Frame Analysis and the Rock Scenes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

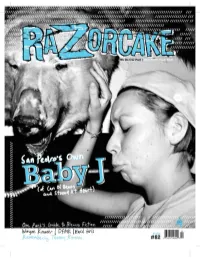

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

Mythopoesis, Scenes and Performance Fictions: Two Case Studies (Crass and Thee Temple Ov Psychick Youth)

This is an un-peer reviewed and un-copy edited draft of an article submitted to Parasol. Mythopoesis, Scenes and Performance Fictions: Two Case Studies (Crass and Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth) Simon O’Sullivan, Goldsmiths College, London Days were spent in fumes from the copying machine, from the aerosols and inks of the ‘banner production department’ – bed sheets vanished – banners appeared, from the soldering of audio, video, and lighting leads. The place stank. The garden was strewn with the custom made cabinets of the group’s equipment, the black silk- emulsion paint drying on the hessian surfaces. Everything matched. The band logo shone silver from the bullet-proof Crimpeline of the speaker front. Very neat. Very fetching. Peter Wright (quoted in George Berger, The Story of Crass) One thing was central to TOPY, apart from all the tactics and vivid aspects, and that was that beyond all else we desperately wanted to discover and develop a system of practices that would finally enable us and like minded individuals to consciously change our behaviours, erase our negative loops and become focussed and unencumbered with psychological baggage. Genesis P-Orridge, Thee Psychick Bible In this brief article I want to explore two scenes from the late 1970s/1980s: the groups Crass (1977-84) and Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth (1981-). Both of these ‘performance fictions’ (as I will call them) had a mythopoetic character (they produced – or fictioned – their own world), perhaps most evident in the emphasis on performance and collective participation. They also involved a focus on self- determination, and, with that, presented a challenge to more dominant fictions and consensual reality more generally.1 1. -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

'The Hippies Now Wear Black' Crass and the Anarcho

‘The hippies now wear black’ | Socialist History – The Hippies Now Wear Black | Richard Cross ‘The hippies now wear black’ Crass and the anarcho-punk movement, 1977-1984 ew social historians of Britain in the late 1970s would dismiss the influence that the emergent punk rock movement exerted in the fields of music, fashion and design, art and F aesthetics. Most would accept too that the repercussions and reverberations of punk’s challenge to suffocating norms against which it rebelled so vehemently continue to be felt in the present tense.1 Behind the tabloid preoccupation with the Sex Pistols, a maelstrom of bands, including such acts as The Damned, The Buzzcocks, Slaughter and the Dogs, X-Ray Spex and The Raincoats, together redefined the experience of popular music and its relationship to the cultural mainstream. Bursting into the headlines as the unwelcome gatecrasher of the Silver Jubilee celebrations, punk inspired the misfits and malcontents of a new generation to reject the constraints of an exhausted post-war settlement, and to rail against boredom, alienation, wage-slavery, and social conformity. Yet, in retrospect, the purity of punk’s ‘total rejection’ of ‘straight society’ (if not seen as comprised from the outset) appears fleeting. By the tail-end of 1977, the integrity of punk’s critique seemed to be fast unravelling. What had declared itself to be an uncompromising cultural and musical assault on an ossified status quo, was become increased ensnared in the compromises of ‘incorporation’ and ‘commodification’. Punk bands which had earlier denounced the corporate big- time were signing lucrative deals with major record labels, keen to package and promote their rebellious messages. -

Authenticity, Politics and Post-Punk in Thatcherite Britain

‘Better Decide Which Side You’re On’: Authenticity, Politics and Post-Punk in Thatcherite Britain Doctor of Philosophy (Music) 2014 Joseph O’Connell Joseph O’Connell Acknowledgements Acknowledgements I could not have completed this work without the support and encouragement of my supervisor: Dr Sarah Hill. Alongside your valuable insights and academic expertise, you were also supportive and understanding of a range of personal milestones which took place during the project. I would also like to extend my thanks to other members of the School of Music faculty who offered valuable insight during my research: Dr Kenneth Gloag; Dr Amanda Villepastour; and Prof. David Wyn Jones. My completion of this project would have been impossible without the support of my parents: Denise Arkell and John O’Connell. Without your understanding and backing it would have taken another five years to finish (and nobody wanted that). I would also like to thank my daughter Cecilia for her input during the final twelve months of the project. I look forward to making up for the periods of time we were apart while you allowed me to complete this work. Finally, I would like to thank my wife: Anne-Marie. You were with me every step of the way and remained understanding, supportive and caring throughout. We have been through a lot together during the time it took to complete this thesis, and I am looking forward to many years of looking back and laughing about it all. i Joseph O’Connell Contents Table of Contents Introduction 4 I. Theorizing Politics and Popular Music 1. -

The Politics of Anarchy in Anarcho Punk,1977-1985

No Compromise with Their Society: The Politics of Anarchy in Anarcho Punk,1977-1985 Laura Dymock Faculty of Music, Department of Music Research, McGill University, Montréal September, 2007 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts, Musicology © Laura Dymock, 2007 Libraryand Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-38448-0 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-38448-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Punk Lyrics and Their Cultural and Ideological Background: a Literary Analysis

Punk Lyrics and their Cultural and Ideological Background: A Literary Analysis Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magisters der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens Universität Graz vorgelegt von Gerfried AMBROSCH am Institut für Anglistik Begutachter: A.o. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Hugo Keiper Graz, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 3 INTRODUCTION – What Is Punk? 5 1. ANARCHY IN THE UK 14 2. AMERICAN HARDCORE 26 2.1. STRAIGHT EDGE 44 2.2. THE NINETEEN-NINETIES AND EARLY TWOTHOUSANDS 46 3. THE IDEOLOGY OF PUNK 52 3.1. ANARCHY 53 3.2. THE DIY ETHIC 56 3.3. ANIMAL RIGHTS AND ECOLOGICAL CONCERNS 59 3.4. GENDER AND SEXUALITY 62 3.5. PUNKS AND SKINHEADS 65 4. ANALYSIS OF LYRICS 68 4.1. “PUNK IS DEAD” 70 4.2. “NO GODS, NO MASTERS” 75 4.3. “ARE THESE OUR LIVES?” 77 4.4. “NAME AND ADDRESS WITHHELD”/“SUPERBOWL PATRIOT XXXVI (ENTER THE MENDICANT)” 82 EPILOGUE 89 APPENDIX – Alphabetical Collection of Song Lyrics Mentioned or Cited 90 BIBLIOGRAPHY 117 2 PREFACE Being a punk musician and lyricist myself, I have been following the development of punk rock for a good 15 years now. You might say that punk has played a pivotal role in my life. Needless to say, I have also seen a great deal of media misrepresentation over the years. I completely agree with Craig O’Hara’s perception when he states in his fine introduction to American punk rock, self-explanatorily entitled The Philosophy of Punk: More than Noise, that “Punk has been characterized as a self-destructive, violence oriented fad [...] which had no real significance.” (1999: 43.) He quotes Larry Zbach of Maximum RockNRoll, one of the better known international punk fanzines1, who speaks of “repeated media distortion” which has lead to a situation wherein “more and more people adopt the appearance of Punk [but] have less and less of an idea of its content. -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #8: Music Boo-Hooray Catalog #8

Boo-Hooray Catalog #8: Music Boo-Hooray Catalog #8 Music Boo-Hooray is proud to present our eighth antiquarian catalog, dedicated to music artifacts and ephemera. Included in the catalog is unique artwork by Tomata Du Plenty of The Screamers, several incredible items documenting music fan culture including handmade sleeves for jazz 45s, and rare paste-ups from reggae’s entrance into North America. Readers will also find the handmade press kit for the early Björk band, KUKL, several incredible hip-hop posters, and much more. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Ben Papaleo, Evan, and Daylon. Layout by Evan. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Table of Contents 31. [Patti Smith] Hey Joe (Version) b/w Piss Factory .................. -

Exhibition Guide

TRICKING THE IMPOSSIBLE word and type · penny rimbaud and bracketpress exhibition guide IN THE BACKGROUND… AN INTRODUCTION by Christian Brett I first came to Penny’s work through a couple of manuscripts – Or Maybe Crass, saving up my dinner money to Tomorrow and This Crippled Flesh buy Feeding of the Five Thousand – which Pomona didn’t want to be when I was about 10 or 11 years old. involved in. When I first saw This dissertation, Censorship by Omission Twenty years later we would start Crippled Flesh I was so excited. It and the Economics of Truth (C4) working together and a great friend- was like being given the opportunity which Penny suggested publishing as ship has grown from that. to work on a William Burroughs text, a pamphlet. Gee suggested the name but more. So, with my partner Alice, ‘Bracket Press’ after my penchant for Our first meeting came about in 2003 began several years of revisiting and bracketing the folios in my book while I was typesetting books for revising the typesetting while trying designs. And so Bracketpress came publisher Mark Hodkinson at Pomona to get someone to take on the book into being and is also my trading Books. Mark had an idea to create a and publish it properly – John Calder, name. series of lyric books by English bands, Hamish Hamilton and Damien Hirst and asked if I had any ideas. The only being those who showed genuine The first pamphlet we published of one I thought worthwhile would be to interest. In late 2009 we revisited Penny’s work was Freedom is such a do a Crass lyric book – but to present the design and overhauled the core big word [2006]. -

“There Is No Authority but Yourself ”: the Individual and the Collective in British Anarcho-Punk

“There Is No Authority But Yourself ”: The Individual and the Collective in British Anarcho-Punk RICH CROSS You must learn to live with your own conscience, your own morality, your own decision, your own self. You alone can do it. There is no authority but yourself Crass Yes Sir, I Will 1983 Introduction British anarchist punk band Crass’s fifth studio album Yes Sir, I Will (released on the band’s own label in 1983) was the most challenging and demanding record the group had yet committed to vinyl. 1 Its tone was dark, the musical delivery harsh and disjointed, the political invective stark and unrelenting. The entire record seethed with anger, incredulity, and indignation. For the moment in which it was produced, Yes Sir, I Will was an entirely fitting testament to the position in which “anarcho-punk” now found itself. From its own origins in 1977, this dissident strand within British punk had connected with a new audience willing to take seriously the “revolutionary” cultural and political aspirations that punk rock had originally championed. Anarcho-punk concerned itself with urging the individual to prize themselves free of social conformity and the shackles of societal constraint, championing personal independence and the exercise of free will. At the same time, anarcho-punk declared, as an indivisible and parallel objective, its support for the liberation of the planet from the tyranny of the “war state” and the overthrow of the disfiguring and alienating capitalist system. These intertwined aims were pursued with both intense determination and unflagging self-belief. By 1983, however, the limitations and inadequacies of the new anarcho-punk movement had become as transparent as its evident strengths, even to the band that had served as the movement’s principal catalyst. -

Crass DIY Exposition ➨ 26/09/18 ➨ 22/12/18

1 place Attane F – 87500 Saint-Yrieix-la-Perche cdla www.cdla.info ❚ [email protected] ❚ http://lecdla.wordpress.com Lecentre tél. + 33 (0) 5 55 75 70 30 ❚ fax + 33 (0) 5 55 75 70 31 des livres d’artistes https://www.facebook.com/cdla.saintyrieixlaperche https://twitter.com/CdlaMathieu PARTENAIRES INSTITUTIONNELS ministère de la Culture – DRAC Nouvelle-Aquitaine, Région Nouvelle-Aquitaine, Ville de Saint-Yrieix-la-Perche, Conseil départemental de la Haute-Vienne. crass DIY exposition ➨ 26/09/18 ➨ 22/12/18 Il y a bientôt deux ans, je cherchais des informations sur le festival ICES1 et l’œuvre d’Anthony McCall «Landscape for Fire». Moteur de recherche aidant, je suis tombé sur des passages d’un livre de George Berger The Story of Crass (Oakland, PM Press, 2009). J’y découvre que ce sont Penny Rimbaud, Gee Vaucher et quelques autres, membres d’un groupe de musique expérimentale nommé «Exit», qui vont aider Anthony McCall à mettre en œuvre cette pièce («Exit» est la continuation de deux ensembles de musique expérimentale, le Stanford Rivers Quartet puis Ceres Confusion). Nos premières œuvres, influencées par les théories d’artistes du Bauhaus et par des compositeurs comme Berio ou Varèse portaient sur la relation entre le son et un imaginaire visuel. A partir de là nous avons développé une méthode de notation utilisant des tracés sur du papier millimétré pour déterminer la durée, la hauteur et l’intensité ; les partitions qui en résultaient avaient plus à voir avec la peinture qu’avec la musique. De la même façon, en plaçant une grille sur n’importe quelle image trouvée, nous pouvions la traduire en sons.2 Penny Rimbaud dans : George Berger The Story of Crass (Oakland, PM Press, 2009), page 28. -

Universidad Bolivariana De Santiago De Chile Escuela De Antropología Social

UNIVERSIDAD BOLIVARIANA DE SANTIAGO DE CHILE ESCUELA DE ANTROPOLOGÍA SOCIAL MICRO IDENTIDADES CULTURALES URBANAS EMERGENTES: JÓVENES, PUNK E IDENTIDAD CULTURAL. UNA MIRADA AL PARAÍSO CIUDADANO DE HOY EN DÍA, DESDE UN GRUPO DE JÓVENES PUNK DE SANTIAGO DE CHILE. TESIS PRESENTADA PARA OPTAR AL TÍTULO DE ANTROPÓLOGO SOCIAL Y AL GRADO ACADÉMICO DE LICENCIADO EN ANTROPOLOGÍA SOCIAL TESISTA: CHRISTIAN CASTRO BEKIOS PROFESORA GUÍA: BÁRBARA MATUS MADRID ANTROPÓLOGA SOCIAL SANTIAGO DE CHILE, JULIO DE 2004 INDICE Página I. INTRODUCCIÓN....................................................................................................................4 II. AGRADECIMIENTOS...........................................................................................................11 III. FUNDAMENTACIÓN DEL TEMA DE TESIS....................................................................12 IV. RELEVANCIA Y ALCANCE DEL TEMA..........................................................................17 V. DISCUSIÓN BIBLIOGRÁFICA............................................................................................19 VI. NATURALEZA DEL ESTUDIO A REALIZAR..................................................................35 VII. OBJETIVOS DE LA INVESTIGACIÓN..............................................................................37 VIII. MARCO TEÓRICO...............................................................................................................37 IX. LOS PASOS METODOLÓGICOS DESARROLLADOS EN ESTA INVESTIGACIÓN.........................................................................................................94