Blockbusting in Baltimore: the Edmondson Village Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 099 261 SO 007 956 TITLE Urban

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 099 261 SO 007 956 TITLE Urban Growth: Today's Challenge. Seventh Grade, Social Studies. INSTITUTION Baltimore City Public Schools, Md. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 180p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$9.00 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *City Planning; Curriculum Guides; Discovery Learning; Educational Objectives; Fundamental Concepts; Grade 7; *Human Geography; Inquiry Training; Interdisciplinary Approach; Learning Activities; Resource Materials; Skill Development; *Social Studies; *Urbanization; *Urban Studies IDENTIFIERS Baltimore; Maryland ABSTRACT This course of study offers to seventh grade pupils themes which are designed to clarify the meaning and importance of the urban environment in which they live. The guide is about people in the cities and about the planning, growth, and problems of cities. Themes cover the Baltimore city area, urbanization in Maryland, urbanization in the United States, and urbanization in the world. The disciplines of history, economics, geography, political science, sociology, and anthropology are woven into the content and learning activities. Techniques of discovery and inquiry are recommended. Specific learning experiences provide opportunities for theuse of skills in a functional manner. A selected bibliography on city, state, and federal relationships in government; a list of selected nonprint media on city, state, and federal relationships; and an annotated bibliography replace the use of a single textbook. Each of the four themes in introduced; has a list of objectives; and has schematically related content, understandings and generalizations, sample activities, and suggested skills. (Author/KSM) V 66616,...`5. r Nir -r&,.vttfh, , a 4 66 466 116 . c .7 a.:A '... i d ' 40114 t , yt? , ,V., t ,;..A 4 .4 .1.1 '''"('''' :PAT't.pr' '1. -

Entire Public Libraries Directory In

October 2021 Directory Local Touch Global Reach https://directory.sailor.lib.md.us/pdf/ Maryland Public Library Directory Table of Contents Allegany County Library System........................................................................................................................1/105 Anne Arundel County Public Library................................................................................................................5/105 Baltimore County Public Library.....................................................................................................................11/105 Calvert Library...................................................................................................................................................17/105 Caroline County Public Library.......................................................................................................................21/105 Carroll County Public Library.........................................................................................................................23/105 Cecil County Public Library.............................................................................................................................27/105 Charles County Public Library.........................................................................................................................31/105 Dorchester County Public Library...................................................................................................................35/105 Eastern -

Michigan Land Contract Guide Important Disclaimer: The

Michigan Land Contract Guide Important Disclaimer: The information in this guide is meant to be educational and general in nature. It does not replace the advice of an attorney. Why a Land Contract Guide Now? One of the impacts of the foreclosure crisis has been the increase in the use of land contracts as a way to buy or sell a home. A land contract can provide a way for a homebuyer who cannot qualify for conventional financing to purchase a home. It can also provide a way for seller to be more likely to sell a home and sell it at a price closer to its perceived value than an appraisal would reflect. While a land contract can be a viable and valuable alternative to traditional financing, it can also cause significant problems for both buyers and sellers who do not understand the basics and who enter into a poorly crafted contract. The purpose of this guide is to provide those basics and a check list of those considerations and provisions that make for a well-crafted Land Contract in the state of Michigan. It does not replace the advice of an attorney. What is a Land Contract? A land contract is an agreement between a buyer and a seller that states the buyer is purchasing property but will not receive the legal title until the debt has been satisfied. Land contracts are a form of seller financing and are typically used in real estate transactions, usually residential, when a buyer cannot secure traditional means of financing . Unlike a mortgage, a land contract stipulates that if a buyer does not fulfill his financial obligations in the agreed upon terms of the contract, then the seller regains possession of the property and keeps whatever money the buyer has remitted. -

Green V. Garrett: How the Economic Boom of Professional Sports Helped to Create, and Destroy, Baltimore's

Green v. Garrett: How the Economic Boom of Professional Sports Helped to Create, and Destroy, Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium 1953 Renovation and upper deck construction of Memorial Stadium1 Jordan Vardon J.D. Candidate, May 2011 University of Maryland School of Law Legal History Seminar: Building Baltimore 1 Kneische. Stadium Baltimore. 1953. Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore. Courtesy of Enoch Pratt Free Library, Maryland’s State Library Resource Center, Baltimore, Maryland. Table of Contents I. Introduction........................................................................................................3 II. Historical Background: A Brief History of the Location of Memorial Stadium..............................................................................................................6 A. Ednor Gardens.............................................................................................8 B. Venable Park..............................................................................................10 C. Mount Royal Reservoir..............................................................................12 III. Venable Stadium..............................................................................................16 A. Financial History of Venable Stadium.......................................................19 IV. Baseball in Baltimore.......................................................................................24 V. The Case – Not a Temporary Arrangement.....................................................26 -

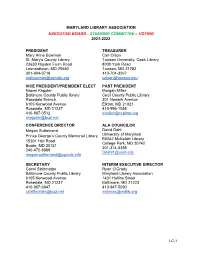

MLA Organizational Structure

MARYLAND LIBRARY ASSOCIATION EXECUTIVE BOARD - STEERING COMMITTEE – VOTING 2021-2022 PRESIDENT TREASURER Mary Anne Bowman Carl Olson St. Mary’s County Library Towson University, Cook Library 23630 Hayden Farm Road 8000 York Road Leonardtown, MD 20650 Towson, MD 21252 301-904-0718 410 - 704 - 3267 [email protected] [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT/PRESIDENT ELECT PAST PRESIDENT Naomi Keppler Morgan Miller Baltimore County Public library Cecil County Public Library Rosedale Branch 301 Newark Avenue 6105 Kenwood Avenue Elkton, MD 21921 Rosedale, MD 21237 410 - 996 - 1055 410-887-0512 [email protected] [email protected] CONFERENCE DIRECTOR ALA COUNCILOR Megan Sutherland David Dahl Prince George’s County Memorial Library University of Maryland B0242 McKeldin Library 15301 Hall Road College Park, MD 20742 Bowie, MD 20721 301-314-0395 240-472-8889 [email protected] [email protected] SECRETARY INTERIM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Conni Strittmatter Ryan O’Grady Baltimore County Public Library M ary land Library Association 6105 Kenwood Avenue 1401 Hollins Street Rosedale, MD 21237 Baltimore, MD 21223 410-887-6047 410 - 947 - 5090 [email protected] [email protected] I-C-1 EXECUTIVE BOARD – APPOINTED OFFICERS - VOTING 2021-2022 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT LEGISLATIVE Tyler Wolfe Andrea Berstler Baltimore County Public Library Carroll County Public Library 3202 Bayonne Avenue 1100 Green Valley Road Baltimore, MD 21214 New Windsor, MD 21776 410-905-6866 443-293-3136 cell: 443-487-1716 [email protected] [email protected] INTELLECTUAL FREEDOM Andrea -

Installment Land Contracts: Developing Law in Virginia

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 37 | Issue 4 Article 8 Fall 9-1-1980 Installment Land Contracts: Developing Law in Virginia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons, and the Secured Transactions Commons Recommended Citation Installment Land Contracts: Developing Law in Virginia, 37 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 1161 (1980), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol37/iss4/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Notes INSTALLMENT LAND CONTRACTS: DEVELOPING LAW IN VIRGINIA An installment land sale contract1 is a method of seller financing for land sales. The land contract, sometimes referred to as a "contract for deed" or "longterm contract," functions as a substitute for a mortgage or deed of trust.2 Generally, in a mortgage, the seller conveys title to the property, and the buyer obtains financing by pledging the property as security for the purchase price of the land.3 The mortgagee has a lien on the buyer's title.4 In a deed of trust transaction, the buyer conveys title to the property to a third party to hold as trustee during the period of in- debtedness. 5 In a land contract, the seller finances the land sale retaining legal title to the property until the buyer makes the final installment payment.e Land contracts are used most often in states in which- mortgage law heavily favors the mortgagor.7 Pro-mortgagor law restricts the mortga- gee's right to enforce the lien on the property by prescribing lengthy pro- cedures for mortgage foreclosure.8 Sellers often prefer land contracts be- ' G. -

Ethno-Racial Attitudes and Social Inequality Editor's Proof

Editor's Proof Ethno-Racial Attitudes and Social Inequality 22 Frank L. Samson and Lawrence D. Bobo 1 Introduction (1997)). Within psychology we have seen an ex- 22 plosion of work on implicit attitudes or uncon- 23 2 Sociologists ordinarily assume that social struc- scious racism that more than ever centers atten- 24 3 ture drives the content of individual level values, tion on the internal psychological functioning of 25 4 attitudes, beliefs, and ultimately, behavior. In the individual. We argue here that, in general, a 26 5 some classic models this posture reaches a point committed social psychological posture that ex- 27 6 of essentially denying the sociological relevance amines both how societal level factors and pro- 28 7 of any micro-level processes. In contrast, psy- cesses shape individual experiences and outlooks 29 8 chologists (and to a degree, economists) operate and how the distribution of individual attitudes, 30 9 with theoretical models that give primacy to in- beliefs, and values, in turn, influence others and 31 10 dividual level perception, cognition, motivation, the larger social environment provides the fullest 32 11 and choice. Within the domain of studies of ethno- leverage on understanding the dynamics of race. 33 12 racial relations, each of these positions has mod- Specifically we argue in this chapter that ethno-ra- 34 13 ern advocates. From the sociologically determin- cial attitudes, beliefs, and identities play a funda- 35 14 istic vantage point Edna Bonacich trumpets the mental constitutive role in the experience, re-pro- 36 15 “‘deeper’ level of reality” exposed by class ana- duction, and process of change in larger societal 37 16 lytics (1980, p. -

Land Contracts Presentation FINAL

Annette Higby, Emma Hempstead, Thomas Bell Other names: Installment Land Contract, Contract for Deed, etc. Buyer Regular Principal and Interest Payments § Usually annual § To the Seller Takes possession of property at outset of contract Seller Retains title until all payments made May retain possessory interest in some of the property Buyer Able to possess land without access to commercial credit No significant down payment Seller Simple means of transferring farmland Ease tax consequences into installments Greater pool of potential buyers Can retain a life estate in the homestead Buyer Forfeiting possession in default Forfeiting payments made in default Seller Buyer default Decline in land values Waste Bankruptcy of Buyer High risk of default, Buyer often ineligible for commercial or FSA lending Nearly all land contracts protect the Seller with a forfeiture clause If Buyer defaults on a payment they forfeit possession of property, and all payments made to date Sometimes considered a form of liquidated damages can become unreasonable, especially when buyer has: made most of the contract payments, or made significant improvements to the farm prior to default Varies greatly by jurisdiction Enforce forfeiture clause but require Seller provide brief right to cure and a right of redemption upon full payment of the contract (Maine) Restitution theory requiring Seller to return any payments beyond Seller’s actual damages Rental theory of damages Fair market value of land at time of default in relation to contract price (New Hampshire) Restatement of Property §3.4(a) regards the land contract as a mortgage, and Seller’s remedy is foreclosure. Foreclosure sale price determines duties, if in excess of the contract Buyer receives payment, if less than contract price, Seller has a right to the deficiency. -

The Future Looks Bright

The Future Looks Bright Main Line companies look to schools to build workforce of tomorrow “Trekkies” Take Flight Inside Lower Merion High School’s international service trips Look Inside What’s happening at top Main Line private schools? Dining & Shopping l Schools & Colleges l Cultural Attractions Local Entertainment & Activities l Health & Medical The Main Line Chamber of Commerce Look inside for The Main Line Chamber of Commerce directory West Laurel Hill One Call To One Place - For Everything We plan for just about every event in life except for the one certainty. Contact us to get started. Pre-Planning available for: M Cemetery Property & Merchandise 610.668.9900 M Funeral Arrangements www.WestLaurelHill.com M Cremation Arrangements 225 Belmont Ave M Jewish & Green Services Bala Cynwyd, PA M Monument Design William A. Sickel, F.D., Supervisor, West Laurel Hill Funeral Home, Inc. 2 • Guide to the Main Line 2017/2018 mainlinemedianews.com mainlinemedianews.com Guide to the Main Line 2017/2018 • 3 Welcome to the Table of Contents Departments WE KNOW KITCHENS. Business/Financial Services ............................. 46 Let us help you find the right ingredients. Main Line Dining. .............................................................. 64 Shopping .......................................................... 73 Education ......................................................... 81 Senior Services. ................................................ 93 Health and Wellness -

Racial Cartels

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 16 2010 Racial Cartels Daria Roithmayr University of Southern California Gould School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Law and Race Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Daria Roithmayr, Racial Cartels, 16 MICH. J. RACE & L. 45 (2010). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol16/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACIAL CARTELS Daria Roithmayr* This Article argues that we can better understand the dynamic of historical racial exclusion if we describe it as the anti-competitive work of "racial cartels." We can define racial cartels to include a range of all-White groups-homeowners' associations, school districts, trade unions, real estate boards and political parties- who gained signficant social, economic and political profit from excluding on the basis of race. Farfrom operating on the basis of irrational animus, racial cartels actually derived significant profit from racial exclusion. By creating racially segmented housing markets, for example, exclusive White homeowners' associations enjoyed higher property values that depended not just on the superior quality of the housing stock but also on the racial composition of the neighborhood. -

2019 12 18 Pickett V Cleveland Complaint

Case: 1:19-cv-02911 Doc #: 1 Filed: 12/18/19 1 of 39. PageID #: 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO EASTERN DIVISION ALBERT PICKETT, JR., KEYONNA Case No. JOHNSON, JAROME MONTGOMERY, ODESSA PARKS, and TINIYA SHEPHERD Judge: (f/k/a TINIYA HALL), on behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated, CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Plaintiffs, Jury Trial Demanded v. CITY OF CLEVELAND, Defendant. Plaintiffs Albert Pickett, Jr., Keyonna Johnson, Jarome Montgomery, Odessa Parks, and Tiniya Shepherd (f/k/a Tiniya Hall), on behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated (collectively, “Plaintiffs”), bring this civil rights class action seeking to remedy Defendant City of Cleveland’s (“Cleveland” or “the City”) violations of the Fair Housing Act (“FHA”), 42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 et seq.; the U.S. Constitution, Amendment XIV, brought under 42 U.S.C. § 1983; the Ohio Constitution, Article I, § XVI; and the Ohio Civil Rights Act, Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 4112.02(H). PRELIMINARY STATEMENT 1. Water is life: it is essential for health, hygiene, cooking, and cleaning. In and around Cleveland, however, water has put residents—disproportionately those who are Black—at risk of losing their homes due to the City’s draconian policy of placing liens on properties with overdue water bills. The lack of water—through unaffordable and often erroneous bills that lead to rampant service shutoffs—also impacts thousands of Cleveland residents every year. 1 Case: 1:19-cv-02911 Doc #: 1 Filed: 12/18/19 2 of 39. PageID #: 2 2. Black residents of Cleveland have faced housing challenges for decades. -

Right to Housing

THE RIGHT TO HOUSING If a person has a low opinion of himselfand is unhappy because he lives in a filthy, dilapidated,rat-infested house, you cannot tell him to apply positive thinking-and "Be Happy!" Happiness will begin to blossom only when he finds a way to get out of his physical trap into improved surroundings. Harold Cruse* I. INTRODUCTION Housing is basic to human survival. When properly constructed and maintained, it provides an essential element for life: shelter from the forces of nature. The 1949 Housing Act' recognized the importance of housing by enunciating the national goal of a "decent home and a suitable living envi- ronment for every American family." The impact of housing quality on so- cietal well being is undeniable. For example, the quality and character of the family living unit significantly affects the nature of organized family life.2 Moreover, poor housing has been shown to cause mental and physical illness and is a contributing factor to the cause of crime.3 The demonstrated importance of housing quality supports the assertion that the right to habitable housing is a personal interest which is "implicit in the concept of ordered liberty"4 and thereby deserving of constitutional pro- tection. Yet, in Lindsey v. Normet5 the Supreme Court held that access to housing of a particular quality is not a fundamental interest which requires application of a strict standard of review under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Thus, governmental action which curtails a person's ability to obtain habitable housing need only bear a rational rela- tionship to a permissible governmental objective.6 Because the range of per- missible governmental objectives is broad, a rational relationship can usually be established and a challenged governmental action upheld.7 * H.