Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calvinism in the Context of the Afrikaner Nationalist Ideology

ASIAN AND AFRICAN STUDIES, 78, 2009, 2, 305-323 CALVINISM IN THE CONTEXT OF THE AFRIKANER NATIONALIST IDEOLOGY Jela D o bo šo vá Institute of Oriental Studies, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Klemensova 19, 813 64 Bratislava, Slovakia [email protected] Calvinism was a part of the mythic history of Afrikaners; however, it was only a specific interpretation of history that made it a part of the ideology of the Afrikaner nationalists. Calvinism came to South Africa with the first Dutch settlers. There is no historical evidence that indicates that the first settlers were deeply religious, but they were worshippers in the Nederlands Hervormde Kerk (Dutch Reformed Church), which was the only church permitted in the region until 1778. After almost 200 years, Afrikaner nationalism developed and connected itself with Calvinism. This happened due to the theoretical and ideological approach of S. J.du Toit and a man referred to as its ‘creator’, Paul Kruger. The ideology was highly influenced by historical developments in the Netherlands in the late 19th century and by the spread of neo-Calvinism and Christian nationalism there. It is no accident, then, that it was during the 19th century when the mythic history of South Africa itself developed and that Calvinism would play such a prominent role in it. It became the first religion of the Afrikaners, a distinguishing factor in the multicultural and multiethnic society that existed there at the time. It legitimised early thoughts of a segregationist policy and was misused for political intentions. Key words: Afrikaner, Afrikaner nationalism, Calvinism, neo-Calvinism, Christian nationalism, segregation, apartheid, South Africa, Great Trek, mythic history, Nazi regime, racial theories Calvinism came to South Africa in 1652, but there is no historical evidence that the settlers who came there at that time were Calvinists. -

DISSERTATION O Attribution

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/vital/access/manager/Index?site_name=Research%20Output (Accessed: Date). The design of a vehicular traffic flow prediction model for Gauteng freeways using ensemble learning by TEBOGO EMMA MAKABA A dissertation submitted in fulfilment for the Degree of Magister Commercii in Information Technology Management Faculty of Management UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG Supervisor: Dr B.N Gatsheni 2016 DECLARATION I certify that the dissertation submitted by me for the degree Master’s of Commerce (Information Technology Management) at the University of Johannesburg is my independent work and has not been submitted by me for a degree at another university. TEBOGO EMMA MAKABA i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I hereby wish to express my gratitude to the following individuals who enabled this document to be successfully and timeously completed: Firstly, GOD Supervisor, Dr BN Gatsheni Mikros Traffic Monitoring(Pty) Ltd (MTM) for providing me with the traffic flow data My family and friends Prof M Pillay and Ms N Eland Faculty of Management for funding me with the NRF Supervisor linked bursary ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to everyone who supported me during the project, from the start till the end. -

The Gordian Knot: Apartheid & the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order, 1960-1970

THE GORDIAN KNOT: APARTHEID & THE UNMAKING OF THE LIBERAL WORLD ORDER, 1960-1970 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Ryan Irwin, B.A., M.A. History ***** The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Peter Hahn Professor Robert McMahon Professor Kevin Boyle Professor Martha van Wyk © 2010 by Ryan Irwin All rights reserved. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the apartheid debate from an international perspective. Positioned at the methodological intersection of intellectual and diplomatic history, it examines how, where, and why African nationalists, Afrikaner nationalists, and American liberals contested South Africa’s place in the global community in the 1960s. It uses this fight to explore the contradictions of international politics in the decade after second-wave decolonization. The apartheid debate was never at the center of global affairs in this period, but it rallied international opinions in ways that attached particular meanings to concepts of development, order, justice, and freedom. As such, the debate about South Africa provides a microcosm of the larger postcolonial moment, exposing the deep-seated differences between politicians and policymakers in the First and Third Worlds, as well as the paradoxical nature of change in the late twentieth century. This dissertation tells three interlocking stories. First, it charts the rise and fall of African nationalism. For a brief yet important moment in the early and mid-1960s, African nationalists felt genuinely that they could remake global norms in Africa’s image and abolish the ideology of white supremacy through U.N. -

Trouble Flares up at Mabieskraal

, 8 .~ · le bv si b k ' d" I£tl1l1l1ll1l1l1l1ll1l"""III1I1I11I11I11 I1 " II " II I1I1 I11 I1 " ~l l11 l1 m lll IIIIII III Bantustan IS rue Y slam 0 In Isgulse ... 1• ••• •• ••• 1 Congress reiects the concept of national homes § for Africans ...We claim the whole of South Africa as our home Vol. 5, No, 51 Registered. at the G.P.O. as a Newspaper 6di= _ SOUTHERNEDITION Thursday, October 8, 1959 • 5 ~1I"1II"III11I1I11I11I1I11I11I1 I1I11" nllllll lllllll lll ll ll ll ll ll ll ll lll l lll lll lll lll ll ll ll lll lll lll ll lllll ll ll ll ll lll ll l1 1I 111 11111 11 ~ oWHAT KH USCHOV TOLD THE U.S.A. The verbatim record no other news Slap In The Face For E~ic Louw paper in South Africa has printed JOHANNESBURG as their home", Iin South Africa during the last two B~~~~~ aF~:~naft~i~1~~~ whT: ~[r~~e s~b~ftt~J~~~f~:~~~ ye~~~l i n g ~ith so-called Ban.tusta!1s ~r. Eric Louw had mad.e ,bis ~:~~ r:, i ~ s ~~o ~i v~f t~~e A9ri~~~a~i~~: ~o~~r~~~~~l s ~:dt e~~ ~ h~ f ~h~ o~~~I~ ~ .- Pages 4 and 5 big speech to U.N: D., claiming point on trends and developments Continued 011 page 7 that the Bantu territories would 1 -------------------- I(!1:~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ eventually form part of a South African Commonwealth toge ther with White South Africa, the African National Congress has sent a memorandum to ~;:t~' :he:~ri~i::tu~~~n ~~~~:; as a gigantic fraud. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

The Referendum in FW De Klerk's War of Manoeuvre

The referendum in F.W. de Klerk’s war of manoeuvre: An historical institutionalist account of the 1992 referendum. Gary Sussman. London School of Economics and Political Science. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government and International History, 2003 UMI Number: U615725 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615725 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 T h e s e s . F 35 SS . Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract: This study presents an original effort to explain referendum use through political science institutionalism and contributes to both the comparative referendum and institutionalist literatures, and to the political history of South Africa. Its source materials are numerous archival collections, newspapers and over 40 personal interviews. This study addresses two questions relating to F.W. de Klerk's use of the referendum mechanism in 1992. The first is why he used the mechanism, highlighting its role in the context of the early stages of his quest for a managed transition. -

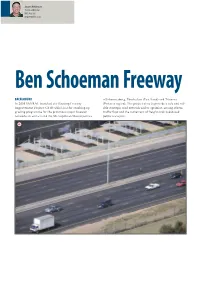

Ben Schoeman Freeway

Jurgens Weidemann Technical Director BKS (Pty) Ltd [email protected] Ben Schoeman Freeway BACKGROUND of Johannesburg, Ekurhuleni (East Rand) and Tshwane In 2008 SANRAL launched the Gauteng Freeway (Pretoria region). The project aims to provide a safe and reli- Improvement Project (GFIP) which is a far-reaching up- able strategic road network and to optimise, among others, grading programme for the province’s major freeway traffic flow and the movement of freight and road-based networks in and around the Metropolitan Municipalities public transport. 1 The GFIP is being implemented in phases. The first phase 1 Widened to five lanes per carriageway comprises the improvement of approximately 180 km of 2 Bridge widening at the Jukskei River existing freeways and includes 16 contractual packages. The 3 Placing beams at Le Roux overpass network improvement comprises the adding of lanes and up- 4 Brakfontein interchange – adding a third lane grading of interchanges. Th e upgrading of the Ben Schoeman Freeway (Work Package 2 C of the GFIP) is described in this article. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES Th e upgraded and expanded freeways will signifi cantly re- duce traffi c congestion and unblock access to economic op- portunities and social development projects. Th e GFIP will provide an interconnected freeway system between the City of Johannesburg and the City of Tshwane, this system currently being one of the main arteries within the north-south corridor. One of the most significant aims of this investment for ordinary citizens is the reduction of travel times since many productive hours are wasted as a result of long travel times. -

SOUTK Afftica's EXPANDING RELATIONS with LATIN AMERICA, 1966-1976 W David Fig

SOUTK AFFtICA'S EXPANDING RELATIONS WITH LATIN AMERICA, 1966-1976 W David Fig The documentation of South Africa's relations with Latin America has previously received only cursory mention in work on contemporary South African history. This paper seeks to examine the significance of these relations and to raise a number of pertinent questions about the role of the state in its efforts to promote suoh linkages. Althou& trade relations existed since the early nineteenth century (l), and South Africa had limited diplomatic representation in Argentina and Brazil since 1938 and 1943, respectively (2), it is only in the last dozen years that relations with Latin America have been expanded significantly. The conjuncture of the mid-1960s in South Africa saw a period of sustained expansion of the gross domestic product which was assisted by new injections of foreign inves-tment following the severe repression of the nationalist movement. But "growth11required the importation of large amounts of expensive and sophisticated capital goods, and this took place at a much faster rate than did the increase in exports. South African exports - two-thirds of which consisted of primary products - had to overcome the adverse effects of an inflationary cost structure, and it became imperative that new markets for manufactured products be found, especially because it was feared that gold production would plateau and decline in view of the constant official price. Although Africa seemed the ideal target for a South African sub-imperial role, numerous political constraints presented themselves, only to be compounded later, after the abortive attempts at "dialogue" and ltdetente'l.Manufactured goods were also unlikely to be competitive with those produced in western Europe and North America, South Africa's traditional markets for primary products. -

Fascist Or Opportunist?”: the Political Career of Oswald Pirow, 1915–1943

Historia, 63, 2, November 2018, pp 93-111 “Fascist or opportunist?”: The political career of Oswald Pirow, 1915–1943 F.A. Mouton* Abstract Oswald Pirow’s established place in South African historiography is that of a confirmed fascist, but in reality he was an opportunist. Raw ambition was the underlying motive for every political action he took and he had a ruthless ability to adjust his sails to prevailing political winds. He hitched his ambitions to the political momentum of influential persons such as Tielman Roos and J.B.M. Hertzog in the National Party with flattery and avowals of unquestioning loyalty. As a Roos acolyte he was an uncompromising republican, while as a Hertzog loyalist he rejected republicanism and national-socialism, and was a friend of the Jewish community. After September 1939 with the collapse of the Hertzog government and with Nazi Germany seemingly winning the Second World War, overnight he became a radical republican, a national-socialist and an anti-Semite. The essence of his political belief was not national-socialism, but winning, and the opportunistic advancement of his career. Pirow’s founding of the national-socialist movement, the New Order in 1940 was a gamble that “went for broke” on a German victory. Keywords: Oswald Pirow; New Order; fascism; Nazi Germany; opportunism; Tielman Roos; J.B.M. Hertzog; ambition; Second World War. Opsomming In die Suid-Afrikaanse historiografie word Oswald Pirow getipeer as ’n oortuigde fascis, maar in werklikheid was hy ’n opportunis. Rou ambisie was die onderliggende motivering van alle politieke handelinge deur hom. Hy het die onverbiddelike vermoë gehad om sy seile na heersende politieke winde te span. -

Die Burger Se Rol in Die Suid-Afrikaanse Partypolitiek, 1934 - 1948

DIE BURGER SE ROL IN DIE SUID-AFRIKAANSE PARTYPOLITIEK, 1934 - 1948 deur JURIE JACOBUS JOUBERT voorgelê luidens die vereistes vir die graad D. LITT ET PHIL in die vak GESKIEDENIS aan die UNIVERSITEIT VAN SUID-AFRIKA PROMOTOR: PROFESSOR C.F.J. MULLER MEDE-PROMOTOR: PROFESSOR J.P. BRITS JUNIE 1990 THE PRESENCE GF DIE BURGER IN THE PARTYPOLITICS DF SOUTH AFRICA, 1934 - 1948 by JURIE JACOBUS JOUBERT Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER : PROFESSOR C.F.J. MULLER JOINT PROMOTER : PROFESSOR J.P. BRITS JUNE 1990 U N f S A BIBLIOTPPK AS9U .1 a Class KÍas ..J & t e Access I Aanwin _ 01326696 "Ek verklaar hiermee dat Die Burger se rol in die Suid-Afrikaanse Partypolitiek, 1934 - 1948 my eie werk is en dat ek alle bronne wat ek gebruik of aangehaal het deur middel van volledige verwyeyigs aangecfyi en erken het" lU t (i) SUMMARY During the nineteen thirties and forties the Afrikaans newspaper Die Burger occupied a prominent place within the ambience of the South African press. Without reaching large circulation figures, it achieved recognition and respect because - apart from other reasons - it commanded the skills of a very competent editorial staff and management team. The way in which it effectively ousted its main rival Die Suiderstem, is testimony of its power and influence, particularly in its hinterland. The close association between Die Burger and the Cape National Party represented a formidable joining of forces. This relation ship, entailing mutual advantages, was sustained significantly by the involvement of Dr. -

Inhoudsopgawe

Inhoudsopgawe Voorwoord 2 ons spore lê Ver oor die land 5 ons Vier ons Vryheid in ons land 7 ons Vorm die toekoms Van ons land 15 Voortrekkerspore oor 85 jaar ons Vure sal steeds helder brand 64 die fakkel word aangesteek op kerkenberg en retiefpas 64 kaapland kimberley 72 George 74 paarl 77 port elizabeth 81 namibië Fees in swakopmund 83 Feeskamp myl 4 84 Vrystaat en natal Vegkop 86 bloemfontein 88 bloedrivier 92 transVaal limpopo fietstrap 93 monumentkoppie 95 Feesdiens, Voortrekkermonument 99 ons almal bou ’n heGte band 102 dankie is ’n woordjie wat ons opreG bedoel 113 ons wil ons harte Vir jou wys 114 ons is diensbaar hier en in elke huis 116 Voorwoord Vanjaar het Die Voortrekkers 85 jaar se spore gevier. Tagtig jaar gelede, in 1936, het die eerste Hou Koers die lig gesien. Aanvanklik was die Hou Koers bedoel as ’n kwartaalblad vir die Voortrekkeroffisiere van Kaapland, maar sedert 1939 is dit nasionaal versprei as ’n kwartaallikse opleidingsblad vir Voortrekkeroffisiere. dit was te danke aan die persone soos japie heese, oom Vossie, Nig Sterretjie en Thys Greeff wat die Hou Koers-blad ontwikkel het tot ’n trotse tradisie. Die Hou Koers-jaarblad bou jaarliks steeds voort op die trotse tradisie. die jaarblad, met die feestema: Trap nuwe spore, gee nie net ’n oorsig oor die Voortrekkerspore van die afgelope feesjaar nie, maar kyk verder terug tot waar die droom van ’n eie Afrikaanse jeugbeweging in 1913 die eerste keer begin het. daar is heeltemal te min spasie om erkenning te gee aan die letterlik duisende Voortrekkers wat oor dekades diep spore getrap het. -

The Sadf Conscript Generation and Its Search for Healing, Reconciliation and Social Justice

THE SADF CONSCRIPT GENERATION AND ITS SEARCH FOR HEALING, RECONCILIATION AND SOCIAL JUSTICE A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Philosophiae Doctor in the Practical and Missional Theology department Faculty of Theology and Religion University of the Free State Pieter Hendrik Schalk Bezuidenhout Study leader: Prof. P. Verster Bloemfontein January 2015 Translated by Suzanne Storbeck (June 2020) DECLARATION (i) I, Pieter Hendrik Schalk Bezuidenhout, declare that this thesis, submitted to the University of the Free State in fulfilment for the degree Philosophiae Doctor, is my own work and that it has not been handed in at any other university or higher education institution. (ii) I, Pieter Hendrik Schalk Bezuidenhout, declare that I am aware that the copyright of this thesis belongs to the University of the Free State. (iii) I, Pieter Hendrik Schalk Bezuidenhout, declare that the property rights of any intellectual property developed during the study and/or in connection with the study, will be seated in the University of the Free State. i ABSTRACT The former (Afrikaner) SADF conscript generation is to a large extent experiencing an identity crisis. This crisis is due to two factors. First of all, there is a new dispensation where Afrikaners are a minority group. They feel alienated, even frustrated and confused. Secondly, their identity has been challenged and some would say defeated. What is their role and new identity in the current SA? They fought a war and participated internally in operations within a specific local, regional and global context. This identity was formed through their own particular history as well as certain theological and ideological worldviews and frameworks.