Swami Vivekananda Complete Works Volume 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo Ghosh

UNIT 6 HINDUISM : SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND SRI AUROBINDO GHOSH Structure 6.2 Renaissance of Hi~~duis~iiand the Role of Sri Raniakrishna Mission 0.3 Swami ViveItananda's Philosopliy of Neo-Vedanta 6.4 Swami Vivckanalida on Nationalism 6.4.1 S\varni Vivcknnnnda on Dcrnocracy 6.4.2 Swami Vivckanar~daon Social Changc 6.5 Transition of Hinduism: Frolii Vivekananda to Sri Aurobindo 6.5. Sri Aurobindo on Renaissance of Hinduism 6.2 Sri Aurol>i~ldoon Evil EffLrcls of British Rulc 6.6 S1.i Aurobindo's Critique of Political Moderates in India 6.6.1 Sri Aurobilido on the Essencc of Politics 6.6.2 SI-iAurobindo oil Nationalism 0.6.3 Sri Aurobindo on Passivc Resistance 6.6.4 Thcory of Passive Resistance 6.6.5 Mcthods of Passive Rcsistancc 6.7 Sri Aurobindo 011 the Indian Theory of State 6.7.1 .J'olitical ldcas of Sri Aurobindo - A Critical Study 6.8 Summary 1 h 'i 6.9 Exercises j i 6.1 INTRODUCTION In 19"' celitury, India camc under the British rule. Due to the spread of moder~ieducation and growing public activities, there developed social awakening in India. The religion of Hindus wns very harshly criticized by the Christian n?issionaries and the British historians but at ~hcsanie timc, researches carried out by the Orientalist scholars revealcd to the world, lhc glorioi~s'tiaadition of the Hindu religion. The Hindus responded to this by initiating reforms in thcir religion and by esfablishing new pub'lie associations to spread their ideas of refor111 and social development anlong the people. -

SWAMI VIVEKANANDA's SPEECH at WORLD PARLIAMENT of RELIGION, CHICAGO RESPONSE to WELCOME Sisters and Brothers of America, It F

SWAMI VIVEKANANDA’S SPEECH AT WORLD PARLIAMENT OF RELIGION, CHICAGO RESPONSE TO WELCOME Sisters and Brothers of America, It fills my heart with joy unspeakable to rise in response to the warm and cordial welcome which you have given us. I thank you in the name of the most ancient order of monks in the world; I thank you in the name of the mother of religions; and I thank you in the name of millions and millions of Hindu people of all classes and sects. My thanks, also, to some of the speakers on this platform who, referring to the delegates from the Orient, have told you that these men from far-off nations may well claim the honour of bearing to different lands the idea of toleration. I am proud to belong to a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance. We believe not only in universal toleration, but we accept all religions as true. I am proud to belong to a nation which has sheltered the persecuted and the refugees of all religions and all nations of the earth. I am proud to tell you that we have gathered in our bosom the purest remnant of the Israelites, who came to Southern India and took refuge with us in the very year in which their holy temple was shattered to pieces by Roman tyranny. I am proud to belong to the religion which has sheltered and is still fostering remnant Zoroastrian nation. I will quote to you, brethren, a few lines from a hymn which I remember to have repeated from my earliest boyhood, which is every day repeated by millions of human beings: "As the different streams having their -

Swami Vivekananda

Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 9 Letters (Fifth Series) Lectures and Discourses Notes of Lectures and Classes Writings: Prose and Poems (Original and Translated) Conversations and Interviews Excerpts from Sister Nivedita's Book Sayings and Utterances Newspaper Reports Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 9 Letters - Fifth Series I Sir II Sir III Sir IV Balaram Babu V Tulsiram VI Sharat VII Mother VIII Mother IX Mother X Mother XI Mother XII Mother XIII Mother XIV Mother XV Mother XVI Mother XVII Mother XVIII Mother XIX Mother XX Mother XXI Mother XXII Mother XXIII Mother XXIV Mother XXV Mother XXVI Mother XXVII Mother XXVIII Mother XXIX Mother XXX Mother XXXI Mother XXXII Mother XXXIII Mother XXXIV Mother XXXV Mother XXXVI Mother XXXVII Mother XXXVIII Mother XXXIX Mother XL Mrs. Bull XLI Miss Thursby XLII Mother XLIII Mother XLIV Mother XLV Mother XLVI Mother XLVII Miss Thursby XLVIII Adhyapakji XLIX Mother L Mother LI Mother LII Mother LIII Mother LIV Mother LV Friend LVI Mother LVII Mother LVIII Sir LIX Mother LX Doctor LXI Mother— LXII Mother— LXIII Mother LXIV Mother— LXV Mother LXVI Mother— LXVII Friend LXVIII Mrs. G. W. Hale LXIX Christina LXX Mother— LXXI Sister Christine LXXII Isabelle McKindley LXXIII Christina LXXIV Christina LXXV Christina LXXVI Your Highness LXXVII Sir— LXXVIII Christina— LXXIX Mrs. Ole Bull LXXX Sir LXXXI Mrs. Bull LXXXII Mrs. Funkey LXXXIII Mrs. Bull LXXXIV Christina LXXXV Mrs. Bull— LXXXVI Miss Thursby LXXXVII Friend LXXXVIII Christina LXXXIX Mrs. Funkey XC Christina XCI Christina XCII Mrs. Bull— XCIII Sir XCIV Mrs. Bull— XCV Mother— XCVI Sir XCVII Mrs. -

Aspects of Indian Modernity: a Personal Perspective

ASPECTS OF INDIAN MODERNITY: A PERSONAL PERSPECTIVE MOHAN RAMANAN University of Hyderabad, India [email protected] 75 I There are two Indias. One is called Bharat, after a legendary King. This represents a traditional culture strongly rooted in religion. The other is India, the creation of a modern set of circumstances. It has to do with British rule and the modernities set in motion by that phenomenon. India as a nation is very much a creation of the encounter between an ancient people and a western discourse. The British unified the geographical space we call India in a manner never done before. Only Asoka the Great and Akbar the Great had brought large parts of the Indian sub- continent under their control, but their empires were not as potent or as organized as the British Empire. The British gave India communications, railways, the telegraph and telephones; they organized their knowledge of India systematically by surveying the landscape, categorizing the flora and fauna and by dividing the population into castes and religious groupings. Edward Said has shown in his well- known general studies of the colonial enterprise how this accumulation of knowledge is a way of establishing power. In India the British engaged themselves in this knowledge accumulation to give themselves an Empire and a free market and a site to work their experiments in social engineering. This command of the land also translated into command of the languages of the people. British scholars like G.U. Pope and C.P. Brown, to name only two, miscelánea: a journal of english and american studies 34 (2006): pp. -

Tantra Yoga Secrets (385)

A Tantra Yoga Workshop from a Master Teacher Tantra Yoga Secrets empowers readers to overcome emotions, gain new knowledge, and live a more fulfilling spiritual lifestyle. "Takes one beyond the illusionary misunderstanding that tantric practice/sadhana is about sexuality and raises it to its full value as a powerful way to wake up to the Self of all." -GABRIEL COUSENS, MD, DD, diplomat of Ayurveda, acknowledged Kundalini and Shaktipat master; author of Conscious Eating and Rainbow Green Live-Food Cuisine Considered to be the highest and most rapid path to enlightenment, Tantra Yoga is a practice of transformational self-healing. While many are drawn to Tantra on the promise of an enhanced sexual practice-longer orgasms, increased stamina-the real Tantra aims to awaken Kundalini, the dormant potential force in the human personality. Master teacher and author Mukunda Stiles invites readers to participate in a tradition that includes a vast range of practical teachings that lead to the expansion of human consciousness and the awakening of a primal energy. Stiles explains this incredibly intimate and life-changing practice with grace, structure, and clarity. "These lessons provide a system of practices that con open doors into rewording perceptions of reality." -ROBERT SVOBODA, B.A.M.S., ayurvedic physician, author of Aghora; Ayurveda: Life, Health, and Longevity; Prakruti: Your Ayurvedic Constitution; and Ayurveda for Women "Anyone seeking self-awareness will benefit by following the step-by-step asana and meditation practices from this ancient path." -MA JAYA SAT! BHAGAVATI, Kashi Ashram, founder of Kali Natha Yoga "Tantra Yoga Secrets is an invaluable manual for students ready to progress beyond yoga postures to expanded states of awareness." -LINDA JOHNSEN, author of Daughters of the Goddess: The Women Saints of India "Tantra Yoga Secrets provides an insightful view of this fascinating yet misunderstood topic of how to bolance the male and female energies of Shiva and Shakti within us to achieve swastha (the harmony of health with the inner Selij." -DR. -

The Neo-Vedanta Philosophy of Swami Vivekananda

VEDA’S JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE (JOELL) Vol.6 Issue 4 An International Peer Reviewed (Refereed) Journal 2019 Impact Factor (SJIF) 4.092 http://www.joell.in RESEARCH ARTICLE THE NEO-VEDANTA PHILOSOPHY OF SWAMI VIVEKANANDA Tania Baloria (Ph.D Research Scholar, Jaipur National University, Jagatpura, Jaipur.) doi: https://doi.org/10.33329/joell.64.19.108 ABSTRACT This paper aims to evaluate the interpretation of Swami Vivekananda‘s Neo-Vedanta philosophy.Vedanta is the philosophy of Vedas, those Indian scriptures which are the most ancient religious writings now known to the world. It is the philosophy of the self. And the self is unchangeable. It cannot be called old self and new self because it is changeless and ultimate. So the theory is also changeless. Neo- Vedanta is just like the traditional Vedanta interpreted with the perspective of modern man and applied in practical-life. By the Neo-Vedanta of Swami Vivekananda is meant the New-Vedanta as distinguished from the old traditional Vedanta developed by Sankaracharya (c.788 820AD). Neo-Vedantism is a re- establishment and reinterpretation Of the Advaita Vedanta of Sankara with modern arguments, in modern language, suited to modern man, adjusting it with all the modern challenges. In the later nineteenth century and early twentieth century many masters used Vedanta philosophy for human welfare. Some of them were Rajarammohan Roy, Swami DayanandaSaraswati, Sri CattampiSwamikal, Sri Narayana Guru, Rabindranath Tagore, Mahatma Gandhi, Sri Aurobindo, and Ramana Maharsi. Keywords: Female subjugation, Religious belief, Liberation, Chastity, Self-sacrifice. Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Copyright © 2019 VEDA Publications Author(s) agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License . -

Sri Ramakrishna & His Disciples in Orissa

Preface Pilgrimage places like Varanasi, Prayag, Haridwar and Vrindavan have always got prominent place in any pilgrimage of the devotees and its importance is well known. Many mythological stories are associated to these places. Though Orissa had many temples, historical places and natural scenic beauty spot, but it did not get so much prominence. This may be due to the lack of connectivity. Buddhism and Jainism flourished there followed by Shaivaism and Vainavism. After reading the lives of Sri Chaitanya, Sri Ramakrishna, Holy Mother and direct disciples we come to know the importance and spiritual significance of these places. Holy Mother and many disciples of Sri Ramakrishna had great time in Orissa. Many are blessed here by the vision of Lord Jagannath or the Master. The lives of these great souls had shown us a way to visit these places with spiritual consciousness and devotion. Unless we read the life of Sri Chaitanya we will not understand the life of Sri Ramakrishna properly. Similarly unless we study the chapter in the lives of these great souls in Orissa we will not be able to understand and appreciate the significance of these places. If we go on pilgrimage to Orissa with same spirit and devotion as shown by these great souls, we are sure to be benefited spiritually. This collection will put the light on the Orissa chapter in the lives of these great souls and will inspire the devotees to read more about their lives in details. This will also help the devotees to go to pilgrimage in Orissa and strengthen their devotion. -

Expand Your Heart – Vkjuly19

1 TheVedanta Kesari July 2019 1 The Vedanta Kesari The Vedanta Cover Story page 11... 1 A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly `15 July of the Ramakrishna Order since 1914 2019 TheTheVedanta Kesari Sri Ramakrishna Math, Mylapore, Chennai 600 004 h(044) 2462 1110 E-mail: [email protected] Website : www.chennaimath.org DearDea Readers, TThe Vedanta Kesari is one of the oldest cultural aandnd sspiritual magazines in the country. Started under tthehe gguidance and support of Swami Vivekananda, the ffirstirs issue of the magazine, then called BBrahmavadinr , came out on 14 Sept 1895. July 2019 BrBrahmavadin was run by one of Swamiji’s ardent ffollowersol Sri Alasinga Perumal. After his death in 4 1190990 the magazine publication became irregular, aandnd stoppeds in 1914 whereupon the Ramakrishna OOrder revived it as The Vedanta Kesari. Swami Vivekananda’s concern for the mmagazine is seen in his letters to Alasinga Perumal whwheree he writes: ‘Now I am bent upon starting the journal.’ ‘Herewith I send a hundred dollars…. Hope this will go just a little in starting your The Vedanta Kesari The Vedanta paper.’ ‘I am determined to see the paper succeed.’ ‘The Song of the Sannyasin is my first contribution for your journal.’ ‘I learnt from your letter the bad financial state that Brahmavadin is in.’ ‘It must be supported by the Hindus if they have any sense of virtue or gratitude left in them.’ ‘I pledge myself to maintain the paper anyhow.’ ‘The Brahmavadin is a jewel—it must not perish. Of course, such a paper has to be kept up by private help always, and we will do it.’ For the last 105 years, without missing a single issue, the magazine has been carrying the invigorating message of Vedanta with articles on spirituality, culture, philosophy, youth, personality development, science, holistic living, family and corporate values. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Shraddha's Book

1 The Beautiful Lady of my dream 2 A Danda Swami’s Tribute conveyed to the author by Swami Mangalananda Giri Something interesting happened that you will appreciate. An 84-year-old Danda Swami is staying at the ashram during the rains. He speaks very good English and frequently comes to my room. He asked for any book about Ma, and I told him to browse my “library” which now extends the full length of one wall. Without any prompting from me, he went directly to your book “In Her Perfect Love”, and I gladly lent it to him. After a day he came back and was literally raving about the book. He said, ‘If I sold everything in the world, it would not pay the price of this book. I’ve been mad for this book since I started it - reading it day and night.’ I told him I communicated with you and would pass on his enthusiasm. Swami Mangalananda Contents Introduction………………………………………… 4 Acknowledgement………………………………….. 6 Swamiji’s Blessing…………………………… 7 Foreword ............................................... ...................... 8 First Darshan(1960) ........................................................10 First Trip (November 6, 1970-November 20, 1970) Suktal ................................................................ 14 Kanpur ............................................................... .17 Second Trip (May 9, 1971-May 30, 1971) Varanasi ............................................................. .23 Vrindavan ............................................................ 28 Delhi .................................................................. -

Thevedanta Kesari February 2020

1 TheVedanta Kesari February 2020 1 The Vedanta Kesari The Vedanta Cover Story Sri Ramakrishna : A Divine Incarnation page 11 A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly 1 `15 February of the Ramakrishna Order since 1914 2020 2 Mylapore Rangoli competition To preserve and promote cultural heritage, the Mylapore Festival conducts the Kolam contest every year on the streets adjoining Kapaleswarar Temple near Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai. Regd. Off. & Fact. : Plot No.88 & 89, Phase - II, Sipcot Industrial Complex, Ranipet - 632 403, Tamil Nadu. Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Phone : 04172 - 244820, 651507, PRIVATE LIMITED Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Tele Fax : 04172 - 244820 (Manufacturers of Active Pharmaceutical Printed by B. Rajkumar, Chennai - 600 014 on behalf of Sri Ramakrishna Math Trust, Chennai - 600 004 and Ingredients and Intermediates) E-mail : [email protected] Web Site : www.svisslabss.net Printed at M/s. Rasi Graphics Pvt. Limited, No.40, Peters Road, Royapettah, Chennai - 600014. Website: www.chennaimath.org E-mail: [email protected] Ph: 6374213070 3 THE VEDANTA KESARI A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly of The Ramakrishna Order Vol. 107, No. 2 ISSN 0042-2983 107th YEAR OF PUBLICATION CONTENTS FEBRUARY 2020 ory St er ov C 11 Sri Ramakrishna: A Divine Incarnation Swami Tapasyananda 46 20 Women Saints of FEATURES Vivekananda Varkari Tradition Rock Memorial Atmarpanastuti Arpana Ghosh 8 9 Yugavani 10 Editorial Sri Ramakrishna and the A Curious Boy 18 Reminiscences Pilgrimage Mindset 27 Vivekananda Way Gitanjali Murari Swami Chidekananda 36 Special Report 51 Pariprasna Po 53 The Order on the March ck et T a le 41 25 s Sri Ramakrishna Vijayam – Poorva: Magic, Miracles Touching 100 Years and the Mystical Twelve Lakshmi Devnath t or ep R l ia c e 34 31 p S Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Printed by B. -

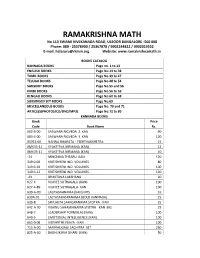

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL.