A Profile of Panhandling Black Bears in the Great Smoky Mountains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educator Packet

Educator Packet Animal Survival Strategies Grade Level: 4th Grade (can be adapted to 2nd and 3rd grade) Overview: Students will observe pieces of art from the Art and Animal exhibit and learn about various Ohio wildlife species and the ways they adapt to survive extremes in weather and environments. Materials: Wildlife board game and handout on animal traits. Content Standards: Science: Changes in an organism’s environment are sometimes beneficial to its survival and sometimes harmful. Plants and animals have life cycles that are part of their adaptations for survival in their natural environments. Organisms that survive pass on their traits to future generations Social Studies: Places and Regions: The regions of the United States known as the North, South and West developed in the early 1800s largely based on their physical environments and economies. Human Systems: People have modified the environment since prehistoric times. There are both positive and negative consequences for modifying the environment in Ohio and the United States. Background/Key Ideas: Students will play a game that includes reproductions of several pieces of art from the exhibit Art and the Animal. All pieces are images of animals that can be found in Ohio. Students will use previous knowledge and deductive reasoning to match the correct facts (classifications, and characteristics) to each animal. After completion of the game, facts about adaptation will be further addressed with a silly exercise where the classroom teacher is outfitted with various props which represent each of the animals from the game. Procedures: Introduction: “Hello and welcome to another round of Adapt to Survive; the game where you compete to match Ohio’s wildlife to the correct category. -

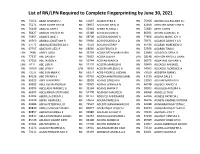

List of RN/LPN Required to Complete Fingerprinting by June 30, 2021

List of RN/LPN Required to Complete Fingerprinting by June 30, 2021 RN 74156 ABAD CHARLES U RN 61837 ACASIO KYRA K RN 75958 ADVINCULA ROLAND D J RN 75271 ABAD GLORY GAY M RN 59937 ACCOUSTI NEAL O RN 42910 ADZUARA MARY JANE R RN 76449 ABALOS JUDY S RN 52918 ACEBO RUSSELL J RN 72683 AETO JUSTIN RN 38427 ABALOS TRICIA H M RN 43188 ACEVEDO JUNE D RN 86091 AFONG CLAREN C D RN 70657 ABANES JANE J RN 68208 ACIDERA NORIVIE S RN 72856 AGACID MARIE JOY H RN 46560 ABANIA JONATHAN R RN 59880 ACIO ROSARIO A D RN 78671 AGANOS DAWN Y A V RN 67772 ABARQUEZ BLESSILDA C RN 72528 ACKLIN JUSTIN P RN 85438 AGARAN NOBEMEN O RN 67707 ABATAYO LIEZL P RN 68066 ACOB FERLITA D RN 52928 AGARAN TINA K LPN 7498 ABBEY LORI J RN 35794 ACOBA BETH MARY BARN RN 33999 AGASID GLISERIA D RN 77337 ABE DAVID K RN 73632 ACOBA JULIA R LPN 18148 AGATON KRYSTLE LIAAN RN 57015 ABE JAYSON K RN 53744 ACOPAN MARK N RN 66375 AGBAYANI REYNANTE LPN 6111 ABE LORI R RN 55133 ACOSTA MARISSA R RN 58450 AGCAOILI ANNABEL RN 18300 ABE LYNN Y LPN 18682 ACOSTA MYLEEN G A RN 54002 AGCAOILI FLORENCE A RN 73517 ABE SUN-HWA K RN 69274 ACRE-PICKRELL ALEXAN RN 79169 AGDEPPA MARK J RN 84126 ABE TIFFANY K RN 45793 ACZON-ARMSTRONG MARI RN 41739 AGENA DALE S RN 69525 ABEE JENNIFER E RN 19550 ADAMS CAROLYN L RN 33363 AGLIAM MARILYN A RN 69992 ABEE KEVIN ANDREW RN 73979 ADAMS JENNIFER N RN 46748 AGLIBOT NANCY A RN 69993 ABELLADA MARINEL G RN 39164 ADAMS MARIA V RN 38303 AGLUGUB AURORA A RN 66502 ABELLANIDA STEPHANIE RN 52798 ADAMSKI MAUREEN RN 68068 AGNELLO TAI D RN 83403 ABERILLA JEREMY J RN 84737 ADDUCCI -

Behavioral Patterns of Laboratory Mongolian Gerbils by Sex and Housing Condition: a Case Study with an Emphasis on Sleeping Patterns

Journal of Veterinary Behavior 30 (2019) 69e79 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Veterinary Behavior journal homepage: www.journalvetbehavior.com Small Mammal Research Behavioral patterns of laboratory Mongolian gerbils by sex and housing condition: a case study with an emphasis on sleeping patterns Camilo Hurtado-Parrado, PhD a,b,*, Ángelo Cardona-Zea, BSc b, Mónica Arias-Higuera, BSc b, Julián Cifuentes, BSc b, Alejandra Muñoz, MSc b, Javier L. Rico, PhD b, Cesar Acevedo-Triana, MSc c a Department of Psychology, Troy University, Troy, AL, USA b Faculty of Psychology, Fundación Universitaria Konrad Lorenz, Bogotá DC, Colombia c School of Psychology, Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, Tunja, Colombia article info abstract Article history: The behavioral patterns of Mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) housed individually and in same- Received 10 September 2018 sex groups (siblings) were characterized. Gerbils were continuously video-recorded 24 hours (day 1) and Accepted 7 December 2018 120 hours (day 5) after housing conditions were established (no environmental enrichment was Available online 13 December 2018 implemented). Video samples totaling 2016 minutes were scored to obtain measures of maintenance (drinking, sleeping, grooming, and eating), locomotor (jumping and rearing), communication (foot Keywords: stomping), and stereotyped behaviors (gnawing bar and digging), which were compared across housing case study conditions and sex. Irrespective of sex or housing, gerbils dedicated between 65 and 75% of the day to Mongolian gerbil Meriones unguiculatus maintenance behaviors; more than 50% of this time was dedicated to sleep. Time allocated to other d d housing conditions behavioral states for example, bar gnawing, digging, and eating remained below 5% of the observation captivity time. -

JAPAN's COLONIAL EDUCATIONAL POLICY in KOREA by Hung Kyu

Japan's colonial educational policy in Korea, 1905-1930 Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Bang, Hung Kyu, 1929- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 19:48:17 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565261 JAPAN'S COLONIAL EDUCATIONAL POLICY IN KOREA 1905 - 1930 by Hung Kyu Bang A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 2 (c)COPYRIGHTED BY HONG KYU M I G 19?2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by ___________ Hung Kvu Bang____________________________ entitled Japan's Colonial Educational Policy in Korea________ ____________________________________________________1905 - 1930_________________________________________________________________ be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of ______________ Doctor of Philosophy_____________________ 7! • / /. Dissertation Director Date After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:* M. a- L L U 2 - iLF- (/) C/_L±P ^ . This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination. The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. -

Lagomorphs: Pikas, Rabbits, and Hares of the World

LAGOMORPHS 1709048_int_cc2015.indd 1 15/9/2017 15:59 1709048_int_cc2015.indd 2 15/9/2017 15:59 Lagomorphs Pikas, Rabbits, and Hares of the World edited by Andrew T. Smith Charlotte H. Johnston Paulo C. Alves Klaus Hackländer JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS | baltimore 1709048_int_cc2015.indd 3 15/9/2017 15:59 © 2018 Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2018 Printed in China on acid- free paper 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www .press .jhu .edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Smith, Andrew T., 1946–, editor. Title: Lagomorphs : pikas, rabbits, and hares of the world / edited by Andrew T. Smith, Charlotte H. Johnston, Paulo C. Alves, Klaus Hackländer. Description: Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017004268| ISBN 9781421423401 (hardcover) | ISBN 1421423405 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781421423418 (electronic) | ISBN 1421423413 (electronic) Subjects: LCSH: Lagomorpha. | BISAC: SCIENCE / Life Sciences / Biology / General. | SCIENCE / Life Sciences / Zoology / Mammals. | SCIENCE / Reference. Classification: LCC QL737.L3 L35 2018 | DDC 599.32—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017004268 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Frontispiece, top to bottom: courtesy Behzad Farahanchi, courtesy David E. Brown, and © Alessandro Calabrese. Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or specialsales @press .jhu .edu. Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post- consumer waste, whenever possible. -

Bab Ii “Menarikan Sang Liyan” : Feminisme Dalam Industri Musik

BAB II “MENARIKAN SANG LIYAN”i: FEMINISME DALAM INDUSTRI MUSIK “A feminist approach means taking nothing for granted because the things we take for granted are usually those that were constructed from the most powerful point of view in the culture ...” ~ Gayle Austin ~ Bab II akan menguraikan bagaimana perkembangan feminisme, khususnya dalam industri musik populer yang terepresentasikan oleh media massa. Bab ini mempertimbangkan kriteria historical situatedness untuk mencermati bagaimana feminisme merupakan sebuah realitas kultural yang terbentuk dari berbagai nilai sosial, politik, kultural, ekonomi, etnis, dan gender. Nilai-nilai tersebut dalam prosesnya menghadirkan sebuah realitas feminisme dan menjadikan realitas tersebut tak terpisahkan dengan sejarah yang telah membentuknya. Proses historis ini ikut andil dalam perjalanan feminisme from silence to performance, seperti yang diistilahkan Kroløkke dan Sørensen (2006). Perempuan berjalan dari dalam diam hingga akhirnya ia memiliki kesempatan untuk hadir dalam performa. Namun dalam perjalanan performa ini perempuan membawa serta diri “yang lain” (Liyan) yang telah melekat sejak masa lalu. Salah satu perwujudan performa sang Liyan ini adalah industri musik populer K-Pop yang diperankan oleh perempuan Timur yang secara kultural memiliki persoalan feminisme yang berbeda dengan perempuan Barat. 75 76 K-Pop merupakan perjalanan yang sangat panjang, yang mengisahkan kompleksitas perempuan dalam relasinya dengan musik dan media massa sebagai ruang performa, namun terjebak dalam ideologi kapitalisme. Feminisme diuraikan sebagai sebuah perjalanan “menarikan sang Liyan” (dancing othering), yang memperlihatkan bagaimana identitas the Other (Liyan) yang melekat dalam tubuh perempuan [Timur] ditarikan dalam beragam performa music video (MV) yang dapat dengan mudah diakses melalui situs YouTube. Tarian merupakan sebuah bentuk konsumsi musik dan praktik kultural yang membawa banyak makna tersembunyi mengenai konteks sosial (Wall, 2003:188). -

The Carnivora of Madagascar

THE CARNIVORA OF MADAGASCAR 49 R. ALBIGNAC The Carizizrorn of Madagascar The carnivora of Madagascar are divided into 8 genera, 3 subfamilies and just one family, that of the Viverridae. All are peculiar to Madagascar except for the genus Viverricula, which is represented by a single species, Viverricula rasse (HORSFIELD),which is also found throughout southern Asia and was probably introduced to the island with man. Palaeontology shows that this fauna is an ancient one comprising many forms, which appear to be mainly of European origin but with very occasional kinships with the Indian region. For instance, Cvptofiroctaferox, although perhaps not directly related to Proailurus lenianensis (a species found in the phosphorites of the Quercy region of France and in the Aquitanian formations of Saint Gérand-le- Puy) , nevertheless appears to be the descendant of this line. Similarly, the origin of the Fossa and Galidiinae lines would seem to be close to that of the holarctic region. Only Eupleres raises a problem, having affinities with Chrotogale, known at present in Indochina. The likely springboard for these northern species is the continent of Africa. This archaic fauna has survived because of the conservative influence of the island, which has preserved it into modern times. In the classification of mammals G. G. SIMPSONputs the 7 genera of Madagascan carnivora in the Viverridae family and divides them into 3 subfamilies, as shown in the following table : VIVERRIDAE FAMILY Fossinae subfamily (Peculiar to Madagascar) Fossa fossa (Schreber) Eupleres goudotii Doyère Galidiinae subfamily (peculiar to Madagascar) Galidia elegans Is. Geoffroy Calidictis striata E. Geoffroy Mungotictis lineatus Pocock Salanoia concolor (I. -

Effect of Behavioural Feedback on Circadian Clocks of the Nocturnal Field Mouse Mus Booduga R

This article was downloaded by: [Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Adv. Sci. Research] On: 20 January 2012, At: 03:12 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Biological Rhythm Research Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/nbrr20 Effect of Behavioural Feedback on Circadian Clocks of the Nocturnal Field Mouse Mus booduga R. Chidambaram a , G. Marimuthu a & Vijay Kumar Sharma b a Department of Animal Behaviour and Physiology, School of Biological Sciences Madurai Kamaraj University Madurai Tamil Nadu India b Chronobiology Laboratory, Evolutionary and Organismal Biology Unit Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research, Jakkur Bangalore Karnataka India Available online: 09 Aug 2010 To cite this article: R. Chidambaram, G. Marimuthu & Vijay Kumar Sharma (2004): Effect of Behavioural Feedback on Circadian Clocks of the Nocturnal Field Mouse Mus booduga , Biological Rhythm Research, 35:3, 213-227 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09291010412331335760 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub- licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. -

Genomic and Gene Regulatory Signatures of Cryptozoic Adaptation

Wayne State University Wayne State University Associated BioMed Central Scholarship 2007 Genomic and gene regulatory signatures of cryptozoic adaptation: Loss of blue sensitive photoreceptors through expansion of long wavelength-opsin expression in the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum Magdalena Jackowska Wayne State University, [email protected] Riyue Bao Wayne State University, [email protected] Zhenyi Liu Washington University in St Louis School of Medicine, [email protected] Elizabeth C. McDonald Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, [email protected] Tiffany A. Cook Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, [email protected] Recommended Citation Jackowska et al. Frontiers in Zoology 2007, 4:24 doi:10.1186/1742-9994-4-24 Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/biomedcentral/153 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Associated BioMed Central Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. See next page for additional authors Authors Magdalena Jackowska, Riyue Bao, Zhenyi Liu, Elizabeth C. McDonald, Tiffany A. Cook, and Markus Friedrich This article is available at DigitalCommons@WayneState: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/biomedcentral/153 Frontiers in Zoology BioMed Central Research Open Access Genomic and gene regulatory signatures of cryptozoic adaptation: Loss of blue sensitive photoreceptors through expansion of long wavelength-opsin expression in the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum Magdalena Jackowska1, Riyue Bao1, Zhenyi Liu2, Elizabeth C McDonald3, Tiffany A Cook3 and Markus Friedrich*1,4 Address: 1Department of Biological Sciences, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI 48202 USA, 2Department of Molecular Biology and Pharmacology, Washington University in St Louis School of Medicine, 3600 Cancer Research Building, St. -

Ecology of the Marten in Glacier National Park

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1955 Ecology of the marten in Glacier National Park Vernon Duane Hawley The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hawley, Vernon Duane, "Ecology of the marten in Glacier National Park" (1955). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 6451. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/6451 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ECOLOGY OF THE MARTEN IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK by VERNON D. HAWLEY B# S# Montana State Iftiiversity, 1953 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Wildlife Technology MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1955 Approved by; yOhainman. Board af E%ü&niners y pean, Gradüate School ./ / f T j T Date UMI Number: EP37252 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Oiasartadikm FNjUishing UMI EP37252 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

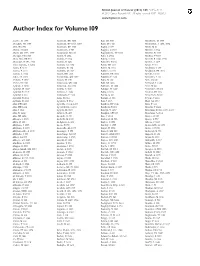

Author Index for Volume 109

British Journal of Cancer (2013) 109, 3133 – 3144 & 2013 Cancer Research UK All rights reserved 0007 – 0920/13 www.bjcancer.com Author Index for Volume 109 Aaseb, U 1467 Andersen, KK 3005 Bae, JM 1004 Benchetrit, M 1579 Abdallah, SO 1657 Andersen, RF 1243, 3067 Baek, JY 1420 Bendifallah, S 1498, 2774 Abel, GA 780 Anderson, KE 1908 Bagby, S 667 Benet, M 83 Abend, M 2286 Andersson, S 704 Baggott, C 2515 Benı´tez, J 2724 Abnet, CC 1367, 1997 Andonegui, MA 68 Bagnyukova, TV 1063 Bennett, K 1513 Aboagye, EO 2356 Andre, N 2024 Bahl, A 2554 Beohou, E 3057 Abou-Alfa, GK 915 Andre´s, E 2724 Bailey, S 2051 Berardi, R 1040, 1755 Absenger, G 395, 2316 Andre´s, R 1451 Baiocchi, G 184 Bercier, S 1437 Acha-Sagredo, A 2404 Andrew, AS 1954 Baird, DD 1291 Berge, Y 909 Adam, R 3126 Andrulis, IL 154 Baiter, M 2833 Bergkvist, L 257 Adams, E 2021 Andrulis, M 2665 Bakker, S 1093 Bergsland, EK 1725 Adenis, A 2574 Angell, HK 1618 Baldwin, DR 2058 Berndt, S 1352 Adjei, AA 1085 Annunziata, CM 1072 Baldwin, P 2533 Bernstein, L 761 Afchain, P 3057 Ansari, M 1271 Balic, M 589 Bert, AG 641 Afshar, M 1543 Antonescu, CR 2340 Ball, GR 1886 Bertrand, L 1586 Agaimy, A 2833 Antoniou, AC 1296 Ballester, M 1498 Betti, M 462 Agarwal, JP 2087 Anttila, A 2941 Balsdon, H 1549 Bettstetter, M 370 Agarwal, R 2515 Antunes, L 2646 Balta, S 3125 Beumer, JH 1725 Agarwal, S 872 Antunovic, P 2523 Bamia, C 332 Beuselinck, B 332 Agrawal, N 2051 Aoki, N 2155 Bamias, A 332 Beyene, J 2515 Agulnik, JS 2066 Aparicio, T 3057 Ban, J 2696 Bhat, GA 1367 Ahn, DH 1476 Apicella, C 154, 1296 Bandera, -

By Linda Stanek Illustrated by Shennen Bersani from the Award-Winning Team That Brought You Once Upon an Elephant, CBC Children’S Choice Book Aw a R D 2017

by Linda Stanek illustrated by Shennen Bersani From the award-winning team that brought you Once Upon an Elephant, CBC Children’s Choice Book Aw a r d 2017. What creeps while you sleep? Short, lyrical text makes this a perfect naptime or bedtime story. Young readers are introduced to nocturnal animals and their behaviors. Older readers learn more about each animal through As an early and middle childhood educator, Linda sidebar information. Stanek wants to inspire young learners, including children with written language disabilities, to write about things that excite them. Her own passion for teaching children about the importance of each link in the natural world provided the inspiration by Linda Stanek for Night Creepers. Linda has also written Once Upon an Elephant, The Pig and Miss Prudence and Beco’s Big Year: A Baby Elephant Turns One. illustrated by Shennen Bersani Linda has two grown sons and lives in Ohio with her husband and feline family members. Visit her website at www.lindastanek.com. Shennen Bersani is an award-winning illustrator with 2 million copies of her books cherished and read by children, parents, and teachers throughout the world. Her art delivers heartfelt emotion, the wonders of nature and science, Arbordale Publishing offers so much more and creates a unique joy for learning. Some of than a picture book. We open the door for Shennen’s other illustrated works include Honey children to explore the facts behind a story Girl; A Case of Sense; Once Upon an Elephant; they love. Animal Partners; Sea Slime: It’s Eeuwy, Gooey and Under the Sea; Shark Baby; Home in the Thanks to Kenneth Rainer, Education Cave; Astro: The Steller Sea Lion; The Glaciers Coordinator at the GTM Research Reserve, are Melting!, The Shape Family Babies; and and Cathleen McConnell, Community and Salamander Season for Arbordale.