Together We Move: Exploring Belonging, Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Motivational Factors in a Socially Structured University Physical Activity Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theory of Robot Communication: I

Hoorn, J. F. (2018). Theory of robot communication: I. The medium is the communication partner. arXiv:cs, 2502565(v1), 1-21. 1 Theory of Robot Communication: I. The Medium is the Communication Partner Johan F. Hoorn1,2 1 Department of Computing and School of Design, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, 999077, Hong Kong. 2 Department of Communication Science, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 1081 HV, The Netherlands. Correspondence should be addressed to Johan F. Hoorn; [email protected] Abstract When people use electronic media for their communication, Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) theories describe the social and communicative aspects of people’s interpersonal transactions. When people interact via a remote-controlled robot, many of the CMC theses hold. Yet, what if people communicate with a conversation robot that is (partly) autonomous? Do the same theories apply? This paper discusses CMC theories in confrontation with observations and research data gained from human-robot communication. As a result, I argue for an addition to CMC theorizing when the robot as a medium itself becomes the communication partner. In view of the rise of social robots in coming years, I define the theoretical precepts of a possible next step in CMC, which I elaborate in a second paper. Introduction Currently, the development and application of social robots in real-life settings rapidly increases. Whereas robots initially were the domain of science-fiction, today, social robots are tried out in service-oriented professions in healthcare, education, and commerce (Broadbent, 2017). Habitually, general-purpose robots are readied for a particular task in a particular environment such as guidance through an exhibition or reception in a hotel (Broadbent, 2017). -

Newsletter for February 2019

St. Peter’s Press St. Peter’s Presbyterian Church - Spencertown, NY PO Box 14 | 5219 County Route 7 | Spencertown, NY 12165 Telephone: 518.392.3386 | Email: [email protected] Rev. Lynn Horan: Cell Phone 518-847-9115 | Email: [email protected] Website: http://saintpeterspc.org | Facebook: www.facebook.com/saintpeterspc February 2019 Greetings St. Peter’s, As we awaited our recent snow storm, I bundled up at home with a new book that I found in our church worship closet titled Winter: A Spiritual Biography of the Season. The book includes various reflections, poems and even sermons from famous and lesser-known writers, each sharing their thoughts on the spiritual terrain that this season offers. I was especially drawn to a sermon by Rev. William Cooper, a colonial-era preacher from Boston whose sermon on January 23rd, 1736 was aptly titled “A Winter Sermon.” From the wooden chancel of the Brattle Street Church in Cambridge, Rev. Cooper read from the King James Bible, Psalm 147 verses 15-18: God sendeth forth His commandment upon earth, His word runneth very swiftly. He giveth snow like wool, He scattereth the frost like ashes. He casteth forth ice like morsels. Who can stand before this cold? God sendeth out His word, and melteth them, He causeth the wind to blow, and the waters flow. And then, in beautiful 18th century discourse, Rev. Cooper argues that the cold is a very powerful means of spiritual practice and devotion. He also lifts up the need for greater service to one another, both neighbor and stranger, due to the many hardships of this season. -

David A. Gemmell's First Novellegend, a Powerful Heroic Fantasy, Was Published in 1984

Generated by ABC Amber LIT Converter, http://www.processtext.com/abclit.html David A. Gemmell's first novelLegend, a powerful heroic fantasy, was published in 1984. Since then he has become a full-time writer and his bestsellers include the Jon Shannow novels,Wolf in Shadow, The Last Guardian andBloodstone, the continuingDrenai series, andThe First Chronicles of Druss the Legend. His most recent bestsellers,Sword in the Storm, Echoes of the Great Song andMidnight Falcon, are also published by Corgi. David Gemmell is married with two teenage children and lives in East Sussex. By David Gemmell The Drenai books Legend The King Beyond the Gate Waylander Quest for Lost Heroes Waylander 2: In the Realm of the Wolf The First Chronicles of Druss the Legend The Legend of Deathwalker Winter Warriors Hero in the Shadows The Jon Shannow books Wolf in Shadow The Last Guardian Bloodstone The Stones of Power books Ghost King Last Sword of Power Lion of Macedon Generated by ABC Amber LIT Converter, http://www.processtext.com/abclit.html Dark Prince The Hawk Queen books Ironhand's Daughter The Hawk Eternal The Rigante books Sword in the Storm Midnight Falcon Ravenheart Individual titles Knights of Dark Renown Drenai Tales Morning Star Dark Moon Echoes of the Great Song THE LEGEND OF DEATHWALKER David A. Gemmell CORGI BOOKS THE LEGEND OF DEATHWALKER A CORGI BOOK : 0 551 14252 2 Originally published in Great Britain by Bantam Press, Generated by ABC Amber LIT Converter, http://www.processtext.com/abclit.html a division of Transworld Publishers PRINTING HISTORY Bantam Press edition published 1996 Corgi edition published 1996 7 9 10 8 6 Copyright © David Gemmell 1996 The right of David Gemmell to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

The Shanachie Volume 10

Vol. X. No.1 Connecticut Irish-American Historical Society January-February 1998 Meriden Irish immigrant killed in heroic rescue A 33-year-old native of "He had not time to County Galway died a save himself," reported hero's death in Meriden the Meriden Morning on Jan. 4, 1909. Record, "for the locomo Michael Donlon was tive bore down upon him, killed when he stepped in striking him at the back of front of a railroad engine the head and hurling his to push a mother and her body to one side. Mrs. young daughter out of the Gauthier suffered only a path of the oncoming shock from the accident, train. having fallen one side of An employee in the the rails and her daughter baggage room at .the Meri the other side." den train station, Donlon Donlon was taken by was hauling an empty cart ambulance to the city toward the north end of hospital and treated by the depot to pick up lug Dr. Lockwood. The in gage and parcels from the jured Irishman was bleed 2:12 p.m. express when he saw tripped. Her mother, a Mrs. Gau ing profusely from a large gash at several women with a young girl and thier, had gone back to assist her, the base of his skull, but his body a baby in a carriage attempting to but was terror stricken as she saw was not bruised or injured in any cross the tracks to Colony Street the train approaching. way. He died around midnight ahead of the train. -

John Smith Hummingbird

John Smith Hummingbird John Smith – Guitars, Vocals, Keys Cara Dillon – Vocals John McCusker – Fiddle, Whistles Ben Nicholls – Double Bass, Fender P-Bass Sam Lakeman – Shakers Strings on Boudica Jon Thorne – Double Bass Rachael Lander – Cello Kirsty Mangan – Violin, Viola Produced by Sam Lakeman Recorded at Random Sounds, Somerset, March 2018 Mixed by Mike ‘Spike’ Drake and Sam Lakeman Mastered by Tim Young at Metropolis Enormous thanks to my team: David Macias and Sara Silver at Thirty Tigers, Michelle Conceison and Neil Pearson at Market Monkeys, Chris Meehan and Simon Pursehouse at Sentric and Paul Spraggon at SSB. Thanks also to Cecile Communal and Amanda Chiu. Tremendous gratitude to Sam, Cara, Ben, John, Rachael, Kirsty, Jon, Spike and Tim for their remarkable generosity and light touch. Manager – Michelle Conceison, Market Monkeys Agent – Matt Hanner, ATC Live All songs published by Sentric Music Ltd except The Time Has Come (Heathside Music Ltd / Logo Songs Ltd) Bird by Tony Millionaire / maakies.com Design by Oliver Smith / smiths.studio Portraits by Rose Cousins / rosecousins.com This is a Commoner Records release, brought to you via Thirty Tigers Worldwide. johnsmithjohnsmith.com Hummingbird So, gone before we made one year Lowlands Of Holland John Smith Like all good things she passed Trad Arr. Smith DADGAD She disappeared into the breeze DADGAD And flew out for the last When I met her she was just engaged The night that we were married and laid upon our bed I was only twenty-three In these times of constant change A man came -

Swami Vivekananda Complete Works Volume 8

Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 8 Lectures and Discourses Writings: Prose Writings: Poems Notes of Class Talks and Lectures Sayings and Utterances Epistles - Fourth Series Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 8 Lectures and Discourses Discourses on Jnana-Yoga Six Lessons on Raja-Yoga Women of India My Life and Mission Buddha's Message to the World Discipleship Is Vedanta the Future Religion? Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 8 Lectures and Discourses Discourses on Jnana-Yoga I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 8 Lectures and Discourses Six Lessons on Raja-Yoga I II III IV V VI Home / Complete-Works / Volume 8 / Lectures and Discourses / << WOMEN OF INDIA (Delivered at the Shakespeare Club House, in Pasadena, California, on January 18, 1900) SWAMI VIVEKANANDA: "Some persons desire to ask questions about Hindu Philosophy before the lecture and to question in general about India after the lecture; but the chief difficulty is I do not know what I am to lecture on. I would be very glad to lecture on any subject, either on Hindu Philosophy or on anything concerning the race, its history, or its literature. If you, ladies and gentlemen, will suggest anything, I would be very glad." QUESTIONER: "I would like to ask, Swami, what special principle in Hindu Philosophy you would have us Americans, who are a very practical people, adopt, and what that would do for us beyond what Christianity can do." SWAMI VIVEKANANDA: "That is very difficult for me to decide; it rests upon you. -

Interview with Judy, Emma Tobin, UNC-CH – Photo-Journalism And

“Things that simply won’t let go” Photographs by Emma Tobin Judy Hogan is an 81-year-old environmental activist, writer, and teacher. Over the past few decades, she has fought a myriad of different environmental justice issues affecting her community in Chatham County, N.C. Right now, she is leading an effort against Duke Energy dumping and incinerating coal ash in her town. She publishes books and poetry and teaches writing classes twice a week. This series is accompanied by selected poems from Hogan’s most recently published book, called “Shadows”, which is autobiographical about her daily life. I took a more free-form, artistic approach with this caption style because I want Judy Hogan to speak for herself. One: "For me it’s shadows. Every day I walk across the dam, I watch for my shadow marching below me, down the hill, and some days, when the wind is still, even across the water and up the hill at the other end of the earthen dam that creates Jordan Lake. In the painting there is one small human figure surrounded by rushing water, darkly threatening clouds, with only a small window of blue that could be sky but is probably water. That little shadow is very persistent as she trudges along. Even in a wind, she doesn’t hesitate, pulls her hood up to protect her neck and ears. A step at a time a great distance can prove possible. But, oh for the courage to believe in that shadow. I like to think that when I’m gone, and even if storm clouds dominate, and water boils and foams, and wind is cruel and relentless, that my shadow– all that is left of me and whatever words on paper survive my death–will keep on walking with firm steps, seeing more than I can see now, accepting storms, even lightning, but refusing to be dismissed, ignored, or turned aside–something eternal or stubborn, or so part of the nature of things that it simply won’t let go." - From Judy Hogan's original poem book "Shadows" Two: "How to tell it? I have a new friend in the midst of my aging, when new friends are rare. -

Chapter One, I Will Give a Brief Introduction to the Two Plays Nue And

Zeami’s Treatment of Original Source Materials in Two Plays of His Late Period: The Examples of the Nō Plays Nue and Kinuta Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yaohui Ni, B.A. Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Thesis Committee: Professor Shelley Fenno Quinn, Advisor Professor Naomi Fukumori Professor Charles J. Quinn Copyright by Yaohui Ni 2010 Abstract Zeami Motokiyo 世阿弥元清(1363?—1443?), a famous actor, playwright, and theorist of Nō drama in medieval Japan, is universally acknowledged as one of the major figures in the history of Nō. He not only composed a large body of Nō plays, but also left twenty-one critical treatises that cover a wide range of discussions from performance to the philosophy and aesthetics of Nō. In this thesis, I will discuss Zeami’s treatment of source materials in two of his exemplary plays from late in his career, Nue 鵺 and Kinuta 砧. Nue mainly describes the miserable predicament of a nue—a monster with the head of an ape, the tail of a serpent and the limbs of a tiger--who is killed by a famous warrior, Minamoto no Yorimasa 源頼政 (1104-1180). Kinuta is a story about the wife of a provincial member of the warrior class who yearns for her husband far away. Based on my analysis of honzetsu 本説 (original source materials; modern Japanese honsetsu), I will argue that beyond allusions to traditional literary works, Zeami also invokes Buddhist philosophy and ritual to make alterations in received interpretations and reception of source materials belonging to the literary tradition. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Visible Translator: Language and Identity in Meiji-period Japanese Travel Narratives Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/29r779z9 Author Shaughnessy, Orna Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Visible Translator: Language and Identity in Meiji-period Japanese Travel Narratives By Orna Elizabeth Shaughnessy A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Alan Tansman, chair Associate Professor Dan O’Neill Professor Dorothy Hale Spring 2015 Abstract The Visible Translator: Language and Identity in Meiji-period Japanese Travel Narratives by Orna Elizabeth Shaughnessy Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language University of California, Berkeley Professor Alan Tansman, chair In this dissertation I argue that the literary imagination of late nineteenth century Japanese travel narratives fixated on the figure of the translator as a model of success and mastery in the international forum who could bridge linguistic differences with aplomb. The figure of the translator during what I call ‘the moment of the translator’ from roughly the 1850s through the 1870s served a key purpose: he embodied a model of modern Japanese identity that could successfully move through international contexts, on Western terms, by means of his fluency in foreign languages. In chapter 1 I examine the multitude of historical figures who acted as translators in the late nineteenth century to argue that the cumulative force of their public stories created 'the moment of the translator.' In chapter 2 I consider one of the most popular fictional travel narratives to feature a translator figure: Kanagaki Robun's Seiyôdôchû hizakurige. -

Media Manager, Mediator, Mentor & Maker

2/27/2015 Media Manager, Mediator, Mentor & Maker 4 Key Roles for Educators in the Multi- Screen, Multi-Touch Digital Age Tennessee Child Care Resource & Referral Network Chip Donohue, PhD Amanda Armstrong, M.S. TEC Center at Erikson Institute @chipdono @AArmstrong_CD @TEC_Center #TechEarlyYears To review – What do educators need? Digital media literacy = Attitudes, knowledge, experience, competency, fluency Child development, DAP, Family and Culture 3Cs of digital media – Content Context Child 4Ms of digital leadership – Manager Mediator Mentor Maker 5Es of technology integration – Exchange Enrich Enhance Extend Empower Pre-service, In-service, Professional development Hands-on play time and tech playgroups– “use tech to learn how to use tech” Research about effective practices Effective, appropriate and intentional use with young children, parents and families Connected learning 1 2/27/2015 21st century educator = 21st century learner What types of 21st century tools do you use to build your professional growth and learning network? Being a 21st century learner matters • Learn everywhere-all-the-time • Let the digital experts teach you • Lifelong and lifewide • Formal and informal • Personal and professional • Social and connected • Digital media literacy Learning that is…active, relevant, real-world, effective, hands-on, networked, inquiry-based, innovative, personal, transformative 2 2/27/2015 Lifelong and lifewide learning ecology • Learn with anyone, anytime, anywhere, on any device • Blend formal and informal learning -

Communicating Sustainability with Visuals

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2015 Communicating Sustainability with Visuals: Issue Perception and Issue Engagement Zeynep Melis Altinay Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Altinay, Zeynep Melis, "Communicating Sustainability with Visuals: Issue Perception and Issue Engagement" (2015). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3410. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3410 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. COMMUNICATING SUSTAINABILITY WITH VISUALS: ISSUE PERCEPTION AND ISSUE ENGAGEMENT A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Manship School of Mass Communication by Zeynep M. Altinay B.A., Binghamton University, 2007 M.A., Indiana University, 2010 M.S., Indiana University , 2010 May 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my PhD advisors, Dr. Amy Reynolds, Dr. Meghan Sanders, and Dr. Margaret Reams for their excellent guidance, care, and patience. I would also like to thank Dr. Andrew Sluyter for his willingness to participate in my final defense committee and for his insightful feedback regarding my research. I will forever be thankful to my longtime advisor Amy Reynolds. She was one of the first people to welcome me to graduate school, and now eight years later, that same person will hood me at LSU’s commencement ceremony. -

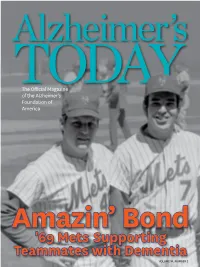

'69 Mets Supporting Teammates with Dementia

Alzheimer’s The Official Magazine TODAYof the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America Amazin’ Bond '69Mets Supporting Teammates withDementia VOLUME 14, NUMBER 3 MISSION: TO PROVIDE SUPPORT, SERVICES AND EDUCATION TO INDIVIDUALS, FAMILIES AND CAREGIVERS AFFECTED BY ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE AND RELATED DEMENTIAS NATIONWIDE, AND FUND RESEARCH FOR BETTER TREATMENT AND A CURE. Congratulations! FEATURES Teens for Alzheimer’s Awareness Scholarship Essay Contest Winners A Record-Breaking 36 Winners Received Nearly $35,000 in Scholarships! A big THANK YOU to all our participants for sharing your stories. PAGE 4 PAGE 6 PAGE 8 Hello Out There, I Have Dementia Amazin’ Bond: ’69 Miracle Mets Join the Movement: Opening UP Supporting Teammates with Dementia Communication with Dance/ Movement Therapy PAGE 16 PAGE 19 PAGE 22 What Alzheimer’s Taught Me: Simple Act, Potentially Big Impact What Families Should Know: Teens Share Their Stories Planning for Long-term Care Chairman of the Board The content of this magazine is not intended to be a Bert E. Brodsky substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of a physician Board of Trustees or other qualified health provider with any questions Gerald (Jerry) Angowitz, Esq. you may have regarding a medical condition. Barry Berg, CPA Never disregard professional medical advice or Luisa Echevarria Publisher delay in seeking it because of something you have Steve Israel Alzheimer’s Foundation of America read in this magazine. The Alzheimer’s Foundation Arthur Laitman, Esq. of America makes no representations as to the Edward D. Miller Editors accuracy, completeness, suitability or validity of Chris Schneider any of the content included in this magazine, which Associate Board Members Karen Mazzotta is provided on an “as is” basis.