslarn 18:30 FL NEW Land 2/1 (Kleber Thomas) 15:00 Großenschwand 15:00 Kleinschwand 14.02.2019 15:20 Gerätehaus Tännesberg Woppenrieth 15:20 Tännesberg 15:20 FL NEW Land 2/3 (Demleitner Christian) 17:30 Burgtreswitz 17:50 Gaisheim 18:10 Etzgersrieth 18:10 Gröbenstädt 18:30 Heumaden 14.02.2019 Gerätehaus Moosbach 18:30 Rückersrieth 18:50 Saubersrieth 18:50 Ödpielmannsberg 19:10 Tröbes 19:10 Moosbach 15:00 Döllnitz b. Leuchtenberg 15:20 Lerau 15.02.2019 15:20 Gerätehaus Leuchtenberg Wittschau/Preppach 16:00 Michldorf 16:40 Leuchtenberg Erstellt durch: R. Höcht Freigabe durch: S Schieder am: 11.01.2019 am: 11.01.2019 Info-Dokument Updateliste Revision: 1.0 Landkreis Neustadt/WN Seite 2 von 5 15:00 Altenstadt/VOH 15:20 Böhmischbruck 15:40 Kaimling 16:00 Oberlind 19.02.2019 Gerätehaus Vohenstrauß 16:20 Roggenstein 16:40 Waldau 17:00 FL NEW Land 2 (Weig Martin) 17:20 Vohenstrauß 15:00 Lennesrieth 15:20 Oberbernrieth 20.02.2019 Gerätehaus Waldthurn 15:20 Spielberg 15:40 Waldthurn 17:30 Burkhardsrieth 17:50 Lohma 17:50 Spielhof 20.02.2019 Gerätehaus Pleystein 18:10 Miesbrunn 18:10 Vöslesrieth 18:30 Pleystein 15:00 Flossenbürg 15:40 Bergnetsreuth 21.02.2019 Gerätehaus Floß 16:00 Altenhammer 16:20 Floß 18:00 Waldkirch 18:20 Brünst 21.02.2019 18:40 Gerätehaus Georgenberg Neudorf b. -

Kreistagsliste Der CSU Im Landkreis Fürth

Kreistagsliste der CSU im Landkreis Fürth Listenplatz Name, Vorname Ortsverband 1 Dießl Matthias Seukendorf 2 Obst Bernd Cadolzburg 3 Kistner Marco Veitsbronn 4 Seifert Adelheid Zirndorf 5 Reuther Christoph Langenzenn 6 Huber Birgit Oberasbach 7 Zehmeister Thomas Großhabersdorf 8 Rietzke Stefanie Roßtal 9 Höfer Bertram Stein 10 Egerer Jutta Cadolzburg 11 Klaski Bernd Zirndorf 12 Habel Jürgen Langenzenn 13 Schlager Anni Langenzenn 14 Emmert Uwe Wilhermsdorf 15 Zimmermann Bernd Obermichelbach 16 Krach Renate Roßtal 17 Eder Leonhard Tuchenbach 18 Keller Günther Zirndorf 19 Wiegandt Bodo Oberasbach 20 Schuller Sandra Seukendorf 21 Ostendorf Jens Stein 22 Rauch Ursula Zirndorf-Südwest 23 Augustin Claudia Cadolzburg Kreistagsliste der CSU im Landkreis Fürth Listenplatz Name, Vorname Ortsverband 24 Haag Hans Cadolzburg 25 Redlingshöfer Richard Veitsbronn 26 Hohmann Uta Roßtal 27 Haas Marco Oberasbach 28 Gebhardt Bastian Stein 29 Köninger Peter Wilhermsdorf 30 Zill Beate Oberasbach 31 Röhn Roland Zirndorf 32 Weghorn Doreen Langenzenn 33 Müller Günther Ammerndorf 34 Heckel Klaus Stein 35 Maurer Ute Großhabersdorf 36 Gerstner Markus Oberasbach 37 Hüfner Sven-Eric Zirndorf-Weiherhof 38 Hechtel Bettina Stein 39 Madinger Klaus Puschendorf 40 Besendörfer Hildegard Cadolzburg 41 Bauer Stefanie Obermichelbach 42 Greller Peter Veitsbronn 43 Ruscica Pruy Rossella Zirndorf 44 Schmitt Lothar Oberasbach 45 Prießnitz Matthias Roßtal 46 Herrmann Alexander Langenzenn Kreistagsliste der CSU im Landkreis Fürth Listenplatz Name, Vorname Ortsverband 47 Döhla Petra -

A Study of Early Anabaptism As Minority Religion in German Fiction

Heresy or Ideal Society? A Study of Early Anabaptism as Minority Religion in German Fiction DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ursula Berit Jany Graduate Program in Germanic Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Professor Barbara Becker-Cantarino, Advisor Professor Katra A. Byram Professor Anna Grotans Copyright by Ursula Berit Jany 2013 Abstract Anabaptism, a radical reform movement originating during the sixteenth-century European Reformation, sought to attain discipleship to Christ by a separation from the religious and worldly powers of early modern society. In my critical reading of the movement’s representations in German fiction dating from the seventeenth to the twentieth century, I explore how authors have fictionalized the religious minority, its commitment to particular theological and ethical aspects, its separation from society, and its experience of persecution. As part of my analysis, I trace the early historical development of the group and take inventory of its chief characteristics to observe which of these aspects are selected for portrayal in fictional texts. Within this research framework, my study investigates which social and religious principles drawn from historical accounts and sources influence the minority’s image as an ideal society, on the one hand, and its stigmatization as a heretical and seditious sect, on the other. As a result of this analysis, my study reveals authors’ underlying programmatic aims and ideological convictions cloaked by their literary articulations of conflict-laden encounters between society and the religious minority. -

Dating the Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was the 16th-century religious, political, intellectual and cultural upheaval that splintered Catholic Europe, setting in place the structures and beliefs that would define the continent in the modern era. In northern and central Europe, reformers like Martin Luther, John Calvin and Henry VIII challenged papal authority and questioned the Catholic Church’s ability to define Christian practice. They argued for a religious and political redistribution of power into the hands of Bible- and pamphlet-reading pastors and princes. The disruption triggered wars, persecutions and the so-called Counter-Reformation, the Catholic Church’s delayed but forceful response to the Protestants. DATING THE REFORMATION Historians usually date the start of the Protestant Reformation to the 1517 publication of Martin Luther’s “95 Theses.” Its ending can be placed anywhere from the 1555 Peace of Augsburg, which allowed for the coexistence of Catholicism and Lutheranism in Germany, to the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia, which ended the Thirty Years’ War. The key ideas of the Reformation—a call to purify the church and a belief that the Bible, not tradition, should be the sole source of spiritual authority—were not themselves novel. However, Luther and the other reformers became the first to skillfully use the power of the printing press to give their ideas a wide audience. 1 Did You Know? No reformer was more adept than Martin Luther at using the power of the press to spread his ideas. Between 1518 and 1525, Luther published more works than the next 17 most prolific reformers combined. THE REFORMATION: GERMANY AND LUTHERANISM Martin Luther (1483-1546) was an Augustinian monk and university lecturer in Wittenberg when he composed his “95 Theses,” which protested the pope’s sale of reprieves from penance, or indulgences.