Note to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15962-4 — The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature This fully revised second edition of The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature offers a comprehensive introduction to major writers, genres, and topics. For this edition several chapters have been completely re-written to relect major developments in Canadian literature since 2004. Surveys of ic- tion, drama, and poetry are complemented by chapters on Aboriginal writ- ing, autobiography, literary criticism, writing by women, and the emergence of urban writing. Areas of research that have expanded since the irst edition include environmental concerns and questions of sexuality which are freshly explored across several different chapters. A substantial chapter on franco- phone writing is included. Authors such as Margaret Atwood, noted for her experiments in multiple literary genres, are given full consideration, as is the work of authors who have achieved major recognition, such as Alice Munro, recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature. Eva-Marie Kröller edited the Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature (irst edn., 2004) and, with Coral Ann Howells, the Cambridge History of Canadian Literature (2009). She has published widely on travel writing and cultural semiotics, and won a Killam Research Prize as well as the Distin- guished Editor Award of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals for her work as editor of the journal Canadian -

Writing Here1

WRITING HERE1 W.H. NEW n 2003, for the BC Federation of Writers, Susan Musgrave assembled a collection of new fiction and poetry from some fifty-two IBC writers, called The FED Anthology.2 Included in this anthology is a story by Carol Matthews called “Living in ascii,” which begins with a woman recording her husband’s annoyance at whatever he sees as stupidity (noisy traffic and inaccurate grammar, for instance, and the loss of his own words when his computer apparently swallows them). This woman then tells of going to a party, of the shifting (and sometimes divisive) relationships among all the women who were attending, and of the subjects they discussed. These included a rape trial, national survival, men, cliffs, courage, cormorant nests, and endangered species. After reflecting on the etymology of the word “egg” (and its connection with the word “edge”), she then declares her impatience with schisms and losses, and her wish to recover something whole. The story closes this way: “If I were to tell the true story, I would write it not in words but in symbols, [like an] ... ascii printout. It would be very short and very true. It would go like this: moon, woman, woman; man, bird, sun; heart, heart, heart, heart, heart; rock, scissors, paper. The title would be egg. That would be the whole story.”3 This egg is the prologue to my comments here. So is the list of disparate nouns – or only seemingly disparate, in that (by collecting them as she does) the narrator connects them into story. -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Spring 2017 Department of English and Theatre Acadia University

VOLUME 24 SPRING 2017 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND THEATRE ACADIA UNIVERSITY Acadia English & Theatre Spring 2017 1 THEATRE REVIEWS dominated areas of the property, while the women, Mrs. Hale (Andrea VOICE Switzer) and Mrs. Peters (Jenna THREE SHORT PLAYS BY Newcomb), search the domestic to SUSAN GLASPELL uncover the truth. The interplay be- 4 (Directed by Anna Migliarisi) tween the men and women of this THEATRE REVIEWS Three Short Plays by Susan Glaspell by Emily MacLeod play is purposefully ironic, in that the Anton in Show Business women make numerous discoveries Minifest 2017 Acadia Theatre Company’s while being belittled by the men for production of three Glaspell plays, paying so much attention to the do- Trifles, Suppressed Desires, and mestic sphere. The detective jokes ATLANTIC UNDERGRADUATE Women’s Honor took place in about the domestics while coming up ENGLISH CONFERENCE November at Lower Denton Theatre. short in the investigation to secure These three plays were written by Minnie’s motive. There are a couple playwright Susan Glaspell in the of key pointed feminist moments that AUTHORS @ ACADIA early 1900s. In Acadia Theatre are not lost on the audience. The play Lee Maracle Armand Ruffo Camilla Gibb Elizabeth Hay Heather O’Neill Lisa Moore André Alexis Eden Robinson Meags Fitzgerald ENGLISH SOCIETY EVENTS Halloween Party Fundraising Bad Poetry Night STAFF Sarah Bishop Laurence Gumbridge Trifles: Andrea Switzer, Marcus Wong, Zachery Craig, & Jenna Newcomb Stuart Harris Nicole Havers Company’s production of these achieves a slow, but powerful, simple Sarah MacDonald plays, director Anna Migliarisi push- moment of feminist subversion when Emily MacLeod es the boundaries in terms of the the two women, Mrs. -

Governor General's Literary Awards

Bibliothèque interculturelle 6767, chemin de la Côte-des-neiges 514.868.4720 Governor General's Literary Awards Fiction Year Winner Finalists Title Editor 2009 Kate Pullinger The Mistress of Nothing McArthur & Company Michael Crummey Galore Doubleday Canada Annabel Lyon The Golden Mean Random House Canada Alice Munro Too Much Happiness McClelland & Steward Deborah Willis Vanishing and Other Stories Penguin Group (Canada) 2008 Nino Ricci The Origins of Species Doubleday Canada Rivka Galchen Atmospheric Disturbances HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. Rawi Hage Cockroach House of Anansi Press David Adams Richards The Lost Highway Doubleday Canada Fred Stenson The Great Karoo Doubleday Canada 2007 Michael Ondaatje Divisadero McClelland & Stewart David Chariandy Soucoupant Arsenal Pulp Press Barbara Gowdy Helpless HarperCollins Publishers Heather O'Neill Lullabies for Little Criminals Harper Perennial M. G. Vassanji The Assassin's Song Doubleday Canada 2006 Peter Behrens The Law of Dreams House of Anansi Press Trevor Cole The Fearsome Particles McClelland & Stewart Bill Gaston Gargoyles House of Anansi Press Paul Glennon The Dodecahedron, or A Frame for Frames The Porcupine's Quill Rawi Hage De Niro's Game House of Anansi Press 2005 David Gilmour A Perfect Night to Go to China Thomas Allen Publishers Joseph Boyden Three Day Road Viking Canada Golda Fried Nellcott Is My Darling Coach House Books Charlotte Gill Ladykiller Thomas Allen Publishers Kathy Page Alphabet McArthur & Company GovernorGeneralAward.xls Fiction Bibliothèque interculturelle 6767, -

Westwood Creative Artists ______

Westwood Creative Artists ___________________________________________ FRANKFURT CATALOGUE Fall 2018 INTERNATIONAL RIGHTS Director: Carolyn Forde Associate: Meg Wheeler AGENTS Carolyn Forde Jackie Kaiser Michael A. Levine Hilary McMahon John Pearce Bruce Westwood FILM & TELEVISION Michael A. Levine 386 Huron Street, Toronto, Ontario M5S 2G6 Canada Phone: (416) 964-3302 ext. 223 & 233 E-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] Website: www.wcaltd.com Table of Contents News from Westwood Creative Artists page 3 – 5 Recent sales page 6 – 7 Fiction Nicole Lundrigan, Hideaway page 10 Raziel Reid, Kens page 11 Alisa Smith, Doublespeak page 12 M.G. Vassanji, A Delhi Obsession page 13 Non-Fiction Sarah Berman, Don’t Call It a Cult page 16 Erin Davis, Mourning Has Broken page 17 Gail Gallant, The Changeling page 18 Don Gillmor, To The River page 19 Stephen J. Harper, Right Here, Right Now page 20 Thomas Homer-Dixon, Commanding Hope page 21 Darren McLeod, Mamaskatch page 22 Tessa McWatt, Shame on Me page 23 Ailsa Ross, The Woman Who Rode a Shark page 24 Poetry Najwa Zebian, The Nectar of Pain page 26 Titles of Special Note Karma Brown, Recipe for a Perfect Wife page 28 Kim Fu, The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore page 29 Thomas King, The Dreadfulwater series page 30 – 31 Manjushree Thapa, All of Us In Our Own Lives page 32 Richard Wagamese, Starlight page 33 Mark Abley, Watch Your Tongue page 34 Darrell Bricker & John Ibbitson, Empty Planet page 35 David Chariandy, I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You page 36 Rae Congdon, GAYBCs page 37 B. -

Department of English and American Studies the Canadian Short Story

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Bc. Katarína Kőrösiová The Canadian Short Story Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mrg. Kateřina Prajznerová, Ph. D. 2012 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to thank to my supervisor Mgr. Kateřina Prajznerová, Ph. D. for initiating me into this interesting subject, and mainly, for her help and valuable advice. I am also thankful for all the support I received from my family. Table of Contents 1. Introduction: What Makes the Canadian Short Story Canadian? 5 1.1. The Genre of the Short Story 7 1.2. The Canadian Short Story 15 2. Multiculturalism 25 2.1. Generational Differences 26 2.2. Biculturalism 32 2.3. Language and Naming 36 2.4. Minority or General Experience 38 3. Family and Gender 42 3.1. The Notion of Family and Home in Madeleine Thien‟s Stories 43 3.2. The Portrayal of Children 46 3.3. Alice Munro‟s Girls and Women 50 4. Place 57 4.1. Canada as Utopia 57 4.2. The Country and the City 63 5. Conclusion: The Relationship Between Form and Theme 68 Works Cited 74 Resumé (English) 78 Resumé (České) 79 1. Introduction: What Makes the Canadian Short Story Canadian? How do readers know that they are reading a Canadian short story? Lynch and Robbeson suggest an apparently easy and “common sense” solution for the problem: “we know [that] we‟re reading Canadian stories [when] the author is Canadian or / and the setting is Canadian” (2). -

Robinson, Eden (Subject) • Textual Record (Documentary Form) • Photographic Material (Documentary Form) • Arts and Culture (Subject) • First Nations (Subject)

Simon Fraser University Special Collections and Rare Books Finding Aid - Eden Robinson fonds (MsC 104) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.1 Printed: July 02, 2019 Language of description: English Rules for Archival Description Simon Fraser University Special Collections and Rare Books W.A.C. Bennett Library - Room 7100 Simon Fraser University 8888 University Drive Burnaby BC Canada V5A 1S6 Telephone: 778.782.8842 Email: [email protected] http://atom.archives.sfu.ca/index.php/msc-104 Eden Robinson fonds Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Series descriptions .......................................................................................................................................... -

Sexualized Bodies in Canadian Women's Short Fiction

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Saskatchewan's Research Archive Sexualized Bodies in Canadian Women’s Short Fiction A Dissertation Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada By AMELIA HORSBURGH 2016 © Copyright Amelia Horsburgh, 2016. All Rights Reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this dissertation in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of English University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 Canada OR Dean College of Graduate Studies and Research University of Saskatchewan 107 Administration Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A2 Canada i Abstract In this dissertation, I examine short stories by Canadian women writers from the 1970s to the 2000s to answer three overarching questions. -

Westwood 140764

Westwood Creative Artists ___________________________________________ LONDON CATALOGUE Spring 2020 INTERNATIONAL RIGHTS Director: Meg Wheeler AGENTS Chris Casuccio Jackie Kaiser Michael A. Levine Hilary McMahon John Pearce Bruce Westwood Meg Wheeler FILM & TELEVISION Michael A. Levine 386 Huron Street, Toronto, Ontario M5S 2G6 Canada Phone: (416) 964-3302 ext. 233 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.wcaltd.com Table of Contents News from Westwood Creative Artists page 2 – 4 Recent sales page 5 – 6 Fiction Caroline Adderson, A Russian Sister page 9 Glenn Dixon, Bootleg Stardust page 10 Zsuzsi Gartner, The Beguiling page 11 Frances Itani, The Company We Keep page 12 Thomas King, Indians on Vacation page 13 Annabel Lyon, Consent page 14 Damhnait Monaghan, New Girl in Little Cove page 15 Non-fiction Stephen Bown, The Company page 17 Allan Levine, Details Are Unprintable page 18 Keith Maillard, Fatherless page 19 Rahaf Mohammed, Rebel page 20 Michael Posner, Leonard Cohen page 21 Titles of Special Note Keith Ross Leckie, Cursed! page 23 Kathryn Nicolai, Nothing Much Happens page 24 Sara O’Leary, The Ghost in the House page 25 Madhur Anand, This Red Line Goes Straight to Your Heart page 26 Tara Henley, Lean Out page 27 Thomas Homer-Dixon, Commanding Hope page 28 Bruce Kirkby, Blue Sky Kingdom page 29 Liz Levine, Nobody Ever Talks About Anything But the End page 30 Selected client list page 31 Co-agents page 32 March 2020 Welcome to Westwood Creative Artists’ Spring 2020 catalogue! We’re looking forward to another year of bringing exceptional writers and their works to an international audience. -

August 15-18

8:00 pm • Thursday • August 15 1:00 pm • Friday • August 16 7:00 pm • Friday • August 16 Welcome to the 37th 1 Richard Van Camp 4 Ian Williams 7 Elizabeth Hay Sunshine Coast Festival A member of the Dogrib (Tlicho) Nation from Fort Smith, Ian Williams is one of those special writers excelling at penning “The way I live is to write,” Elizabeth Hay told CBC’s Shelagh of the Written Arts. NWT, Richard Van Camp’s compelling stories take many forms. poetry as well as prose. His first book, You Know Who You Are, Rogers in an interview. With 10 published books and a host of We acknowledge with gratitude that the Festival takes place He has written eight books for children and babies, including was a finalist for the ReLit Poetry Prize, while Personals was literary honours, it’s safe to say Hay is living a good writing life. on the traditional unceded territory of the shíshálh Nation. Little You, which won the R. Ross Arnett Award for Children’s shortlisted for the Griffin Poetry Prize and the Robert Kroetsch Her first novel, A Student of the Weather, won the Canadian Literature; authored two comic books and four graphic novels, Award. His short story collection, Not Anyone’s Anything, won Authors Association Award for Fiction; her second, Garbo Tickets will go on sale on including A Blanket of Butterflies which was nominated for an the Danuta Gleed Literary Award for the best first collection of Laughs, won the Ottawa Book Award; and her third, Late Wednesday, May 29 at 8 am Eisner Award; scripted for the Gemini-winning CBC television short fiction in Canada. -

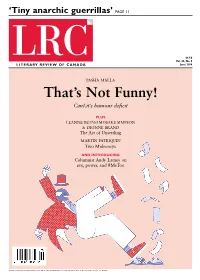

That's Not Funny!

‘Tiny anarchic guerrillas’ PAGE 11 $6.50 Vol. 26, No. 5 June 2018 PASHA MALLA That’s Not Funny! CanLit’s humour deficit PLUS LEANNE BETASAMOSAKE SIMPSON & DIONNE BRAND The Art of Unsettling MARTIN PATRIQUIN Two Mulroneys AND INTRODUCING Columnist Andy Lamey on sex, power, and #MeToo Publications Mail Agreement #40032362. Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to LRC, Circulation Dept. PO Box 8, Station K, Toronto, ON M4P 2G1 Literary Review of Canada 100 King Street West, Suite 2575 P.O. Box 35 Station 1st Canadian Place Toronto ON M5X 1A9 email: [email protected] reviewcanada.ca Vol. 26, No. 5 • June 2018 T: 416-861-8227 Charitable number: 848431490RR0001 To donate, visit reviewcanada.ca/support EDITOR IN CHIEF 3 A Little Sincerity 20 Delirious in the Pink House Sarmishta Subramanian Letter from the editor A poem [email protected] Sarmishta Subramanian John Wall Barger ASSISTANT EDITOR Bardia Sinaee 4 The Art of Unsettling 21 Sisterhood of the Secret Pantaloons ASSOCIATE EDITOR Leanne Betasamosake Simpson in Suffragists and their descendants Beth Haddon conversation with Dionne Brand One Hundred Years of Struggle by Joan Sangster POETRY EDITOR and Just Watch Us by Christabelle Sethna and Moira MacDougall 6 Ecclesiasticus XXII Steve Hewitt COPY EDITOR A poem Susan Whitney Patricia Treble George Elliott Clarke CONTRIBUTING EDITORS 23 The Americanization of Oscar Mohamed Huque, Andy Lamey, Molly 8 The Other Side of ‘Irish Eyes’ The early days of a modern celebrity Peacock, Robin Roger, Judy Stoffman Brian Mulroney abroad and at