UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nihonbashi: Edo's Contested Center Marcia Yonemoto

, East Asian History NUMBERS 17/18· JUNE/DECEMBER 1999 Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University 1 Editor Geremie R. Barme Assistant Editor Helen Lo Editorial Board Mark Elvin (Convenor) John Clark Andrew Fraser Helen Hardacre Colin Jeffcott W. ]. F. Jenner Lo Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Design and Production Helen Lo Business Manager Marion Weeks Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This double issue of East Asian History, 17/18, was printed in FebrualY 2000. Contributions to The Editor, East Asian History Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Phone +61 26249 3140 Fax +61 26249 5525 email [email protected] Subscription Enquiries to Subscriptions, East Asian History, at the above address Annual Subscription Australia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Whose Strange Stories? P'u Sung-ling (1640-1715), Herbert Giles (1845- 1935), and the Liao-chai chih-yi John Minford and To ng Man 49 Nihonbashi: Edo's Contested Center Marcia Yonemoto 71 Was Toregene Qatun Ogodei's "Sixth Empress"? 1. de Rachewiltz 77 Photography and Portraiture in Nineteenth-Century China Regine Thiriez 103 Sapajou Richard Rigby 131 Overcoming Risk: a Chinese Mining Company during the Nanjing Decade Ti m Wright 169 Garden and Museum: Shadows of Memory at Peking University Vera Schwarcz iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing M.c�J�n, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover illustration Talisman-"Passport for wandering souls on the way to Hades," from Henri Dore, Researches into Chinese superstitions (Shanghai: T'usewei Printing Press, 1914-38) NIHONBASHI: EDO'S CONTESTED CENTER � Marcia Yonemoto As the Tokugawa 11&)II regime consolidated its military and political conquest Izushi [Pictorial sources from the Edo period] of Japan around the turn of the seventeenth century, it began the enormous (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo, 1975), vol.4; project of remaking Edo rI p as its capital city. -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

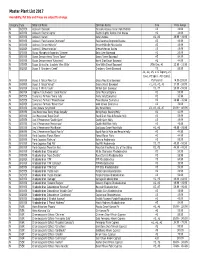

Master Plant List 2017.Xlsx

Master Plant List 2017 Availability, Pot Size and Prices are subject to change. Category Type Botanical Name Common Name Size Price Range N BREVER Azalea X 'Cascade' Cascade Azalea (Glenn Dale Hybrid) #3 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Electric Lights' Electric Lights Double Pink Azalea #2 44.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Karen' Karen Azalea #2, #3 39.99 - 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Poukhanense Improved' Poukhanense Improved Azalea #3 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Renee Michelle' Renee Michelle Pink Azalea #3 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Stewartstonian' Stewartstonian Azalea #3 49.99 N BREVER Buxus Microphylla Japonica "Gregem' Baby Gem Boxwood #2 29.99 N BREVER Buxus Sempervirens 'Green Tower' Green Tower Boxwood #5 64.99 N BREVER Buxus Sempervirens 'Katerberg' North Star Dwarf Boxwood #2 44.99 N BREVER Buxus Sinica Var. Insularis 'Wee Willie' Wee Willie Dwarf Boxwood Little One, #1 13.99 - 21.99 N BREVER Buxus X 'Cranberry Creek' Cranberry Creek Boxwood #3 89.99 #1, #2, #5, #15 Topiary, #5 Cone, #5 Spiral, #10 Spiral, N BREVER Buxus X 'Green Mountain' Green Mountain Boxwood #5 Pyramid 14.99-299.99 N BREVER Buxus X 'Green Velvet' Green Velvet Boxwood #1, #2, #3, #5 17.99 - 59.99 N BREVER Buxus X 'Winter Gem' Winter Gem Boxwood #5, #7 59.99 - 99.99 N BREVER Daphne X Burkwoodii 'Carol Mackie' Carol Mackie Daphne #2 59.99 N BREVER Euonymus Fortunei 'Ivory Jade' Ivory Jade Euonymus #2 35.99 N BREVER Euonymus Fortunei 'Moonshadow' Moonshadow Euonymus #2 29.99 - 35.99 N BREVER Euonymus Fortunei 'Rosemrtwo' Gold Splash Euonymus #2 39.99 N BREVER Ilex Crenata 'Sky Pencil' -

Theory of Robot Communication: I

Hoorn, J. F. (2018). Theory of robot communication: I. The medium is the communication partner. arXiv:cs, 2502565(v1), 1-21. 1 Theory of Robot Communication: I. The Medium is the Communication Partner Johan F. Hoorn1,2 1 Department of Computing and School of Design, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, 999077, Hong Kong. 2 Department of Communication Science, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 1081 HV, The Netherlands. Correspondence should be addressed to Johan F. Hoorn; [email protected] Abstract When people use electronic media for their communication, Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) theories describe the social and communicative aspects of people’s interpersonal transactions. When people interact via a remote-controlled robot, many of the CMC theses hold. Yet, what if people communicate with a conversation robot that is (partly) autonomous? Do the same theories apply? This paper discusses CMC theories in confrontation with observations and research data gained from human-robot communication. As a result, I argue for an addition to CMC theorizing when the robot as a medium itself becomes the communication partner. In view of the rise of social robots in coming years, I define the theoretical precepts of a possible next step in CMC, which I elaborate in a second paper. Introduction Currently, the development and application of social robots in real-life settings rapidly increases. Whereas robots initially were the domain of science-fiction, today, social robots are tried out in service-oriented professions in healthcare, education, and commerce (Broadbent, 2017). Habitually, general-purpose robots are readied for a particular task in a particular environment such as guidance through an exhibition or reception in a hotel (Broadbent, 2017). -

SBS Chill 12:00 AM Monday, 23 March 2020 Start Title Artist 00:07 Sealed Air Ghosts of Paraguay

SBS Chill 12:00 AM Monday, 23 March 2020 Start Title Artist 00:07 Sealed Air Ghosts of Paraguay 03:00 Tíbrá Samaris 06:23 Fanfare Of Life Leftfield 12:35 Halving the Compass (Rhian Sheehan Remix) Helios 19:08 Plastic Heart Jens Buchert 24:49 Run Air 28:48 Swiss (Orginal Mix) Deeb 33:04 Soul Bird (Tin Tin Deo) Cal Tjader 35:46 The Garden A.J. Heath 40:32 Sundown Living Room 45:27 When're You Gonna Break My Heart Silver Ray 58:18 Song 1 DJ Krush 63:42 Endless Summer Flanger Powergold Music Scheduling Licensed to SBS SBS Chill 1:00 AM Monday, 23 March 2020 Start Title Artist 00:08 Babies Colleen 03:34 Traces Of You Anoushka Shankar & Nora... 07:20 They have escaped the weight of darkness Olafur Arnalds 11:28 Telco Daniel Lanois 15:02 Grey Skies Ben Westbeech 16:52 Hold On Gary B 23:36 (Exchange) Massive Attack 27:47 Interview With The Angel Ghostland 32:14 Finally Moving Pretty Lights 36:44 Agua José Padilla 43:53 Tomorrow Island (yesterday mix) Frank Borell 49:04 Leaves Winterbourne 54:39 Already Replaced Steve Hauschildt 58:43 Jets Bonobo Powergold Music Scheduling Licensed to SBS SBS Chill 2:00 AM Monday, 23 March 2020 Start Title Artist 00:05 Riverside Agnes Obel 03:53 Desert (Version Française) Emile Simon 06:51 Ghost Song Spacecadet Lullabies 14:54 War Song Phamie Gow 18:01 Natural Cause Emancipator 23:06 Siren Of The Sun Urban Myth Club 28:33 Sand Max Melvin 34:37 Mamma Africa Babylon Syndicate 39:29 The Dust of Months Bill Wells 43:38 Memory (Red Scarf) V.K 46:35 The Dove Caspian 49:40 1+1 La Chambre 56:36 Mir Murcof 63:11 Metro Francois -

Social Decorating: Dutch Salons in Early Modern Japan

SOCIAL DECORATING: DUTCH SALONS IN EARLY MODERN JAPAN TERRENCE JACKSON Adrian College Seated Intellect, Performative Intellect Cultural salons proliferated during the last half of the eighteenth century in Japan, accommodating a growing interest in the za arts and literature (za-bungei 座文芸). The literal meaning of za 座 was “seat,” and the za arts (visual and literary) were performed within groups, which were presumably “seated” together. Za culture first appeared as early as the thirteenth century when the Emperor Go-Toba 後鳥羽 held poetry gatherings in his salon (zashiki 座敷). In practice, za also referred to the physical space where these individuals gathered, and it is from that that the related term zashiki, or “sitting room” was derived.1 Zashiki served a function similar to the salons of Europe in the early modern period—as a semi-private space to entertain guests and enjoy cultural interaction. Za arts gatherings met within the homes of participants or patrons, but also in rented zashiki at temples and teahouses. During their meetings, professionals and amateurs interacted and cooperated to produce culture. The epitome of this was renga 連歌 poetry in which groups created linked-verses. However, other types of cultural groups met in salons to design such items as woodblock prints and playful calendars, to debate flower arranging, or to discuss the latest bestsellers. Within these spaces, the emphasis was on group production and on the rights of all attendees to participate, regardless of social background. The atmosphere of zashiki gatherings combined civility, curiosity, playfulness, and camaraderie. The distinction between artistic and intellectual pursuits had fuzzy boundaries during the Tokugawa period, and scholars largely operated within a social world similar to artists, poets, and fiction writers . -

<全文>Japan Review : No.34

<全文>Japan review : No.34 journal or Japan review : Journal of the International publication title Research Center for Japanese Studies volume 34 year 2019-12 URL http://id.nii.ac.jp/1368/00007405/ 2019 PRINT EDITION: ISSN 0915-0986 ONLINE EDITION: ISSN 2434-3129 34 NUMBER 34 2019 JAPAN REVIEWJAPAN japan review J OURNAL OF CONTENTS THE I NTERNATIONAL Gerald GROEMER A Retiree’s Chat (Shin’ya meidan): The Recollections of the.\ǀND3RHW+H]XWVX7ǀVDNX R. Keller KIMBROUGH Pushing Filial Piety: The Twenty-Four Filial ExemplarsDQGDQ2VDND3XEOLVKHU¶V³%HQH¿FLDO%RRNVIRU:RPHQ´ R. Keller KIMBROUGH Translation: The Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars R 0,85$7DNDVKL ESEARCH 7KH)LOLDO3LHW\0RXQWDLQ.DQQR+DFKLUǀDQG7KH7KUHH7HDFKLQJV Ruselle MEADE Juvenile Science and the Japanese Nation: 6KǀQHQ¶HQDQGWKH&XOWLYDWLRQRI6FLHQWL¿F6XEMHFWV C ,66(<ǀNR ENTER 5HYLVLWLQJ7VXGD6ǀNLFKLLQ3RVWZDU-DSDQ³0LVXQGHUVWDQGLQJV´DQGWKH+LVWRULFDO)DFWVRIWKH.LNL 0DWWKHZ/$5.,1* 'HDWKDQGWKH3URVSHFWVRI8QL¿FDWLRQNihonga’s3RVWZDU5DSSURFKHPHQWVZLWK<ǀJD FOR &KXQ:D&+$1 J )UDFWXULQJ5HDOLWLHV6WDJLQJ%XGGKLVW$UWLQ'RPRQ.HQ¶V3KRWRERRN0XUǀML(1954) APANESE %22.5(9,(:6 COVER IMAGE: S *RVRNXLVKLNLVKLNL]X御即位式々図. TUDIES (In *RVRNXLGDLMǀVDLWDLWHQ]XDQ7DLVKǀQREX御即位大甞祭大典図案 大正之部, E\6KLPRPXUD7DPDKLUR 下村玉廣. 8QVǀGǀ © 2019 by the International Research Center for Japanese Studies. Please note that the contents of Japan Review may not be used or reproduced without the written permis- sion of the Editor, except for short quotations in scholarly publications in which quoted material is duly attributed to the author(s) and Japan Review. Japan Review Number 34, December 2019 Published by the International Research Center for Japanese Studies 3-2 Goryo Oeyama-cho, Nishikyo-ku, Kyoto 610-1192, Japan Tel. 075-335-2210 Fax 075-335-2043 Print edition: ISSN 0915-0986 Online edition: ISSN 2434-3129 japan review Journal of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies Number 34 2019 About the Journal Japan Review is a refereed journal published annually by the International Research Center for Japanese Studies since 1990. -

English:『Akita Ranga and Its International Dimensions: a Short

Institute for Asian Studies and Regional Collaboration Akita International University, Japan Contents Akita Ranga and Its International Dimensions: foreword/acknowledgements 5 A Short Tour Text, Editing, and Production: Kuniko Abe introduction 7 Design Concept: Takuto Nishida (research assistant) Published in 2018 by Akita International University what is akita ranga? 9 Institute for Asian Studies and Regional Collaboration http://web.aiu.ac.jp/iasrc/ visual wonders in the edo era and akita ranga 11 kaitaishinsho: new anatomy book 13 Published in conjunction with the exhibition "Akita Ranga and Its International Dimensions" at Nakajima pine tree and parrot by satake shozan 15 Library, Akita International University, November 8, 2017-January 12, 2018, produced by Kuniko Abe, mitsumata by odano naotake 16 associate professor, sponsored by the Institute for Asian Studies and Regional Collaboration scenery by the lake by satake shozan 19 shinobazu pond/peony in a basket by odano naotake 21 We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for their English editing. akita ranga sketch books 22 Copyright©2018 development of akita ranga 24 Akita International University Institute for Asian Studies and Regional Collaboration double spiral staircase 27 ISBN 978-4-9908872-5-4 akita ranga tragedy: sudden demise 28 Printed in Japan Influence on european art and akita ranga today 31 short bibliography and figures 32 3 Foreword/Acknowledgements This is a booklet that, regardless of its modest size, aims to honor Akita Ranga for its pioneering spirit, noble qualities, and suave elegance of its painting style, attempting to also offer a testimonial page to “our” art history in the world context. -

Press = Herald

(.}M**ilHMi1^H PMSS-HMAID JUNI 21, 1967 when you're there, be sure The Royal Ballet will begin Stop by one of those three and iwing by the Hotel Trop- its engagement with the full- days or ALL ihre«, if eana and dig the melodious length "Giselle" on June 30. you wish, and help Pete and Morgana King who makes her It's "The Sleeping Beauty" Anne help you have a good debut this Friday nite along afternoon and evening of time at BBQ Pete's with comic Don Sherman and July 2. Maynard Ferguson's ork. At the completion of its Altho she's never appeared engagement at the Shrine, yrically anywhere west of the Royal Ballet will move to llinois. Miss King has a Hollywood Bowl to present By Terrcnce O'Flaherty whole bunch of jazz and blues "Swan Lake" on July 14 and successes in N.Y., Chicago, 15, and "Romeo and Juliet" Detroit and Philadelphia. You on July 16 and 17, then its "W* watched the TV It's hard to say for 'sure, Swing With the Swingers might liken her to a Holiday, 'Giselle" on the 18th. E m m y Awards and, ai but certainly Dean Martin Fitzgerald or a Vaughn in tuual, got more pleasure must be in the running. He And in this case the "swingers" are holding a meet to end all meets, like, would her stylings. Don't let next Monday, from watching the losers has just signed an unprece u beliece tomorrow nite .. Thursday, June 22? And its called "The Swing- The walling horn of May Tuesday and Wednesday get, than the winners. -

Newsletter for February 2019

St. Peter’s Press St. Peter’s Presbyterian Church - Spencertown, NY PO Box 14 | 5219 County Route 7 | Spencertown, NY 12165 Telephone: 518.392.3386 | Email: [email protected] Rev. Lynn Horan: Cell Phone 518-847-9115 | Email: [email protected] Website: http://saintpeterspc.org | Facebook: www.facebook.com/saintpeterspc February 2019 Greetings St. Peter’s, As we awaited our recent snow storm, I bundled up at home with a new book that I found in our church worship closet titled Winter: A Spiritual Biography of the Season. The book includes various reflections, poems and even sermons from famous and lesser-known writers, each sharing their thoughts on the spiritual terrain that this season offers. I was especially drawn to a sermon by Rev. William Cooper, a colonial-era preacher from Boston whose sermon on January 23rd, 1736 was aptly titled “A Winter Sermon.” From the wooden chancel of the Brattle Street Church in Cambridge, Rev. Cooper read from the King James Bible, Psalm 147 verses 15-18: God sendeth forth His commandment upon earth, His word runneth very swiftly. He giveth snow like wool, He scattereth the frost like ashes. He casteth forth ice like morsels. Who can stand before this cold? God sendeth out His word, and melteth them, He causeth the wind to blow, and the waters flow. And then, in beautiful 18th century discourse, Rev. Cooper argues that the cold is a very powerful means of spiritual practice and devotion. He also lifts up the need for greater service to one another, both neighbor and stranger, due to the many hardships of this season. -

Most Famous Samples Used from Cerrone

MOST FAMOUS SAMPLES USED FROM CERRONE • Rocket in the Pocket (Live) (1978) was sampled in o Rock the Bells by LL Cool J (1985) o Paul Revere by Beastie Boys (1986) o Return of the Mack by Mark Morrison (1996) see 118 more connections • Love in C Minor (1976) was sampled in o Electricity (Album Version) by The Avalanches (2000) o A Different Feeling by The Avalanches (2000) o Diners Only by The Avalanches (2000) see 5 more connections • Look for Love (1978) was sampled in o I Feel for You by Bob Sinclar (2000) o Santa Claus by Le Knight Club (1997) o Bite This by Roxanne Shanté (1985) see 1 more connection • Supernature (1977) was sampled in o Kilometer (Aeroplane "Italo 84" Remix) by Sébastien Tellier (2009) o Rap Info by Rohff (2001) o Devine Rule by Guru (2009) see 2 more connections • Rocket in the Pocket (1978) was sampled in o On Fire by Modjo (2001) o We Got This by The Alchemist feat. Prodigy (2006) sampled o La Marseillaise by Claude Joseph Rouget De Lisle (1792) • Give Me Love (1977) was sampled in o Intergalactik Disko by Le Knight Club and DJ Sneak (1998) o Rollercoaster by Modjo (2001) o Give Me Love by Saldano (1996) see 1 more connection • In the Smoke (1977) was sampled in o Venom by Arsonists (1999) o King From Queens by Infamous Mobb feat. A-Dog (2004) o Other Side by Avatar Young Blaze (2012) see 2 more connections • Love Is the Answer (1977) was sampled in o Coco Girlz by Le Knight Club (1999) o Love Is the Answer by Africanism (2001) • You Are the One (1981) was sampled in o Discotirso by Knightlife (2009) o Run Baby Run by Busta Funk (2001) o Funky Man by Mike 303 (2000) see 1 more connection • Je Suis Music (Armand Van Helden Remix) (2004) sampled o Don't Push It Don't Force It by Leon Haywood (1980) is a remix of o Je Suis Music by Cerrone (1978) • My Look (1980) was sampled in o Hysteria by Cerrone (2002) o Sola by Spiller feat. -

David A. Gemmell's First Novellegend, a Powerful Heroic Fantasy, Was Published in 1984

Generated by ABC Amber LIT Converter, http://www.processtext.com/abclit.html David A. Gemmell's first novelLegend, a powerful heroic fantasy, was published in 1984. Since then he has become a full-time writer and his bestsellers include the Jon Shannow novels,Wolf in Shadow, The Last Guardian andBloodstone, the continuingDrenai series, andThe First Chronicles of Druss the Legend. His most recent bestsellers,Sword in the Storm, Echoes of the Great Song andMidnight Falcon, are also published by Corgi. David Gemmell is married with two teenage children and lives in East Sussex. By David Gemmell The Drenai books Legend The King Beyond the Gate Waylander Quest for Lost Heroes Waylander 2: In the Realm of the Wolf The First Chronicles of Druss the Legend The Legend of Deathwalker Winter Warriors Hero in the Shadows The Jon Shannow books Wolf in Shadow The Last Guardian Bloodstone The Stones of Power books Ghost King Last Sword of Power Lion of Macedon Generated by ABC Amber LIT Converter, http://www.processtext.com/abclit.html Dark Prince The Hawk Queen books Ironhand's Daughter The Hawk Eternal The Rigante books Sword in the Storm Midnight Falcon Ravenheart Individual titles Knights of Dark Renown Drenai Tales Morning Star Dark Moon Echoes of the Great Song THE LEGEND OF DEATHWALKER David A. Gemmell CORGI BOOKS THE LEGEND OF DEATHWALKER A CORGI BOOK : 0 551 14252 2 Originally published in Great Britain by Bantam Press, Generated by ABC Amber LIT Converter, http://www.processtext.com/abclit.html a division of Transworld Publishers PRINTING HISTORY Bantam Press edition published 1996 Corgi edition published 1996 7 9 10 8 6 Copyright © David Gemmell 1996 The right of David Gemmell to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.