The Use of Character Evidence in Victorian Sodomy Trials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

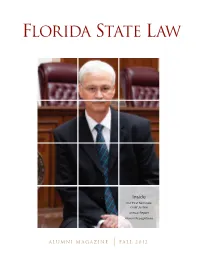

Fall 2012 Florida State Law Magazine

FLORIDA STATE LAW Inside Our First Seminole Chief Justice Annual Report Alumni Recognitions ALUMNI MAGAZINE FALL 2012 Message from the Dean Jobs, Alumni, Students and Admissions Players in the Jobs Market Admissions and Rankings This summer, the Wall Street The national press has highlighted the related phenomena Journal reported that we are the of the tight legal job market and rising student indebtedness. nation’s 25th best law school when it More prospective applicants are asking if a law degree is worth comes to placing our new graduates the cost, and law school applications are down significantly. in jobs that require law degrees. Just Ours have fallen by approximately 30% over the past two years. this month, Law School Transparency Moreover, our “yield” rate has gone down, meaning that fewer ranked us the nation’s 26th best law students are accepting our offers of admission. Our research school in terms of overall placement makes clear: prime competitor schools can offer far more score, and Florida’s best. Our web generous scholarship packages. To attract the top students, page includes more detailed information on our placement we must limit our enrollment and increase scholarship awards. outcomes. In short, we rank very high nationally in terms We are working with our university administration to limit of the number of students successfully placed. Although our our enrollment, which of course has financial implications average starting salary of $58,650 is less than those at the na- both for the law school and for the central university. It is tion’s most elite private law schools, so is our average student also imperative to increase our endowment in a way that will indebtedness, which is $73,113. -

Reform of the Elected Judiciary in Boss Tweed’S New York

File: 3 Lerner - Corrected from Soft Proofs.doc Created on: 10/1/2007 11:25:00 PM Last Printed: 10/7/2007 6:34:00 PM 2007] 109 FROM POPULAR CONTROL TO INDEPENDENCE: REFORM OF THE ELECTED JUDICIARY IN BOSS TWEED’S NEW YORK Renée Lettow Lerner* INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................... 111 I. THE CONSTITUTION OF 1846: POPULAR CONTROL...................... 114 II. “THE THREAT OF HOPELESS BARBARISM”: PROBLEMS WITH THE NEW YORK JUDICIARY AND LEGAL SYSTEM AFTER THE CIVIL WAR .................................................. 116 A. Judicial Elections............................................................ 118 B. Abuse of Injunctive Powers............................................. 122 C. Patronage Problems: Referees and Receivers................ 123 D. Abuse of Criminal Justice ............................................... 126 III. THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1867-68: JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE............................................................. 130 A. Participation of the Bar at the Convention..................... 131 B. Natural Law Theories: The Law as an Apolitical Science ................................... 133 C. Backlash Against the Populist Constitution of 1846....... 134 D. Desire to Lengthen Judicial Tenure................................ 138 E. Ratification of the Judiciary Article................................ 143 IV. THE BAR’S REFORM EFFORTS AFTER THE CONVENTION ............ 144 A. Railroad Scandals and the Times’ Crusade.................... 144 B. Founding -

Detestable Offenses: an Examination of Sodomy Laws from Colonial America to the Nineteenth Century”

“Detestable Offenses: An Examination of Sodomy Laws from Colonial America to the Nineteenth Century” Taylor Runquist Western Illinois University 1 The act of sodomy has a long history of illegality, beginning in England during the reign of Henry VIII in 1533. The view of sodomy as a crime was brought to British America by colonists and was recorded in newspapers and law books alike. Sodomy laws would continue to adapt and change after their initial creation in the colonial era, from a common law offense to a clearly defined criminal act. Sodomy laws were not meant to persecute homosexuals specifically; they were meant to prevent the moral corruption and degradation of society. The definition of homosexuality also continued to adapt and change as the laws changed. Although sodomites had been treated differently in America and England, being a sodomite had the same social effects for the persecuted individual in both countries. The study of homosexuals throughout history is a fairly young field, but those who attempt to study this topic are often faced with the same issues. There are not many historical accounts from homosexuals themselves. This lack of sources can be attributed to their writings being censored, destroyed, or simply not withstanding the test of time. Another problem faced by historians of homosexuality is that a clear identity for homosexuals did not exist until the early 1900s. There are two approaches to trying to handle this lack of identity: the first is to only treat sodomy as an act and not an identity and the other is to attempt to create a homosexual identity for those convicted of sodomy. -

Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015 Todd Barry University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 3-24-2016 From Wilde to Obergefell: Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015 Todd Barry University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Barry, Todd, "From Wilde to Obergefell: Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 1041. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1041 From Wilde to Obergefell: Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015 Todd Barry, PhD University of Connecticut, 2016 This dissertation examines how theatre and law have worked together to produce and regulate gay male lives since the 1895 Oscar Wilde trials. I use the term “gay legal theatre” to label an interdisciplinary body of texts and performances that include legal trials and theatrical productions. Since the Wilde trials, gay legal theatre has entrenched conceptions of gay men in transatlantic culture and influenced the laws governing gay lives and same-sex activity. I explore crucial moments in the history of this unique genre: the Wilde trials; the British theatrical productions performed on the cusp of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act; mainstream gay American theatre in the period preceding the Stonewall Riots and during the AIDS crisis; and finally, the contemporary same-sex marriage debate and the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). The study shows that gay drama has always been in part a legal drama, and legal trials involving gay and lesbian lives have often been infused with crucial theatrical elements in order to legitimize legal gains for LGBT people. -

The Surprising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Proof, 67 Fla

Florida Law Review Volume 67 | Issue 5 Article 2 March 2016 The urS prising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Proof John Leubsdorf Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr Part of the Evidence Commons Recommended Citation John Leubsdorf, The Surprising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Proof, 67 Fla. L. Rev. 1569 (2016). Available at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol67/iss5/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Law Review by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Leubsdorf: The Surprising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Pro THE SURPRISING HISTORY OF THE PREPONDERANCE STANDARD OF CIVIL PROOF John Leubsdorf * Abstract Although much has been written on the history of the requirement of proof of crimes beyond a reasonable doubt, this is the first study to probe the history of its civil counterpart, proof by a preponderance of the evidence. It turns out that the criminal standard did not diverge from a preexisting civil standard, but vice versa. Only in the late eighteenth century, after lawyers and judges began speaking of proof beyond a reasonable doubt, did references to the preponderance standard begin to appear. Moreover, U.S. judges did not start to instruct juries about the preponderance standard until the mid-nineteenth century, and English judges not until after that. The article explores these developments and their causes with the help of published trial transcripts and newspaper reports that have only recently become accessible. -

THE UNIVERSITY of HULL (Neo-)Victorian

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL (Neo-)Victorian Impersonations: 19th Century Transvestism in Contemporary Literature and Culture being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD in the University of Hull by Allison Jayne Neal, BA (Hons), MA September 2012 Contents Contents 1 Acknowledgements 3 List of Illustrations 4 List of Abbreviations 6 Introduction 7 Transvestites in History 19th-21st Century Sexological/Gender Theory Judith Butler, Performativity, and Drag Neo-Victorian Impersonations Thesis Structure Chapter 1: James Barry in Biography and Biofiction 52 ‘I shall have to invent a love affair’: Olga Racster and Jessica Grove’s Dr. James Barry: Her Secret Life ‘Betwixt and Between’: Rachel Holmes’s Scanty Particulars: The Life of Dr James Barry ‘Swaying in the limbo between the safe worlds of either sweet ribbons or breeches’: Patricia Duncker’s James Miranda Barry Conclusion: Biohazards Chapter 2: Class and Race Acts: Dichotomies and Complexities 112 ‘Massa’ and the ‘Drudge’: Hannah Cullwick’s Acts of Class Venus in the Afterlife: Sara Baartman’s Acts of Race Conclusion: (Re)Commodified Similarities Chapter 3: Performing the Performance of Gender 176 ‘Let’s perambulate upon the stage’: Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem ‘All performers dress to suit their stages’: Tipping the Velvet ‘It’s only human nature after all’: Tipping the Velvet and Adaptation 1 Conclusion: ‘All the world’s a stage and all the men and women merely players’ Chapter 4: Cross-Dressing and the Crisis of Sexuality 239 ‘Your costume does not lend itself to verbal declarations’: -

Common Law Judicial Office, Sovereignty, and the Church Of

1 Common Law Judicial Office, Sovereignty, and the Church of England in Restoration England, 1660-1688 David Kearns Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney A thesis submitted to fulfil requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 2 This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. David Kearns 29/06/2019 3 Authorship Attribution Statement This thesis contains material published in David Kearns, ‘Sovereignty and Common Law Judicial Office in Taylor’s Case (1675)’, Law and History Review, 37:2 (2019), 397-429, and material to be published in David Kearns and Ryan Walter, ‘Office, Political Theory, and the Political Theorist’, The Historical Journal (forthcoming). The research for these articles was undertaken as part of the research for this thesis. I am the sole author of the first article and sole author of section I of the co-authored article, and it is the research underpinning section I that appears in the thesis. David Kearns 29/06/2019 As supervisor for the candidature upon which this thesis is based, I can confirm that the authorship attribution statements above are correct. Andrew Fitzmaurice 29/06/2019 4 Acknowledgements Many debts have been incurred in the writing of this thesis, and these acknowledgements must necessarily be a poor repayment for the assistance that has made it possible. -

Cromwellian Anger Was the Passage in 1650 of Repressive Friends'

Cromwelliana The Journal of 2003 'l'ho Crom\\'.Oll Alloooluthm CROMWELLIANA 2003 l'rcoklcnt: Dl' llAlUW CO\l(IA1© l"hD, t'Rl-llmS 1 Editor Jane A. Mills Vice l'l'csidcnts: Right HM Mlchncl l1'oe>t1 l'C Profcssot·JONN MOlUUU.., Dl,llll, F.13A, FlU-IistS Consultant Peter Gaunt Professor lVAN ROOTS, MA, l~S.A, FlU~listS Professor AUSTIN WOOLll'YCH. MA, Dlitt, FBA CONTENTS Professor BLAIR WORDEN, FBA PAT BARNES AGM Lecture 2003. TREWIN COPPLESTON, FRGS By Dr Barry Coward 2 Right Hon FRANK DOBSON, MF Chairman: Dr PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS 350 Years On: Cromwell and the Long Parliament. Honorary Secretary: MICHAEL BYRD By Professor Blair Worden 16 5 Town Farm Close, Pinchbeck, near Spalding, Lincolnshire, PEl 1 3SG Learning the Ropes in 'His Own Fields': Cromwell's Early Sieges in the East Honorary Treasurer: DAVID SMITH Midlands. 3 Bowgrave Copse, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 2NL By Dr Peter Gaunt 27 THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATION was founded in 1935 by the late Rt Hon Writings and Sources VI. Durham University: 'A Pious and laudable work'. By Jane A Mills · Isaac Foot and others to commemorate Oliver Cromwell, the great Puritan 40 statesman, and to encourage the study of the history of his times, his achievements and influence. It is neither political nor sectarian, its aims being The Revolutionary Navy, 1648-1654. essentially historical. The Association seeks to advance its aims in a variety of By Professor Bernard Capp 47 ways, which have included: 'Ancient and Familiar Neighbours': England and Holland on the eve of the a. -

John Sadler (1615-1674) Religion, Common Law, and Reason in Early Modern England

THE PETER TOMASSI ESSAY john sadler (1615-1674) religion, common law, and reason in early modern england pranav kumar jain, university of chicago (2015) major problems. First, religion—the pivotal force I. INTRODUCTION: RE-THINKING EARLY that shaped nearly every aspect of life in seventeenth- MODERN COMMON LAW century England—has received very little attention in ost histories of Early Modern English most accounts of common law. As I will show in the common law focus on a very specific set next section, either religion is not mentioned at all of individuals, namely Justices Edward or treated as parallel to common law. In other words, MCoke and Matthew Hale, Sir Francis Bacon, Sir Henry historians have generally assumed a disconnect Finch, Sir John Doddridge, and-very recently-John between religion and common law during this Selden.i The focus is partly explained by the immense period. Even works that have attempted to examine influence most of these individuals exercised upon the intersection of religion and common law have the study and practice of common law during the argued that the two generally existed in harmony seventeenth century.ii Moreover, according to J.W. or even as allies in service to political motives. Tubbs, such a focus is unavoidable because a great The possibility of tensions between religion and majority of common lawyers left no record of their common law has not been considered at all. Second, thoughts.1 It is my contention that Tubbs’ view is most historians have failed to consider emerging unwarranted. Even if it is impossible to reconstruct alternative ways in which seventeenth-century the thoughts of a vast majority of common lawyers, common lawyers conceptualized the idea of reason there is no reason to limit our studies of common as a foundational pillar of English common law. -

2018 Table of Contents I. Articles

AALS Law and Religion Section Annual Bibliography: 2018 Table of Contents I. Journal Articles ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 III. Special Journal Issues ............................................................................................................................................ 7 III. Monographs ............................................................................................................................................................... 9 IV. Edited Volumes ...................................................................................................................................................... 11 I. Articles Zoe Adams & John Olusegun Adenitire, Ideological Neutrality in the Workplace, 81 MODERN L. REV. 348 (2018) Ryan T. Anderson, A Brave New World of Transgender Policy, 41 HARV. J. L. & PUBLIC POLICY 309 (2018) Ruth Arlow, Kuteh v. Dartfod and Gravesham NHS Trust, 20 ECCLESIASTICAL L. J. 113 (2018) Ruth Arlow, The Reverend J. Gould v. Trustees of St. John’s, Downshire Hill, 20 ECCLESIASTICAL L. J. 241 (2018) Ruth Arlow, Scott v. Stevenson & Reid Ltd: Northern Ireland Fair Employment Tribunal, 20 ECCLESIASTICAL L. J. 245 (2018) Giorgia Baldi, Re-conceptualizing Equality in the Work Place: A Reading of the Latest CJEU’s Opinions over the Practice of Veiling, 7 OXFORD J. L. & RELIG. 296 (2018) Luke Beck, The Role of Religion in the Law of Royal Succession in Canada and -

“He Hath Mingled with the Ungodly”

―HE HATH MINGLED WITH THE UNGODLY‖: THE LIFE OF SIMEON SOLOMON AFTER 1873, WITH A SURVEY OF THE EXTANT WORKS CAROLYN CONROY TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I PH.D. THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART DECEMBER 2009 2 ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on the life and work of the marginalized British Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic homosexual Jewish painter Simeon Solomon (1840-1905) after 1873.This year was fundamental in the artist‘s professional and personal life, because it is the year that he was arrested for attempted sodomy charges in London. The popular view that has been disseminated by the early historiography of Solomon, since before and after his death in 1905, has been to claim that, after this date, the artist led a life that was worthless, both personally and artistically. It has also asserted that this situation was self-inflicted, and that, despite the consistent efforts of his family and friends to return him to the conventions of Victorian middle-class life, he resisted, and that, this resistant was evidence of his ‗deviancy‘. Indeed, for over sixty years, the overall effect of this early historiography has been to defame the character of Solomon and reduce his importance within the Aesthetic movement and the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism. It has also had the effect of relegating the work that he produced after 1873 to either virtual obscurity or critical censure. In fact, it is only recently that a revival of interest in the artist has gained momentum, although the latter part of his life from 1873 has still remained under- researched and unrecorded. -

Nineteenth-Century England

Medical History, 2001, 45: 61-82 The Medical Construction of Homosexuality and its Relation to the Law in Nineteenth-Century England IVAN DALLEY CROZIER* It was clear to him that the experimental method was the only method by which one could arrive at any scientific analysis of the passions.' Historians of homosexuality have paid much attention to the law of England, and particularly to sodomy trials, in order to gauge bothwhat was generally thought ofsame- sex practices in the past, and how the legal profession went about framing such practices as illegal.2 "Unnatural practices" were regarded as a felony in England following Henry VIII's 1533 decree that the "offenders being hereof convict by verdict confession or outlawry shall suffer such paynes ofdeath and losses and penalties oftheir goods chattles debts lands tenaments and hereditaments as felons being accustomed to do accordynge to the order of the Common Lawes of this Realme".3 In 1967, under advice from the Wolfenden Report that the law was not preventing same-sex activity, male homosexual practices carried out in private were decriminalized.4 A great deal ofhistorical attention has been directed towards the law, and especially to the many existing court records, in * Ivan Dalley Crozier, PhD, The Wellcome Trust London, Cassell, 1997; Randolph Trumbach, Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, 'Sex, gender, and sexual identity: male sodomy Euston House, 24 Eversholt Street, London NW1 and female prostitution in Enlightenment lAD. London', J. Hist. Sexuality, 1991-2, 2: 186-203; Jeffrey Weeks, Coming out: homosexual politics in Britain from the nineteenth century to the present, I would like to thank Peter Bartlett, Marina London, Quartet Books, 1977; A N Gilbert, Bollinger, W F Bynum, Katie Fullagar, Alex 'Buggery and the British Navy 1700-1861', J.