Unstable Biographies. the Ethnography of Memory And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guerra Em Angola As Heranças Da Luta De Libertação E a Guerra Civil

ACADEMIA MILITAR DIRECÇÃO DE ENSINO Mestrado em Ciências Militares – Especialidade de Cavalaria Trabalho de Investigação Aplicada GUERRA EM ANGOLA AS HERANÇAS DA LUTA DE LIBERTAÇÃO E A GUERRA CIVIL Elaborado por: Asp Tir Cav Feliciano Paulo Agostinho (RA) Orientador: TCor Cav Francisco Amado Rodrigues Lisboa, Setembro de 2011 ACADEMIA MILITAR DIRECÇÃO DE ENSINO Mestrado em Ciências Militares – Especialidade de Cavalaria Trabalho de Investigação Aplicada GUERRA EM ANGOLA AS HERANÇAS DA LUTA DE LIBERTAÇÃO E A GUERRA CIVIL Elaborado por: Asp Cav Feliciano Paulo Agostinho (RA) Orientador: TCor Cav Francisco Amado Rodrigues Lisboa, Setembro de 2011 DEDICATÓRIA À minha família, em especial à minha mãe, esposa e filha. Muito obrigado pelo amor, carinho e apoio prestados. GUERRA EM ANGOLA - AS HERANÇAS DA LUTA DE LIBERTAÇÃO E A GUERRA CIVIL iii AGRADECIMENTOS Manifesto o contentamento por todo o apoio prestado à realização deste trabalho de investigação. O meu muito obrigado: Ao Comandante da Academia Militar, Tenente-General Paiva Monteiro, por permitir que esta investigação fosse possível; Ao Tenente-Coronel de Cavalaria Francisco Amado Rodrigues, meu orientador, por todo o esclarecimento e orientação concedidos; À direcção do curso de cavalaria, na pessoa do Tenente-Coronel de Cavalaria Henrique Mateus, pelo apoio, disponibilidade e partilha de conhecimentos; À Chancelaria de Angola em Portugal, pelo apoio material e financeiro prestado durante a sua realização; Ao Tenente-Coronel de Cavalaria Paulo Ramos, na ajuda da escolha do tema e na elaboração da questão principal; Ao Tenente-Coronel de Infantaria António Marracho, pelo apoio inicial, na definição e estrutura do trabalho; Ao Tenente de Artilharia Agostinho Silva, pela compreensão, apoio e dedicação; À Biblioteca Nacional do Palácio Gouveia e ao Museu da República e Resistência, por toda a atenção prestada durante as pesquisas; À Biblioteca da Academia Militar, em especial à Sra. -

Inventário Florestal Nacional, Guia De Campo Para Recolha De Dados

Monitorização e Avaliação de Recursos Florestais Nacionais de Angola Inventário Florestal Nacional Guia de campo para recolha de dados . NFMA Working Paper No 41/P– Rome, Luanda 2009 Monitorização e Avaliação de Recursos Florestais Nacionais As florestas são essenciais para o bem-estar da humanidade. Constitui as fundações para a vida sobre a terra através de funções ecológicas, a regulação do clima e recursos hídricos e servem como habitat para plantas e animais. As florestas também fornecem uma vasta gama de bens essenciais, tais como madeira, comida, forragem, medicamentos e também, oportunidades para lazer, renovação espiritual e outros serviços. Hoje em dia, as florestas sofrem pressões devido ao aumento de procura de produtos e serviços com base na terra, o que resulta frequentemente na degradação ou transformação da floresta em formas insustentáveis de utilização da terra. Quando as florestas são perdidas ou severamente degradadas. A sua capacidade de funcionar como reguladores do ambiente também se perde. O resultado é o aumento de perigo de inundações e erosão, a redução na fertilidade do solo e o desaparecimento de plantas e animais. Como resultado, o fornecimento sustentável de bens e serviços das florestas é posto em perigo. Como resposta do aumento de procura de informações fiáveis sobre os recursos de florestas e árvores tanto ao nível nacional como Internacional l, a FAO iniciou uma actividade para dar apoio à monitorização e avaliação de recursos florestais nationais (MANF). O apoio à MANF inclui uma abordagem harmonizada da MANF, a gestão de informação, sistemas de notificação de dados e o apoio à análise do impacto das políticas no processo nacional de tomada de decisão. -

The Botanical Exploration of Angola by Germans During the 19Th and 20Th Centuries, with Biographical Sketches and Notes on Collections and Herbaria

Blumea 65, 2020: 126–161 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/blumea RESEARCH ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.3767/blumea.2020.65.02.06 The botanical exploration of Angola by Germans during the 19th and 20th centuries, with biographical sketches and notes on collections and herbaria E. Figueiredo1, *, G.F. Smith1, S. Dressler 2 Key words Abstract A catalogue of 29 German individuals who were active in the botanical exploration of Angola during the 19th and 20th centuries is presented. One of these is likely of Swiss nationality but with significant links to German Angola settlers in Angola. The catalogue includes information on the places of collecting activity, dates on which locations botanical exploration were visited, the whereabouts of preserved exsiccata, maps with itineraries, and biographical information on the German explorers collectors. Initial botanical exploration in Angola by Germans was linked to efforts to establish and expand Germany’s plant collections colonies in Africa. Later exploration followed after some Germans had settled in the country. However, Angola was never under German control. The most intense period of German collecting activity in this south-tropical African country took place from the early-1870s to 1900. Twenty-four Germans collected plant specimens in Angola for deposition in herbaria in continental Europe, mostly in Germany. Five other naturalists or explorers were active in Angola but collections have not been located under their names or were made by someone else. A further three col- lectors, who are sometimes cited as having collected material in Angola but did not do so, are also briefly discussed. Citation: Figueiredo E, Smith GF, Dressler S. -

VI. O Acto Eleitoral

VI. O acto eleitoral No dia 5 de Setembro de 2008, em todas as Províncias do país, os angolanos levantaram-se cedo para exercerem o seu direito de voto. Infelizmente, cedo se descobriu que não seriam essas as eleições que se esperava viessem a ser exemplares para o Continente Africano e para o Mundo. Eis aqui um resumo das ocorrências fraudulentas que, em 5 de Setembro de 2008, caracterizaram o dia mais esperado do processo político, o dia D: 1. Novo mapeamento das Assembleias de Voto 1.1 O mapeamento inicialmente distribuído aos Partidos Políticos, assim como os locais de funcionamento das Assembleias de Voto e os cadernos de registo eleitoral, não foram publicitados com a devida antecedência, para permitir uma eleição ordeira e organizada. 1.2 Para agravar a situação, no dia da votação, o mapeamento dos locais de funcionamento das Assembleias de Voto produzido pela CNE não foi o utilizado. O mapeamento utilizado foi outro, produzido por uma instituição de tal modo estranha à CNE e que os próprios órgãos locais da CNE desconheciam. Em resultado, i. Milhares de eleitores ficaram sem votar; ii. Aldeias e outras comunidades tiveram de ser arregimentadas em transportes arranjados pelo Governo, para irem votar em condições de voto condicionado; iii. Não houve mecanismos fiáveis de controlo da observância dos princípios da universalidade e da unicidade do voto. 1.3 O Nº. 2 do Art.º 105 da Lei Eleitoral é bastante claro: “a constituição das Mesas fora dos respectivos locais implica a nulidade das eleições na Mesa em causa e das operações eleitorais praticadas nessas circunstâncias, salvo motivo de força maior, devidamente justificado e apreciado pelas instâncias judiciais competentes ou por acordo escrito entre a entidade municipal da Comissão Nacional Eleitoral e os delegados dos partidos políticos e coligações de partidos ou dos candidatos concorrentes.” 1.4 Em todos os casos que a seguir se descreve, foram instaladas Assembleias de Voto anteriormente não previstas. -

Entre Raças, Tribos E Nações: Os Intelectuais Do Centro De Estudos Angolanos, 1960-1980

Fábio Baqueiro Figueiredo Entre raças, tribos e nações: os intelectuais do Centro de Estudos Angolanos, 1960-1980 Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos Étnicos e Africanos da Universidade Federal da Bahia como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Doutor em Estudos Étnicos e Africanos. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Valdemir Donizette Zamparoni Salvador 2012 Biblioteca CEAO – UFBA F475 Fábio Baqueiro Figueiredo Entre raças, tribos e nações: os intelectuais do Centro de Estudos Angolanos, 1960-1980 / por Fábio Baqueiro Figueiredo. — 2012. 439 p. Orientador : Prof. Dr. Valdemir Donizette Zamparoni. Tese (doutorado) — Universidade Federal da Bahia, Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Programa Multidisciplinar de Pós-Graduação em Estudos Étnicos e Africanos, 2012. 1. Angola — História — Revolução, 1961-1975. 2. Angola — História — Guerra civil, 1975-2002. 3. Nacionalismo e literatura — Angola. 4. Relações raciais. I. Zamparoni, Valdemir, 1957-. II. Universidade Federal da Bahia. Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. III. Título. CDD - 967.303 Fábio Baqueiro Figueiredo Entre raças, tribos e nações: os intelectuais do Centro de Estudos Angolanos, 1960-1980 Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos Étnicos e Africanos da Universidade Federal da Bahia como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Doutor em Estudos Étnicos e Africanos. Aprovada em 4 de dezembro de 2012 Banca examinadora: Valdemir Donizette Zamparoni Universidade Federal da Bahia Doutor em História (Universidade de São Paulo) Carlos Moreira Henriques Serrano Universidade de São Paulo Doutor em Antropologia Social (Universidade de São Paulo) Cláudio Alves Furtado Universidade Federal da Bahia Doutor em Sociologia (Universidade de São Paulo) Inocência Luciano dos Santos Mata Universidade de Lisboa Doutora em Letras (Universidade de Lisboa) Maria de Fátima Ribeiro Universidade Federal da Bahia Doutora em Comunicação e Cultura Contemporânea (Universidade Federal da Bahia) Ibi Oyà wà, ló gbiná. -

Estudodemercado AIP Cabinda.Pdf

1 Mensagem do Presidente da Associação Industrial Portuguesa - Confederação Empresarial Angola e Portugal estão hoje em condições de cimentar uma grande parceria para o investimento, para o comércio e para os mercados, sustentada na valorização da língua comum, nas relações históricas e nas afinidades culturais. Estes factores configuram vantagens que podem ser exploradas e aproveitadas pelas duas partes para incrementarem as relações bilaterais, para desenvolverem estratégias colaborativas, redes de negócio e para uma acção conjunta nos mercados lusófonos e mesmo em relação a mercados terceiros. Para o efeito, é da maior importância a constituição de redes de conhecimento na actividade empresarial. Foi esta, a razão subjacente à elaboração dos estudos sobre as províncias de Benguela, Cabinda, Huambo, Huíla e Luanda que a AIP-CE decidiu realizar. Na verdade, para agir de forma inteligente nos mercados, é necessário coligir informação, estudá-los e conhecê-los. Devo sublinhar que esse exercício de estudar os mercados, muito particularmente o angolano, sempre fez parte das orientações da AIP-CE, mesmo nos períodos mais conturbados da vida política e social angolana, que felizmente já pertencem ao passado, tendo desenvolvido sobre este mercado, entre outros, guias de investimento, estudos sectoriais e regionais. Dando expressão a esta boa tradição da AIP-CE, creio que os Estudos de mercado sobre as Províncias Angolanas constituem um bom trabalho de caracterização da actividade económica destas províncias, mas também de prospectiva, de definição de prioridades em matéria de economia e de localização industrial, de sinalização de infraestruturas de apoio à actividade económica, de identificação de grandes projectos, enfim um bom instrumento de inteligência competitiva ao dispor dos empresários e das instituições portuguesas e angolanas. -

Weekly Polio Eradication Update

Angola Polio Weekly Update Week 42/2012 - Data updated as of 21st October - * Data up to Oct 21 Octtoup Data * Reported WPV cases by month of onset and SIAs, and SIAs, of onset WPV cases month by Reported st 2012 2008 13 12 - 11 2012* 10 9 8 7 WPV 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Jul-08 Jul-09 Jul-10 Jul-11 Jul-12 Jan-08 Jun-08 Oct-08 Jan-09 Jun-09 Oct-09 Jan-10 Jun-10 Oct-10 Jan-11 Jun-11 Oct-11 Jan-12 Jun-12 Feb-08 Mar-08 Apr-08 Feb-09 Mar-09 Apr-09 Feb-10 Mar-10 Apr-10 Fev-11 Mar-11 Apr-11 Feb-12 Mar-12 Apr-12 Sep-08 Nov-08 Dec-08 Sep-09 Nov-09 Dec-09 Sep-10 Nov-10 Dez-10 Sep-11 Nov-11 Dec-11 Sep-12 May-08 Aug-08 May-09 Aug-09 May-10 Aug-10 May-11 Aug-11 May-12 Aug-12 Wild 1 Wild 3 mOPV1 mOPV3 tOPV Angola bOPV AFP Case Classification Status 22 Oct 2011 to 21 Oct 2012 290 Reported Cases 239 3 43 5 0 Discarded Not AFP Pending Compatible Wild Polio Classification 27 0 16 Pending Pending Pending final Lab Result ITD classification AFP Case Classification by Week of Onset 22 Oct 2011 to 21 Oct 2012 16 - 27 pending lab results - 16 pending final classification 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 43 44 45 46 48 49 50 51 52 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 Pending_Lab Pending_Final Class Positive Compatible Discarded Not_AFP National AFP Surveillance Performance Twelve Months Rolling-period, 2010-2012 22 Oct 2010 to 21 Oct 2011 22 Oct 2011 to 21 Oct 2012 NP AFP ADEQUACY NP AFP ADEQUACY PROVINCE SURV_INDEX PROVINCE SURV_INDEX RAT E RAT E RAT E RAT E BENGO 4.0 100 4.0 BENGO 3.0 75 2.3 BENGUELA 2.7 -

Angola Rapid Assessment and Gap Analysis: ANGOLA

Rapid Assessment Gap Analysis Angola Rapid Assessment and Gap Analysis: ANGOLA September 2015 Rapid Assessment and Gap Analysis - Angola Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Section 1: Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 16 1.1. Country Overview ..................................................................................................................................... 16 1.1.1. Geography and Demography overview ............................................................................................... 16 1.1.2. Political, economic and socio-economic conditions ............................................................................ 18 1.2. Energy Situation ........................................................................................................................................ 20 1.2.1. Energy Resources ................................................................................................................................. 20 1.2.1.1. Oil and Natural Gas -

Resumo Cadastros Por Provincia República De Angola

RESUMO CADASTROS POR PROVINCIA REPÚBLICA DE ANGOLA PROVINCIA MUNICIPIO COMUNA Nº AGREGADOS Nº MEMBROS Bengo Dande (Caxito) Mabubas 107 284 TOTAL PROVINCIA: 107 284 Bié Camacupa Camacupa 2 8 Camacupa Umpulo 1 4 Catabola Caiuera 296 686 Catabola Catabola 830 1945 Catabola Chipeta 3255 11157 Catabola Chiuca 91 150 Catabola Sande 80 195 Chinguar Cangala 1192 4349 Chinguar Cangote 372 1163 Chinguar Chinguar 709 2849 Chinguar Kutato 149 475 Chitembo Soma Cuanza 1 4 Kuito Chicala 1 1 Kuito Kuito 2 2 TOTAL PROVINCIA: 6981 22988 Cabinda Belize Belize 3 19 Buco Zau Buco Zau 1 2 Cabinda Cabinda 275 859 Cabinda Malembo 3 7 Cabinda Tando Zinze 2 7 TOTAL PROVINCIA: 284 894 Cuando-Cubango Menongue Cueio 264 1114 Menongue Menongue 4 7 Menongue Missombo 1 1 TOTAL PROVINCIA: 269 1122 Luanda Belas Cabolombo 3 4 Belas Kilamba 7 11 Belas Quenguela 2 2 Belas Ramiros 17 27 Belas Vila Verde 4 6 Cacuaco Cacuaco 25 40 Cacuaco Funda 8 9 Cacuaco Kikolo 8 10 Cacuaco Mulenvos de Baixo 2 2 Cacuaco Sequele 13 22 Cazenga Cazenga 36 52 Cazenga Hoji Ya Henda 10 15 Cazenga Kalawenda 4 7 Cazenga Kima Kieza 2 4 Cazenga Tala Hadi 14 17 SIGAS - Sistema de Informação e Gestão da Acção Social Página 1 de 3 15/05/2019 15:35:30 fernanda.almeida RESUMO CADASTROS POR PROVINCIA REPÚBLICA DE ANGOLA PROVINCIA MUNICIPIO COMUNA Nº AGREGADOS Nº MEMBROS Luanda Icolo Bengo Bela Vista 2 8 Icolo Bengo Bom Jesus 1 2 Icolo Bengo Catete 1 2 Kilamba Kiaxi Golfe 54 78 Kilamba Kiaxi Nova Vida 5 7 Kilamba Kiaxi Palanca 13 15 Kilamba Kiaxi Sapú 50 54 Luanda Ingombota 18 35 Luanda Maianga 67 115 Luanda -

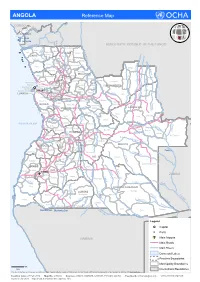

ANGOLA Reference Map

ANGOLA Reference Map CONGO L Belize ua ng Buco Zau o CABINDA Landana Lac Nieba u l Lac Vundu i Cabinda w Congo K DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO o z Maquela do Zombo o p Noqui e Kuimba C Soyo M Mbanza UÍGE Kimbele u -Kongo a n ZAIRE e Damba g g o id Tomboco br Buengas M Milunga I n Songo k a Bembe i C p Mucaba s Sanza Pombo a i a u L Nzeto c u a i L l Chitato b Uige Bungo e h o e d C m Ambuila g e Puri Massango b Negage o MALANGE L Ambriz Kangola o u Nambuangongo b a n Kambulo Kitexe C Ambaca m Marimba g a Kuilo Lukapa h u Kuango i Kalandula C Dande Bolongongo Kaungula e u Sambizanga Dembos Kiculungo Kunda- m Maianga Rangel b Cacuaco Bula-Atumba Banga Kahombo ia-Baze LUNDA NORTE e Kilamba Kiaxi o o Cazenga eng Samba d Ingombota B Ngonguembo Kiuaba n Pango- -Caju a Saurimo Barra Do Cuanza LuanCda u u Golungo-Alto -Nzoji Viana a Kela L Samba Aluquem Lukala Lul o LUANDA nz o Lubalo a Kazengo Kakuso m i Kambambe Malanje h Icolo e Bengo Mukari c a KWANZA-NORTE Xa-Muteba u Kissama Kangandala L Kapenda- L Libolo u BENGO Mussende Kamulemba e L m onga Kambundi- ando b KWANZA-SUL Lu Katembo LUNDA SUL e Kilenda Lukembo Porto Amboim C Kakolo u Amboim Kibala t Mukonda Cu a Dala Luau v t o o Ebo Kirima Konda Ca s Z ATLANTIC OCEAN Waco Kungo Andulo ai Nharea Kamanongue C a Seles hif m um b Sumbe Bailundo Mungo ag e Leua a z Kassongue Kuemba Kameia i C u HUAMBO Kunhinga Luena vo Luakano Lobito Bocoio Londuimbali Katabola Alto Zambeze Moxico Balombo Kachiungo Lun bela gue-B Catum Ekunha Chinguar Kuito Kamakupa ungo a Benguela Chinjenje z Huambo n MOXICO -

Angola Livelihood Zone Report

ANGOLA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions November 2013 ANGOLA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions November 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………................……….…........……...3 Acronyms and Abbreviations……….………………………………………………………………......…………………....4 Introduction………….…………………………………………………………………………………………......………..5 Livelihood Zoning and Description Methodology……..……………………....………………………......…….…………..5 Livelihoods in Rural Angola….………........………………………………………………………….......……....…………..7 Recent Events Affecting Food Security and Livelihoods………………………...………………………..…….....………..9 Coastal Fishing Horticulture and Non-Farm Income Zone (Livelihood Zone 01)…………….………..…....…………...10 Transitional Banana and Pineapple Farming Zone (Livelihood Zone 02)……….……………………….….....…………..14 Southern Livestock Millet and Sorghum Zone (Livelihood Zone 03)………….………………………….....……..……..17 Sub Humid Livestock and Maize (Livelihood Zone 04)…………………………………...………………………..……..20 Mid-Eastern Cassava and Forest (Livelihood Zone 05)………………..……………………………………….……..…..23 Central Highlands Potato and Vegetable (Livelihood Zone 06)..……………………………………………….………..26 Central Hihghlands Maize and Beans (Livelihood Zone 07)..………..…………………………………………….……..29 Transitional Lowland Maize Cassava and Beans (Livelihood Zone 08)......……………………...………………………..32 Tropical Forest Cassava Banana and Coffee (Livelihood Zone 09)……......……………………………………………..35 Savannah Forest and Market Orientated Cassava (Livelihood Zone 10)…….....………………………………………..38 Savannah Forest and Subsistence Cassava -

Unhcr Special Funding Appeal for Unhcr's Supplementary Programme

UNHCR SPECIAL FUNDING APPEAL FOR UNHCR’S SUPPLEMENTARY PROGRAMME TO PROVIDE EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE TO INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS IN ANGOLA (IN THE PROVINCES OF UIGE, ZAIRE & LUANDA) June - December 2000 UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES July 2000 For additional copies, please contact: UNHCR Donor Relations & Resource Mobilisation Service 94, rue de Montbrillant CH-1202 Geneva Tel.: (41 22) 739 7730 Fax.: (41 22) 739 7351 Email.: buss @unhcr.ch TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. BACKGROUND / INTRODUCTION 1 2. OBJECTIVES 3 2.1. Principal goals 2.2. Assumptions, Constraints and Opportunities 4 3. BENEFICIARIES 5 4. THE ROLE OF UNHCR, THE GOVERNMENT AND OTHER AGENCIES IN ANGOLA 5 4.1. The role of UNHCR and the Government 4.2. Collaboration with UN agencies, ICRC and NGOs 6 5. MANAGEMENT AND OVERALL CO-ORDINATION 7 6. OPERATIONAL STRATEGY 8 6.1. Protection goals and strategy 6.2. Material assistance goals and strategy 6.3. Implementation strategy 9 7. ACTIVITIES AND ASSISTANCE 9 7.1. Protection, Monitoring and Co-ordination 7.2. Legal Assistance / Protection 10 8. FUNDING 13 9. FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS / BUDGET 14 10. MAP 15 1. BACKGROUND/INTRODUCTION Following the collapse of the Lusaka Peace process in mid-1998, Angola descended once again into widespread armed conflict between the Government and UNITA. By the end of 1999, some 3.7 million Angolans (one third of a national population of 12.6 million), of whom 1.5 were internally displaced persons, were verified to be in need of humanitarian assistance. Massed in congested camp-like conditions and ravaged by disease and hunger, Angola’s displaced people in particular have become the victims of some of the most appalling, life-threatening conditions witnessed anywhere in the world today.