Persian Propaganda — a Neglected Factor in Xerxes' Invasion of Greece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iranian Coins & Mints: Achaemenid Dynasty

IRANIAN COINS & MINTS: ACHAEMENID DYNASTY DARIC The Achaemenid Currency By: Michael Alram DARIC (Gk. dareiko‚s statê´r), Achaemenid gold coin of ca. 8.4 gr, which was introduced by Darius I the Great (q.v.; 522-486 B.C.E.) toward the end of the 6th century B.C.E. The daric and the similar silver coin, the siglos (Gk. síglos mediko‚s), represented the bimetallic monetary standard that the Achaemenids developed from that of the Lydians (Herodotus, 1.94). Although it was the only gold coin of its period that was struck continuously, the daric was eventually displaced from its central economic position first by the biga stater of Philip II of Macedonia (359-36 B.C.E.) and then, conclusively, by the Nike stater of Alexander II of Macedonia (336-23 B.C.E.). The ancient Greeks believed that the term dareiko‚s was derived from the name of Darius the Great (Pollux, Onomastikon 3.87, 7.98; cf. Caccamo Caltabiano and Radici Colace), who was believed to have introduced these coins. For example, Herodotus reported that Darius had struck coins of pure gold (4.166, 7.28: chrysíou statê´rôn Dareikôn). On the other hand, modern scholars have generally supposed that the Greek term dareiko‚s can be traced back to Old Persian *dari- "golden" and that it was first associated with the name of Darius only in later folk etymology (Herzfeld, p. 146; for the contrary view, see Bivar, p. 621; DARIUS iii). During the 5th century B.C.E. the term dareiko‚s was generally and exclusively used to designate Persian coins, which were circulating so widely among the Greeks that in popular speech they were dubbed toxo‚tai "archers" after the image of the figure with a bow that appeared on them (Plutarch, Artoxerxes 20.4; idem, Agesilaus 15.6). -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Ancient Greek Coins

Ancient Greek Coins Notes for teachers • Dolphin shaped coins. Late 6th to 5th century BC. These coins were minted in Olbia on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine. From the 8th century BC Greek cities began establishing colonies around the coast of the Black Sea. The mixture of Greek and native currencies resulted in a curious variety of monetary forms including these bronze dolphin shaped items of currency. • Silver stater. Aegina c 485 – 480 BC This coin shows a turtle symbolising the naval strength of Aegina and a punch mark In Athens a stater was valued at a tetradrachm (4 drachms) • Silver staterAspendus c 380 BC This shows wrestlers on one side and part of a horse and star on the other. The inscription gives the name of a city in Pamphylian. • Small silver half drachm. Heracles wearing a lionskin is shown on the obverse and Zeus seated, holding eagle and sceptre on the reverse. • Silver tetradrachm. Athens 450 – 400 BC. This coin design was very poular and shows the goddess Athena in a helmet and has her sacred bird the Owl and an olive sprig on the reverse. Coin values The Greeks didn’t write a value on their coins. Value was determined by the material the coins were made of and by weight. A gold coin was worth more than a silver coin which was worth more than a bronze one. A heavy coin would buy more than a light one. 12 chalkoi = 1 Obol 6 obols = 1 drachm 100 drachma = 1 mina 60 minas = 1 talent An unskilled worker, like someone who unloaded boats or dug ditches in Athens, would be paid about two obols a day. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict?

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict? Maria Natasha Ioannou Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy Discipline of Classics School of Humanities The University of Adelaide December 2012 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................ III Declaration........................................................................................................... IV Acknowledgements ............................................................................................. V Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1. Overview .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Background and Context ................................................................................. 1 3. Thesis Aims ..................................................................................................... 3 4. Thesis Summary .............................................................................................. 4 5. Literature Review ............................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: Cyprus Considered .......................................................................... 14 1.1 Cyprus’ Internal Dynamics ........................................................................... 15 1.2 Cyprus, Phoenicia and Egypt ..................................................................... -

The Tyrannies in the Greek Cities of Sicily: 505-466 Bc

THE TYRANNIES IN THE GREEK CITIES OF SICILY: 505-466 BC MICHAEL JOHN GRIFFIN Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Classics September 2005 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to thank the Thomas and Elizabeth Williams Scholarship Fund (Loughor Schools District) for their financial assistance over the course of my studies. Their support has been crucial to my being able to complete this degree course. As for academic support, grateful thanks must go above all to my supervisor at the School of Classics, Dr. Roger Brock, whose vast knowledge has made a massive contribution not only to this thesis, but also towards my own development as an academic. I would also like to thank all other staff, both academic and clerical, during my time in the School of Classics for their help and support. Other individuals I would like to thank are Dr. Liam Dalton, Mr. Adrian Furse and Dr. Eleanor OKell, for all their input and assistance with my thesis throughout my four years in Leeds. Thanks also go to all the other various friends and acquaintances, both in Leeds and elsewhere, in particular the many postgraduate students who have given their support on a personal level as well as academically. -

An Introduction to Old Persian Prods Oktor Skjærvø

An Introduction to Old Persian Prods Oktor Skjærvø Copyright © 2016 by Prods Oktor Skjærvø Please do not cite in print without the author’s permission. This Introduction may be distributed freely as a service to teachers and students of Old Iranian. In my experience, it can be taught as a one-term full course at 4 hrs/w. My thanks to all of my students and colleagues, who have actively noted typos, inconsistencies of presentation, etc. TABLE OF CONTENTS Select bibliography ................................................................................................................................... 9 Sigla and Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................... 12 Lesson 1 ..................................................................................................................................................... 13 Old Persian and old Iranian. .................................................................................................................... 13 Script. Origin. .......................................................................................................................................... 14 Script. Writing system. ........................................................................................................................... 14 The syllabary. .......................................................................................................................................... 15 Logograms. ............................................................................................................................................ -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

1 UNIT 3 the SOPHISTS Contents 3.0. Objectives 3.1. Introduction 3.2

UNIT 3 THE SOPHISTS Contents 3.0. Objectives 3.1. Introduction 3.2. Protagoras 3.3. Prodicus 3.4. Hippias 3.5. Gorgias 3.6. The Lesser Sophists 3.7. Let Us Sum Up 3.8. Key Words 3.9. Further Readings and References 3.10. Answers to Check Your Progress 3.0. OBJECTIVES In this Unit we explain in detail the Sophist movement and their philosophical insights that abandoned all abstract, metaphysical enquiries concerning the nature of the cosmos and focused on the practical issues of life. By the end of this Unit you should know: Their foul or fair argumentation Epistemological and ethical skepticism and relativism of the Sophists The differentiation between the early philosophers and Sophists The basic philosophical positions of Protagoras, Prodicus, Hippias and Gorgias 3.1. INTRODUCTION Sophist movement flourished in 5th century B.C., shortly before the emergence of the Socratic period. Xenophon, a historian of 4th century B.C., describes the Sophists as wandering teachers 1 who offered wisdom for sale in return for money. The Sophists were, then, professional teachers, who travelled about, from city to city, instructing people, especially the youth. They were paid large sums of money for their job. Until then teaching was considered something sacred and was not undertaken on a commercial basis. The Sophists claimed to be teachers of wisdom and virtue. These terms, however, did not have their original meaning in sophism. What they meant by these terms was nothing but a proficiency or skillfulness in practical affairs of daily life. This, they claimed, would lead people to success in life, which, according to them, consisted in the acquisition and enjoyment of material wealth as well as positions of power and influence in society. -

The Persian Wars: Ionian Revolt the Ionian Revolt, Which Began in 499

The Persian Wars: Ionian Revolt The Ionian Revolt, which began in 499 B.C. marked the beginning of the Greek-Persian wars. In 546 B.C. the Persians had conquered the wealthy Greek settlements in Ionia (Asia Minor). The Persians took the Ionians’ farmland and harbors. They forced the Ionians to pay tributes (the regular payments of goods). The Ionians also had to serve in the Persian army. The Ionians knew they could not defeat the Persians by themselves, so they asked mainland Greece for help. Athens sent soldiers and a small fleet of ships. Unfortunately for the Ionians, the Athenians went home after their initial success, leaving the small Ionian army to fight alone. In 493 B.C. the Persian army defeated the Ionians. To punish the Ionians for rebelling, the Persians destroyed the city of Miletus. They may have sold some of tis people into slavery. The Persian Wars: Battle of Marathon After the Ionian Revolt, the Persian King Darius decided to conquer the city-states of mainland Greece. He sent messengers to ask for presents of Greek earth and water as a sign that the Greeks agreed to accept Persian rule. But the Greeks refused. Darius was furious. In 490 B.C., he sent a large army of foot soldiers and cavalry (mounted soldiers) across the Aegean Sea by boat to Greece. The army assembled on the pain of Marathon. A general named Miltiades (Mill-te-ah-deez) convinced the other Greek commanders to fight the Persians at Marathon. In need of help, the Athenians sent a runner named Pheidippides (Fa-dip-e-deez) to Sparta who ran for two days and two nights. -

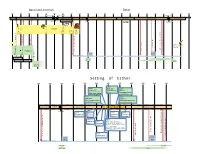

Setting of Esther

Daniel and Jeremiah Esther 610 600 590 580 570 560 550 540 530 520 510 500 490 480 470 460 450 440 430 420 410 400 Amel-marduk 561-560 Labashi-marduk 556 Xerxes II 425-424 Cambyses Nabopolassar Nebuchadnezzar 605-562 Nabonidus 556-536 Cyrus 539-530 Darius I 521-486 Xerxes I 486-465 Artaxerxes I 465-424 Darius II 423-404 625-605 529-522 Nergal-shal-usur 559-557 Belshazzar 553-539 Smerdis 522 ESTHER Sogdianus 424-423 DANIEL 12 - 8 - Dan 3 Dan Dan 2 Dan 4 Dan 7 Dan 6, 9 5, Dan 10 Dan The The statue dream, 604 Fiery furnace, c603 The tree dream, c571 Vision of four beasts, 553 Vision of ram &goat, 551 Fall of Babylon, 539 Lion’s den Reading of Jeremiah, 539 Vision of the end, 536 , 538 , Deportation, Deportation, 605 st 1 Deportation, 597 Deportation, Deportation, 587 Deportation, Sheshbazzar nd rd Letters sent from Jews at 2 3 Elephantine to Yohanan, high priest in Jerusalem, 410 and 407 Nehemiah returned to Artaxerxes, Artaxerxes, 433 Nehemiah toreturned visit of Nehemiah, Nehemiah, 432 visit of visit of Nehemiah, 445 visitof Nehemiah, return, return, led by st nd Return of Ezra, 458 of Return Ezra, 1 2 st JEREMIAH 1 Walls of 29 25 Temple Jerusalem rebuilt Jer Jer Message Message to exiles, 597 Prophecy Prophecy of captivity, 605 rebuilt, Temple foundation laid 520-516 443 Jehoiakim 609-598 HAGGAI NEHEMIAH Jehoiachin 608-597 Zedekiah 597-587 flight585 to Forced Egypt, ZECHARIAH EZRA MALACHI 44 Jer Prophecy Prophecy against refugees in Egypt Setting of Esther 540 530 520 510 500 490 480 470 460 450 440 430 478 BC 482 BC Esther 2:16 474