Kircul.Pdf (4.822Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 099 261 SO 007 956 TITLE Urban

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 099 261 SO 007 956 TITLE Urban Growth: Today's Challenge. Seventh Grade, Social Studies. INSTITUTION Baltimore City Public Schools, Md. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 180p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$9.00 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *City Planning; Curriculum Guides; Discovery Learning; Educational Objectives; Fundamental Concepts; Grade 7; *Human Geography; Inquiry Training; Interdisciplinary Approach; Learning Activities; Resource Materials; Skill Development; *Social Studies; *Urbanization; *Urban Studies IDENTIFIERS Baltimore; Maryland ABSTRACT This course of study offers to seventh grade pupils themes which are designed to clarify the meaning and importance of the urban environment in which they live. The guide is about people in the cities and about the planning, growth, and problems of cities. Themes cover the Baltimore city area, urbanization in Maryland, urbanization in the United States, and urbanization in the world. The disciplines of history, economics, geography, political science, sociology, and anthropology are woven into the content and learning activities. Techniques of discovery and inquiry are recommended. Specific learning experiences provide opportunities for theuse of skills in a functional manner. A selected bibliography on city, state, and federal relationships in government; a list of selected nonprint media on city, state, and federal relationships; and an annotated bibliography replace the use of a single textbook. Each of the four themes in introduced; has a list of objectives; and has schematically related content, understandings and generalizations, sample activities, and suggested skills. (Author/KSM) V 66616,...`5. r Nir -r&,.vttfh, , a 4 66 466 116 . c .7 a.:A '... i d ' 40114 t , yt? , ,V., t ,;..A 4 .4 .1.1 '''"('''' :PAT't.pr' '1. -

Grants for Maryland (FYE 2013-2015) LIST of SELECTED APPROVED and PAID GRANTS $50,000 and LARGER / FY 2013 - 2015

The Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation, Inc. 20152014 GrantsGrants forfor MarylandMaryland VolumeVolume 8 3 With total assets of just over $2 billion, The Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation is one of the largest private foundations in the United States. Here are a few highlights: The Weinberg Foundation provides approximately $100 The Weinberg Foundation has million in annual grants to nonprofits that provide ■■ direct services to low-income and vulnerable individuals Developed and initiated Together We Care: Making Maryland – by 2020 – the Best Place to Grow Old. and families, primarily in the US and Israel. Grants The ultimate goal of this effort is to provide a “no wrong are focused on meeting basic needs and enhancing door” approach in Maryland to a variety of services an individual’s ability to achieve self-sufficiency with and supports for older adults. To date, the Weinberg Foundation has provided $4.4 million in grants to build emphasis on older adults, the Jewish community, and the framework for this initiative that will create a model our hometown communities of Maryland, Northeastern of comprehensive care allowing more older adults to age Pennsylvania, and Hawaii. with dignity and independence. In the following pages, the Foundation has identified ■■ Launched Baltimore City’s Early Childhood Initiative and selected grants of $50,000 or more that were Better Together, which seek to ensure children enter kindergarten healthy and ready to learn. Since 2011, approved and distributed within Maryland during the the Weinberg Foundation has committed a total of $20 past three years. During that time, the Foundation million to increase access to early childhood education approved nearly 300 grants totaling $102.5 million. -

Baltimore City Baltimore County Isabel Mercedes Cumming Kelly B

Baltimore City Baltimore County Isabel Mercedes Cumming Kelly B. Madigan Inspector General Inspector General 100 N Holliday St., Ste 635 400 Washington Ave Baltimore, MD 21202 Towson, MD 21204 December 8, 2020 Mayor Brandon M. Scott County Executive John A. Olszewski, Jr. City Hall, Room 250 Historic Courthouse 100 N. Holliday Street 400 Washington Avenue Baltimore, MD 21202 Towson, MD 21204 RE: Baltimore City OIG Case #20-0040-I Baltimore County OIG Case #20-018 Dear Mayor Scott and County Executive Olszewski, In March 2020, the Baltimore City Office of the Inspector General (OIG) and the Baltimore County OIG received a complaint about inaccurate water bills affecting Baltimore City and Baltimore County residents and businesses. In response, the OIGs initiated a joint investigation into aspects of the City’s water billing system. As a result of this investigation, the OIGs are publishing this joint report, which is intended to give an overview of the City’s water billing system and the various issues affecting it. While the OIGs found the issues highlighted in this report constitute waste, the exact amount of waste is difficult to quantify due to the complexities associated with the water billing system. One of these complexities is a cost sharing arrangement between the City and the County. The OIGs estimate that the issues discussed in this report have cost the City and the County millions of dollars in lost water and sewer revenues. Such waste has significant financial implications on the operations and budgets of the two jurisdictions. As detailed in the report, there are two significant findings concerning the City’s water billing system that need to be addressed. -

184 Maryland Historical Magazine Thomas Poppleton’S Map: Vignettes of a City’S Self Image

184 Maryland Historical Magazine Thomas Poppleton’s Map: Vignettes of a City’s Self Image Jeremy Kargon ritten histories of Baltimore often refer to thePlan of the City of Baltimore, published originally in 1823. Typically but imprecisely credited to Thomas WPoppleton, this map illustrated the city plan he produced between 1816 and 1822. City politicians had commissioned a survey just before the War of 1812, but Poppleton began his work in earnest only after the conflict ended. Once adopted, the work determined the direction of Baltimore’s growth until well after the Civil War.1 Although this street layout significantly influenced the city’s nineteenth-cen- tury development, a second feature of this document has also attracted historians of the city’s architecture. The map’s publisher’s arranged thirty-five small engravings around the border of the map illustrating public buildings in use or under construc- tion at the time of the original publication. They gave each illustration a simple title and provided additional descriptive information about the building, including the architect’s name, the building’s date of completion, and the building’s cost. These pictures are a useful record of Baltimore’s earliest significant architecture, particu- larly for those buildings demolished before the age of photography. Historians’ treatments of these images, and of the map itself, have typically looked at these illustrations individually.2 Consideration of their ensemble, on the other hand, provides evidence for discussion of two broader themes, the public’s perception of architecture as a profession and as a source of shared material cul- ture, and the development of that same public’s civic identity as embodied in those buildings. -

Expanding Sector Employment Opportunities for Young Adults in Baltimore

Expanding Sector Employment Opportunities for young adults in Baltimore February 2016 This report was prepared for the Baltimore Workforce Funders Collaborative By Marcia E. Kingslow | Kingslow Associates | kingslow-assoc.com Design: The Hatcher Group | thehatchergroup.com For more information contact: Linda Dworak, Baltimore Workforce Funders Collaborative The Association of Baltimore Area Grantmakers abagrantmakers.org/bwfc 410-727-1205 2 Table of Contents I. Introduction 4 II. Baltimore’s Sector Partnerships and Youth 6 III. Working with Opportunity Youth 11 IV. Employer Receptivity to Hiring Young Adults 19 V. Complementary Approaches to Sector Strategies 22 VI. Lessons from Youth Opportunity Baltimore 25 VII. Recommendations 29 Appendix: List of Key Informants 32 3 I. Introduction The Baltimore Workforce Funders Collaborative (BWFC) has supported a network of industry sector partnerships that to varying degrees have included young adults in their programs. With increased attention being paid to disconnected youth,1 BWFC is in a position to help its partnerships become more intentional about the programs and opportunities it makes available to young adults. Working with Jobs for the Future, BWFC has an opportunity to develop a strategy to connect young adults to sector programs. This would build on a history of implementing innovative youth programs in Baltimore, such the city’s nationally recognized Youth Opportunity Baltimore program,2 which was part of a U.S. Department of Labor demonstration from 2000 to 2006, as well as emerging efforts to spark more collaboration among opportunity youth organizations through the Aspen Institute’s Opportunity Youth Investment Fund (OYIF). These opportunities emerge at a time when Baltimore is refocusing on issues raised in response to the death of Freddie Gray while in police custody. -

JACOB SNIVELY FAMILY HISTORY and BENJAMIN BEAN FAMILY HISTORY

JACOB SNIVELY FAMILY HISTORY and BENJAMIN BEAN FAMILY HISTORY Written by William Bauman C & O Canal Association Volunteer MAY 2017 Jacob Snively Family History PREFACE A table of vital statistics for the Snively family is provided at the end of this story. As subsequent census reports, marriage records, obituaries, draft registration cards, etc., provided different data, the table was revised. This is a work in progress and new information would be most welcome. The John Snavely information came from various sources in Ancestry.com. The name Snively was sometimes spelled Shuebly, Schnebly, Schnebele or Snibly. I have tried to retain the original spelling with the correction in brackets. The use of parenthesis was as in the original article, whereas I have used brackets to provide my comments or clarifications. Because so much of this family history occurred before the Civil War, I have included vignettes of some of the men who interacted with Jacob Snively. If the reader finds that distracting, just skip over those stories. Some vignettes may be hard to read, this is a history. The reader will also note the several times when Jacob Snively’s transactions included relatives. One of the men whose name kept cropping up was that on Benjamin Bean, who owned a hotel and Tavern on Main Street. The Sheriff routinely held Sheriff’s Sales at the Bean house, hotel or Tavern, as it was variously noted. Benjamin Bean was also related to Jacob Snively, by marriage. With only 271 residents in Hancock in 1820, Jacob Snively was related to many of them or had a business relationship. -

Impactreport2018fulldocuments

2018 2018 Board of Directors Susan Scotto Dyckman Jason Bell Timothy M. Hurley Consultant Bell Wealth Nelson Mullins ToolBank President Management Group Riley & Scarborough, ToolBank Staff LLP Dennis Sanschagrin Jeff Braun Noah Smock Structural Group Stanley Black & Decker Abby Jackson Executive Director ToolBank Vice President Johns Hopkins William J. Brown Carey School of Business John Robinson Exelon/ BGE MB Business Credit Barbara Klein Harper ToolBank Treasurer Jeremy Carpenter UPS Information Services Len the Plumber Ashley Van Stone Brian Pham Rachel Thompson Trash Free Maryland Aandria M.E. Carr Break A Difference ToolBank Secretary Consultant Program Manager Matthew Robinson Greg Ferraro Laureate Education Jones Lang LaSalle Vik Subramaniam Steve Galliard Grant Thornton, LLP The Home Depot Flash QA Supervisor Dear Friends, 2018 was a powerful year for the Baltimore Community ToolBank in service to our partners across a diversity of impact areas. As a regional resource, we fueled projects taking place with our blue tools in Baltimore City, Washington, D.C., throughout the state of Mary- land and even in Pennsylvania and New York City! As simple as it is to share tools, equipment and expertise, we know that when we do so we empower our partners to save time and money for their projects. Our service touches change-agents who work to combat some of the most entrenched issues facing our com- munities. Whether it’s a drill in the hand of a volunteer helping build a new school playground or our tables and chairs being used for a community picnic, we are proud to support positive work of all shapes and sizes across a wide spectrum. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1952, Volume 47, Issue No. 1

MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE Fountain Rock, Ringgold Home in Washington County, Later St. James' School MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY BALTIMORE March • 1952 SMITH'S TRADITIONAL BOOK STORE FURNITURE Established 1876 for Homes of Special attention to inquiries DMinBion for books relating to Baltimore and Maryland. Specializing in fine mahogany furniture and custom uphol- stery of authentic designs for LIBRARIES OR SINGLE BOOKS PURCHASED every room of your home. FALLON & HELLEN 805 N. HOWARD STREET 11 and 13 W. Mulberry St. Mu 2823 BALTIMORE 1 LExington 3345 Specializing in AMERICANA TONGUE, BROOKS BOOKS ON AMERICAN HISTORY & COMPANY GKNEAIXXiY LOCAL HISTORY BOUGHT AND SOLD INSURANCE CATALOGUES ISSUED <~All Coverages FREE UPON REQUEST 213 Saint Paul Place SOUT11EUIN BOOK CO. Baltimore 6 EAST FRANKLIN STREET BALTIMORE 2, MD. VErnon 8271 sis A sc SZShi-^ MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE PUBLISHED BY THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME XLVII BALTIMORE 1952 H CONTENTS OF VOLUME XLVII PAGE AMELUNG AND HIS BREMEN GLASS WARES. Harriet N. Milford, . 1 THE GREAT BALTIMORE WHIG CONVENTION OF 1840. Robert Gray Gunderson, 11 FOUNTAIN ROCK, THE RINGGOLD HOME IN WASHINGTON COUNTY. Edith Rossiter Bevan, 19 THE FREEDMEN'S BUREAU AND EDUCATION IN MARYLAND. W. A. Low, 29 THE CITY HALL, BALTIMORE. Bernard B. Perlman, 40 MARYLAND BIBLIOGRAPHY: 1951, 55 REVIEWS OF RECENT BOOKS, 62, 146, 245, 340 NOTES AND QUERIES, 84, 166, 264, 354 JOHN GRUBER AND HIS ALMANAC. Dieter Cunz, 89 AN ENGLISHMAN IN THE FRENCH ARMY IN AMERICA, 1755. Edited by James High, 103 COURT SQUARE, FREDERICK. Charles McC. Mathias, Jr., 110 FRIENDSHIP VALLEY FARM. Ruth Gist Pickens 121 THOMAS JOHN CLAGGETT: ARREST AND IMPRISONMENT, 1861-62. -

Community Resources Guide, Karl Weber and Thank You to Those Who Have Contributed As a Sponsor

Baltimore County 410-887-2594 Maryland Relay - 7-1-1 Baltimore County Executive John A. Olszewski, Jr. and the County Council Maryland Access Point Information, Assistance and Options Counseling For Older Adults and Persons with Disabilities www.baltimorecountymd.gov/Aging Compassion • Excellence • Dignity Answers for the Aging A FREE telephone-based information and referral service for older adults and caregivers. 667-600-2100 or toll free 1-888-502-7587 (Maryland only) Inspired by the Gospel mandates to love, serve and teach, cc-md.org/afa Catholic Charities provides care and services to improve the lives of Marylanders in need. [email protected] Catholic Charities welcomes people regardless of faith and is an Equal Housing Opportunity provider. 2 Community Resources | 2019 Baltimore County 410-887-2594 MESSAGE FROM THE BALTIMORE COUNTY EXECUTIVE Maryland Relay - 7-1-1 As I begin my duties as County Executive, it is my pleasure to support the tradition of providing resources to Baltimore County citizens. Community Resources 2019 represents one of those resources. I take pride in knowing that the 22nd edition of Community Resources continues to provide vital information about the services and resources that support our families, loved ones and friends. This year, we are pleased to continue our Department of Aging’s collaboration with the Baltimore County Department of Planning and the Commission on Disabilities as partners and contributors to this annual publication. This edition of Community Resources celebrates the seventh year that Baltimore County and Baltimore City Governments have partnered to create a regional resource directory to serve all of Baltimore’s citizens. -

Blockbusting in Baltimore: the Edmondson Village Story

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 9-30-1994 Blockbusting in Baltimore: The Edmondson Village Story W. Edward Orser Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Orser, W. Edward, "Blockbusting in Baltimore: The Edmondson Village Story" (1994). United States History. 8. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/8 Blockbusting in Baltimore This page intentionally left blank Blockbusting in Baltimore THE EDMONDSON VILLAGE STORY W. EDWARD ORSER THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this book was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities Copyright © 1994 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 07 06 05 04 03 6 543 2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Orser, W. Edward Blockbusting in Baltimore: the Edmondson Village story / W. Edward Orser p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8131-0935-3 (pbk.) 1. -

FILE NAME/TOPIC SUBJECT MATTER AAI Corporation Academy Heights (Community) Adams Express Company Administrative Officer Baltimo

Vertical File Collection Historical Society of Baltimore County FILE NAME/TOPIC SUBJECT MATTER AAI Corporation Academy Heights (community) Adams Express Company Administrative Officer Baltimore Co Government Aero Acres (community) Affinity (BA-0384) African American History: Maryland African-American Schools African-American Communities & Sites African-American History African-American History: Baltimore County Agiburth (community) Aging Department Baltimore Co Government Agricultural Center Baltimore County Agricultural Center of Baltimore County Agriculture (generally) Aigburth Manor (Aigburth Vale; BA-0100) Alberton Mills Alberton Estate Alex Brown & Sons All Saints (convent) Churches All Saints (Episcopal; BA-1262, -1375, -1377) Churches Almony's Tavern (BA-0393) Almshouse: Baltimore County Almshouses (generally) American Red Cross Amusement Parks Andor Farm (BA-0113) Annandale (BA-0688) Anne Arundel County Anneslie (community) Anneslie (historic house; BA-0101) Annunciation Cathedral (Greek Orthodox) Churches Arbutus (community) Arbutus Farm (Manual Labor School) Schools Archeology Archeology: Baltimore County Architecture Armagh Village (community) Arnolia (United Methodist) Churches Asbury (United Methodist; BA-0357) Churches Asbury Chapel (BA-1230) Churches File sizes may vary dramatically. www.hsobc.org Page 1 Vertical File Collection Historical Society of Baltimore County FILE NAME/TOPIC SUBJECT MATTER Ascension Schools Ashland (historic community; BA-2952) Ashland (Presbyterian; BA-0201) Churches Ashland Iron Works (BA-0191) -

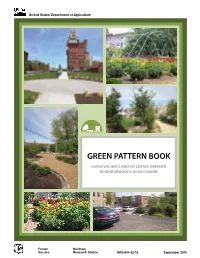

Green Pattern Book Using Vacant Land to Create Greener Neighborhoods in Baltimore

United States Department of Agriculture GROWING GREEN INITIATIVE GREEN PATTERN BOOK USING VACANT LAND TO CREATE GREENER NEIGHBORHOODS IN BALTIMORE Forest Northern Service Research Station NRS-INF-32-15 September 2015 Cover photos by, clockwise from top left: Amy Gilder-Busatti, Baltimore City, used with permission; Miriam Avins, Baltimore Green Space, used with permission; Mark Cameron, Baltimore City, used with permission; Mark Cameron, Baltimore City, used with Abstract permission; Miriam Avins, Baltimore Green Space, used with permission; Mark Cameron, Baltimore City, used with permission This document serves as a tool to assist the City of Baltimore’s residents, administration, and community and nongovernmental organizations in “greening” the vacant land and improving the quality of life in the city. There are about 14,000 vacant lots in Bal- timore, and an estimated 16,000 abandoned houses. While these vacant properties can be a prob- lem, they also offer an opportunity to create greener neighborhoods. Baltimore’s Growing Green Initia- tive, which began in 2014, was de- veloped to improve collaboration, develop procedures, and provide support and assistance to groups working toward a sustainable, green future for Baltimore. Here we classify the types of vacant land, describe eight different ‘greening’ patterns, and provide descriptions and photos of successful efforts. How to cite this publication: Baltimore Department of Planning, Office of Sustainability. 2015. Green pattern book: using vacant land to create greener neighborhoods in Baltimore. NRS-INF-32-15. Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station. 109 p. Published by: This document is available at: : U.S.