Kachin State Development Prospects and Priorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mandy Sadan Syphilis and the Kachin Regeneration Campaign, 1937–38 This Paper Discusses the Introduction of a Policy Known As

Please note: This paper is an early draft of a paper that was later published as Sadan, Mandy (2010) 'Syphilis and the Kachin Regeneration Campaign, 1937– 38.' Journal of Burma Studies, 14 . pp. 115-149. The published version should be cited. Mandy Sadan Syphilis and the Kachin Regeneration Campaign, 1937–38 This paper discusses the introduction of a policy known as the Kachin Regeneration Campaign in the Kachin Hills from 1937 to 1938. Initiated by a belief that the Kachin people were on the verge of dying out because of an epidemic of syphilis, the campaign reveals much about the realities of Kachin dissociation from the late colonial regime, contrasting sharply with the conventional historical narrative of Kachin compliance with imperial control. A significant part of the Regeneration Campaign’s agenda was a less publicly acknowledged awareness that former Kachin soldiers were becoming a potentially volatile interest group and that there was increasing discontent across the Kachin Hills with regard to the administration, the military and the missions. The paper uses the concept of a sick role to describe the approach of the Regeneration Campaign to Kachin society and discusses how the rhetoric of the campaign became embedded in the sermons of the local Christian missions, justifying changes to women’s roles and more recently impacting upon early responses to the spread of HIV/AIDS in the region. It is the general belief of all who are acquainted with the Kachin Hills, that the Kachins are a dying race doomed shortly to disappear unless specific measures are taken to save them. -

KACHIN STATE, BHAMO DISTRICT Bhamo Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census KACHIN STATE, BHAMO DISTRICT Bhamo Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Kachin State, Bhamo District Bhamo Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1: Map of Kachin State, showing the townships Bhamo Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 135,877 2 Population males 66,718 (49.1%) Population females 69,159 (50.9%) Percentage of urban population 43.2% Area (Km2) 1,965.8 3 Population density (per Km2) 69.1 persons Median age 25.2 years Number of wards 13 Number of village tracts 45 Number of private households 24,161 Percentage of female headed households 29.7% Mean household size 4.9 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 30.5% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 64.8% Elderly population (65+ years) 4.7% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 54.2 Child dependency ratio 46.9 Old dependency ratio 7.3 Ageing index 15.5 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 97 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 94.7% Male 96.8% Female 93.0% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 7,448 5.5 Walking 2,977 2.2 Seeing 4,114 3.0 Hearing 2,262 1.7 Remembering 2,380 1.8 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny 81,655 74.7 Associate Scrutiny -

Title <Book Reviews>Mandy Sadan. 『Being and Becoming Kachin

<Book Reviews>Mandy Sadan. 『Being and Becoming Title Kachin: Histories Beyond the State in the Borderworlds of Burma』 Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, 470p. Author(s) Imamura, Masao Citation Southeast Asian Studies (2015), 4(1): 199-206 Issue Date 2015-04 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/197733 Right ©Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Book Reviews 199 Being and Becoming Kachin: Histories Beyond the State in the Borderworlds of Burma MANDY SADAN Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, 470p. Over the past 15 years, Mandy Sadan has single-handedly launched new historical scholarship on the Kachin people. The Kachin, a group of highlanders who mostly reside in the northern region of Myanmar, had long been widely known among academics, thanks to Edmund Leach’s 1954 clas- sic Political Systems of Highland Burma: A Study of Kachin Social Structure. The lack of access to Myanmar, however, has meant that until very recently scholarly discussions were often more about Leach and his theory than about the Kachin people themselves. Sadan, an English historian, has introduced an entirely new set of historical studies from a resolutely empirical perspective. The much-anticipated monograph, Being and Becoming Kachin: Histories Beyond the State in the Border- worlds of Burma, brings together the fruits of her scholarship, including a surprisingly large amount of findings that have not been published before. This publication is certainly a cause for celebration, especially because it is rare that such a thick monograph exclusively focused on one ethnic minor- ity group is published at all nowadays.1) With this monograph, Sadan has again raised the standard of Kachin scholarship to a new level. -

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar Asia Report N°312 | 28 August 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Legacy of Division ......................................................................................................... 4 A. Who Lives in Myanmar? ............................................................................................ 4 B. Those Who Belong and Those Who Don’t ................................................................. 5 C. Contemporary Ramifications..................................................................................... 7 III. Liberalisation and Ethno-nationalism ............................................................................. 9 IV. The Militarisation of Ethnicity ......................................................................................... 13 A. The Rise and Fall of the Kaungkha Militia ................................................................ 14 B. The Shanni: A New Ethnic Armed Group ................................................................. 18 C. An Uncertain Fate for Upland People in Rakhine -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

Grave Diggers a Report on Mining in Burma

GRAVE DIGGERS A REPORT ON MINING IN BURMA BY ROGER MOODY CONTENTS Abbreviations........................................................................................... 2 Map of Southeast Asia............................................................................. 3 Acknowledgments ................................................................................... 4 Author’s foreword ................................................................................... 5 Chapter One: Burma’s Mining at the Crossroads ................................... 7 Chapter Two: Summary Evaluation of Mining Companies in Burma .... 23 Chapter Three: Index of Mining Corporations ....................................... 29 Chapter Four: The Man with the Golden Arm ....................................... 43 Appendix I: The Problems with Copper.................................................. 53 Appendix II: Stripping Rubyland ............................................................. 59 Appendix III: HIV/AIDS, Heroin and Mining in Burma ........................... 61 Appendix IV: Interview with a former mining engineer ........................ 63 Appendix V: Observations from discussions with Burmese miners ....... 67 Endnotes .................................................................................................. 68 Cover: Workers at Hpakant Gem Mine, Kachin State (Photo: Burma Centrum Nederland) A Report on Mining in Burma — 1 Abbreviations ASE – Alberta Stock Exchange DGSE - Department of Geological Survey and Mineral Exploration (Burma) -

THE STATE of LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS in KACHIN Photo Credits

Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN KACHIN Photo credits Mike Adair Emilie Röell Myanmar Survey Research A photo record of the UNDP Governance Mapping Trip for Kachin State. Travel to Tanai, Putao, Momauk and Myitkyina townships from Jan 6 to Jan 23, 2015 is available here: http://tinyurl.com/Kachin-Trip-2015 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP. Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN KACHIN UNDP MYANMAR Table of Contents Acknowledgements II Acronyms III Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 5 2. Kachin State 7 2.1 Kachin geography 9 2.2 Population distribution 10 2.3 Socio-economic dimensions 11 2.4 Some historical perspectives 13 2.5 Current security situation 18 2.6 State institutions 18 3. Methodology 24 3.1 Objectives of mapping 25 3.2 Mapping tools 25 3.3 Selected townships in Kachin 26 4. Governance at the front line – Findings on participation, responsiveness and accountability for service provision 27 4.1 Introduction to the townships 28 4.1.1 Overarching development priorities 33 4.1.2 Safety and security perceptions 34 4.1.3 Citizens’ views on overall improvements 36 4.1.4 Service Provider’s and people’s views on improvements and challenges in selected basic services 37 4.1.5 Issues pertaining to access services 54 4.2 Development planning and participation 57 4.2.1 Development committees 58 4.2.2 Planning and use of development funds 61 4.2.3 Challenges to township planning and participatory development 65 4.3 Information, transparency and accountability 67 4.3.1 Information at township level 67 4.3.2 TDSCs and TMACs as accountability mechanisms 69 4.3.3 WA/VTAs and W/VTSDCs 70 4.3.4 Grievances and disputes 75 4.3.5 Citizens’ awareness and freedom to express 78 4.3.6 Role of civil society organisations 81 5. -

Kahrl Navigating the Border Final

CHINA AND FOREST TRADE IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGION: IMPLICATIONS FOR FORESTS AND LIVELIHOODS NAVIGATING THE BORDER: AN ANALYSIS OF THE CHINA- MYANMAR TIMBER TRADE Fredrich Kahrl Horst Weyerhaeuser Su Yufang FO RE ST FO RE ST TR E ND S TR E ND S COLLABORATING INSTITUTIONS Forest Trends (http://www.forest-trends.org): Forest Trends is a non-profit organization that advances sustainable forestry and forestry’s contribution to community livelihoods worldwide. It aims to expand the focus of forestry beyond timber and promotes markets for ecosystem services provided by forests such as watershed protection, biodiversity and carbon storage. Forest Trends analyzes strategic market and policy issues, catalyzes connections between forward-looking producers, communities, and investors and develops new financial tools to help markets work for conservation and people. It was created in 1999 by an international group of leaders from forest industry, environmental NGOs and investment institutions. Center for International Forestry Research (http://www.cifor.cgiar.org): The Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), based in Bogor, Indonesia, was established in 1993 as a part of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) in response to global concerns about the social, environmental, and economic consequences of forest loss and degradation. CIFOR research produces knowledge and methods needed to improve the wellbeing of forest-dependent people and to help tropical countries manage their forests wisely for sustained benefits. This research is conducted in more than two dozen countries, in partnership with numerous partners. Since it was founded, CIFOR has also played a central role in influencing global and national forestry policies. -

KACHIN STATE Myanmar

Myanmar Information Management Unit KACHIN STATE Myanmar 95°30'E 96°0'E 96°30'E 97°0'E 97°30'E 98°0'E 98°30'E 99°0'E 28°30'N Ü 28°30'N 28°0'N 28°0'N Nawngmun INDIA Puta-O Pannandin !( Nawngmun 27°30'N 27°30'N Putao oAirport Machanbaw Puta-O Pansaung !( Khaunglanhpu Machanbaw Khaunglanhpu Nanyun 27°0'N 27°0'N Don Hee !( !( Shin Bway Yang Sumprabum Sumprabum Tanai 26°30'N 26°30'N KACHIN Tsawlaw Tanai Lahe Tsawlaw Injangyang Htan Par Hkamti Kway 26°0'N o Khamti 26°0'N Airport Chipwi Injangyang Chipwi Myitkyina Hpakan Pang War Hpakan !( Kamaing !( 25°30'N 25°30'N Myitkyina Kan Mogaung Airport o Paik Ti Nampong Sadung !( oAir Base .!Myitkyina !( Mogaung Waingmaw Waingmaw SAGAING LAKE INDAWNGYI !( 25°0'N Hopin CHINA 25°0'N Mohnyin !( Mohnyin Sinbo Momauk Dawthponeyan !( Myo Hla 24°30'N !( 24°30'N Banmauk Bhamo Shwegu Bamaw SAGAING oAirport Momauk Shwegu Bhamo Indaw Katha !( Lwegel Mansi Pinlebu !( Maw !( !( Monekoe Hteik Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Manhlyoe 24°0'N (Manhero) Muse 24°0'N Mansi !( Wuntho Konkyan Namhkan Kilometers Kawlin Tigyaing 0 15 30 60 90 SHAN Laukkaing 95°30'E 96°0'E 96°30'E 97°0'E 97°30'E 98°0'E 98°30'E 99°0'E Tarmoenye !( Legend Elevation (Meter) Map ID: MIMU940v01 Takaung < 50 1,250 - 1,500 3,000 - 3,250 Data Sources : Myanmar Information Management Unit (MIMU) is a !( o Major Road Township Boundary River/Water Body Creation Date: 4 December 2012.A1 Airports Mabein 50 - 100 1,500 - 1,750 3,250 - 3,500 Base Map - MIMU ChinshwehawcommonNamtit resource of the Humanitarian Country Team Other Road District Boundary Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 Non-Perennial 100 - 250 1,750 - 2,000 3,500 - 3,750 Boundaries - WFP/MIMU (HCT) providing information management services, ^(!_ Capital including GIS mapping and analysis, to the humanitarian Railway State/Region Boundary Perennial 250 - 500 2,000 - 2,250 3,750 - 4,000 River and Stream - DCW Elevation : SRTM 90m and development actors both inside and outside of .! State Capital River and Stream International Boundary 500 - 750 2,250 - 2,500 4,000 - 7,007 Place names - Ministry of Home Affair Myanmar. -

Conspiracy, God's Plan and National Emergency

CHAPTER EIGHT Conspiracy, God’s Plan and National Emergency Kachin Popular Analyses of the Ceasefire Era and its Resource Grabs Laur Kiik Introduction isiting Yangon in 2014, I noticed some well-meaning locals refer to the dragging Kachin military-political impasse by stat- ing: ‘The Kachins are being too stubborn, too emotional now’. OtherV observers find such talk belittling. They respond by emphasising how ‘The Kachins merely demand that Myanmar begin genuine political dialogue on federalism’ and ‘are thus correct in refusing simply to sign a new ceasefire’. This oscillation between explaining the Kachin impasse either through collective emotional trauma or through formal political discourse misses what Mandy Sadan identified in her monograph on Kachin histories as ‘social worlds beyond’.1 As this chapter tries to show, these are diverse, contradictory, and ambitious social worlds that people live within. They cannot be encapsulated by inaccurate and homogenis- ing expressions like ‘the Kachins’, ‘are emotional’, or ‘want federalism’. It is the argument of this chapter that the way people in these worlds understand their ceasefire experiences to express ethno-national emergency, divine predestination, and ethnocidal conspiracy influences directly their contemporary responses to ceasefire politics. 1. Mandy Sadan, Being and Becoming Kachin: Histories Beyond the State in the Border- worlds of Burma (Oxford: The British Academy and Oxford University Press, 2013), 455–60. 205 War and Peace in the Borderlands of Myanmar Figure 8.1: Many Kachin patriots are working for a future Kachin national modernity – a homeland yet-to-be (photo Hpauyam Awng Di). Many chapters in this volume refer to a hardening of Kachin na- tionalist rhetoric in recent years, in particular the chapters by Mahkaw Hkun Sa, Nhkum Bu Lu, Jenny Hedström, and Hkanhpa Tu Sadan. -

Myanmar Opium Survey 2018 Cultivation, Production and Implications

Central Committee for Drug Abuse Control Myanmar Opium Survey 2018 Cultivation, Production and Implications Research In Southeast Asia, UNODC supports Member States to develop and implement evidence‐ based rule of law, drug control and related criminal justice responses through the Regional Programme 2014‐2018 and aligned country programmes including the Myanmar Country Programme 2014‐2018. This study is connected to the Mekong MOU on Drug Control which UNODC actively supports through the Regional Programme, including the commitment to develop data and evidence as the basis for countries of the Mekong region to respond to challenges of drug production, trafficking and use. UNODC’s Research and Trend Analysis Branch promotes and supports the development and implementation of surveys globally, including through its Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme (ICMP). The implementation of Myanmar opium survey was made possible thanks to the financial support of the Governments of Japan, the United States of America and China. UNODC Regional Office for Southeast Asia and the Pacific Telephone: +6622882100 Fax: +6622812129 Email: unodc‐[email protected] Website: www.unodc.org/southeastasiaandpacific Twitter: @UNODC_SEAP The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNODC concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Front cover photos: Jeremy -

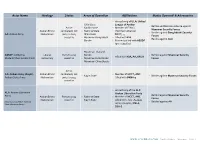

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security