The Third Way of Neoconservatism: an Analysis of the Political

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presidential Emergency Facility Site 6 - “Cadre/Creed” on Raven Rock Mountain Near Blue Ridge Summit Pa

Presidential Emergency Facility Site 6 - “Cadre/Creed” On Raven Rock Mountain near Blue Ridge Summit Pa. Raven Rock Mountain Complex Raven Rock, Site of Creed Tower a PEF Elevation 1,516 feet (462.08m) Location Location Adams County, Pa Range Blue Ridge Summit USGS quad Coordinates +39° 44' 2.40", -77° 25' 8.40" The Raven Rock Mountain Complex (RRMC) is a United States government facility on Raven Rock, a mountain in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. It is located about 14 km (8.7 miles) east of Waynesboro, Pennsylvania, and 10 km (6.2 miles) north-northeast of Camp David, Maryland. It is also called the Raven Rock Military Complex, or simply Site R. Colloquially, the facility is known as an "underground Pentagon". Ravens Rock is also the site of a deactivated microwave terminal, which was used during the Cold War. The unit was encased in a mostly underground tower, and known as "Creed” site 6. The site was deactivated in 1977. It was connected to Site R: but, access is still restricted. Microwave Radio Terminal Site Site 6 - "Cadre/Creed" Tower History and Purpose "Site-R" is the location designator for a major US military bunker located inside Raven Rock Mountain, next to the community of Fountain Dale, near Blue Ridge Summit in Adams County Pennsylvania. The complex is also known as "the underground Pentagon," and affectionately to its personnel as "the Rock" or "the Hole" but the official name is the Alternate Joint Communications Center (AJCC). Planning for the site began in 1948. After the Soviet Union detonated its first nuclear weapon in 1949, a high priority was established for the Joint Command Post to be placed in a protected location near Washington, D.C. -

Albert Wohlstetter's Legacy: the Neo-Cons, Not Carter, Killed

SPECIAL REPORT: NUCLEAR SABOTAGE ALBERT WOHLSTETTER’S LEGACY Wohlstetter was even stranger than the “Dr. Strangelove” depicted in the 1964 movie of that name. An early draft of the film was titled “The Delicate Balance of Terror,” the same title as Wohlstetter’s best-known unclassified work. Here, a still from the film. tives—Paul Wolfowitz, Richard Perle, and Zalmay Khalilzad, to name a few. In Wohlstetter’s circle of influence were also Ahmed Chalabi (whom Wohlstetter championed), Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson (D-Wash.), Sen. Robert Dole (R- Kan.), and Margaret Thatcher. Wohlstetter himself was a follower of Bertrand Russell, not only in mathematics, but in world outlook. The pseudo-peacenik Russell had called for a preemptive strike against the Soviet Union, after World War II and before the Soviets developed the bomb, as a prelude to his plan for bully- ing nations into a one-world government. Russell, a raving Malthusian, opposed economic development, especially in the Third World. Admirer Jude Wanniski wrote of Wohlstetter in an obituary, “[I]t is no exaggeration, I think, to say that Wohlstetter was the most influential unknown man in the world for the past half century, and easily in the top ten in importance of all men.” “Albert’s decisions were not automat- ically made official policy at the White House,” Wanniski wrote, “but Albert’s The Neo-Cons, Not Carter, genius and his following were such in the places where it counted in the Establishment that if his views were Killed Nuclear Energy resisted for more than a few months, it -

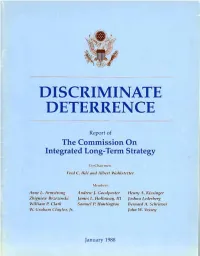

Discriminate Deterrence

DISCRIMINATE DETERRENCE Report of The Commission On Integrated Long-Term Strategy Co -C. I lairmea: Fred C. lkle and Albert Wohlstetter Moither, Anne L. Annsinmg Andrew l. Goodraster flenry /1 Kissinger Zbign ei Brzezinski fames L. Holloway, Ur Joshua Lederberg William P. Clark Samuel P. Huntington Bernard A. Schriever tV. Graham Ciaytor, John W. Vessey January 1988 COMMISSION ON INTEGRATED LONG-TERM STRATEGY January 11. 1988 MEMORANDUM FOR: THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE THE ASSISTANT TO THE PRESIDENT FOR NATIONAL SECURITY AFFAIRS We are pleased to present this final report of Our Commission. Pursuant to your initial mandate, the report proposes adjustments to US. military strategy in view of a changing security environment in the decades ahead. Over the last fifteen months the Commission has received valuable counsel from members of Congress, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Service Chiefs. and the Presdent's Science Advisor, Members of the National Security Council Staff, numerous professionals in the Department of Defense and the Central Intelligence Agency, and a broad range of specialists outside the government provided unstinting support. We are also indebted to the Commission's hardworking staff. The Commission was supported generously by several specialized study groups that closely analyzed a number of issues, among them: the security environment for the next twenty years, the role of advanced technology in military systems, interactions between offensive and defensive systems on the periphery of the Soviet Union, and the U.S, posture in regional conflicts around the world. Within the next few months, these study groups will publish detailed findings of their own. -

Reaching Beyond the Ivory Tower: a “How To” Manual *

Reaching Beyond the Ivory Tower: A “How To” Manual * Daniel Byman and Matthew Kroenig Security Studies (forthcoming, June 2016) *For helpful comments on earlier versios of this article, the authors would like to thank Michael C. Desch, Rebecca Friedman, Bruce Jentleson, Morgan Kaplan, Marc Lynch, Jeremy Shapiro, and participants in the Program on International Politics, Economics, and Security Speaker Series at the University of Chicago, participants in the Nuclear Studies Research Initiative Launch Conference, Austin, Texas, October 17-19, 2013, and members of a Midwest Political Science Association panel. Particular thanks to two anonymous reviewers and the editors of Security Studies for their helpful comments. 1 Joseph Nye, one of the rare top scholars with experience as a senior policymaker, lamented “the walls surrounding the ivory tower never seemed so high” – a view shared outside the academy and by many academics working on national security.1 Moreover, this problem may only be getting worse: a 2011 survey found that 85 percent of scholars believe the divide between scholars’ and policymakers’ worlds is growing. 2 Explanations range from the busyness of policymakers’ schedules, a disciplinary shift that emphasizes theory and methodology over policy relevance, and generally impenetrable academic prose. These and other explanations have merit, but such recommendations fail to recognize another fundamental issue: even those academic works that avoid these pitfalls rarely shape policy.3 Of course, much academic research is not designed to influence policy in the first place. The primary purpose of academic research is not, nor should it be, to shape policy, but to expand the frontiers of human knowledge. -

Digest of Other White House Announcements

1862 Oct. 25 / Administration of George W. Bush, 2002 cultural development, and the building of de- October 21 mocracy and rule of law, bringing tangible In the morning, the President had intel- benefits to the Chinese people. Their quality ligence and FBI briefings and later met with of life and standard of living are improving. the National Security Council. As the biggest developing country in the In the evening, the President traveled to world, this road is still very long before China McLean, VA, where he attended a Repub- achieves full modernization. Our central task lican National Committee dinner at a private and long-term goal remain one of economic residence. He then returned to Washington, development and improvement of people’s DC. living standards. The Chinese people have a tradition of October 22 peace loving. China has never engaged in ex- In the morning, the President had FBI pansion nor sought hegemony. We sincerely briefings. Later, he traveled to desire peace all over the world. Even when Downingtown, PA. In the afternoon, he trav- China becomes more developed in the fu- eled to Bangor, ME, and later returned to ture, it will not pose a threat to others. Washington, DC. Threats have and will continue to prove that The White House announced that the China is a staunch force for the maintenance President will welcome Prime Minister Peter of world and regional peace. Medgyessy of Hungary to Washington, DC, Thank you. on November 8 to discuss cooperation President Bush. Thank you all very much. against terrorism, the upcoming NATO sum- mit in Prague, and other issues. -

National Security Advisor SAIGON EMBASSY FILES KEPT by AMBASSADOR GRAHAM MARTIN: Copies Made for the NSC, 1963-1975 (1976)

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library & Museum National Security Advisor SAIGON EMBASSY FILES KEPT BY AMBASSADOR GRAHAM MARTIN: Copies Made for the NSC, 1963-1975 (1976) SUMMARY DESCRIPTION Copies of State Department telegrams and White House backchannel messages between U.S. ambassadors in Saigon and White House national security advisers, talking points for meetings with South Vietnamese officials, intelligence reports, drafts of peace agreements, and military status reports. Subjects include the Diem coup, the Paris peace negotiations, the fall of South Vietnam, and other U.S./South Vietnam relations topics, 1963 to 1975. QUANTITY 4.0 linear feet (ca. 8000 pages) DONOR Gerald R. Ford (accession number 82-73) ACCESS Open. The collection is administered under terms of the donor's deed of gift, a copy of which is available on request, and under National Archives and Records Administration general restrictions (36 CFR 1256). COPYRIGHT President Ford has donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. Prepared by Karen B. Holzhausen, November 1992; Revised March 2000 [s:\bin\findaid\nsc\saigon embassy files kept by ambassador graham martin.doc] [This finding aid, found at https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/guides/findingaid/ nsasaigon.asp, was slightly adapted on pp. 6-7 by the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in July 2018 to serve as a guide to the microfilm edition published by Primary Source Media.] 2 VIETNAM WAR CHRONOLOGY (Related to this collection) August 21, 1963 Ngo Dinh Nhu's forces attack Buddhist temples. -

Interpretation: a Journal of Political Philosophy

Interpretation A JOURNAL A OF POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY Winter 1997 Volume 24 Number 2 135 Robert D. Sacks The Book of Job: Translation and Commentary 171 Marc D. Guerra Aristotle on Pleasure and Political Philosophy: A Study in Book VII of the Nicomachean Ethics 183 Mark S. Cladis Lessons from the Garden: Rousseau's Solitaires and the Limits of Liberalism 201 Thomas Heilke Nietzsche's Impatience: The Spiritual Necessities of Nietzsche's Politics Book Reviews 233 Eduardo A. Velasquez Profits, Priests, and Princes: Adam Smith 's Emancipation of Economics from Politics and Religion, by Peter Minowitz 239 Charles E. Butterworth Something To Hide, by Peter Levine 243 Will Morrisey Jerusalem and Athens: Reason and Revelation in the Works of Leo Strauss, by Susan Orr Interpretation Editor-in-Chief Hilail Gildin, Dept. of Philosophy, Queens College Executive Editor Leonard Grey General Editors Seth G. Benardete Charles E. Butterworth Hilail Gildin Robert Horwitz (d. 1987) Howard B. White (d. 1974) Consulting Editors Christopher Bruell Joseph Cropsey Ernest L. Fortin John Hallowell (d. 1992) Harry V. Jaffa David Lowenthal Muhsin Mahdi Harvey C. Mansfield Arnaldo Momigliano (d. 1987) Michael Oakeshott (d. 1990) Ellis Sandoz Leo Strauss (d. 1973) Kenneth W. Thompson International Editors Terence E. Marshall Heinrich Meier Editors Wayne Ambler Maurice Auerbach Fred Baumann Michael Blaustein Amy Bonnette Patrick Coby Thomas S. Engeman Edward J. Erler Maureen Feder-Marcus Pamela K. Jensen Ken Masugi Will Morrisey Susan Orr Charles T. Rubin Leslie G. Rubin Susan Shell Richard Velkley Bradford P. Wilson Michael Zuckert Catherine Zuckert Manuscript Editor Lucia B. Prochnow Subscriptions Subscription rates per volume (3 issues): individuals $29 libraries and all other institutions $48 students (four-year limit) $18 Single copies available. -

The BCCI Affair

The BCCI Affair A Report to the Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate by Senator John Kerry and Senator Hank Brown December 1992 102d Congress 2d Session Senate Print 102-140 This December 1992 document is the penultimate draft of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee report on the BCCI Affair. After it was released by the Committee, Sen. Hank Brown, reportedly acting at the behest of Henry Kissinger, pressed for the deletion of a few passages, particularly in Chapter 20 on "BCCI and Kissinger Associates." As a result, the final hardcopy version of the report, as published by the Government Printing Office, differs slightly from the Committee's softcopy version presented below. - Steven Aftergood Federation of American Scientists This report was originally made available on the website of the Federation of American Scientists. This version was compiled in PDF format by Public Intelligence. Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF INVESTIGATION ............................................................................... 21 THE ORIGIN AND EARLY YEARS OF BCCI .................................................................................................... 25 BCCI'S CRIMINALITY .................................................................................................................................. 49 BCCI'S RELATIONSHIP WITH FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS CENTRAL BANKS, AND INTERNATIONAL -

The Watergate Story (Washingtonpost.Com)

The Watergate Story (washingtonpost.com) Hello corderoric | Change Preferences | Sign Out TODAY'S NEWSPAPER Subscribe | PostPoints NEWS POLITICS OPINIONS BUSINESS LOCAL SPORTS ARTS & GOING OUT JOBS CARS REAL RENTALS CLASSIFIEDS LIVING GUIDE ESTATE SEARCH: washingtonpost.com Web | Search Archives washingtonpost.com > Politics> Special Reports 'Deep Throat' Mark Felt Dies at 95 The most famous anonymous source in American history died Dec. 18 at his home in Santa Rosa, Calif. "Whether ours shall continue to be a government of laws and not of men is now before Congress and ultimately the American people." A curious crime, two young The courts, the Congress and President Nixon refuses to After 30 years, one of reporters, and a secret source a special prosecutor probe release the tapes and fires the Washington's best-kept known as "Deep Throat" ... the burglars' connections to special prosecutor. A secrets is exposed. —Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox after his Washington would be the White House and decisive Supreme Court firing, Oct. 20, 1973 changed forever. discover a secret taping ruling is a victory for system. investigators. • Q&A Transcript: John Dean's new book "Pure Goldwater" (May 6, 2008) • Obituary: Nixon Aide DeVan L. Shumway, 77 (April 26, 2008) Wg:1 http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/special/watergate/index.html#chapters[6/14/2009 6:06:08 PM] The Watergate Story (washingtonpost.com) • Does the News Matter To Anyone Anymore? (Jan. 20, 2008) • Why I Believe Bush Must Go (Jan. 6, 2008) Key Players | Timeline | Herblock -

Introduction

NOTES Introduction 1. Robert Kagan to George Packer. Cited in Packer’s The Assassin’s Gate: America In Iraq (Faber and Faber, London, 2006): 38. 2. Stefan Halper and Jonathan Clarke, America Alone: The Neoconservatives and the Global Order (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004): 9. 3. Critiques of the war on terror and its origins include Gary Dorrien, Imperial Designs: Neoconservatism and the New Pax Americana (Routledge, New York and London, 2004); Francis Fukuyama, After the Neocons: America At the Crossroads (Profile Books, London, 2006); Ira Chernus, Monsters to Destroy: The Neoconservative War on Terror and Sin (Paradigm Publishers, Boulder, CO and London, 2006); and Jacob Heilbrunn, They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons (Doubleday, New York, 2008). 4. A report of the PNAC, Rebuilding America’s Defenses: Strategy, Forces and Resources for a New Century, September 2000: 76. URL: http:// www.newamericancentury.org/RebuildingAmericasDefenses.pdf (15 January 2009). 5. On the first generation on Cold War neoconservatives, which has been covered far more extensively than the second, see Gary Dorrien, The Neoconservative Mind: Politics, Culture and the War of Ideology (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1993); Peter Steinfels, The Neoconservatives: The Men Who Are Changing America’s Politics (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1979); Murray Friedman, The Neoconservative Revolution: Jewish Intellectuals and the Shaping of Public Policy (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2005); Murray Friedman ed. Commentary in American Life (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2005); Mark Gerson, The Neoconservative Vision: From the Cold War to the Culture Wars (Madison Books, Lanham MD; New York; Oxford, 1997); and Maria Ryan, “Neoconservative Intellectuals and the Limitations of Governing: The Reagan Administration and the Demise of the Cold War,” Comparative American Studies, Vol. -

Theoretical Framework

Ascendancy to Power – a Structural Realist Account of the Neo-Conservatives’ Rising Influence Over American Foreign Policy By Elvin Gjevori Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations and European Studies In Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations and European Studies Supervisor: Professor Erin Kristin Jenne CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2007 (17,238 words) i Abstract Neo-conservatism is a doctrine that has been increasingly analyzed and debated in the last years because of its growing influence on the foreign policy of the United States. Despite the growing body of scholarship on the movement, little or no attention has been paid to the structural causes of the neocons’ success in influencing U.S. foreign policy, with most authors focused on personalities and historical moments to account for their increasing influence on American foreign policy. In contrast to accounts that rely on historically contingent events, this thesis provides a structural realist account of the growing influence of the neo-conservative ideology on American foreign policy in the later part of the twentieth century and at the turn of the twenty-first century. The thesis shows that the ascendancy of neocons to power is best understood by analyzing the permissive structural conditions of the international system after the end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the USSR. CEU eTD Collection ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................................................II -

Hayek's the Constitution of Liberty

Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty An Account of Its Argument EUGENE F. MILLER The Institute of Economic Affairs contenTs The author 11 First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Foreword by Steven D. Ealy 12 The Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Lord North Street Summary 17 Westminster Editorial note 22 London sw1p 3lb Author’s preface 23 in association with Profile Books Ltd The mission of the Institute of Economic Affairs is to improve public 1 Hayek’s Introduction 29 understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society, by analysing Civilisation 31 and expounding the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. Political philosophy 32 Copyright © The Institute of Economic Affairs 2010 The ideal 34 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a PART I: THE VALUE OF FREEDOM 37 retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. 2 Individual freedom, coercion and progress A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. (Chapters 1–5 and 9) 39 isbn 978 0 255 36637 3 Individual freedom and responsibility 39 The individual and society 42 Many IEA publications are translated into languages other than English or are reprinted. Permission to translate or to reprint should be sought from the Limiting state coercion 44 Director General at the address above.