National Inventory and Prioritization of Crop Wild Relatives: Case Study for Benin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Revised February 24, 2017 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. -

The Evolution of Sexual Reproduction in Cuscuta (Convolvulaceae)

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2011 The Evolution of Sexual Reproduction in Cuscuta (Convolvulaceae) Michael Wright Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Plant Breeding and Genetics Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Michael, "The Evolution of Sexual Reproduction in Cuscuta (Convolvulaceae)" (2011). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1039. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1039 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-75396-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-75396-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciaies ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Appendix Color Plates of Solanales Species

Appendix Color Plates of Solanales Species The first half of the color plates (Plates 1–8) shows a selection of phytochemically prominent solanaceous species, the second half (Plates 9–16) a selection of convol- vulaceous counterparts. The scientific name of the species in bold (for authorities see text and tables) may be followed (in brackets) by a frequently used though invalid synonym and/or a common name if existent. The next information refers to the habitus, origin/natural distribution, and – if applicable – cultivation. If more than one photograph is shown for a certain species there will be explanations for each of them. Finally, section numbers of the phytochemical Chapters 3–8 are given, where the respective species are discussed. The individually combined occurrence of sec- ondary metabolites from different structural classes characterizes every species. However, it has to be remembered that a small number of citations does not neces- sarily indicate a poorer secondary metabolism in a respective species compared with others; this may just be due to less studies being carried out. Solanaceae Plate 1a Anthocercis littorea (yellow tailflower): erect or rarely sprawling shrub (to 3 m); W- and SW-Australia; Sects. 3.1 / 3.4 Plate 1b, c Atropa belladonna (deadly nightshade): erect herbaceous perennial plant (to 1.5 m); Europe to central Asia (naturalized: N-USA; cultivated as a medicinal plant); b fruiting twig; c flowers, unripe (green) and ripe (black) berries; Sects. 3.1 / 3.3.2 / 3.4 / 3.5 / 6.5.2 / 7.5.1 / 7.7.2 / 7.7.4.3 Plate 1d Brugmansia versicolor (angel’s trumpet): shrub or small tree (to 5 m); tropical parts of Ecuador west of the Andes (cultivated as an ornamental in tropical and subtropical regions); Sect. -

CORRELATION BETWEEN METABOLITE PROFILE and PHYTOCHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS of Ipomoea Aquatica Forssk

UNIVERSITI PUTRA MALAYSIA CORRELATION BETWEEN METABOLITE PROFILE AND PHYTOCHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. WITH ITS ANTIOXIDANT AND α-GLUCOSIDASE INHIBITORY ACTIVITIES USING NMR-BASED METABOLOMICS UMAR LAWAL FSTM 2016 4 CORRELATION BETWEEN METABOLITE PROFILE AND PHYTOCHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. WITH ITS ANTIOXIDANT AND α-GLUCOSIDASE INHIBITORY ACTIVITIES USING NMR-BASED METABOLOMICS UPM By UMAR LAWAL COPYRIGHT Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia, in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy © March 2016 All material contained within the thesis, including without limitation text, logos, icons, photographs and all other artwork, is copyright material of Universiti Putra Malaysia unless otherwise stated. Use may be made of any material contained within the thesis for non-commercial purposes from the copyright holder. Commercial use of material may only be made with the express, prior, written permission of Universiti Putra Malaysia. Copyright © Universiti Putra Malaysia. UPM COPYRIGHT © DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my parents and family UPM COPYRIGHT © Abstract of thesis presented to the Senate of Universiti Putra Malaysia in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy CORRELATION BETWEEN METABOLITE PROFILE AND PHYTOCHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. WITH ITS ANTIOXIDANT AND α-GLUCOSIDASE INHIBITORY ACTIVITIES USING NMR-BASED METABOLOMICS By UMAR LAWAL March 2016 UPM Chairman : Associate Professor Faridah Abas, PhD Faculty : Food Science and Technology Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. (morning glory) is a green leafy vegetable that is rich in minerals, proteins, vitamins, amino acids and secondary metabolites. The aims of the study were to discriminate Ipomoea extracts by 1H NMR spectroscopy in combination with chemometrics method and to determine their antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities. -

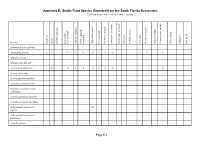

MSRP Appendix E

Appendix E. Exotic Plant Species Reported from the South Florida Ecosystem. Community types are indicated where known Species High Pine Scrub Scrubby high pine Beach dune/ Coastal strand Maritime hammock Mesic temperate hammock Tropical hardwood Pine rocklands Scrubby flatwoods Mesic pine flatwoods Hydric pine flatwoods Dry prairie Cutthroat grass Wet prairie Freshwater marsh Seepage swamp Flowing water swamp Pond swamp Mangrove Salt marsh Abelmoschus esculentus Abrus precatorius X X X X X X X X X X X X Abutilon hirtum Abutilon theophrasti Acacia auriculiformis X X X X X X X X X Acacia retinoides Acacia sphaerocephala Acalypha alopecuroidea Acalypha amentacea ssp. wilkesiana Acanthospermum australe Acanthospermum hispidum Achyranthes aspera var. X aspera Achyranthes aspera var. pubescens Acmella pilosa Page E-1 Species High Pine Scrub Scrubby high pine Beach dune/ Coastal strand Maritime hammock Mesic temperate hammock Tropical hardwood Pine rocklands Scrubby flatwoods Mesic pine flatwoods Hydric pine flatwoods Dry prairie Cutthroat grass Wet prairie Freshwater marsh Seepage swamp Flowing water swamp Pond swamp Mangrove Salt marsh Acrocomia aculeata X Adenanthera pavonina X X Adiantum anceps X Adiantum caudatum Adiantum trapeziforme X Agave americana Agave angustifolia cv. X marginata Agave desmettiana Agave sisalana X X X X X X Agdestis clematidea X Ageratum conyzoides Ageratum houstonianum Aglaonema commutatum var. maculatum Ailanthus altissima Albizia julibrissin Albizia lebbeck X X X X X X X Albizia lebbeckoides Albizia procera Page -

Appendix 9.2 Plant Species Recorded Within the Assessment Area

Appendix 9.2: Plant Species Recorded within the Assessment Area Agricultural Area Storm Water Fishponds Mudflat / Native/ Developed Distribution in Protection Village / Drain / Natural Modified and Coastal Scientific Name Growth Form Exotic to Area / Plantation Grassland Shrubland Woodland Marsh Mangrove Hong Kong (1) Status Orchard Recreational Watercourse Watercourse Mitigation Water Hong Kong Wasteland Dry Wet Pond Ponds Body Abrus precatorius climber: vine native common - + subshrubby Abutilon indicum native restricted - ++ herb Acacia auriculiformis tree exotic - - ++++ +++ + ++++ ++ +++ Acacia confusa tree exotic - - ++++ + +++ ++ ++ ++++ ++ ++++ Acanthus ilicifolius shrub native common - + ++++ Acronychia pedunculata tree native very common - ++ Adenosma glutinosum herb native very common - + + Adiantum capillus-veneris herb native common - + ++ ++ Adiantum flabellulatum herb native very common - + +++ +++ shrub or small Aegiceras corniculatum native common - +++ tree Aeschynomene indica shrubby herb native very common - + Ageratum conyzoides herb exotic common - ++ ++ ++ ++ ++ + Ageratum houstonianum herb exotic common - ++ + Aglaia odorata shrub exotic common - +++ + +++ + Aglaonema spp. herb - - - + + rare (listed under Forests and Ailanthus fordii (3) small tree native + Countryside Ordinance Cap. 96) Alangium chinense tree or shrub native common - ++ + ++ + +++ + Albizia lebbeck tree exotic - - +++ Alchornea trewioides shrub native common - + Aleurites moluccana tree exotic common - +++ ++ ++ ++ Allamanda cathartica climbing -

Convolvulaceae1

Photograph: Helen Owens © Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Government of South Australia Department of All rights reserved Environment, Copyright of illustrations might reside with other institutions or Water and individuals. Please enquire for details. Natural Resources Contact: Dr Jürgen Kellermann Editor, Flora of South Australia (ed. 5) State Herbarium of South Australia PO Box 2732 Kent Town SA 5071 Australia email: [email protected] Flora of South Australia 5th Edition | Edited by Jürgen Kellermann CONVOLVULACEAE1 R.W. Johnson2 Annual or perennial herbs or shrubs, often with trailing or twining stems, or leafless parasites; leaves alternate, exstipulate. Inflorescence axillary, rarely terminal, cymose or reduced to a single flower; flowers regular, (4) 5 (6)-merous, bisexual; sepals free or rarely united, quincuncial; corolla sympetalous, funnel-shaped or campanulate, occasionally rotate or salver-shaped; stamens adnate to the base of the corolla, alternating with the corolla lobes, filaments usually flattened and dilated downwards; anthers 2-celled, dehiscing longitudinally; ovary superior, mostly 2-celled, occasionally with 1, 3 or 4 cells, subtended by a disk; ovules 2, rarely 1, in each cell; styles 1 or 2, stigmas variously shaped. Fruit capsular. About 58 genera and 1,650 species mainly tropical and subtropical; in Australia 20 genera, 1 endemic, with c. 160 species, 17 naturalised. The highly modified parasitic species of Cuscuta are sometimes placed in a separate family, the Cuscutaceae. 1. Yellowish leafless parasitic twiners ...................................................................................................................... 5. Cuscuta 1: Green leafy plants 2. Ovary distinctly 2-lobed; styles 2, inserted between the lobes of ovary (gynobasic style); leaves often kidney-shaped ............................................................................................................. -

Dense Wild Yam Patches Established by Hunter-Gatherer Camps: Beyond the Wild Yam Question, Toward the Historical Ecology of Rainforests

Hum Ecol DOI 10.1007/s10745-013-9574-z Dense Wild Yam Patches Established by Hunter-Gatherer Camps: Beyond the Wild Yam Question, Toward the Historical Ecology of Rainforests Hirokazu Yasuoka # The Author(s) 2013. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Introduction Hladik and Dounias (1993), and Sato (2001, 2006) argued that for the Aka and Baka in the western Congo Basin Prior to the 1980s, most researchers believed that the African enough wild yams existed for their subsistence. These stud- forest hunter-gatherers, or Pygmies, were the original inhabitants ies were principally based on investigations of the density of of the central African rainforests. It was assumed that their close wild yams, and lacked detailed descriptions of the use of social, economic, and ecological relationships with neighboring wild yams. Therefore, the issue of whether exploitation of agricultural societies did not date back long, and that they had wild yams, including searching for them, digging them up, previously lived solely through foraging wild forest products. transporting them to the camp, and cooking and consuming The same is true for forest hunter-gatherers on other continents. them, could have been practiced in everyday life remains However, Headland (1987) and Bailey et al.(1989)noted inconclusive (cf. Bailey and Headland 1991). that no previous studies had produced sound evidence that pure Archaeological studies have provided powerful evidence hunter-gatherer subsistence was possible in any rainforests indicating the existence of humans in the African rainforests worldwide, and they argued that it was not, and had never been, before the beginning of agriculture (Mercader 2003a, b; possible to live in such areas while solely depending on wild Mercader and Martí 2003). -

Diversity of Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) in Some of the Regions of Maharashtra

Int. J. of Life Sciences, Special Issue A3 | September, 2015 ISSN: 2320-7817 |eISSN: 2320-964X RESEARCH ARTICLE Diversity of Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) in some of the regions of Maharashtra Undirwade DN1, BhadaneVV2 and Baviskar PS 1B.P. Arts, S.M.A. Science & K.K.C. Commerce. College, Chalisgaon, Dist.-Jalgaon, Maharshtra, India 2Pratap College, Amalner, Dist.-Jalgaon, Maharshtra, India * Corresponding author Email: [email protected] Manuscript details: ABSTRACT Available online on The present study deals with genus Ipomoea of family Convolvulaceaefrom http://www.ijlsci.in various regions of Maharashtra state. A total of 17 species of the genus have been collected from various localities of state Maharashtra on the collections ISSN: 2320-964X (Online) made between 2013 and 2015 from different parts. The present paper ISSN: 2320-7817 (Print) illustrates the diversity and morphology of the species of Ipomoea, which are separated from each other on the basis of their morphological characters. Editor: Dr. Arvind Chavhan Keywords: Diversity, Ipomoea, Convolvulaceae, Maharashtra. Cite this article as: Undirwade DN, Bhadane VV and Baviskar PS (2015) Diversity of Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) in some of INTRODUCTION the regions of Maharashtra, International J. of Life Sciences, The family Convolvulaceae is known as morning glory family. About Special issue, A3: 136-139. 2000 species of 58 genera are distributed overall the world, mainly in the tropics and subtropics region (Staple and Yang, 1998). More than one third of Copyright: © Author, This is the species are included into major genera Ipomoea and Convolvulus an open access article under (Conquist, 1988). Genus Ipomoea represented by 650 species distributed the terms of the Creative worldwide (Mabberley, 1997). -

Ipomoea Imperati Ipomoea Pes-Caprae Subsp.Brasiliensis

SGEB-75-12 Ipomoea imperati Ipomoea pes-caprae subsp. brasiliensis beach morning-glory railroad vine Convolvulaceae Both species have been reported to occur there. These plants occur in beach dunes and are important sand stabilizers and colonizers after disturbances. The seeds are important forage for several types of wildlife, including endangered beach mice. General Description Both species are stoloniferous, scrambling, creeping perennial vines that reach extreme lengths, upward of 30 ft or more. Leaves are simple and alternately arranged, with or without lobes. They have elongated petioles. Stems are trailing, fleshy, and glabrous, forming roots at nodes. Inflorescences are solitary and axillary. Sepals are coria- ceous, glabrous, or pubescent, and corollas are funnelform to campanulate (funnel to bell shaped) with 5 stamens and Credit: Gabriel Campbell, UF/IFAS the style included in the corolla. Interestingly, railroad vine flowers only last one day. Fruits are dry, dehiscent capsules Two species of Ipomoea are found in coastal beach plant with 4 large seeds. communities of the Florida Panhandle; beach morning-glo- ry (Ipomoea imperati) and railroad vine (Ipomoea pes-caprae Propagation subsp. brasiliensis). Beach morning-glory and railroad The authors propagate beach vine are distinguished by the colors of their corollas and morning-glory stem cuttings the shapes of their leaves. Beach morning-glory flowers without the application of are white with yellow and purple in the throat and leaves auxins. Single- or multi- are elliptical and notched; whereas railroad vine has a pink ple-node stem cuttings can to purple flower and kidney-shaped leaves. Beach morn- be taken along any portion ing-glory flowers occur from spring to fall, while railroad of the stem. -

BID Africa 2017 – Small Grant Template Final Narrative Report

<BID project id> <Start and end date of the reporting period> BID Africa 2017 – Small Grant Template Final narrative report Instructions Fill the template below with relevant information. please indicate the reason of the delay and expected date of completion. Use the information included in your project Full proposal (reproduced in annex III of your BID contract) as a baseline from which to complete this template The information provided below must correspond to the financial information that appears in the financial report Sources of verification are for example direct links to relevant digital documents, news/newsletters, brochures, copies of agreements with data holding institutions, workshop related documents, pictures, etc. Please provide access to all mentioned sources of verification by either providing direct link or sending a copy of the documents. This report must first be sent as a Word document to [email protected] and be pre-approved by GBIFS Once this report is pre-approved in writing by GBIFS, it must be signed by the BID project coordinator and sent by post to: The Global Biodiversity Information Facility Secretariat (GBIFS) Universitetsparken 15 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø Denmark Template 1. Table of Contents 1. Table of Contents ...................................................................................................... 1 2. Project Information..................................................................................................... 3 3. Overview of results ................................................................................................... -

Plant Production--Root Vegetables--Yams Yams

AU.ENCI FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVILOPME4T FOR AID USE ONLY WASHINGTON. 0 C 20823 A. PRIMARYBIBLIOGRAPHIC INPUT SHEET I. SUBJECT Bbliography Z-AFOO-1587-0000 CL ASSI- 8 SECONDARY FICATIDN Food production and nutrition--Plant production--Root vegetables--Yams 2. TITLE AND SUBTITLE A bibliography of yams and the genus Dioscorea 3. AUTHOR(S) Lawani,S.M.; 0dubanjo,M.0. 4. DOCUMENT DATE IS. NUMBER OF PAGES 6. ARC NUMBER 1976 J 199p. ARC 7. REFERENCE ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS IITA 8. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES (Sponaoring Ordanization, Publlahera, Availability) (No annotations) 9. ABSTRACT This bibliography on yams bring together the scattered literature on the genus Dioscorea from the early nineteenth century through 1975. The 1,562 entries in this bibliography are grouped into 36 subject categories, and arranged within each category alphabetically by author. Some entries, particularly those whose titles are not sufficiently informative, are annotated. The major section titles in the book are as follows: general and reference works; history and eography; social and cultural importance; production and economics; botany including taxonomy, genetics, and breeding); yam growing (including fertilizers and plant nutrition); pests and diseases; storage; processing; chemical composition, nutritive value, and utilization; toxic and pharmacologically active constituents; author index; and subject index. Most entries are in English, with a few in French, Spanish, or German. 10. CONTROL NUMBER I1. PRICE OF DOCUMENT PN-AAC-745 IT. DrSCRIPTORS 13. PROJECT NUMBER Sweet potatoes Yams 14. CONTRACT NUMBER AID/ta-G-1251 GTS 15. TYPE OF DOCUMENT AID 590-1 44-741 A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF YAMS AND THE GENUS DIOSCOREA by S.