ABDULRAHMAN ALHARBI, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

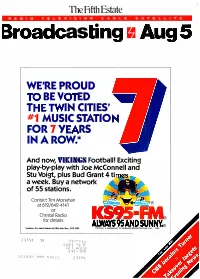

Broadcasting Ii Aug 5

The Fifth Estate R A D I O T E L E V I S I O N C A B L E S A T E L L I T E Broadcasting ii Aug 5 WE'RE PROUD TO BE VOTED THE TWIN CITIES' #1 MUSIC STATION FOR 7 YEARS IN A ROW.* And now, VIKINGS Football! Exciting play -by-play with Joe McConnell and Stu Voigt, plus Bud Grant 4 times a week. Buy a network of 55 stations. Contact Tim Monahan at 612/642 -4141 or Christal Radio for details AIWAYS 95 AND SUNNY.° 'Art:ron 1Y+ Metro Shares 6A/12M, Mon /Sun, 1979-1985 K57P-FM, A SUBSIDIARY OF HUBBARD BROADCASTING. INC. I984 SUhT OGlf ZZ T s S-lnd st-'/AON )IMM 49£21 Z IT 9.c_. I Have a Dream ... Dr. Martin Luther KingJr On January 15, 1986 Dr. King's birthday becomes a National Holiday KING... MONTGOMERY For more information contact: LEGACY OF A DREAM a Fox /Lorber Representative hour) MEMPHIS (Two Hours) (One-half TO Written produced and directed Produced by Ely Landau and Kaplan. First Richard Kaplan. Nominated for MFOXILORBER by Richrd at the Americ Film Festival. Narrated Academy Award. Introduced by by Jones. Harry Belafonte. JamcsEarl "Perhaps the most important film FOX /LORBER Associates, Inc. "This is a powerful film, a stirring documentary ever made" 432 Park Avenue South film. se who view it cannot Philadelphia Bulletin New York, N.Y. 10016 fail to be moved." Film News Telephone: (212) 686 -6777 Presented by The Dr.Martin Luther KingJr.Foundation in association with Richard Kaplan Productions. -

Chitwood Family

Early Family History and Background Chitwood Family (and related lines) Jean (Cragun) Tombaugh TOMBAUGH HOUSE 700 Pontiac Street Rochester, Indiana 46975 Early Family History and Background Copyright © 1965 Jean (Cragun) Tombaugh First Printing (by mimeograph) 1965 Wendell C. Tombaugh Second Printing (by offset press) 1976 Tombaugh Publishing House Third Printing (by copier) 1981 Tombaugh Publishing House Fourth Printing (by IBM computer) 1989 TOMBAUGH HOUSE Fifth Printing (by Macintosh computer) 1992 TOMBAUGH HOUSE Passages from Shakespeare of London by Marchette Chute, copyright, 1949, by E. P. Dutton & co., Inc., reprinted by permission of the publishers. Also see Acknowledgments. Early Family History and Background PREFACE The purpose of this book is to preserve family history and to perpetuate pride in the accomplishments of our pioneer ancestors. It is understandable that the contents of Chapter One may be tiresome reading to some. However, it was included for the benefit of those who might want to go more thoroughly into the background of the family. The old and original spellings - and misspellings - have been used. This book is not intended to be a final story of the Chitwood family of Virginia, but, rather, a first chapter of the story, which we hope will never be ended. It may appear strange that a native of Illinois, born of parents from Kansas, living in Indiana, writes a book about people in Virginia. True, much information is available, if at all, only in Virginia. But, the Indiana State Library, the Fort Wayne (Ind.) Public Library and the National Archives have vast amounts of pertinent information on their shelves, on microfilm and on microcards; and the courteous assistance of their personnel must be remembered. -

Campaign Addresses Illegal Downloads Employees Take Courses

the Observer The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s ndsmcobserver.com Volume 44 : Issue 117 THURSDAY, APRIL 7, 2011 ndsmcobserver.com Campaign addresses illegal downloads Professor By AMANDA GRAY researches News Writer A campaign to inform students education about illegal file sharing began recently, Robert Casarez, assis- tant director of the Office of By ANNA BOARINI Resident Life and Housing News Writer (ORLH), said Wednesday. The campaign, held in con- Peace studies Professor junction with the Office of Catherine Bolten, an anthro- Information Technology (OIT) pologist by trade, has focused and help from the Office of her research on the state of General Counsel (OGC), launched education in post-war soci- this week to educate students eties, specifically Sierra about the consequences of Leone. engaging in illegal file sharing, “I started out working as an Casarez said. apprentice for a medicine “We would like to take a proac- man studying ethnobotany in tive approach on the issue rather Botswana 15 years ago, than waiting for the violations,” Bolten said. “When I went to he said. “Over the last year, the LAUREN KALINOSKI | Observer Graphic Cambridge for my master’s I number of copyright infringe- wanted to study AIDS, but ment notices that the University is engaging in illegal download- expressed permission from the Copyright Act representative in after I made a very good has received has more than dou- ing or sharing of copyrighted copyright owner, Casarez said. the OGC, which is then forward- friend from Sierra Leone, bled, and we are aiming to keep material on the University’s net- File sharing is monitored on the ed on to our office for identifica- they convinced me I would be as many students out of the disci- work at any given time. -

How George Soros Sacked Glenn Beck | the Soros Files

12/19/2015 How George Soros Sacked Glenn Beck | The Soros Files ASI You Tube Conference Docs Conference Speeches Contact Us FREE NEWSLETTER Sitemap Who We Are How George Soros Sacked Glenn Beck by Cliff Kincaid on 19 Oct 2011 A recent interview of Fox News chief Roger Ailes by Howard Kurtz suggested that the channel is becoming less conservative by design. The real question, not addressed in the piece, is whether the relentless attacks on the channel by George Sorosfunded groups have anything to do with this change in the direction of the popular channel and the demise of the Glenn Beck program in particular. On Glenn Beck’s new TV program, carried on the Internet, Beck himself seemed to indicate this was the case. Talking about Orson Wells, his career, vision and his “Citizen Kane” movie, Beck said, “One of the biggest things [he taught me was] he picked a lot of illadvised fights, sometimes risking his entire career against titans of industry. It did occur to me recently maybe I should have considered that little part of his life a little more before I locked horns with George Soros.”1 The implication is that Beck’s battle with Soros left him without a job on Fox News. If this is the case, then we have reached a point in the United States when a private individual has obtained the power to prevent the most popular cable news channel in the country from subjecting his financial and political influence to scrutiny. It is important to see how this was done. -

Crime in the News

LESSON PLAN Level: Grades 10 to 12 About the Author: MediaSmarts Crime in the News Overview In this lesson students explore the commercial and ethical issues surrounding the reporting of crime in televised newscasts. They begin by discussing their attitudes toward crime, followed by the reading of a handout comparing Canadian and American crime reporting and further discussion about crime and 'the business' of television news. Students further explore how the media affect our perceptions about crime through a discussion on the media's treatment of various 'crime waves.' This lesson includes a group activity where students audit nightly newscasts based on guidelines they have established for responsible TV crime reporting. Learning Outcomes Students will: understand that the news is a form of entertainment which, like other television programs, competes for viewers appreciate the different needs of local and national news stations, and how this affects the selection of news items appreciate the challenges faced by journalists in trying to offer crime reporting that is not sensational. understand the role of crime reporting in attracting viewers understand the ways in which crime reporting affects our own perceptions of crime. Preparation and Materials A good introduction to the predominance of crime in local newscasts is the film If It Bleeds It Leads (which can be ordered online through Amazon.com). Photocopy: Our Top Story Tonight Should the Coverage Fit the Crime? Should the Coverage Fit the Crime? Questions Crime Audit For extension activity, photocopy WSVN in Miami: Diary of the American Nightmare. www.mediasmarts.ca 1 © 2012 MediaSmarts Crime in the News ● Lesson Plan ● Grades 10 – 12 Procedure Guided Discussion Ask students: On average, do you think crime is increasing or decreasing in Canada? (Tally and record the number of students who answer 'yes' to this question, and the number who answer 'no'.) Distribute Our Top Story Tonight to students. -

The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know And

T H E ELEMENTS OF JOURNALISM ALSO BY THESE AUTHORS Warp Speed: America in the Age of Mixed Media Copyright © 2001 by Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Published by Crown Publishers, New York, New York. Member of the Crown Publishing Group. Random House, Inc. New York, Toronto, London, Sydney, Auckland www.randomhouse.com CROWN is a trademark and the Crown colophon is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc. Design by Barbara Sturman Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kovach, Bill. The elements of journalism : what newspeople should know and the public should expect / Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel. 1. Journalistic ethics. 2. Journalism—United States. I. Rosenstiel, Tom. II. Title. PN4756.K67 2001 174’.9097—dc21 00-047450 eISBN 0-609-50431-2 v1.0 For Lynne & For Beth and Karina CONTENTS Introduction 1 What Is Journalism For? 2 Truth: The First and Most Confusing Principle 3 Who Journalists Work For 4 Journalism of Verification 5 Independence from Faction 6 Monitor Power and Offer Voice to the Voiceless 7 Journalism as a Public Forum 8 Engagement and Relevance 9 Make the News Comprehensive and Proportional 10 Journalists Have a Responsibility to Conscience ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INDEX INTRODUCTION As anthropologists began comparing notes on the world’s few remaining primitive cultures, they discovered something unexpected. From the most isolated tribal societies in Africa to the most distant islands in the Pacific, people shared essentially the same definition of what is news. -

DISH Fires up Its News and Political Programming with Glenn Beck's Theblaze

September 12, 2012 DISH Fires Up Its News and Political Programming With Glenn Beck's TheBlaze NEW YORK, NY and ENGLEWOOD, CO -- (Marketwire) -- 09/12/12 -- ● Beck's 24-hour News, Information and Entertainment Network Extends To Television Starting with DISH on Sept. 12 at 5 p.m. EDT on channel 212 ● TheBlaze Continues its Rapid Growth -- Original Content Grew the Network into One of the World's Most Subscribed-to Online Streaming Networks in Just One Year ● Network has Attracted Some of the Best Up-and-coming Talent in News and Opinion Programming with Will Cain, SE Cupp, Lu Hanessian, Amy Holmes, Raj Nair, Brian Sack, Buck Sexton and Andrew Wilkow TheBlaze Inc. and DISH Network, LLC announced today that TheBlaze, Glenn Beck's online 24-hour news, information and entertainment network will now be available on television starting, at launch, exclusively on DISH. TheBlaze joins DISH's selection of news and commentary programming representing all points on the political spectrum, including MSNBC, BBC America, CNN, Current, Comedy Central and FOX News. The online network launched a year ago today as GBTV and quickly grew into one of the world's largest online streaming networks. TheBlaze will be available to DISH viewers on channel 212 as part of DISH's America's Top 250 package or a la carte for $5 a month. The channel launches today at 5 p.m. EDT and customers can order a la carte starting tomorrow. TheBlaze will be available as a free preview for all DISH customers through Sept. 26. TheBlaze will continue to be available direct to consumers through its online subscription platform as TheBlaze TV on TheBlaze.com and various Internet-connected devices. -

Glenn Beckâ•Žs Attacks on Frances Fox Piven Trigger Death Threats

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Occidental College Scholar Occidental College OxyScholar UEP Faculty & UEPI Staff choS larship Urban and Environmental Policy 1-23-2011 Glenn Beck’s Attacks on Frances Fox Piven Trigger Death Threats Peter Dreier Occidental College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.oxy.edu/uep_faculty Part of the American Politics Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Community-based Learning Commons, Community-based Research Commons, Comparative Politics Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Health Policy Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Other Political Science Commons, Other Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Public Policy Commons, Social Policy Commons, Transportation Commons, Urban Studies Commons, Urban Studies and Planning Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons Recommended Citation Dreier, P. (2011, January 23). Glenn Beck's Attacks on Frances Fox Piven Trigger Death Threats. Breaking News and Opinion on The Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/peter-dreier/glenn-becks-attacks-on-fr_b_812690.html This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Urban and Environmental Policy at OxyScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in UEP Faculty & UEPI Staff choS larship by an authorized administrator of OxyScholar. For more information, please contact -

EXPANDING OUR NATIONAL REACH Review of 2010: a Letter from Our President & CEO

2010 ANNUAL REPORT EXPANDING OUR NATIONAL REACH Review of 2010: A Letter from Our President & CEO ...............................................................3 Launching Innovative New Ways to Fight Cruelty ......................................................................5 Bringing the Perpetrators of Cruelty to Justice ..........................................................................7 Easing the Burden on New York City’s Carriage Horses.............................................................8 Lobbying to Save and Improve the Lives of Millions of Companion Animals...................................................................................9 Promoting Spay/Neuter and Adoption Programs to Limit the Number of Homeless Animals .............................................................................10 Finding Forever Homes for Companion Animals .....................................................................11 Providing Life-Saving Medical Services IN 2010, THE ASPCA® CONTINUED to Shelter Animals and Others ..............................................................................................12 Saving Lives in Poison-Related Emergencies .........................................................................13 TO EXTEND A HELPING HAND Scoring Gains in Partner Communities ..................................................................................14 TO ANIMALS AND ANIMAL WELFARE Strengthening the Bond Between Companion Animals and Their Humans .................................................................................16 -

The Ten O'clock News: Reported by Carol Marin

The Chicago Experiment – Journalist Attitudes and The Ten O’Clock News: Reported by Carol Marin Peter A. Casella A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: C.A. Tuggle, PhD, Chair David Cupp Richard Landesberg, PhD Patricia Parker, PhD ©2008 Peter A. Casella ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT PETER A. CASELLA: The Chicago Experiment – Journalist Attitudes and The Ten O’Clock News: Reported by Carol Marin (Under the direction of C.A. Tuggle, PhD) WBBM-TV, the CBS owned-and-operated television station in Chicago, embarked on what was called a “noble experiment” in television journalism in February 2000. The Ten O’Clock News: Reported by Carol Marin was a return to traditional, normative television journalism. The program, with respected journalist Carol Marin as the only anchor, was an attempt by station management to revive the moribund ratings of the late news broadcast with traditional hard news. Station management promised to stick with the new format for at least one year. Nine month later, amid even lower ratings, a new management team cancelled the experiment. This is the first academic investigation of that initiative. This qualitative study utilized data generated from long interviews with five principals of the news program. The findings provided great insight into the philosophies and attitudes that shaped the broadcast, and revealed some of the things that caused the program’s demise. They also revealed a clear and definite attitude of antagonism that varied according to job responsibilities and position in the editorial hierarchy. -

Influencing Election

A PUBLICATION OF THE SILHA CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF MEDIA ETHICS AND LAW | FALL 2016 Facebook Confronts Questions, Criticisms over News Distribution, Censorship, and “Fake News” Influencing Election uring the autumn of 2016, social media giant individuals would remain involved in the Trending section Facebook was the target of significant criticism of the site, but their roles would be reduced to ensuring that for its role as a distributor of news to the public. the algorithm was working properly. In August 2016, Facebook replaced its human Quartz reported that Facebook’s decision to rely upon an editors who curated the site’s “Trending” topics algorithm rather than human editors to choose topics came Dsection, a feature that provides users with topics and news after the social media site faced criticisms over political bias. that are currently popular on Facebook, with an algorithm In May, Gizmodo reported that Facebook’s human editors that would determine which topics should be featured. had regularly sought to suppress news topics that might be However, shortly after Facebook deployed the algorithm, of interest to conservatives. Although it denied the reports, a fake news story was promoted in the Trending stories Facebook faced significant criticisms in conservative news section, prompting significant criticism. Facebook faced circles, and the news prompted Sen. John Thune (R-S.D.), more controversy in September after it removed a Pulitzer the chairman of the Senate’s Commerce, Science, and Prize-winning Vietnam war photograph from a Norwegian Transportation Committee, to send a letter to Facebook newspaper’s page. In November, Facebook again found itself CEO Mark Zuckerberg asking him to explain whether the in crosshairs as critics accused the social media company company had sought to suppress conservative viewpoints. -

Joel Cheatwood, VP, News, WSVN-TV Miami, Named Senior VP, Sunbeam Television Corporation, There. Francisco: Doug Mcconnell, Host

Joel Cheatwood, VP, news, joins as weekend meteorologist. Val Maki, GSM, WCDJ-FM Boston, WSVN-TV Miami, named senior VP, Mark Pettinger, general assign- joins WKQX-FM Chicago in same ca- Sunbeam Television Corporation, ment reporter, KTSM-TV El Paso, pacity. there. Tex., joins WAVE-TV Louisville, Appointments at WASH-FM Wash- Ky., in same capacity. ington: John Steele, production direc- Appointments at KRON-TV San tor, named midday personality; Francisco: Doug McConnell, host. Kevin Kelly, director, news, pub- lic affairs, WTRG-FM Raleigh, N ,C., Randi Martin, announcer, WMGF-FM The Discovery Channel's The Ad- Orlando, Fla., joins as afternoon joins WLFL-TV there as news director. venturers, Bethesda, Md., joins as en- drive announcer. vironmental reporter/host, Bav Erv Coppi, host, Movie Theater, Area Backroads\ Henry Tenenbaum, Ron Aaron, morning drive talk WUSi-Tv OIney, 111., retires. feature reporter, named entertain- show host, KTSA(AM) San Antonio, ment reporter; Debra Chambers, ac- Mike Cavender, news director, Tex., joins WOAI(AM) there as after- counting manager, named control- WTSP-TV St. Petersburg/Tampa, noon drive talk show host. Joel Cheatwood Henry Tenenbaum Al Holzer Vicki Stearn Krista Van Lewen Sunbeam KRON-TV KRON-TV Discovery Comm. Inc. Discovery Comm. Inc. ler; Al Holzer, news director, named named VP, news. Spencer Shiftman, sales agent, VP, news programing, creative ser- Daum Commercial Real Estate, Los vices; Mark Murray, director, fi- RADIO Angeles, joins Christal Radio there nance, business affairs, named VP, as account executive. finance business; Jan Van Der Appointments at Shamrock Broad- Kristin Farrell, media buyer/su- Voort, VP, human resources, as- casting, Burbank, Calif.: Eddie Es- pervisor, Bozell, Dallas, joins Banner sumes additional responsibilities for serman, GM, WFOX-FM Gaines- Radio there as account executive.