Narrative Ruses in the Novels of Josã© Rizal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grade 10 Music LM 4

DOWNLOAD K-12 MATERIALS AT DEPED TAMBAYAN20th and 21st Century Multimedia Forms richardrrr.blogspot.com Quarter IV: 20th AND 21st CENTURY MULTIMEDIA FORMS CONTENT STANDARDS The learner demonstrates understanding of... 1. Characteristic features of 20th and 21st century opera, musical play, ballet, and other multi-media forms. 2. The relationship among music, technology, and media. PERFORMANCE STANDARDS The learner... 1. Performs selections from musical plays, ballet, and opera in a satisfactory level of performance. 2. Creates a musical work, using media and technology. DEPEDLEARNING COMPETENCIES COPY The learner... 1. Describes how an idea or story in a musical play is presented in a live performance or video. 2. Explains how theatrical elements in a selected part of a musical play are combined with music and media to achieve certain effects. 3. Sings selections from musical plays and opera expressively. 4. Creates/improvises appropriate sounds, music, gestures, movements, and costumes using media and technology for a selected part of a musical play. 5. Presents an excerpt from a 20th or 21st century Philippine musical and highlights its similarities and differences to other Western musical p l a y s . From the Department of Education curriculum for MUSIC Grade 10 (2014) 141 All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means - electronic or mechanical including photocopying without written permission from the DepEd Central Office. MUSIC Quarter IV OPERA IN THE PHILIPPINES he emergence of the Filipino opera started to take shape during the middle part of Tthe 19th century. Foreign performers, including instrumental virtuosi, as well as opera singers and Spanish zarzuela performers came to the country to perform for enthusiastic audiences. -

Colonial Contractions: the Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946

Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Vicente L. Rafael Subject: Southeast Asia, Philippines, World/Global/Transnational Online Publication Date: Jun 2018 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.268 Summary and Keywords The origins of the Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histories of three empires that swept onto its shores: the Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese. This history makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation- states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power rela tionships. Such shifts have included not just regime change but also social revolution. The modernity of the modern Philippines is precisely the effect of the contradictory dynamic of imperialism. The Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese colonial regimes, as well as their postcolonial heir, the Republic, have sought to establish power over social life, yet found themselves undermined and overcome by the new kinds of lives they had spawned. It is precisely this dialectical movement of empires that we find starkly illumi nated in the history of the Philippines. Keywords: Philippines, colonialism, empire, Spain, United States, Japan The origins of the modern Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histo ries of three empires: Spain, the United States, and Japan. This background makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation-states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power relationships. -

Jose Rizal By: Marilou Diaz Abaya Film Review First, This Movie Is

Jose Rizal by: Marilou Diaz Abaya Film Review First, this movie is rated SPG. There are graphic depictions of violence and even torture. The opening few scenes depict some episodes from Rizal's novels. In one a Catholic priest rapes a Filipina. I guess I now know where the Mestizo (i.e., mixed blood) class came from in the Philippines. In the other scene a Catholic priest beats a child for alleged stealing. Strong thing, and it made me wonder how the Catholic Church could possibly retain any power in the country, if this is what the national hero thought about it. The movie tells the life story of Jose Rizal, the national hero of the Philippines. It covers his life from his childhood to his execution at the hands of the Spanish forces occupying the Philippines in the late 19th century. We are also thrown into the world of Rizal's novels (filmed in black and white), so we get a glimpse of how he viewed Filipino society under the Spanish heal. The movie introduces us to the life of subjugation of the Filipino people under the rule of the Spanish friars. From the execution of three Filipino priests in 1872 for alleged subversion to the harsh and unequal treatment of Filipino students in the schools, this film is a flashing indictment of Spanish colonial rule in the Philippines. We see scenes both from Rizal's actual life but also from his imagination The movie focuses on the condition of the society and also to the government at the time of the Spanish Colonization. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Language, Tagalog Regionalism, and Filipino Nationalism: How a Language-Centered Tagalog Regionalism Helped to Develop a Philippine Nationalism Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/69j3t8mk Author Porter, Christopher James Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Language, Tagalog Regionalism, and Filipino Nationalism: How a Language-Centered Tagalog Regionalism Helped to Develop a Philippine Nationalism A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Southeast Asian Studies by Christopher James Porter June 2017 Thesis Committee: Dr. Hendrik Maier, Chairperson Dr. Sarita See Dr. David Biggs Copyright by Christopher James Porter 2017 The Thesis of Christopher James Porter is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Table of Contents: Introduction………………………………………………….. 1-4 Part I: Filipino Nationalism Introduction…………………………………………… 5-8 Spanish Period………………………………………… 9-21 American Period……………………………………… 21-28 1941 to Present……………………………………….. 28-32 Part II: Language Introduction…………………………………………… 34-36 Spanish Period……………………………………….... 36-39 American Period………………………………………. 39-43 1941 to Present………………………………………... 44-51 Part III: Formal Education Introduction…………………………………………… 52-53 Spanish Period………………………………………… 53-55 American Period………………………………………. 55-59 1941 to 2009………………………………………….. 59-63 A New Language Policy……………………………… 64-68 Conclusion……………………………………………………. 69-72 Epilogue………………………………………………………. 73-74 Bibliography………………………………………………….. 75-79 iv INTRODUCTION: The nation-state of the Philippines is comprised of thousands of islands and over a hundred distinct languages, as well as over a thousand dialects of those languages. The archipelago has more than a dozen regional languages, which are recognized as the lingua franca of these different regions. -

José Rizal and Benito Pérez Galdós: Writing Spanish Identity in Pascale Casanova’S World Republic of Letters

José Rizal and Benito Pérez Galdós: Writing Spanish Identity in Pascale Casanova’s World Republic of Letters Aaron C. Castroverde Georgia College Abstract: This article will examine the relationship between Casanova’s World Republic of Letters and its critical importance, demonstrating the false dilemma of anti-colonial resistance as either a nationalist or cosmopolitan phenomenon. Her contribution to the field gives scholars a tool for theorizing anti-colonial literature thus paving the way for a new conceptualization of the ‘nation’ itself. As a case study, we will look at the novels of the Filipino writer José Rizal and the Spanish novelist Benito Pérez Galdós. Keywords: Spain – Philippines – José Rizal – Benito Pérez Galdós – World Literature – Pascale Casanova. dialectical history of Pascale Casanova’s ideas could look something like this: Her World Republic of Letters tries to reconcile the contradiction between ‘historical’ (i.e. Post-colonial) reading of literature with the ‘internal’ or A purely literary reading by positing ‘world literary space’ as the resolution. However, the very act of reflecting and speaking of the heterogeneity that is ‘world’ literature (now under the aegis of modernity, whose azimuth is Paris) creates a new gravitational orbit. This synthesis of ‘difference’ into ‘identity’ reveals further contradictions of power and access, which in turn demand further analysis. Is the new paradigm truly better than the old? Or perhaps a better question would be: what are the liberatory possibilities contained within the new paradigm that could not have previously been expressed in the old? *** The following attempt to answer that question will be divided into three parts: first we will look at Rizal’s novel, Noli me tángere, and examine the uneasiness with which the protagonist approached Europe and modernity itself. -

Questioning the Status of Rizal's Women in Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo

Questioning the Status of Rizal's Women in Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo Paulette M. Coulter University of Guam Abstract To an arguable extent, the novels of José Maria Rizal are European novels of the Belle Epoque, despite their setting., and, as such, they reflect the attitude toward women current in Europe in that era. In his novels Rizal’s female characters appear more as stereotypes than archetypes in several broad categories: the good mother (Narcisa), the virgin (Maria Clara, Juli, possibly Paulita Gomez), the harridan (the commandant's wife), the social or religious fanatic (Doña Victorina and Doña Patroncino), for example. In nearly every case in the novels and in his "Letter to the Women of Malolos," however, the individual woman is an exaggeration of an already exaggerated conception of womanhood, with its origins in the work of the Spanish friars. To an arguable extent, the novels of José Maria Rizal are European novels of the Belle Epoque, the golden age at the end of nineteenth century in Europe although their setting is the Philippines, and, as a result, they reflect the attitude toward women current in Europe in that era. Rizal was influenced by both the French novelists Alexandre Dumas, père, and Émile Zola as well as by the European high culture of his time, and his novels rank with theirs in terms of the large numbers of characters, detailed descriptions of the minutiae of everyday life, and complexity of interrelationships of characters in carrying out the plot. Rizal's novels also reflect the ideas of his times on the status and development of women. -

Quarter IV: 20Th and 21St CENTURY MULTIMEDIA FORMS

DOWNLOAD K-12 MATERIALS AT DEPED TAMBAYAN 20th and 21st Century Multimedia Forms richardrrr.blogspot.com Quarter IV: 20th AND 21st CENTURY MULTIMEDIA FORMS CONTENT STANDARDS The learner demonstrates understanding of... 1. Characteristic features of 20th and 21st century opera, musical play, ballet, and other multi-media forms. 2. The relationship among music, technology, and media. PERFORMANCE STANDARDS The learner... 1. Performs selections from musical plays, ballet, and opera in a satisfactory level of performance. 2. Creates a musical work, using media and technology. DEPEDLEARNING COMPETENCIES COPY The learner... 1. Describes how an idea or story in a musical play is presented in a live performance or video. 2. Explains how theatrical elements in a selected part of a musical play are combined with music and media to achieve certain effects. 3. Sings selections from musical plays and opera expressively. 4. Creates/improvises appropriate sounds, music, gestures, movements, and costumes using media and technology for a selected part of a musical play. 5. Presents an excerpt from a 20th or 21st century Philippine musical and highlights its similarities and differences to other Western musical p l a y s . From the Department of Education curriculum for MUSIC Grade 10 (2014) 141 All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means - electronic or mechanical including photocopying without written permission from the DepEd Central Office. MUSIC Quarter IV OPERA IN THE PHILIPPINES he emergence of the Filipino opera started to take shape during the middle part of Tthe 19th century. Foreign performers, including instrumental virtuosi, as well as opera singers and Spanish zarzuela performers came to the country to perform for enthusiastic audiences. -

Philippine History and Government

Remembering our Past 1521 – 1946 By: Jommel P. Tactaquin Head, Research and Documentation Section Veterans Memorial and Historical Division Philippine Veterans Affairs Office The Philippine Historic Past The Philippines, because of its geographical location, became embroiled in what historians refer to as a search for new lands to expand European empires – thinly disguised as the search for exotic spices. In the early 1400’s, Portugese explorers discovered the abundance of many different resources in these “new lands” heretofore unknown to early European geographers and explorers. The Portugese are quickly followed by the Dutch, Spaniards, and the British, looking to establish colonies in the East Indies. The Philippines was discovered in 1521 by Portugese explorer Ferdinand Magellan and colonized by Spain from 1565 to 1898. Following the Spanish – American War, it became a territory of the United States. On July 4, 1946, the United States formally recognized Philippine independence which was declared by Filipino revolutionaries from Spain. The Philippine Historic Past Although not the first to set foot on Philippine soil, the first well document arrival of Europeans in the archipelago was the Spanish expedition led by Portuguese Ferdinand Magellan, which first sighted the mountains of Samara. At Masao, Butuan, (now in Augustan del Norte), he solemnly planted a cross on the summit of a hill overlooking the sea and claimed possession of the islands he had seen for Spain. Magellan befriended Raja Humabon, the chieftain of Sugbu (present day Cebu), and converted him to Catholicism. After getting involved in tribal rivalries, Magellan, with 48 of his men and 1,000 native warriors, invaded Mactan Island. -

Jose Rizal : Re-Discovering the Revolutionary Filipino Hero in the Age of Terrorism

JOSE RIZAL : RE-DISCOVERING THE REVOLUTIONARY FILIPINO HERO IN THE AGE OF TERRORISM BY E. SAN JUAN, Jr. Fellow, WEB Du Bois Institute, Harvard University Yo la tengo, y yo espero que ha de brillar un dia en que venza la Idea a la fuerza brutal, que despues de la lucha y la lenta agonia, otra vzx mas sonora, mas feliz que la mi sabra cantar entonces el cantico triunfal. [I have the hope that the day will dawn/when the Idea will conquer brutal force; that after the struggle and the lingering travail,/another voice, more sonorous, happier than mine shall know then how to sing the triumphant hymn.] -- Jose Rizal, “Mi Retiro” (22 October 1895) On June 19, 2011, we are celebrating 150 years of Rizal’s achievement and its enduring significance in this new millennium. It seems fortuitous that Rizal’s date of birth would fall just six days after the celebration of Philippine Independence Day - the proclamation of independence from Spanish rule by General Emilio Aguinaldo in Kawit, Cavite, in 1898. In 1962 then President Diosdado Macapagal decreed the change of date from July 4 to June 12 to reaffirm the primacy of the Filipinos’ right to national self-determination. After more than three generations, we are a people still in quest of the right, instruments, and opportunity to determine ourselves as an autonomous, sovereign and singular nation-state. Either ironical or prescient, Aguinaldo’s proclamation (read in the context of US Special Forces engaged today in fighting Filipino socialists and other progressive elements) contains the kernel of the contradictions that have plagued the ruling elite’s claim to political legitimacy: he invoked the mythical benevolence of the occupying power. -

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published By

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published by: NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE T.M. Kalaw St., Ermita, Manila Philippines Research and Publications Division: REGINO P. PAULAR Acting Chief CARMINDA R. AREVALO Publication Officer Cover design by: Teodoro S. Atienza First Printing, 1990 Second Printing, 1996 ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 003 — 4 (Hardbound) ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 006 — 9 (Softbound) FILIPINOS in HIS TOR Y Volume II NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 Republic of the Philippines Department of Education, Culture and Sports NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE FIDEL V. RAMOS President Republic of the Philippines RICARDO T. GLORIA Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports SERAFIN D. QUIASON Chairman and Executive Director ONOFRE D. CORPUZ MARCELINO A. FORONDA Member Member SAMUEL K. TAN HELEN R. TUBANGUI Member Member GABRIEL S. CASAL Ex-OfficioMember EMELITA V. ALMOSARA Deputy Executive/Director III REGINO P. PAULAR AVELINA M. CASTA/CIEDA Acting Chief, Research and Chief, Historical Publications Division Education Division REYNALDO A. INOVERO NIMFA R. MARAVILLA Chief, Historic Acting Chief, Monuments and Preservation Division Heraldry Division JULIETA M. DIZON RHODORA C. INONCILLO Administrative Officer V Auditor This is the second of the volumes of Filipinos in History, a com- pilation of biographies of noted Filipinos whose lives, works, deeds and contributions to the historical development of our country have left lasting influences and inspirations to the present and future generations of Filipinos. NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 MGA ULIRANG PILIPINO TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Lianera, Mariano 1 Llorente, Julio 4 Lopez Jaena, Graciano 5 Lukban, Justo 9 Lukban, Vicente 12 Luna, Antonio 15 Luna, Juan 19 Mabini, Apolinario 23 Magbanua, Pascual 25 Magbanua, Teresa 27 Magsaysay, Ramon 29 Makabulos, Francisco S 31 Malabanan, Valerio 35 Malvar, Miguel 36 Mapa, Victorino M. -

2019 Iiee Metro Manila Region Return to Sender

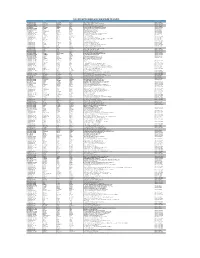

2019 IIEE METRO MANILA REGION RETURN TO SENDER STATUS firstName midName lastname EDITED ADDRESS chapterName RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS ANSELMO FETALVERO ROSARIO Zone 2 Boulevard St. Brgy. May-Iba Teresa Metro East Chapter RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS JULIUS CESAR AGUINALDO ABANCIO 133 MC GUINTO ST. MALASAGA, PINAGBUHATAN PASIG . Metro Central Chapter RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS ALVIN JOHN CLEMENTE ABANO NARRA STA. ELENA IRIGA Metro Central Chapter RTS INSUFFICIENT ADDRESS Gerald Albelda Abantao NO.19 . BRGY. KRUS NA LIGAS. DILIMAN QUEZON CITY Metro East Chapter RTS NO RECEIVER JEAN MIGHTY DECIERDO ABAO HOLCIM PHILIPPINES INC. MATICTIC NORZAGARAY BULACAN Metro Central Chapter RTS INSUFFICIENT ADDRESS MICHAEL HUGO ABARCA avida towers centera edsa cor. reliance st. mandaluyong city Metro West Chapter RTS UNLOCATED ADDRESS Jeffrey Cabagoa ABAWAG 59 Gumamela Sta. Cruz Antipolo Rizal Metro East Chapter RTS NO RECEIVER Angelbert Marvin Dolinso ABELLA Road 12 Nagtinig San Juan Taytay Rizal Metro East Chapter RTS INSUFFICIENT ADDRESS AHERN SATENTES ABELLA NAGA-NAGA BRGY. 71 TACLOBAN Metro South Chapter RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS JOSUE DANTE ABELLA JR. 12 CHIVES DRIVE ROBINSONS HOMES EAST SAN JOSE ANTIPOLO CITY Metro East Chapter RTS INSUFFICIENT ADDRESS ANDREW JULARBAL ABENOJA 601 ACACIA ESTATE TAGUIG CITY METRO MANILA Metro West Chapter RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS LEONARDO MARQUEZ ABESAMIS, JR. POBLACION PENARANDA Metro Central Chapter RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS ELONA VALDEZ ABETCHUELA 558 M. de Jesus St. San Roque Pasay City Metro South Chapter RTS UNLOCATED ADDRESS Franklin Mapa Abila LOT 3B ATIS ST ADMIRAL VILLAGE TALON TRES LAS PINAS CITY METRO MANILA Metro South Chapter RTS MOVED OUT Marie Sharon Segovia Abilay blk 10 lot 37 Alicante St. -

Indiana University Bloomington

ARCHIVE lUCD .A69.L2 )).4-1 INDIANA UNIVERSITY pt . 2 SCHOOL OF MUSIC Five Hundred Eleventh Program of the 2004-05 Season Faculty/Student Recital Httkan Hagegttrd, Director The Andree Expedition (1987) .... ' .' ....... .. Dominick Argento Part One: In the Air (born 1927) Prologue The Balloon Rises Pride and Ambition Dinner Aloft The Unforeseen Problem The Flight Aborted Part Two: On the Ice Mishap with a Sledge The King's Jubilee Illness and Drugs Hallucinations Anna's Birthday Epilogue Final Words Andree: Samuel Spade Strindberg: David Swain Fraenkel: Joseph Legaspi Piano: Gregory Martin Intermission Auer Concert Hall Sunday Evening February Thirteenth Eight O'clock music.indiana.edu A Few Words about Chekhov I Duo 2 Solo (Olga) 3 Solo (Anton) 4 Duo 5 Solo (Olga) 6 Solo (Anton) 7 Duo Chekhov: Benjamin Czamota Olga: Sarah McCormack Piano: Meeyoun Park Intermission From the Diary of Virginia Woolf(1975) The Diary Anxiety Fancy Hardy's Funeral Rome War Parents Last Entry Virginia: Lisa LaFleur Student: Sarah Daughtrey Piano (Vanessa): Daniela Candillari l['JH[]E ". , ;: ~ ',:2 ___ ~-~.- -..;~~ ...~ ~~.~=~~- .~~ - ANDREE EXPEDITION FOUND! the settlements and evacu and businesses are in limbo," Wouldn't it be reasonable to Mystery solved after 30 years ate the settlers without being said Phil Borst, the council's provide coverage of some of the STOCKHOLM, Feb 10 shot at. And quiet will make it Republican minority leader more uplifting aspects of hu Thirty-three years after their much easier for Mr. Abbas to who represents a district near man behavior? Your choice to departure from Sweden, on a carry out his urgent domestic the planned route.