FWS-R2-ES-2017-0018 US Fish and Wildlife MS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revision of Karst Species Zones for the Austin, Texas, Area

FINAL REPORT As Required by THE ENDANGERED SPECIES PROGRAM TEXAS Grant No. E - 52 Endangered and Threatened Species Conservation REVISION OF KARST SPECIES ZONES FOR THE AUSTIN, TEXAS, AREA Prepared by: George Veni Robert Cook Executive Director Matt Wagner Mike Berger Program Director, Wildlife Diversity Division Director, Wildlife 3 October 2006 FINAL REPORT STATE: ____Texas_______________ GRANT NUMBER: ___E - 52____________ GRANT TITLE: Revision of Karst Species Zones for the Austin, Texas Area REPORTING PERIOD: ____1 September 2004 to 31 August 2006 OBJECTIVE: To re-evaluate and redraw, as necessary and in a GIS, all four karst zones within the twenty-two 7.5’ topographic quadrangle area as defined by Veni and Associates (1992). SEGMENT OBJECTIVE: 1. Re-evaluate and re-draw, as necessary and into a Geographic Information System (GIS), all four karzt zones within the twenty-two 7.5’ topographic quadrangle area as defined by Veni and Associates (1992) within six (6) months of contract award date. SIGNIFICANT DEVIATION: None. SUMMARY OF PROGRESS: Please see Attachment A. LOCATION: Austin Area, Texas. PREPARED BY: ___Craig Farquhar______ DATE: October 3, 2006 APPROVED BY: _____________________ DATE: October 10, 2006 Neil (Nick) E. Carter Federal Aid Coordinator 2 George Veni & Associates Hydrogeologists and Biologists Environmental Management Consulting Cave and Karst Specialists REVISION OF KARST SPECIES ZONES FOR THE AUSTIN, TEXAS, AREA by George Veni, Ph.D., and Cecilio Martinez prepared for: Texas Parks and Wildlife Department 4200 -

Comal County Regional Habitat Conservation Plan Environmental Impact Statement

Draft Comal County Regional Habitat Conservation Plan Environmental Impact Statement Prepared for: Comal County, Texas Comal County Commissioners Court Prepared by: SWCA Environmental Consultants Smith, Robertson, Elliott, Glen, Klein & Bell, L.L.P. Prime Strategies, Inc. Texas Perspectives, Inc. Capital Market Research, Inc. April 2010 SWCA Project Number 12659-139-AUS DRAFT COMAL COUNTY REGIONAL HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT April 2010 Type of Action: Administrative Lead Agency: U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Responsible Official: Adam Zerrenner Field Supervisor U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 10711 Burnet Road, Suite 200 Austin, Texas For Information: Bill Seawell Fish and Wildlife Biologist U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 10711 Burnet Road, Suite 200 Austin, Texas Tele: 512-490-0057 Abstract: Comal County, Texas, is applying for an incidental take permit (Permit) under section 10(a)(1)(B) of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended 16 U.S.C. § 1531, et seq. (ESA), to authorize the incidental take of two endangered species, the golden-cheeked warbler (Dendroica chrysoparia) and the black-capped vireo (Vireo atricapilla), referred to collectively as the “Covered Species.” In support of the Permit application, the County has prepared a regional habitat conservation plan (Proposed RHCP), covering a 30-year period from 2010 to 2040. The Permit Area for the Proposed RHCP and the area of potential effect for this Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) is Comal County in central Texas. The requested Permit would authorize the following incidental take and mitigation for the golden-cheeked warbler: Take: As conservation credits are created through habitat preservation, authorize up to 5,238 acres (2,120 hectares) of golden-cheeked warbler habitat to be impacted over the 30-year life of the Proposed RHCP. -

Petition to Delist the Bone Cave Harvestman (Texella Reyesi) in Accordance with Section 4 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973

Petition to delist the Bone Cave harvestman (Texella reyesi) in accordance with Section 4 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 PETITION TO DELIST THE BONE CAVE HARVESTMAN (TEXELLA REYESI) IN ACCORDANCE WITH SECTION 4 OF THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT OF 1973 Petitioned By: John F. Yearwood Kathryn Heidemann Charles & Cheryl Shell Walter Sidney Shell Management Trust American Stewards of Liberty Steven W. Carothers June 02, 2014 This page intentionally left blank. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The federally endangered Bone Cave harvestman (Texella reyesi) is a terrestrial karst invertebrate that occurs in caves and voids north of the Colorado River in Travis and Williamson counties, Texas. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) listed T. reyesi as endangered in 1988 on the basis of only five to six known localities that occurred in a rapidly developing area. Little was known about the species at the time, but the USFWS deemed listing was warranted to respond to immediate development threats. The current body of information on T. reyesi documents a much broader range of known localities than known at the time of listing and resilience to the human activities that USFWS deemed to be threats to the species. Status of the Species • An increase in known localities from five or six at the time of listing to 172 today. • Significant conservation is in place with at least 94 known localities (55 percent of the total known localities) currently protected in preserves, parks, or other open spaces. • Regulatory protections are afforded to most caves in Travis and Williamson counties via state laws and regulations and local ordinances. -

Karst Invertebrates Taxonomy

Endangered Karst Invertebrate Taxonomy of Central Texas U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Austin Ecological Services Field Office 10711 Burnet Rd. Suite #200 Austin, TX 78758 Original date: July 28, 2011 Revised on: April 4, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 ENDANGERED KARST INVERTEBRATE TAXONOMY ................................................. 1 2.1 Batrisodes texanus (Coffin Cave mold beetle) ......................................................................... 2 2.2 Batrisodes venyivi (Helotes mold beetle) .................................................................................. 3 2.3 Cicurina baronia (Robber Baron Cave meshweaver) ............................................................... 4 2.4 Cicurina madla (Madla Cave meshweaver) .............................................................................. 5 2.5 Cicurina venii (Braken Bat Cave meshweaver) ........................................................................ 6 2.6 Cicurina vespera (Government Canyon Bat Cave meshweaver) ............................................. 7 2.7 Neoleptoneta microps (Government Canyon Bat Cave spider) ................................................ 8 2.8 Neoleptoneta myopica (Tooth Cave spider) .............................................................................. 9 2.9 Rhadine exilis (no common name) ......................................................................................... -

Biodiversity from Caves and Other Subterranean Habitats of Georgia, USA

Kirk S. Zigler, Matthew L. Niemiller, Charles D.R. Stephen, Breanne N. Ayala, Marc A. Milne, Nicholas S. Gladstone, Annette S. Engel, John B. Jensen, Carlos D. Camp, James C. Ozier, and Alan Cressler. Biodiversity from caves and other subterranean habitats of Georgia, USA. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, v. 82, no. 2, p. 125-167. DOI:10.4311/2019LSC0125 BIODIVERSITY FROM CAVES AND OTHER SUBTERRANEAN HABITATS OF GEORGIA, USA Kirk S. Zigler1C, Matthew L. Niemiller2, Charles D.R. Stephen3, Breanne N. Ayala1, Marc A. Milne4, Nicholas S. Gladstone5, Annette S. Engel6, John B. Jensen7, Carlos D. Camp8, James C. Ozier9, and Alan Cressler10 Abstract We provide an annotated checklist of species recorded from caves and other subterranean habitats in the state of Georgia, USA. We report 281 species (228 invertebrates and 53 vertebrates), including 51 troglobionts (cave-obligate species), from more than 150 sites (caves, springs, and wells). Endemism is high; of the troglobionts, 17 (33 % of those known from the state) are endemic to Georgia and seven (14 %) are known from a single cave. We identified three biogeographic clusters of troglobionts. Two clusters are located in the northwestern part of the state, west of Lookout Mountain in Lookout Valley and east of Lookout Mountain in the Valley and Ridge. In addition, there is a group of tro- globionts found only in the southwestern corner of the state and associated with the Upper Floridan Aquifer. At least two dozen potentially undescribed species have been collected from caves; clarifying the taxonomic status of these organisms would improve our understanding of cave biodiversity in the state. -

A Biodiversity and Conservation Assessment of the Edwards Plateau Ecoregion

A Biodiversity and Conservation Assessment of the Edwards Plateau Ecoregion June 2004 © The Nature Conservancy This document may be cited as follows: The Nature Conservancy. 2004. A Biodiversity and Conservation Assessment of the Edwards Plateau Ecoregion. Edwards Plateau Ecoregional Planning Team, The Nature Conservancy, San Antonio, TX, USA. Acknowledgements Jasper, Dean Keddy-Hector, Jean Krejca, Clifton Ladd, Glen Longley, Dorothy Mattiza, Terry The results presented in this report would not have Maxwell, Pat McNeal, Bob O'Kennon, George been possible without the encouragement and Ozuna, Jackie Poole, Paula Power, Andy Price, assistance of many individuals and organizations. James Reddell, David Riskind, Chuck Sexton, Cliff Most of the day-to-day work in completing this Shackelford, Geary Shindel, Alisa Shull, Jason assessment was done by Jim Bergan, Bill Carr, David Singhurst, Jack Stanford, Sue Tracy, Paul Turner, O. Certain, Amalie Couvillion, Lee Elliott, Aliya William Van Auken, George Veni, and David Wolfe. Ercelawn, Mark Gallyoun, Steve Gilbert, Russell We apologize for any inadvertent omissions. McDowell, Wayne Ostlie, and Ryan Smith. Finally, essential external funding for this work This project also benefited significantly from the came from the Department of Defense and the U. S. involvement of several current and former Nature Army Corps of Engineers through the Legacy Grant Conservancy staff including: Craig Groves, Greg program. Without this financial support, many of the Lowe, Robert Potts, and Jim Sulentich. Thanks for critical steps in the planning process might not have the push and encouragement. Our understanding of ever been completed. Thank you. the conservation issues important to the Edwards Plateau was greatly improved through the knowledge and experiences shared by many Conservancy staff including Angela Anders, Gary Amaon, Paul Barwick, Paul Cavanagh, Dave Mehlman, Laura Sanchez, Dan Snodgrass, Steve Jester, Bea Harrison, Jim Harrison, and Nurani Hogue. -

Fifty Years of Cave Arthropod Sampling: Techniques and Best Practices J

International Journal of Speleology 48 (1) 33-48 Tampa, FL (USA) January 2019 Available online at scholarcommons.usf.edu/ijs International Journal of Speleology Off icial Journal of Union Internationale de Spéléologie Fifty years of cave arthropod sampling: techniques and best practices J. Judson Wynne1*, Francis G. Howarth2, Stefan Sommer1, and Brett G. Dickson3 1Department of Biological Sciences, Merriam-Powell Center for Environmental Research, Northern Arizona University, Box 5640, Flagstaff, Arizona 86011, USA 2Department of Natural Sciences, Bernice P. Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice St., Honolulu, Hawaii, 96817, USA 3Conservation Science Partners, 11050 Pioneer Trail, Suite 202, Truckee, CA 96161 and Lab of Landscape Ecology and Conservation Biology, Landscape Conservation Initiative, Northern Arizona University, Box 5694, Flagstaff, Arizona 86011, USA Abstract: Ever-increasing human pressures on cave biodiversity have amplified the need for systematic, repeatable, and intensive surveys of cave-dwelling arthropods to formulate evidence-based management decisions. We examined 110 papers (from 1967 to 2018) to: (i) understand how cave-dwelling invertebrates have been sampled; (ii) provide a summary of techniques most commonly applied and appropriateness of these techniques, and; (iii) make recommendations for sampling design improvement. Of the studies reviewed, over half (56) were biological inventories, 43 ecologically focused, seven were techniques papers, and four were conservation studies. Nearly one-half (48) of the papers applied systematic techniques. Few papers (24) provided enough information to repeat the study; of these, only 11 studies included cave maps. Most studies (56) used two or more techniques for sampling cave-dwelling invertebrates. Ten studies conducted ≥10 site visits per cave. The use of quantitative techniques was applied in 43 of the studies assessed. -

Heritage Oaks Karst Investigation Report

Endangered Karst Invertebrate Impacts Assessment and Proposed Pre-Enforcement Settlement Terms for the Heritage Oaks Subdivision, Georgetown, Texas Prepared for Shel-Jenn, Incorporated Prepared by SWCA Environmental Consultants September 2012 SWCA Project Number 23820 Endangered Karst Invertebrate Impacts Assessment and Proposed Pre-Enforcement Settlement Terms for the Heritage Oaks Subdivision, Georgetown, Texas Introduction Under construction since 2005, the Heritage Oaks residential subdivision in Georgetown, Texas is located north of the intersection of Williams Drive and Shell Road approximately 1.5 miles north of the Lake Georgetown dam. The tract sits roughly on the drainage divide between the North San Gabriel River and Berry Creek and is within the Edwards aquifer recharge zone. It is underlain by Edwards limestone bedrock which is known to be cavernous in the area. Between April and June of 2012 a series of six karst voids were encountered during utility excavation activities. On 25 April 2012, based on information reported to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service by a local resident, the Service issued a letter to Mr. Jimmy Jacobs (President of Shel- Jenn, Incorporated) informing him that Heritage Oaks is located within an area likely to contain endangered karst invertebrate species (Texella reyesi and Batrisodes texanus) and that development activities may be regulated under the Endangered Species Act. In the letter the Field Supervisor of the Austin Ecological Services Office (Adam Zerrenner) advised that incidental take coverage could be provided by either an individual permit or through participation in the Williamson County Regional Habitat Conservation Plan (Wilco RHCP). The Wilco RHCP was approved in 2008 and was not available at the time construction began at Heritage Oaks. -

Chemosystematics in the Opiliones (Arachnida): a Comment on the Evolutionary History of Alkylphenols and Benzoquinones in the Scent Gland Secretions of Laniatores

Cladistics Cladistics (2014) 1–8 10.1111/cla.12079 Chemosystematics in the Opiliones (Arachnida): a comment on the evolutionary history of alkylphenols and benzoquinones in the scent gland secretions of Laniatores Gunther€ Raspotniga,b,*, Michaela Bodnera, Sylvia Schaffer€ a, Stephan Koblmuller€ a, Axel Schonhofer€ c and Ivo Karamand aInstitute of Zoology, Karl-Franzens-University, Universitatsplatz€ 2, 8010, Graz, Austria; bResearch Unit of Osteology and Analytical Mass Spectrometry, Medical University, University Children’s Hospital, Auenbruggerplatz 30, 8036, Graz, Austria; cInstitute of Zoology, Johannes Gutenberg University, Johannes-von-Muller-Weg€ 6, 55128, Mainz, Germany; dDepartment of Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Science, University of Novi Sad, Trg Dositeja Obradovica 2, 2100, Novi Sad, Serbia Accepted 2 April 2014 Abstract Large prosomal scent glands constitute a major synapomorphic character of the arachnid order Opiliones. These glands pro- duce a variety of chemicals very specific to opilionid taxa of different taxonomic levels, and thus represent a model system to investigate the evolutionary traits in exocrine secretion chemistry across a phylogenetically old group of animals. The chemically best-studied opilionid group is certainly Laniatores, and currently available chemical data allow first hypotheses linking the phy- logeny of this group to the evolution of major chemical classes of secretion chemistry. Such hypotheses are essential to decide upon a best-fitting explanation of the distribution of scent-gland secretion -

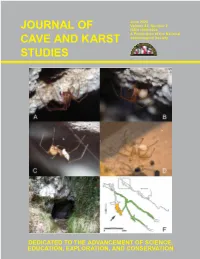

Journal of Cave and Karst Studies

June 2020 Volume 82, Number 2 JOURNAL OF ISSN 1090-6924 A Publication of the National CAVE AND KARST Speleological Society STUDIES DEDICATED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE, EDUCATION, EXPLORATION, AND CONSERVATION Published By BOARD OF EDITORS The National Speleological Society Anthropology George Crothers http://caves.org/pub/journal University of Kentucky Lexington, KY Office [email protected] 6001 Pulaski Pike NW Huntsville, AL 35810 USA Conservation-Life Sciences Julian J. Lewis & Salisa L. Lewis Tel:256-852-1300 Lewis & Associates, LLC. [email protected] Borden, IN [email protected] Editor-in-Chief Earth Sciences Benjamin Schwartz Malcolm S. Field Texas State University National Center of Environmental San Marcos, TX Assessment (8623P) [email protected] Office of Research and Development U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Leslie A. North 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, KY Washington, DC 20460-0001 [email protected] 703-347-8601 Voice 703-347-8692 Fax [email protected] Mario Parise University Aldo Moro Production Editor Bari, Italy [email protected] Scott A. Engel Knoxville, TN Carol Wicks 225-281-3914 Louisiana State University [email protected] Baton Rouge, LA [email protected] Exploration Paul Burger National Park Service Eagle River, Alaska [email protected] Microbiology Kathleen H. Lavoie State University of New York Plattsburgh, NY [email protected] Paleontology Greg McDonald National Park Service Fort Collins, CO The Journal of Cave and Karst Studies , ISSN 1090-6924, CPM [email protected] Number #40065056, is a multi-disciplinary, refereed journal pub- lished four times a year by the National Speleological Society. -

Reprint Covers

TEXAS MEMORIAL MUSEUM Speleological Monographs, Number 7 Studies on the CAVE AND ENDOGEAN FAUNA of North America Part V Edited by James C. Cokendolpher and James R. Reddell TEXAS MEMORIAL MUSEUM SPELEOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS, NUMBER 7 STUDIES ON THE CAVE AND ENDOGEAN FAUNA OF NORTH AMERICA, PART V Edited by James C. Cokendolpher Invertebrate Zoology, Natural Science Research Laboratory Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th Street Lubbock, Texas 79409 U.S.A. Email: [email protected] and James R. Reddell Texas Natural Science Center The University of Texas at Austin, PRC 176, 10100 Burnet Austin, Texas 78758 U.S.A. Email: [email protected] March 2009 TEXAS MEMORIAL MUSEUM and the TEXAS NATURAL SCIENCE CENTER THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN, AUSTIN, TEXAS 78705 Copyright 2009 by the Texas Natural Science Center The University of Texas at Austin All rights rereserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, including electronic storage and retrival systems, except by explict, prior written permission of the publisher Printed in the United States of America Cover, The first troglobitic weevil in North America, Lymantes Illustration by Nadine Dupérré Layout and design by James C. Cokendolpher Printed by the Texas Natural Science Center, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas PREFACE This is the fifth volume in a series devoted to the cavernicole and endogean fauna of the Americas. Previous volumes have been limited to North and Central America. Most of the species described herein are from Texas and Mexico, but one new troglophilic spider is from Colorado (U.S.A.) and a remarkable new eyeless endogean scorpion is described from Colombia, South America. -

What's This Bug?

What’s This Bug? This guide from the Philadelphia Insectarium and Butterfly Pavilion will help identify bugs you might find during your explorations outside. Keep in mind that many of these creatures look different at each life cycle stage. If you can’t identify what you have, you can always email their resident bug expert at [email protected]. Happy trails! In Bush/Trees: Aphid (Aphis spp.) Aphids are small sap-sucking insects and members of the superfamily Aphidoidea. Common names include greenfly and blackfly, although individuals within a species can vary widely in color. The group includes the fluffy white woolly aphids. It reproduces rapidly, often producing live young without mating, and may live in large colonies that cause extensive damage to crops. Asian Lady Beetle (Harmonia axyridis) Harmonia axyridis, most commonly known as the harlequin, multicolored Asian, or Asian ladybeetle, is a large coccinellid beetle. This is one of the most variable species in the world, with an exceptionally wide range of color forms. Native ladybugs look similar except that they do not have the white M-shape at the crown of their “head.” Black Firefly (Lucidota atra) The Black Firefly has light organs, but prefers using aerial pheromones instead of bioluminescence to communicate presence and position. Like all fireflies, Black Fireflies can be found in woodlands, forests, parks, fields, backyards, and in meadows near water. This species prefers areas with moisture and humidity. Black fireflies are more likely to be found in suburbs and rural areas. They tend to avoid city lights. Pale Green Assassin Bug (Zelus luridus) Zelus luridus, also known as the Pale Green Assassin Bug, is a species of assassin bug native to North America.