Download Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gjoa Haven © Nunavut Tourism

NUNAVUT COASTAL RESOURCE INVENTORY ᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ Department of Environment Avatiliqiyikkut Ministère de l’Environnement Gjoa Haven © Nunavut Tourism ᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ Department of Environment Avatiliqiyikkut NUNAVUT COASTAL RESOURCE INVENTORY • Gjoa Haven INVENTORY RESOURCE COASTAL NUNAVUT Ministère de l’Environnement Nunavut Coastal Resource Inventory – Gjoa Haven 2011 Department of Environment Fisheries and Sealing Division Box 1000 Station 1310 Iqaluit, Nunavut, X0A 0H0 GJOA HAVEN Inventory deliverables include: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • A final report summarizing all of the activities This report is derived from the Hamlet of Gjoa Haven undertaken as part of this project; and represents one component of the Nunavut Coastal Resource Inventory (NCRI). “Coastal inventory”, as used • Provision of the coastal resource inventory in a GIS here, refers to the collection of information on coastal database; resources and activities gained from community interviews, research, reports, maps, and other resources. This data is • Large-format resource inventory maps for the Hamlet presented in a series of maps. of Gjoa Haven, Nunavut; and Coastal resource inventories have been conducted in • Key recommendations on both the use of this study as many jurisdictions throughout Canada, notably along the well as future initiatives. Atlantic and Pacific coasts. These inventories have been used as a means of gathering reliable information on During the course of this project, Gjoa Haven was visited on coastal resources to facilitate their strategic assessment, two occasions: -

Canada Topographical

University of Waikato Library: Map Collection Canada: topographical maps 1: 250,000 The Map Collection of the University of Waikato Library contains a comprehensive collection of maps from around the world with detailed coverage of New Zealand and the Pacific : Editions are first unless stated. These maps are held in storage on Level 1 Please ask a librarian if you would like to use one: Coverage of Canadian Provinces Province Covered by sectors On pages Alberta 72-74 and 82-84 pp. 14, 16 British Columbia 82-83, 92-94, 102-104 and 114 pp. 16-20 Manitoba 52-54 and 62-64 pp. 10, 12 New Brunswick 21 and 22 p. 3 Newfoundland and Labrador 01-02, 11, 13-14 and 23-25) pp. 1-4 Northwest Territories 65-66, 75-79, 85-89, 95-99 and 105-107) pp. 12-21 Nova Scotia 11 and 20-210) pp. 2-3 Nunavut 15-16, 25-27, 29, 35-39, 45-49, 55-59, 65-69, 76-79, pp. 3-7, 9-13, 86-87, 120, 340 and 560 15, 21 Ontario 30-32, 40-44 and 52-54 pp. 5, 6, 8-10 Prince Edward Island 11 and 21 p. 2 Quebec 11-14, 21-25 and 31-35 pp. 2-7 Saskatchewan 62-63 and 72-74 pp. 12, 14 Yukon 95,105-106 and 115-117 pp. 18, 20-21 The sector numbers begin in the southeast of Canada: They proceed west and north. 001 Newfoundland 001K Trepassey 3rd ed. 1989 001L St: Lawrence 4th ed. 1989 001M Belleoram 3rd ed. -

PER ARDUA AD ARCTICUM the Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic

PER ARDUA AD ARCTICUM The Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic Edward P. Wood Edited and introduced by P. Whitney Lackenbauer Mulroney Institute of Government Arctic Operational Histories, no. 2 PER ARDUA AD ARCTICUM The Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic © The author/editor 2017 Mulroney Institute St. Francis Xavier University 5005 Chapel Square Antigonish, Nova Scotia, Canada B2G 2W5 LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Per Ardua ad Arcticum: The Royal Canadian Air Force in the A rctic and Sub- Arctic / Edward P. Wood, author / P. Whitney Lackenbauer, editor (Arctic Operational Histories, no. 2) Issued in electronic and print formats ISBN (digital): 978-1-7750774-8-0 ISBN (paper): 978-1-7750774-7-3 1. Canada. Canadian Armed Forces—History--20th century. 2. Aeronautics-- Canada, Northern--History. 3. Air pilots--Canada, Northern. 4. Royal Canadian Air Force--History. 5. Canada, Northern--Strategic aspects. 6. Arctic regions--Strategic aspects. 7. Canada, Northern—History—20th century. I. Edward P. Wood, author II. Lackenbauer, P. Whitney Lackenbauer, editor III. Mulroney Institute of Government, issuing body IV. Per Adua ad Arcticum: The Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic. V. Series: Arctic Operational Histories; no.2 Page design and typesetting by Ryan Dean and P. Whitney Lackenbauer Cover design by P. Whitney Lackenbauer Please consider the environment before printing this e-book PER ARDUA AD ARCTICUM The Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic Edward P. Wood Edited and Introduced by P. Whitney Lackenbauer Arctic Operational Histories, no.2 2017 The Arctic Operational Histories The Arctic Operational Histories seeks to provide context and background to Canada’s defence operations and responsibilities in the North by resuscitating important, but forgotten, Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) reports, histories, and defence material from previous generations of Arctic operations. -

POL Volume 2 Issue 16 Back Matter

THE POLAR RECORD INDEX NUMBERS 9—16 JANUARY 1935—JULY 1938 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN FOR THE SCOTT POLAR RESEARCH INSTITUTE CAMBRIDGE: AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1939 THE POLAR RECORD INDEX Nos. 9-16 JANUARY 1935—JULY 1938 The names of ships are in italics. Expedition titles are listed separately at Uie end Aagaard, Bjarne, II. 112 Alazei Mountains, 15. 5 Abruzzi, Duke of, 15. 2 Alazei Plateau, 12. 125 Adams, Cdr. .1. B., 9. 72 Alazei River, 14. 95, 15. 6 Adams, M. B., 16. 71 Albert I Peninsula, 13. 22 Adderley, J. A., 16. 97 Albert Harbour, 14. 136 Adelaer, Cape, 11. 32 Alberta, 9. 50 Adelaide Island, 11. 99, 12. 102, 103, 13. Aldan, 11. 7 84, 14. 147 Aldinger, Dr H., 12. 138 Adelaide Peninsula, 14. 139 Alert, 11. 3 Admiralty Inlet, 13. 49, 14. 134, 15. 38 Aleutian Islands, 9. 40-47, 11. 71, 12. Advent Bay, 10. 81, 82, 11. 18, 13. 21, 128, 13. 52, 53, 14. 173, 15. 49, 16. 15. 4, 16. 79, 81 118 Adytcha, River, 14. 109 Aleutian Mountains, 13. 53 Aegyr, 13. 30 Alexander, Cape, 11. GO, 15. 40 Aerial Surveys, see Flights Alexander I Land, 12. 103, KM, 13. 85, Aerodrome Bay, II. 59 80, 14. 147, 1-19-152 Aeroplanes, 9. 20-30, 04, (i5-(>8, 10. 102, Alcxamtrov, —, 13. 13 II. 60, 75, 79, 101, 12. 15«, 158, 13. Alexcyev, A. D., 9. 15, 14. 102, 15. Ki, 88, 14. 142, 158-103, 16. 92, 93, 94, 16. 92,93, see also unilcr Flights Alftiimyri, 15. -

Cultural Heritage Resources Report & Inventory

Phase I: NTI IIBA for Cultural Heritage Resources Conservation Areas Report and Inventory Appedices Cultural Heritage Area: Queen Maud Gulf and Interpretative Migratory Bird Sanctuary Materials Study Prepared for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 1 May 2011 This report is part of a set of studies and a database produced for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. as part of the project: NTI IIBA for Conservation Areas, Cultural Resources Inventory and Interpretative Materials Study Inquiries concerning this project and the report should be addressed to: David Kunuk Director of Implementation Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 3rd Floor, Igluvut Bldg. P.O. Box 638 Iqaluit, Nunavut X0A 0H0 E: [email protected] T: (867) 975‐4900 Project Manager, Consulting Team: Julie Harris Contentworks Inc. 137 Second Avenue, Suite 1 Ottawa, ON K1S 2H4 Tel: (613) 730‐4059 Email: [email protected] Report Authors: Philip Goldring, Consultant: Historian and Heritage/Place Names Specialist (primary author) Julie Harris, Contentworks Inc.: Heritage Specialist and Historian Nicole Brandon, Consultant: Archaeologist Note on Place Names: The current official names of places are used here except in direct quotations from historical documents. Throughout the document Umingmaktok, for example, refers to the settlement previously known as Bay Chimo. Names of places that do not have official names will appear as they are found in the source documents. Contents Section 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................... -

Close World-System Encounters on the Western/Central Arctic Periphery: Long-Term Historic Copper Inuit-European

Close World-System Encounters on the Western/Central Canadian Arctic Periphery: Long-term Historic Copper Inuit-European and Eurocanadian Intersocietal Interaction by Donald S. Johnson A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Individual Interdisciplinary Program University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © Don Johnson, 2010 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70313-7 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70313-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

View of This Thesis As the External Examiner on the Supervisory Committee

University of Alberta Geology, geochronology, thermobarometry, and tectonic evolution of the Queen Maud block, Churchill craton, Nunavut, Canada by Daniel B. Tersmette A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences ©Daniel B. Tersmette Spring 2012 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Dedication For Tawny Abstract The Queen Maud block is divided into two crustal belts. The western Perry River belt is dominated by Mesoarchean to Neoarchean granitic gneisses and supracrustal rocks; it was incorporated into the Rae domain by at least 2.46 Ga. The eastern Paalliq belt is dominated by the 2.52-2.45 Ga Queen Maud granitoids and the 2.45-2.39 Ga Sherman supracrustal sequence, both of which were formed on Neoarchean crust of the Rae domain. Slave-Churchill collision and convergence occurred ca. 2.43-2.35 Ga resulting in granulite-facies metamorphism, regional scale N-S trending strike-slip shearing, and minor crustal melting in the Queen Maud block. -

Pre-Hearing Kimmirut Community History V3

Phase I: NTI IIBA for Cultural Heritage Resources Conservation Areas Report and Inventory Appendices Cultural Heritage Area: Queen Maud Gulf and Interpretative Migratory Bird Sanctuary Materials Study Volume 2 of 2 Prepared for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 1 May 2011 This report is part of a set of studies and a database produced for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. as part of the project: NTI IIBA for Conservation Areas, Cultural Resources Inventory and Interpretative Materials Study Inquiries concerning this project and the report should be addressed to: David Kunuk Director of Implementation Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 3rd Floor, Igluvut Bldg. P.O. Box 638 Iqaluit, Nunavut X0A 0H0 E: [email protected] T: (867) 975‐4900 Project Manager, Consulting Team: Julie Harris Contentworks Inc. 137 Second Avenue, Suite 1 Ottawa, ON K1S 2H4 Tel: (613) 730‐4059 Email: [email protected] Report Authors: Philip Goldring, Consultant: Historian and Heritage/Place Names Specialist (primary author) Julie Harris, Contentworks Inc.: Heritage Specialist and Historian Nicole Brandon, Consultant: Archaeologist Note on Place Names: The current official names of places are used here except in direct quotations from historical documents. Throughout the document Umingmaktok, for example, refers to the settlement previously known as Bay Chimo. Names of places that do not have official names will appear as they are found in the source documents. Contents Section 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................... -

Department of the Interior

Vol. 81 Monday, No. 59 March 28, 2016 Part III Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 20 Migratory Bird Hunting; Final Frameworks for Migratory Bird Hunting Regulations; Final Rule VerDate Sep<11>2014 15:19 Mar 25, 2016 Jkt 238001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\28MRR3.SGM 28MRR3 Lhorne on DSK5TPTVN1PROD with RULES3 17302 Federal Register / Vol. 81, No. 59 / Monday, March 28, 2016 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR regulations process, and addressed the received written comments. establishment of seasons, limits, and Consequently, the issues do not follow Fish and Wildlife Service other regulations for hunting migratory in successive numerical order. game birds under §§ 20.101 through We received recommendations from 50 CFR Part 20 20.107, 20.109, and 20.110 of subpart K. all four Flyway Councils. Some recommendations supported [Docket No. FWS–HQ–MB–2015–0034; Major steps in the 2016–17 regulatory FF09M21200–167–FXMB1231099BPP0] cycle relating to open public meetings continuation of last year’s frameworks. and Federal Register notifications were Due to the comprehensive nature of the RIN 1018–BA70 also identified in the August 6, 2015, annual review of the frameworks proposed rule. Further, we explained performed by the Councils, support for Migratory Bird Hunting; Final that all sections of subsequent continuation of last year’s frameworks is Frameworks for Migratory Bird Hunting documents outlining hunting assumed for items for which no Regulations frameworks and guidelines were recommendations were received. AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, organized under numbered headings. Council recommendations for changes Interior. -

Download Oa File

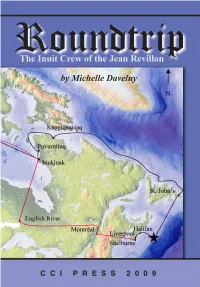

Roundtrip: The Inuit Crew of the Jean Revillon Michelle Daveluy Canadian Circumpolar Institute Press 2009 i Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Daveluy, Michelle, 1960– Roundtrip: The Inuit Crew of the Jean Revillon (Occasional publications series, ISSN 0068-0303; no. 63) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-896445-47-2 1. Inuit—Travel—Nova Scotia—History. 2. Inuit—Nova Scotia—Biography. 3. Sailors—Nunavut—Biography. 4. Jean Revillon (Ship). I. Title.. II. Series: Occasional publication series (Canadian Circumpolar Institute); no. 63. E99.E7D355 2009 971.6’2500497120922 C2009-905938-X KEYWORDS: Inuit, Nunavut, Baker Lake, Jean Revillon crews, shipbuilding, Nova Scotia, Liverpool, NunaScotia, © 2009 CCI Press, University of Alberta All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the express written permission of the copyright owner/s. CCI Press is a registered publisher with access© the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Publisher Number 3524) Cover design by art design printing inc. Front cover images courtesy Lara Bishop and Lisa Hareuther (map), LouisTaapatai and Peter Irniq (Inuit Crew); and Archives Revillon (Jean Revillon). Printed in Canada (Edmonton, Alberta) by art design printing inc. See acknowledgements section of this volume for support of this publication. ISBN-13 978-1-896445-47-2; ISSN 0068-0303 Occasional Publication Number 63 -

The Biogeography of Marbled Godwit (Limosa Fedoa) Populations in North America

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 12-2011 The Biogeography of Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa) Populations in North America Bridget E. Olson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Olson, Bridget E., "The Biogeography of Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa) Populations in North America" (2011). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 1119. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/1119 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BIOGEOGRAPHY OF MARBLED GODWIT (LIMOSA FEDOA) POPULATIONS IN NORTH AMERICA by Bridget E. Olson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Biology Approved: ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Kimberly A. Sullivan Dr. David Koons Major Professor Committee Member ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Ethan White Dr. Mark McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2011 ii Copyright © Bridget Olson 2011 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT The Biogeography of Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa) Populations in North America by Bridget E. Olson, Master of Science Utah State University, 2011 Major Professor: Dr. Kimberly A. Sullivan Department: Biology We equipped 28 Marbled Godwit from four locations in North America with miniature satellite transmitters to determine migration routes, strategy, and connectivity. Godwits captured in Utah (n = 13) went to breeding sites in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Montana and North Dakota and wintered along the Baja Peninsula and west coast of mainland Mexico. -

Bird Sanctuary Management Plan.Pdf

01 May 2018 Nunavut Wildlife Management Board 3rd Floor Allavik Building P.O. Box 1379 Iqaluit, NU X0A 0H0 Email: [email protected] Pertaining to NWMB’s Regular Meeting No. RM 002-2018: Final Draft Management Plan for the Ahiak Migratory Bird Sanctuary for Consideration by the NWMB for Approval The Ahiak (Queen Maud Gulf) Migratory Bird Sanctuary, located between Umingmaktok, Cambridge Bay and Gjoa Haven in the Kitikmeot region of Nunavut, was created in 1961. Through the Nunavut Agreement, an Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement for National Wildlife Areas and Migratory Bird Sanctuaries in the Nunavut Settlement Area (IIBA) was signed by Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., the three Regional Inuit Associations (Kitikmeot Inuit Association, Kivalliq Inuit Association and Qikiqtani Inuit Association) and the federal Minister of the Environment, Environment and Climate Change Canada (signed first in 2006 and renegotiated in 2016). This IIBA created co-management committees for these protected areas in Nunavut (IIBA Article 3). The Ahiak Migratory Bird Sanctuary is co-managed by Inuit (from Umingmaktok, Cambridge Bay and Gjoa Haven) and the Canadian Wildlife Service (a part of Environment and Climate Change Canada) through the Ahiak Area Co-Management Committee. Part of the mandate of the Ahiak Area Co-Management Committee is to develop a Management Plan for the Ahiak Migratory Bird Sanctuary (IIBA s. 3.2.3(b) and s. 3.5). The Ahiak Area Co- Management Committee completed a draft Management Plan and consulted with the associated communities and other interested parties on the draft (IIBA s. 3.5). As per the IIBA, 3.6.1 The ACMCs [Area Co-Management Committees] shall recommend completed Management Plans to the NWMB [Nunavut Wildlife Management Board] for approval in accordance with sections 5.2.34(c) and 5.3.16 of the NLCA [Nunavut Agreement].