The Army School of Music 1922 - 1940

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of Fall 8-21-2012 Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the Music Commons Lefferts, Peter M., "Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I" (2012). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 25. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1 Version of 08/21/2012 This essay is a work in progress. It was uploaded for the first time in August 2012, and the present document is the first version. The author welcomes comments, additions, and corrections ([email protected]). Black US Army bands and their bandmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts This essay sketches the story of the bands and bandmasters of the twenty seven new black army regiments which served in the U.S. Army in World War I. They underwent rapid mobilization and demobilization over 1917-1919, and were for the most part unconnected by personnel or traditions to the long-established bands of the four black regular U.S. Army regiments that preceded them and continued to serve after them. Pressed to find sufficient numbers of willing and able black band leaders, the army turned to schools and the entertainment industry for the necessary talent. -

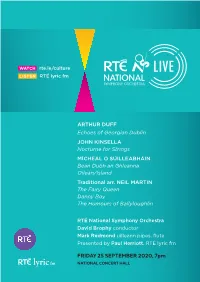

RTE NSO 25 Sept Prog.Qxp:Layout 1

WATCH rte.ie/culture LISTEN RTÉ lyric fm ARTHUR DUFF Echoes of Georgian Dublin JOHN KINSELLA Nocturne for Strings MÍCHEÁL Ó SÚILLEABHÁIN Bean Dubh an Ghleanna Oileán/Island Traditional arr. NEIL MARTIN The Fairy Queen Danny Boy The Humours of Ballyloughlin RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra David Brophy conductor Mark Redmond uilleann pipes, flute Presented by Paul Herriott, RTÉ lyric fm FRIDAY 25 SEPTEMBER 2020, 7pm NATIONAL CONCERT HALL 1 Arthur Duff 1899-1956 Echoes of Georgian Dublin i. In College Green ii. Song for Amanda iii. Minuet iv. Largo (The tender lover) v. Rigaudon Arthur Duff showed early promise as a musician. He was a chorister at Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral and studied at the Royal Irish Academy of Music, taking his degree in music at Trinity College, Dublin. He was later awarded a doctorate in music in 1942. Duff had initially intended to enter the Church of Ireland as a priest, but abandoned his studies in favour of a career in music, studying composition for a time with Hamilton Harty. He was organist and choirmaster at Christ Church, Bray, for a short time before becoming a bandmaster in the Army School of Music and conductor of the Army No. 2 band based in Cork. He left the army in 1931, at the same time that his short-lived marriage broke down, and became Music Director at the Abbey Theatre, writing music for plays such as W.B. Yeats’s The King of the Great Clock Tower and Resurrection, and Denis Johnston’s A Bride for the Unicorn. The Abbey connection also led to the composition of one of Duff’s characteristic works, the Drinking Horn Suite (1953 but drawing on music he had composed twenty years earlier as a ballet score). -

Irish All-Army Champions 1923-1995

Irish All-Army Champions 1923-1995 To be forgotten is to die twice Most Prolific All Army Individual Titles Name Command Disciplines Number of individual titles Capt Gerry Delaney Curragh Command Sprints 30 Pte Jim Moran Ordnance Service Jumps, Hurdles 25 Capt Mick O' Farrell Curragh Command Throws, Jumps, Hurdles 19 Capt Billy McGrath Curragh Command Throws 17 Comdt Bernie O' Callaghan Eastern Command Walks 17 Cpl Brendan Downey Curragh Command Middle Distance, C/C 17 C/S Frank O' Shea Curragh Command Throws 16 Comdt Kevin Humphries Air Corps Middle Distance,C/C 16 Pte Tommy Nolan Curragh Command Jumps, Hurdles 15 Comdt JJ Hogan Curragh Command Throws 14 Capt Tom Ryan Eastern Command Hurdles, Pole Vault 14 Cpl J O'Driscoll Curragh Command Weight Throw 14 C/S Tom Perch Southern Command Throws 13 Pte Sean Carlin Western Command FCA Jumps, Throws 13 Capt Junior Cummins Southern Command Middle Distance 13 Capt Dave Ashe Curragh Command Jumps, Sprints 13 CQMS Willy Hyland Southern Command Hammer 12 Capt Jimmy Collins Ordnance Service 440,880, 440 Hurdles 11 Capt Gerry N Coughlan Western Command 220,440,880, Mile 11 Capt Pat Healy Curragh Command pole Vault, Throws 11 Sgt Paddy Murphy Curragh Command 5,000m, C/C 11 CQMS Billy Hyland Southern Command Hammer 11 Sgt J O'Driscoll Curragh Command 56 Lb W.F 14 Notable Athletes who won Irish All Army Championshiups Name / Command About 1st All Army title Capt Gerry N Coughlan, Western Command Olympian 1924 Tpr Noel Carroll, Eastern Command Double Olympian 1959 Pte Danny McDaid, Eastern Command FCA -

Nachhall Entspricht Mit Ausdeutungen Wie: Nachwirkend, Nachhaltig, Nicht Gleich Verklingend Dem Anliegen Des Buches Und Der Reihe Komponistinnen Und Ihr Werk

Christel Nies Der fünfte Band der Reihe Komponistinnen und ihr Werk doku- mentiert für die Jahre 2011 bis 2016 einundzwanzig Konzerte und Veranstaltungen mit Werkbeschreibungen, reichem Bildmaterial und den Biografien von 38 Komponistinnen. Sieben Komponistinnen beantworten Fragen zum Thema Komponistinnen und ihre Werke heute. Olga Neuwirth gibt in einem Interview mit Stefan Drees Auskunft über ihre Er- fahrungen als Komponistin im heutigen Musikleben. Freia Hoffmann (Sofie Drinker Institut), Susanne Rode- Breymann Christel Nies (FMG Hochschule für Musik, Theater und Medien, Han- nover) und Frank Kämpfer (Deutschlandfunk) spiegeln in ihren Beiträgen ein Symposium mit dem Titel Chancengleich- heit für Komponistinnen, Annäherung auf unterschiedlichen Wegen, das im Juli 2015 in Kassel stattfand. Christel Nies berichtet unter dem Titel Komponistinnen und ihr Werk, eine unendliche Geschichte von Entdeckungen und Aufführungen über ihre ersten Begegnungen mit dem Thema Frau und Musik, den darauf folgenden Aktivitäten und über Erfolge und Erfahrungen in 25 Jahren dieser „anderen Konzertreihe“. Der Buchtitel Nachhall entspricht mit Ausdeutungen wie: nachwirkend, nachhaltig, nicht gleich verklingend dem Anliegen des Buches und der Reihe Komponistinnen und ihr Werk. Nachhall Komponistinnen und ihr Werk V ISBN 978-3-7376-0238-9 ISBN 978-3-7376-0238-9 Komponistinnen und ihr Werk V 9 783737 602389 Christel Nies Nachhall Komponistinnen und ihr Werk V 1 2 Christel Nies Nachhall Komponistinnen und ihr Werk V kassel university kassel university press · Kassel press 3 Komponistinnen und ihr Werk V Eine Dokumentation der Veranstaltungsreihe 2011 bis 2016 Gefördert vom Hessischen Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kunst Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. -

Canadian Infantry Combat Training During the Second World War

SHARPENING THE SABRE: CANADIAN INFANTRY COMBAT TRAINING DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR By R. DANIEL PELLERIN BBA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2007 BA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2008 MA, University of Waterloo, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in History University of Ottawa Ottawa, Ontario, Canada © Raymond Daniel Ryan Pellerin, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii ABSTRACT “Sharpening the Sabre: Canadian Infantry Combat Training during the Second World War” Author: R. Daniel Pellerin Supervisor: Serge Marc Durflinger 2016 During the Second World War, training was the Canadian Army’s longest sustained activity. Aside from isolated engagements at Hong Kong and Dieppe, the Canadians did not fight in a protracted campaign until the invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The years that Canadian infantry units spent training in the United Kingdom were formative in the history of the Canadian Army. Despite what much of the historical literature has suggested, training succeeded in making the Canadian infantry capable of succeeding in battle against German forces. Canadian infantry training showed a definite progression towards professionalism and away from a pervasive prewar mentality that the infantry was a largely unskilled arm and that training infantrymen did not require special expertise. From 1939 to 1941, Canadian infantry training suffered from problems ranging from equipment shortages to poor senior leadership. In late 1941, the Canadians were introduced to a new method of training called “battle drill,” which broke tactical manoeuvres into simple movements, encouraged initiative among junior leaders, and greatly boosted the men’s morale. -

YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares Beside the Edmund Dulac Memorial Stone to W

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/194 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the same series YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 1, 2 Edited by Richard J. Finneran YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 3-8, 10-11, 13 Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS AND WOMEN: YEATS ANNUAL No. 9: A Special Number Edited by Deirdre Toomey THAT ACCUSING EYE: YEATS AND HIS IRISH READERS YEATS ANNUAL No. 12: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould and Edna Longley YEATS AND THE NINETIES YEATS ANNUAL No. 14: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS’S COLLABORATIONS YEATS ANNUAL No. 15: A Special Number Edited by Wayne K. Chapman and Warwick Gould POEMS AND CONTEXTS YEATS ANNUAL No. 16: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould INFLUENCE AND CONFLUENCE: YEATS ANNUAL No. 17: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares beside the Edmund Dulac memorial stone to W. B. Yeats. Roquebrune Cemetery, France, 1986. Private Collection. THE LIVING STREAM ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF A. NORMAN JEFFARES YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 A Special Issue Edited by Warwick Gould http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Gould, et al. (contributors retain copyright of their work). The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text. -

Alan Lomax: Selected Writings 1934-1997

ALAN LOMAX ALAN LOMAX SELECTED WRITINGS 1934–1997 Edited by Ronald D.Cohen With Introductory Essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew L.Kaye ROUTLEDGE NEW YORK • LONDON Published in 2003 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 www.routledge-ny.com Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE www.routledge.co.uk Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group. This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” All writings and photographs by Alan Lomax are copyright © 2003 by Alan Lomax estate. The material on “Sources and Permissions” on pp. 350–51 constitutes a continuation of this copyright page. All of the writings by Alan Lomax in this book are reprinted as they originally appeared, without emendation, except for small changes to regularize spelling. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lomax, Alan, 1915–2002 [Selections] Alan Lomax : selected writings, 1934–1997 /edited by Ronald D.Cohen; with introductory essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew Kaye. -

Austin Clarke Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 83 Austin Clarke Papers (MSS 38,651-38,708) (Accession no. 5615) Correspondence, drafts of poetry, plays and prose, broadcast scripts, notebooks, press cuttings and miscellanea related to Austin Clarke and Joseph Campbell Compiled by Dr Mary Shine Thompson 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 7 Abbreviations 7 The Papers 7 Austin Clarke 8 I Correspendence 11 I.i Letters to Clarke 12 I.i.1 Names beginning with “A” 12 I.i.1.A General 12 I.i.1.B Abbey Theatre 13 I.i.1.C AE (George Russell) 13 I.i.1.D Andrew Melrose, Publishers 13 I.i.1.E American Irish Foundation 13 I.i.1.F Arena (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.G Ariel (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.H Arts Council of Ireland 14 I.i.2 Names beginning with “B” 14 I.i.2.A General 14 I.i.2.B John Betjeman 15 I.i.2.C Gordon Bottomley 16 I.i.2.D British Broadcasting Corporation 17 I.i.2.E British Council 17 I.i.2.F Hubert and Peggy Butler 17 I.i.3 Names beginning with “C” 17 I.i.3.A General 17 I.i.3.B Cahill and Company 20 I.i.3.C Joseph Campbell 20 I.i.3.D David H. Charles, solicitor 20 I.i.3.E Richard Church 20 I.i.3.F Padraic Colum 21 I.i.3.G Maurice Craig 21 I.i.3.H Curtis Brown, publisher 21 I.i.4 Names beginning with “D” 21 I.i.4.A General 21 I.i.4.B Leslie Daiken 23 I.i.4.C Aodh De Blacam 24 I.i.4.D Decca Record Company 24 I.i.4.E Alan Denson 24 I.i.4.F Dolmen Press 24 I.i.5 Names beginning with “E” 25 I.i.6 Names beginning with “F” 26 I.i.6.A General 26 I.i.6.B Padraic Fallon 28 2 I.i.6.C Robert Farren 28 I.i.6.D Frank Hollings Rare Books 29 I.i.7 Names beginning with “G” 29 I.i.7.A General 29 I.i.7.B George Allen and Unwin 31 I.i.7.C Monk Gibbon 32 I.i.8 Names beginning with “H” 32 I.i.8.A General 32 I.i.8.B Seamus Heaney 35 I.i.8.C John Hewitt 35 I.i.8.D F.R. -

HR14401 Military Band Recordings” of the White House Records Office: Legislation Case Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 18, folder “1974/12/31 HR14401 Military Band Recordings” of the White House Records Office: Legislation Case Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Exact duplicates within this folder were not digitized. Digitized from Box 18 of the White House Records Office Legislation Case Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE ACTION WASHINGTON Last Day: December 31 December 27, 1974 MEMORANDUM FOR THE PRE~ENT FROM: KEN corV SU'BJECT: Enrolled Bill H.R. 14401 Military Band Recordings Attached for your consideration is H.R. 14401, sponsored by Representative Hebert, which would authorize the official military bands to make recordings and tapes for commercial sale commemorating the Bicentennial. OMB recommends approval and provides additional back ground information in its enrolled bill report (Tab A). Phil Areeda and Max Friedersdorf both recommend approval. RECOMMENDATION That you sign H.R. 14401 (Tab B). -

Download Booklet

1 In My Liverpool Home 5.18 9 The Gateway to the Atlantic 5.09 17 Danny Boy 2.57 Words and music: The Spinners Words: Roger McGough Words: Frederic Weatherly arr. Carmel Smickersgill Music: Richard Miller Music: Traditional ‘Londonderry Air’ arr. Stephen Hough 2 Amazing Grace 3.01 10 Liverpool Lullaby 7.04 Words: John Newton Words: Stan Kelly-Bootle 18 The Last Rose of Summer 3.57 Music: Anon. (1829) ‘New Britain’ arr. Bethan Morgan-Williams Words: Thomas Moore arr. Armand Rabot Music: Traditional ‘Aislean an Oigfear’ or 11 Johnny Todd 1.51 ‘The Young Man’s Dream’ arr. Benjamin Britten 3 My Native Land 1.27 Words and music: Traditional [Roud 1102] Words: Traditional arr. Armand Rabot 19 The Leaving of Liverpool 4.44 Music: Charles Ives Words and music: Traditional [Roud 9435] 12 What Will They Tell Me Tonight? 4.17 arr. Richard Miller 4 Homeward Bound 4.28 From the opera Pleasure Words and music: Traditional [Roud 927] Words: Melanie Challenger 20 All Our Different Voices 4.25 arr. Marco Galvani Music: Mark Simpson Words: Mandy Ross Music: Timothy Jackson 5 Song to the Seals 3.59 13 Madam and Her Madam 0.59 Words: Harold Boulton Words: Langston Hughes 21 You’ll Never Walk Alone 4.04 Music: Granville Bantock Music: Stephen Hough From the musical Carousel Words: Oscar Hammerstein 6 I Saw Three Ships 2.56 14 The World You’re Coming Into 2.17 Music: Richard Rodgers Words and music: Traditional carol [Roud 700] Words: Paul McCartney arr. Grace Evangeline Mason Music: Paul McCartney and Carl Davis 75.03 7 Sea Fever 2.20 15 Blackbird 2.45 Words: John Masefi eld Words and music: John Lennon and Paul McCartney Music: John Ireland arr. -

Artillery Club's Newsletter 2 of 2020 ( 05 Jun

The Artillery Club – 05 Jun 20 TAKE POST - THE ARTILLERY CLUB’s NEWSLETTER 2/2020 INTRODUCTION Since the publication of Newsletter 1/2020 on 27 February, the Covid-19 pandemic has completely curtailed the Artillery Club’s activities. Stay Safe, Stay Well and Stay Connected. Accordingly, the main purpose of this Newsletter is to inform the Club’s membership of the situation regarding the 2020 activities. Following an assessment of the evolving Covid-19 situation, prevailing Government advice, the Club’s responsibilities for its members including serving personnel, and in partnership with the appropriate actors involved in the Field Trips, without hesitation, on 12 March, the Club’s Committee decided to cancel the Field Trip to the Ordnance School and the National Stud, and the Field Trip to Fort Shannon, Foynes Flying Boat Museum, and deferred the events to 2021. Likewise, for the same reasons, on 22 May, the Club’s Committee deferred until 2021, the Decades’ Reunion and the Foreign Field Trip to London. Currently, the 2020 Golf Outing remains under review. The Committee apologies for any inconvenience caused to those members who intended to participate in the cancelled events. Hopefully, those who accrued travel and accommodation costs will be refunded by the providers. Once a Gunner – Always a Gunner The Artillery Club – 05 Jun 20 Details of this Operational Pause are contained in the Activities Section of this Newsletter. On 22 May, the modified Diary of Events for 2020 was posted on the Club’s website, and is attached as Annex A. In addition to the Activities Section, Newsletter 2/2020 includes: Promotion of a Gunner Officer to the General rank, Joint Task Force for Covid-19, Governance, Activity Update, News from the Artillery Corps, and Looking into the Past. -

October 2019 Boston’S Hometown VOL

October 2019 Boston’s hometown VOL. 30 # 10 journal of Irish culture. $2.00 Worldwide at All contents copyright © 2019 bostonirish.com Boston Neighborhood News, Inc. Boston Irish Honors celebrate four who honor their heritage The city’s top hotelier, a pioneering leader in educa- tion, and a couple who have led the transformation of Boston’s waterfront will be the honorees at next month’s tenth annual Boston Irish Honors, the season’s premier celebration of Irish-American achievement in Massachusetts. The luncheon, convened by the Boston Irish Reporter, will see hundreds of guests gathered at Seaport Boston Hotel on Fri., Oct. 18. James M. Carmody, the vice president and general manager of Seaport Hotel & Seaport World Trade Center, will be honored for his distinguished career in hospitality and for his leadership in philanthropy. Carmody, who is the current chair of the Greater Boston Convention and Visitors Bureau, serves on the board of Cathedral High School. Grace Cotter Regan is the first woman to lead Boston College High School and one of the nation’s most highly regarded leaders in Catholic education. She previously served as head of school at St. Mary’s High School in Introducing the Irish naval offshore Patrol Vessel L.É. SamuelBeckett #P61, which will be visiting Boston Lynn and as provincial assistant and executive director this month. Public visiting hours will be 10 a.m.to 5 p.m. at Charlestown Navy Yard on Fri., Oct. 4, and of advancement for the New England Province of Jesuits. Saturday, Oct 5. Plans are being made for a wreath-laying ceremony at the Deer Island Irish Memorial The daughter of the late legendary BC High football as the ship passes and leaves Boston Harbor on Oct 7.