The Construction and Performance of Race in American Professional Wrestling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unintended Consequences of the American Presidential Selection System

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLP\15-1\HLP104.txt unknown Seq: 1 14-JUL-21 12:54 The Best Laid Plans: Unintended Consequences of the American Presidential Selection System Samuel S.-H. Wang and Jacob S. Canter* The mechanism for selecting the President of the United States, the Electoral College, causes outcomes that weaken American democracy and that the delegates at the Constitu- tional Convention never intended. The core selection process described in Article II, Section 1 was hastily drawn in the final days of the Convention based on compromises made originally to benefit slave-owning states and states with smaller populations. The system was also drafted to have electors deliberate and then choose the President in an age when travel and news took weeks or longer to cross the new country. In the four decades after ratification, the Electoral College was modified further to reach its current form, which includes most states using a winner-take-all method to allocate electors. The original needs this system was designed to address have now disappeared. But the persistence of these Electoral College mechanisms still causes severe unanticipated problems, including (1) con- tradictions between the electoral vote winner and national popular vote winner, (2) a “battleground state” phenomenon where all but a handful of states are safe for one political party or the other, (3) representational and policy benefits that citizens in only some states receive, (4) a decrease in the political power of non-battleground demographic groups, and (5) vulnerability of elections to interference. These outcomes will not go away without intervention. -

Here We Are at 500! the BRL’S 500 to Be Exact and What a Trip It Has Been

el Fans, here we are at 500! The BRL’s 500 to be exact and what a trip it has been. Imagibash 15 was a huge success and the action got so intense that your old pal the Teamster had to get involved. The exclusive coverage of that ppv is in this very issue so I won’t spoil it and give away the ending like how the ship sinks in Titanic. The Johnny B. Cup is down to just four and here are the representatives from each of the IWAR’s promotions; • BRL Final: Sir Gunther Kinderwacht (last year’s winner) • CWL Final: Jane the Vixen Red (BRL, winner of 2017 Unknown Wrestler League) • IWL Final: Nasty Norman Krasner • NWL Final: Ricky Kyle In one semi-final, we will see bitter rivals Kinderwacht and Red face off while in the other the red-hot Ricky Kyle will face the, well, Nasty Normal Krasner. One of these four will win The self-professed “Greatest Tag team wrestler the 4th Johnny B Cup and the results will determine the breakdown of the prizes. ? in the world” debuted in the NWL in 2012 and taunt-filled promos earned him many enemies. The 26th Marano Memorial is also down to the final 5… FIVE? Well since the Suburban Hell His “Teamster Challenge” offered a prize to any Savages: Agent 26 & Punk Rock Mike and Badd Co: Rick Challenger & Rick Riley went to a NWL rookie who could capture a Tag Team title draw, we will have a rematch. The winner will advance to face Sledge and Hammer who won with him, but turned ugly when he kept blaming the CWL bracket. -

POLL RESULTS: Congressional Bipartisanship Nationwide and in Battleground States

POLL RESULTS: Congressional Bipartisanship Nationwide and in Battleground States 1 Voters think Congress is dysfunctional and reject the suggestion that it is effective. Please indicate whether you think this word or phrase describes the United States Congress, or not. Nationwide Battleground Nationwide Independents Battleground Independents Dysfunctional 60 60 61 64 Broken 56 58 58 60 Ineffective 54 54 55 56 Gridlocked 50 48 52 50 Partisan 42 37 40 33 0 Bipartisan 7 8 7 8 Has America's best 3 2 3 interests at heart 3 Functioning 2 2 2 3 Effective 2 2 2 3 2 Political frustrations center around politicians’ inability to collaborate in a productive way. Which of these problems frustrates you the most? Nationwide Battleground Nationwide Independents Battleground Independents Politicians can’t work together to get things done anymore. 41 37 41 39 Career politicians have been in office too long and don’t 29 30 30 30 understand the needs of regular people. Politicians are politicizing issues that really shouldn’t be 14 13 12 14 politicized. Out political system is broken and doesn’t work for me. 12 15 12 12 3 Candidates who brand themselves as bipartisan will have a better chance of winning in upcoming elections. For which candidate for Congress would you be more likely to vote? A candidate who is willing to compromise to A candidate who will stay true to his/her get things done principles and not make any concessions NationwideNationwide 72 28 Nationwide Nationwide Independents Independents 74 26 BattlegroundBattleground 70 30 Battleground Battleground IndependentsIndependents 73 27 A candidate who will vote for bipartisan A candidate who will resist bipartisan legislation legislation and stick with his/her party NationwideNationwide 83 17 Nationwide IndependentsNationwide Independents 86 14 BattlegroundBattleground 82 18 Battleground BattlegroundIndependents Independents 88 12 4 Across the country, voters agree that they want members of Congress to work together. -

The Rise of Controversial Content in Film

The Climb of Controversial Film Content by Ashley Haygood Submitted to the Department of Communication Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Communication at Liberty University May 2007 Film Content ii Abstract This study looks at the change in controversial content in films during the 20th century. Original films made prior to 1968 and their remakes produced after were compared in the content areas of profanity, nudity, sexual content, alcohol and drug use, and violence. The advent of television, post-war effects and a proposed “Hollywood elite” are discussed as possible causes for the increase in controversial content. Commentary from industry professionals on the change in content is presented, along with an overview of American culture and the history of the film industry. Key words: film content, controversial content, film history, Hollywood, film industry, film remakes i. Film Content iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family for their unwavering support during the last three years. Without their help and encouragement, I would not have made it through this program. I would also like to thank the professors of the Communications Department from whom I have learned skills and information that I will take with me into a life-long career in communications. Lastly, I would like to thank my wonderful Thesis committee, especially Dr. Kelly who has shown me great patience during this process. I have only grown as a scholar from this experience. ii. Film Content iv Table of Contents ii. Abstract iii. Acknowledgements I. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………1 II. Review of the Literature……………………………………………………….8 a. -

The Popular Culture Studies Journal

THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 2018 Editor NORMA JONES Liquid Flicks Media, Inc./IXMachine Managing Editor JULIA LARGENT McPherson College Assistant Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY Mid-America Christian University Copy Editor Kevin Calcamp Queens University of Charlotte Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON Indiana State University Assistant Reviews Editor JESSICA BENHAM University of Pittsburgh Please visit the PCSJ at: http://mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture- studies-journal/ The Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. Copyright © 2018 Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 Cover credit: Cover Artwork: “Wrestling” by Brent Jones © 2018 Courtesy of https://openclipart.org EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD ANTHONY ADAH FALON DEIMLER Minnesota State University, Moorhead University of Wisconsin-Madison JESSICA AUSTIN HANNAH DODD Anglia Ruskin University The Ohio State University AARON BARLOW ASHLEY M. DONNELLY New York City College of Technology (CUNY) Ball State University Faculty Editor, Academe, the magazine of the AAUP JOSEF BENSON LEIGH H. EDWARDS University of Wisconsin Parkside Florida State University PAUL BOOTH VICTOR EVANS DePaul University Seattle University GARY BURNS JUSTIN GARCIA Northern Illinois University Millersville University KELLI S. BURNS ALEXANDRA GARNER University of South Florida Bowling Green State University ANNE M. CANAVAN MATTHEW HALE Salt Lake Community College Indiana University, Bloomington ERIN MAE CLARK NICOLE HAMMOND Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota University of California, Santa Cruz BRIAN COGAN ART HERBIG Molloy College Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne JARED JOHNSON ANDREW F. HERRMANN Thiel College East Tennessee State University JESSE KAVADLO MATTHEW NICOSIA Maryville University of St. -

World Latin American Agenda 2016

World Latin American Agenda 2016 In its category, the Latin American book most widely distributed inside and outside the Americas each year. A sign of continental and global communion among individuals and communities excited by and committed to the Great Causes of the Patria Grande. An Agenda that expresses the hope of the world’s poor from a Latin American perspective. A manual for creating a different kind of globalization. A collection of the historical memories of militancy. An anthology of solidarity and creativity. A pedagogical tool for popular education, communication and social action. From the Great Homeland to the Greater Homeland. Our cover image by Maximino CEREZO BARREDO. See all our history, 25 years long, through our covers, at: latinoamericana.org/digital /desde1992.jpg and through the PDF files, at: latinoamericana.org/digital This year we remind you... We put the accent on vision, on attitude, on awareness, on education... Obviously, we aim at practice. However our “charisma” is to provoke the transformations of awareness necessary so that radically new practices might arise from another systemic vision and not just reforms or patches. We want to ally ourselves with all those who search for that transformation of conscience. We are at its service. This Agenda wants to be, as always and even more than at other times, a box of materials and tools for popular education. latinoamericana.org/2016/info is the web site we have set up on the network in order to offer and circulate more material, ideas and pedagogical resources than can economically be accommo- dated in this paper version. -

Post-Gazette 8-10-12.Pmd

VOL. 116 - NO. 32 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, AUGUST 10, 2012 $.30 A COPY GREENWAY SPARKS CONTROVERSY OVER “TERRORIST” IMAGE by Sal Giarratani A debate has begun over a ored figures are iconic and by Julius Mourlon at the new mural in Dewey Square recurrent feature” in the Crono Festival in Lisbon not far from the Occupy work of these artistic sib- back in 2010. It is very simi- Boston site that depicts a lings and that “the figures lar to the Greenway mural large character peering out are frequently shown wear- except for the covering on from behind a red shirt ing whimsical hats, colorful the head and without a wrapped around the head. hoods or scarves — another crane positioned close to the Boston’s Fox 25 posted a hallmark feature of the art- character’s hand, leading photo of the 70 by 70 foot ists’ work.” me and many others to see mural on its Facebook page I viewed the photo and the it as an automatic weapon and within 24 hours had lots first thing I saw was a hooded that terrorists often use. of feedback. Most viewers of terrorist-looking character. Why wasn’t the crane re- the mural photo are under, If the purpose of this mural moved when the mural was what the Metro newspaper is to “bring color and energy completed? Many assume said was “the wrong impres- to the streets of Boston as that the crane was left there sion that the cartoon char- well as inspire curiosity and to add to the whole imagina- acter is wearing a Muslim imagination,” as the ICA tion thing. -

Grappling with Race: a Textual Analysis of Race Within the Wwe

GRAPPLING WITH RACE: A TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF RACE WITHIN THE WWE BY MARQUIS J. JONES A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Communication April 2019 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Ronald L. Von Burg, PhD, Advisor Jarrod Atchison, PhD, Chair Eric K. Watts, PhD ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Ron Von Burg of the Communication Graduate School at Wake Forest University. Dr. Von Burg’s office was always open whenever I needed guidance in the completion of this thesis. He consistently allowed this paper to be my own work, but steered me in the right direction whenever he thought I needed. I would also like to thank Dr. Jarrod Atchison and Dr. Eric Watts for serving as committed members of my Graduate Thesis Committee. I truly appreciate the time and energy that was devoted into helping me complete my thesis. Finally, I must express my very profound gratitude to my parents, Marcus and Erika Jones, for providing me with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout my years of sturdy and through the process of research and writing this thesis. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. Thank you. I love you both very much. Thank you again, Marquis Jones iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………..iv Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION………………………………………………Pg. 1 Chapter 2: HISTORY OF WWE……………………………………………Pg. 15 Chapter 3: RACIALIZATION IN WWE…………………………………..Pg. 25 Chapter 4: CONCLUSION………………………………………………......Pg. -

November 19, 1987 in Troy, OH Hobart Arena Drawing ??? 1. NWA

November 19, 1987 in Troy, OH Hobart Arena drawing ??? 1. NWA U.S. Tag Champs The Midnight Express (Eaton & Lane) vs. The Rock-n-Roll Express. November 5, 1988 in Dayton, OH UD Arena drawing ??? ($20,000) 1. The Sheepherders vs. ???. 2. Al Perez & Larry Zbyszko vs. Ron Simmons & The Italian Stallion. 3. Rick Steiner vs. Russian Assassin #2. 4. Bam Bam Bigelow & Jimmy Garvin vs. Mike Rotunda & Kevin Sullivan. 5. Ivan Koloff vs. Russian Assassin #1. 6. NWA U.S. Champ Barry Windham vs. Nikita Koloff. 7. The Midnight Express (Eaton & Lane) Vs. The Fantastics (Fulton & Rogers). 8. Lex Luger beat NWA World Champ Ric Flair via DQ. February 22, 1989 in Centerville, OH Centerville High school drawing 600 1. Match results unavailable. April 24, 1989 in Dayton, OH UD Arena drawing ??? 1. Shane Douglas beat Doug Gilbert. 2. The Great Muta beat George South. 3. The Samoan Swat Team beat Bob Emory & Mike Justice. 4. Ranger Ross beat The Iron Sheik. 5. NWA TV Champ Sting beat Mike Rotunda. 6. Ricky Steamboat & Lex Luger beat Ric Flair & Michael Hayes. Great American Bash 1989 July 21, 1989 in Dayton, OH UD Arena drawing ??? 1. Brian Pillman beat Bill Irwin. 2. Sid Vicious & Dan Spivey beat Johnny & Davey Rich. 3. Norman beat Scott Casey. 4. Scott Steiner beat Mike Rotunda via DQ. 5. Steve Williams beat ???. 6. Sid Vicious and Dan Spivey won a “two ring battle royal.” 7. The Midnight Express (Eaton & Lane) beat Rip Morgan & Jack Victory. 8. The Road Warriors beat The Samoan Swat Team. 9. NWA TV Champ Sting beat Norman. -

Fitment Chart (Pdf)

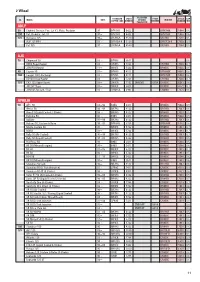

2 Wheel PLATINUM CC MODEL DATE STANDARD STOCK OR GOLD STOCK IRIDIUM STOCK GAP COPPER CORE NUMBER PALLADIUM NUMBER NUMBER MM ADLY 50 Citybird, Crosser, Fox, Jet X1, Pista, Predator 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 100 Cat, Predator, Jet, X1 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 125 Activator 125 99 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJP 125 PR4 03 DPR7EA-9 5129 DPR7EIX-9 7803 0.9 Cat 125 97 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJS 50 Chipmunk 50 03 BP4HS 3611 0.6 DD50 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 JSM 50 Motard 11 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 80 Coyote 80 03 BP6HS 4511 BPR6HIX 4085 0.6 100 Cougar 100 (Jincheng) 03 BP7HS 5111 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 DD100 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 125 CR3-125 Super Sports 08 DR8EA 7162 DR8EVX 6354 DR8EIX 6681 0.6 JS125Y Tiger 03 DR8ES 5423 DR9EIX 4772 0.7 JSM125 Motard / Trail 10 CR6HSA 2983 CR6HIX 7274 0.6 APRILIA 50 AF1 50 8892 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Amico 50 9294 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Area 51 (Liquid Cooled 2-Stroke) 98 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Extrema 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Gulliver 9799 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Habana 50, Custom & Retro 9905 BPR8HS 3725 BPR8HIX 6742 0.6 Mojito Custom 50 05 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 MX50 03 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 Rally 50 (Air Cooled) 9599 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.7 Rally 50 (Liquid Cooled) 9703 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Red Rose 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 RS 50 (Minarelli engine) 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 RS 50 0105 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 RS 50 06 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.5 RS4 50 1113 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 ‡ Early Ducati Testastretta bikes (749, 998, 999 models) can have very little clearance between the plug hex and the RX 50 (Minarelli engine) 97 B9ES 2611 BR9EIX 3981 0.6 cylinder head that may require a thin walled socket, no larger than 20.5mm OD to allow the plug to be fitted. -

PWTORCH NEWSLETTER • PAGE 2 Www

ISSUE #1255 - MAY 26, 2012 TOP FIVE STORIES OF THE WEEK PPV ROUNDTABLE (1) Raw expanding to three hours on July 23 (2) Impact going live every week this summer (3) Flair parting ways with TNA, WWE bound WWE OVER THE LIMIT (4) Raw going “interactive” with weekly voting Staff Scores & Reviews (5) Laurinaitis pins Cena after Show turns heel Pat McNeill, columnist (6.5): The main problem with WWE Over The Limit? The main event went over the limit of what we’ll accept from WWE. You can argue that there was no reason to book John Cena against John Laurinaitis on a pay-per-view, and you’d be right. RawHEA eDLxINpE AaNnALYdSsIS to thrhoeurse, a nhd uosuaullyr tsher e’Js eunoulgyh re2de3eming But on top of that, there was no reason to book content to make it worth the investment. But Cena versus Laurinaitis to go as long as any other three hours? Three hours of lousy content is By Wade Keller, editor major pay-per-view match. And there was no enough that next time viewers might just tune in reason for Cena to drag the match out. It didn’t fit If you follow an industry long enough, you’re for a just an hour instead of the usual two and the storyline. And it made John Cena look like a bound to see some bad decisions being made. certainly not commit to all three. Or they might chump. or like The Stinger, when Big Show turned Some are worse than others, but it’s rare when pick their segments, watching the predictably heel for the umpteenth time and cost him the you think you might be seeing the Worst newsmaking segments at the start of each hour match. -

Pay-Per-View

Pay-Per-View Don’t bother with the babysitter. Stop worrying about traffic. Because with Pay Per View, you get the best seats in the house without ever leaving home. From UFC fights to exclusive concerts, watch the best in live sports and entertainment right on your own TV. Ordering made easy No need to call or go online. Just order with your remote. From the Guide menu, go to the Pay Per View event channel (PPV) to see what’s playing this month. Once you’ve made your selection, all you need to do is select “Watch” and then confirm your order. It’s that easy. What’s new this month? Combate Americas: Tito vs Alberto December 7th, 2019, 9:00 p.m. ET / 6:00 p.m. PT Legendary combat sports icons Tito Ortiz and Alberto El Patron (formerly “Alberto Del Rio” of the WWE) will battle in a winner take all title belt challenge inside the Combate Americas “La Juala” cage. If Ortiz emerges victorious in the bout, he will take possession of El Patron’s WWE title belt. SD standard definition $29.99 HD high definition $29.99 Channels 325 and 612 (BlueSky TV SD) Channels 301 and 602 (BlueSky TV HD) Replays: Available until December 13th, 2019 Ring of Honor: Final Battle 2019 December 13th, 2019, 9:00 p.m. ET / 6:00 p.m. PT At Ring Of Honor: Final Battle 2019 in Baltimore, ROH World Champion RUSH will put his title and undefeated record on the line against PCO. SD standard definition $34.99 HD high definition $44.99 Channels 324 and 611 (BlueSky TV SD) Channels 300 and 601 (BlueSky TV HD) Replays: Available until March 13th, 2019 UFC 245: Usman vs Covington December 13th, 2019, 10:00 p.m.