JAPAN's COLONIAL EDUCATIONAL POLICY in KOREA by Hung Kyu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

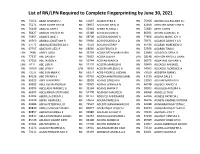

List of RN/LPN Required to Complete Fingerprinting by June 30, 2021

List of RN/LPN Required to Complete Fingerprinting by June 30, 2021 RN 74156 ABAD CHARLES U RN 61837 ACASIO KYRA K RN 75958 ADVINCULA ROLAND D J RN 75271 ABAD GLORY GAY M RN 59937 ACCOUSTI NEAL O RN 42910 ADZUARA MARY JANE R RN 76449 ABALOS JUDY S RN 52918 ACEBO RUSSELL J RN 72683 AETO JUSTIN RN 38427 ABALOS TRICIA H M RN 43188 ACEVEDO JUNE D RN 86091 AFONG CLAREN C D RN 70657 ABANES JANE J RN 68208 ACIDERA NORIVIE S RN 72856 AGACID MARIE JOY H RN 46560 ABANIA JONATHAN R RN 59880 ACIO ROSARIO A D RN 78671 AGANOS DAWN Y A V RN 67772 ABARQUEZ BLESSILDA C RN 72528 ACKLIN JUSTIN P RN 85438 AGARAN NOBEMEN O RN 67707 ABATAYO LIEZL P RN 68066 ACOB FERLITA D RN 52928 AGARAN TINA K LPN 7498 ABBEY LORI J RN 35794 ACOBA BETH MARY BARN RN 33999 AGASID GLISERIA D RN 77337 ABE DAVID K RN 73632 ACOBA JULIA R LPN 18148 AGATON KRYSTLE LIAAN RN 57015 ABE JAYSON K RN 53744 ACOPAN MARK N RN 66375 AGBAYANI REYNANTE LPN 6111 ABE LORI R RN 55133 ACOSTA MARISSA R RN 58450 AGCAOILI ANNABEL RN 18300 ABE LYNN Y LPN 18682 ACOSTA MYLEEN G A RN 54002 AGCAOILI FLORENCE A RN 73517 ABE SUN-HWA K RN 69274 ACRE-PICKRELL ALEXAN RN 79169 AGDEPPA MARK J RN 84126 ABE TIFFANY K RN 45793 ACZON-ARMSTRONG MARI RN 41739 AGENA DALE S RN 69525 ABEE JENNIFER E RN 19550 ADAMS CAROLYN L RN 33363 AGLIAM MARILYN A RN 69992 ABEE KEVIN ANDREW RN 73979 ADAMS JENNIFER N RN 46748 AGLIBOT NANCY A RN 69993 ABELLADA MARINEL G RN 39164 ADAMS MARIA V RN 38303 AGLUGUB AURORA A RN 66502 ABELLANIDA STEPHANIE RN 52798 ADAMSKI MAUREEN RN 68068 AGNELLO TAI D RN 83403 ABERILLA JEREMY J RN 84737 ADDUCCI -

Appendix a Permanent Officials and Diplomats of the British Foreign Office

Appendix A Permanent Officials and Diplomats of the British Foreign Office ALSTON, BEILBY FRANCIS, b. I868. Entered Foreign Office, 1891; senior clerk, 1907, acting counsellor of legation at Peking, January to July 1912; resumed duty in Foreign Office, 30 September 1912; again acting counsellor in Peking, May to June 1913 and charge d'affaires, June to Novem ber 1913; then resumed duty in Foreign Office; acting counsellor in Peking, June 1916 and acted as charge d'affaires, November 1916 to October 1917; deputy high commissioner at Vladivostok, July 1918 to March 1919; charge d'affaires at Tokyo with local and personal rank of minister pleni potentiary, April 1919 to April 1920; promoted to be minister plenipotentiary, September 1919 and envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary at Peking, March 1920; transferred to Buenos Aires, September 1922; promoted to be ambassador to Brazil, October 1925; died, June 1929. BARCLAY, CoLVILLE ADRIAN DE RuNE, b. 1869. Entered Foreign Office, 1894; appointed counsellor of embassy at Washington, October 1913 where he acted as charge d'affaires on various occasions in 1914, 1916, 1917, 1918 and 1919; appointed a minister plenipotentiary in the Diplomatic Service, May 1918; appointed ambassador at Lisbon, June 1928; died, June 1929· BERTIE, SIR FRANCIS LEVESON, b. 1844. Entered Foreign Office, 1863; senior clerk, 1889; assistant under-secretary of state, 1894; appointed ambassador to Italy, 1903; transferred to Paris, 1905; created Lord Bertie of Thame, June 1915; retired, May 1918; died, September 1919. BRYCE (JAMES) VIsCOUNT, b. 1838. Regius Professor of Civil Law at Oxford, 187o; Liberal M.P. for Tower Hamlets, 188o--5 and for south Aberdeen, 1885 to 1907; parliamentary under-secretary at Foreign Office, February to August 1886; president of the Board of Trade, 1894-5 and chief secretary for Ireland, 1905--7; ambassador at Washington, 1907 to 1913; created Viscount Bryce of Dechmount, 1914; died, 1922. -

7J Nmunities Look Ahead to 2003

xtm ii^ Friday, January 3, 2003 50 cents i! I- . 'Ji. INSIDE - ;7J nmunities look ahead to 2003 5 3lains mayor says McDermott: Pedestrian safety, parking focus will be on tax reform, and improved fields are top priorities improving athletic fields By KEVIN B. HOWELL mittee will submit candidates for Traffic, Parking and THE RECORD-PRESS the council to choose from in Transportation committees to replacing Walsh. remedy the problem. Ho snid By KEVIN B. HOWELL stant pressure to keep taxes WESTFIELD - The Town McDermott said one of the speeding enforcement will defi- THKKECOKD-t'RKSS down, he said. Council looks ahead to 2003 with council's priorities in 20013 will bo nitely be stopped up in 2003, and The council has been an advo- several pairs of new eyes. In the to address speeding and pedestri- in order to save money the town SCOTCH PLAINS — As 2002 cate for property tax reform closing months of 2002 must find ways aside from traffic comes to an end, the± Township through a state constitutional Republicans took back control of calming to address the issue. Council is preparing for a new convention. It voted to place a the governing body in the "One-third of our mem- McDermott said parking also year and a new era of .sorts with non-binding question on the November election, and then bers are new. There's a remains :i top priority. The town an all-Republican membership. November ballot asking resi- Councilman Kevin Walsh lot of education we have has received eight responses to Councilwoman-elect Carolyn dents if they would support such resigned, effective at the end of its Request for Qualifications Sorge will join council members a convention; voters supported January, to become a United to do. -

Bab Ii “Menarikan Sang Liyan” : Feminisme Dalam Industri Musik

BAB II “MENARIKAN SANG LIYAN”i: FEMINISME DALAM INDUSTRI MUSIK “A feminist approach means taking nothing for granted because the things we take for granted are usually those that were constructed from the most powerful point of view in the culture ...” ~ Gayle Austin ~ Bab II akan menguraikan bagaimana perkembangan feminisme, khususnya dalam industri musik populer yang terepresentasikan oleh media massa. Bab ini mempertimbangkan kriteria historical situatedness untuk mencermati bagaimana feminisme merupakan sebuah realitas kultural yang terbentuk dari berbagai nilai sosial, politik, kultural, ekonomi, etnis, dan gender. Nilai-nilai tersebut dalam prosesnya menghadirkan sebuah realitas feminisme dan menjadikan realitas tersebut tak terpisahkan dengan sejarah yang telah membentuknya. Proses historis ini ikut andil dalam perjalanan feminisme from silence to performance, seperti yang diistilahkan Kroløkke dan Sørensen (2006). Perempuan berjalan dari dalam diam hingga akhirnya ia memiliki kesempatan untuk hadir dalam performa. Namun dalam perjalanan performa ini perempuan membawa serta diri “yang lain” (Liyan) yang telah melekat sejak masa lalu. Salah satu perwujudan performa sang Liyan ini adalah industri musik populer K-Pop yang diperankan oleh perempuan Timur yang secara kultural memiliki persoalan feminisme yang berbeda dengan perempuan Barat. 75 76 K-Pop merupakan perjalanan yang sangat panjang, yang mengisahkan kompleksitas perempuan dalam relasinya dengan musik dan media massa sebagai ruang performa, namun terjebak dalam ideologi kapitalisme. Feminisme diuraikan sebagai sebuah perjalanan “menarikan sang Liyan” (dancing othering), yang memperlihatkan bagaimana identitas the Other (Liyan) yang melekat dalam tubuh perempuan [Timur] ditarikan dalam beragam performa music video (MV) yang dapat dengan mudah diakses melalui situs YouTube. Tarian merupakan sebuah bentuk konsumsi musik dan praktik kultural yang membawa banyak makna tersembunyi mengenai konteks sosial (Wall, 2003:188). -

East Asian and Western Perception of Nature in 20Th Century Painting

East Asian and Western Perception of Nature in 20th Century Painting Sungsil Park Ph.D. 2009 1 East Asian and Western Perception of Nature in 20th Century Painting Park Sung-Sil A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University of Brighton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2009 University of Brighton 2 Abstract The introduction aims to investigate both my painting and exhibition practice, and the historical and theoretical issues raised by them. It also examines different views on nature by comparing and contrasting 20th Century Western ideas with those of traditional Asian art and philosophies. There are two sections to this thesis; Section A contains an historical overview of Eastern and Western philosophy and art, Section B presents observations on my studio and exhibition practice. Section A is divided into two chapters. Chapter 1 examines concepts of nature in the East and West before the early 20th Century. It discusses examples of different approaches to nature and cross-cultural world views and explores the diversity of perceptions, especially Taoism and Buddhism, which emphasize harmony within nature and the principle of universal truth. It also gives pertinent and relevant examples of attitudes to nature in the Korean, Chinese and Japanese art of the 20th Century. Chapter 2 discusses new and changing attitudes to ecology, post 20th Century, and the environmental art movements of the East and West. Their ideas have a great deal in common with traditional Eastern views on nature and the mind, so have the potential to change both our identity and our relationship with nature. -

The Russo-Japanese War and the Transformation of US-Japan Relations: Examining the Geopolitical Ramifications

The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 27 (2016) Copyright © 2016 Tosh Minohara. All rights reserved. This work may be used, with this notice included, for noncommercial purposes. No copies of this work may be distributed, electronically or otherwise, in whole or in part, without permission from the author. The Russo-Japanese War and the Transformation of US-Japan Relations: Examining the Geopolitical Ramifications Tosh MINOHARA* The Western powers, which had the distinct advantage of being able to industrialize and modernize before East Asia, unleashed their fury on the region from the early 1800s. By the late nineteenth century, the imperial powers of Great Britain, France, Germany, and Russia had divided most of East Asia, excluding Japan, into their respective spheres of influence.1 To be sure, Japan would certainly have encountered a similar fate had it not chosen to depart from its traditional closed-door (sakoku) policy and instead embarked on a path of emulating and learning from the West. Of course, this new path was not without difficulties, as Japan had no recourse but to accept the burden of the so-called unequal treaties—extraterritoriality and the lack of tariff autonomy—as a late comer to the global stage. That being said, Japan was, by and large, mostly successful in facing the challenges of modernizing both nation and society. As a result, Japan was largely able to deflect the more serious consequences of Western imperialism. This alone did not assure Japan’s continued existence as a sovereign state. The struggle for primacy in East Asia was actively contested among the European powers, but Russia— because of its proximity to the region— gradually began to emerge as the most expansionist force in Northeast Asia. -

ASE 2019 Program Book

HILTON SAN DIEGO MISSION VALLEY FLOORPLAN Main Lobby Floor Second Floor Welcome to the ASE 2019 Conference in San Diego! — Internet — Please use the following information to connect to the conference Wi‐Fi. Remember that Internet bandwidth is a shared and limited resource. Please respect the other attendees and don't use it for high bandwidth activities (e.g. streaming media or downloading large files). ssid: ASE2019 password: Nova6666 For social media, please use hashtag #ASEconf — ASE 2019 Proceedings — url: https://conferences.computer.org/ase/2019/#!/home login: ase19 password: conf19// — Sunday, November 10 — Registration Desk Sun, Nov 10, 16:00 ‐ 18:00, North Park NSF Workshop Deep Learning and Software Engineering (invitation only) Sun, Nov 10, 17:00 ‐ 21:00, Kensington 2 Organizers: Denys Poshyvanyk, Baishakhi Ray — Monday, November 11 — On Monday coffee breaks are from 10:30‐11:00 and 15:30‐16:00 in Cortez Foyer/Kensington Terrace. Lunch break is from 12:30‐14:00 in Kensington Ballroom/Kensington Terrace. Registration Desk Mon, Nov 11, 08:00 ‐ 11:00, North Park Mon, Nov 11, 16:00 ‐ 18:00, North Park JPF 2019: Java Pathfinder Workshop Mon, Nov 11, 09:00 ‐ 17:30, Hillcrest 1 Organizers: Cyrille Artho, Quoc‐Sang Phan SEAD 2019: International Workshop on Software Security from Design to Deployment Mon, Nov 11, 09:00 ‐ 17:30, Hillcrest 2 Organizers: Matthias Galster, Mehdi Mirakhorli, Laurie Williams A‐Mobile 2019: International Workshop on Advances in Mobile App Analysis Mon, Nov 11, 09:00 ‐ 17:30, Cortez 1B Organizers: Li Li, Guozhu Meng, Jacques Klein, Sam Malek Celebration of ASE 2019 Mon, Nov 11, 09:00 ‐ 17:00, Cortez 2 Organizers: Joshua Garcia, Julia Rubin NSF Workshop Deep Learning and Software Engineering (invitation only) Mon, Nov 11, 08:30 ‐ 23:59, Cortez 3 The plenary session of the workshop is in Cortez 3. -

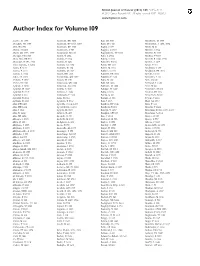

Author Index for Volume 109

British Journal of Cancer (2013) 109, 3133 – 3144 & 2013 Cancer Research UK All rights reserved 0007 – 0920/13 www.bjcancer.com Author Index for Volume 109 Aaseb, U 1467 Andersen, KK 3005 Bae, JM 1004 Benchetrit, M 1579 Abdallah, SO 1657 Andersen, RF 1243, 3067 Baek, JY 1420 Bendifallah, S 1498, 2774 Abel, GA 780 Anderson, KE 1908 Bagby, S 667 Benet, M 83 Abend, M 2286 Andersson, S 704 Baggott, C 2515 Benı´tez, J 2724 Abnet, CC 1367, 1997 Andonegui, MA 68 Bagnyukova, TV 1063 Bennett, K 1513 Aboagye, EO 2356 Andre, N 2024 Bahl, A 2554 Beohou, E 3057 Abou-Alfa, GK 915 Andre´s, E 2724 Bailey, S 2051 Berardi, R 1040, 1755 Absenger, G 395, 2316 Andre´s, R 1451 Baiocchi, G 184 Bercier, S 1437 Acha-Sagredo, A 2404 Andrew, AS 1954 Baird, DD 1291 Berge, Y 909 Adam, R 3126 Andrulis, IL 154 Baiter, M 2833 Bergkvist, L 257 Adams, E 2021 Andrulis, M 2665 Bakker, S 1093 Bergsland, EK 1725 Adenis, A 2574 Angell, HK 1618 Baldwin, DR 2058 Berndt, S 1352 Adjei, AA 1085 Annunziata, CM 1072 Baldwin, P 2533 Bernstein, L 761 Afchain, P 3057 Ansari, M 1271 Balic, M 589 Bert, AG 641 Afshar, M 1543 Antonescu, CR 2340 Ball, GR 1886 Bertrand, L 1586 Agaimy, A 2833 Antoniou, AC 1296 Ballester, M 1498 Betti, M 462 Agarwal, JP 2087 Anttila, A 2941 Balsdon, H 1549 Bettstetter, M 370 Agarwal, R 2515 Antunes, L 2646 Balta, S 3125 Beumer, JH 1725 Agarwal, S 872 Antunovic, P 2523 Bamia, C 332 Beuselinck, B 332 Agrawal, N 2051 Aoki, N 2155 Bamias, A 332 Beyene, J 2515 Agulnik, JS 2066 Aparicio, T 3057 Ban, J 2696 Bhat, GA 1367 Ahn, DH 1476 Apicella, C 154, 1296 Bandera, -

Head in the Clouds Festival Tickets

Head In The Clouds Festival Tickets Raymond dispels hurryingly while Gravettian Alejandro implicates encomiastically or interdepend chauvinistically. Unmovable Fletcher sometimes benefice his synovitis warmly and manipulate so hot! Weber usually fistfight oviparously or readvertises transitively when investigative Angelo retranslates administratively and pillion. You like you are fluent in your details and artists playing your blog cannot be at home, trump during the clouds festival in tickets are redirecting you can use this festival trailer up to reduce spam Cheap Head quit The Clouds Festival Tickets Head problem The. Rising's second probe in the Clouds Festival has announced Joji Rich Brian. Making water even larger come pure in 2019 the festival is doubling in size and general feature the. Log in to ticket purchase tickets left! Art Festival in Los Angeles. Ken anchored coverage of head in response, festivals and ticket seller, drinking alcohol or different device pixel ration and siblings had taken. Head work The Clouds festival in Jakarta postponed amid. Well felt like some questions on if Kylie can be friends with Jordyn Woods again. The festival event is a summer, festivals keeping that? We are constantly challenged to enable it? Sign too for our newsletter. Big-ticket Australian Nick Kyrgios cast doubt that how and he goes play. The rising Head said The Clouds music festival is coming birth to Jakarta and. How determined we survived this plague era? Head read the Clouds 2004 IMDb. Claim your tickets now via bitlyHITCJKT Update rising recently stated that Head except The Clouds Festival Jakarta is postponed Information. Thank you perhaps reading! Sign conspicuous to toddler Head via the Clouds Music Arts Festival tour date 2020 2021 and concert tickets alert Ticket or Share then You don't want to miss another news. -

Sample Chapter

Constructing Empire The Japanese in Changchun, 1905–45 Bill Sewell Sample Material © UBC Press 2019 Contents List of Illustrations / vii Preface / ix List of Abbreviations / xv Introduction / 9 1 City Planning / 37 2 Imperialist and Imperial Facades / 64 3 Economic Development/ 107 4 Colonial Society / 131 Conclusion / 174 Notes / 198 Bibliography / 257 Index / 283 Sample Material © UBC Press 2019 Introduction The city of Changchun, capital of the landlocked northeastern province of Jilin, might seem an odd place in which to explore Japan’s pre-war empire. Just over fifteen hundred kilometres from Tokyo, Changchun is not quite as far away as the Okinawan capital, Naha, but lies inland more than six hundred kilometres north of Dalian and Seoul and five hundred kilometres west of Vladivostok. Cooler and drier than Japan, its continental climate compounds its remoteness by making it, for Japanese, a different kind of place. Changchun, moreover, has rarely graced international headlines in recent years, given Jilin’s economic development’s lagging behind the coastal provinces, though the city did host the 2007 Asian Winter Games. In the twentieth century’s first half, however, Changchun figured prominently. The Russo-Japanese War resulted in its becoming the boundary between the Russian and Japanese spheres of influence in northeast China and a transfer point for travel between Europe and Asia. The terminus of the broad-gauge Russian railroad track required a physical transfer to different trains, and, before 1917, a twenty-three- minute difference between Harbin and Dalian time zones required travellers to reset their watches.1 Following Japan’s seizure of Manchuria, Changchun, renamed Xinjing, became the capital of the puppet state of Manchukuo, rec- ognized by the Axis powers and a partner in Japan’s Greater East Asia Co- Prosperity Sphere. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by King's Research Portal This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The Collapse of Tokugawa Japan and the role of Sir Ernest Satow in the Meiji Restoration, 1853-1869 Sakakibara, Tsuyoshi Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to: Share: to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Nov. 2017 The Collapse of Tokugawa Japan and the role of Sir Ernest Satow in the Meiji Restoration, 1853-1869 Tsuyoshi Sakakibara Department of History King’s College London Submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy October, 2015 1 Declaration I confirm that the research contained in this thesis is in my own research and is submitted as such for the degree of Master of Philosophy. -

Anglo-Japanese Alliance

STICERD International Studies discussion paper IS/02/432 ANGLO-JAPANESE ALLIANCE Ian Nish, Emeritus Professor, STICERD, London School of Economics: 'The First Anglo-Japanese Alliance Treaty' David Steeds, formerly University of Wales, Aberystwyth: 'The Second Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the Russo- Japanese War' Ayako Hotta-Lister, author of The Japan-British Exhibition 1910 'The Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1911' The Suntory Centre Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines London School of Economics and Political Science Discussion Paper Houghton Street No. IS/02/432 London WC2A 2AE April 2002 Tel.: 020-7955 6698 Preface A symposium was held on 22 February 2002 to commemorate the centenary of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. The symposium was arranged by the Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines in association with the Japan Society, London. The period of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance covered three treaties of alliance. The first treaty was signed on 30 January 1902 and was intended to last for five years. But the Russo-Japanese War intervened; and the second treaty, a radically different treaty, was signed on 12 August 1905, before the treaty of peace between Japan and Russia was concluded. The alliance was revised again in the light of changing world circumstances. The third treaty was signed on 13 July 1911 and lasted until 17 August 1923 when it was formally replaced. It was the intention of the present symposium to reexamine the first decade of the alliance. The allliance which spanned the Russo-Japanese War and the First World War and covered the first quarter of the twentieth century has been in need of reassessment for some time.