Ruling by “Fear and Repression” the Restriction of Freedom of Expression, Association and Assembly in Zambia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Office of the Inspector General

The Office of the Inspector General Country Audit of Global Fund Grants to Zambia Audit Report No: GF-OIG-09-15 Issue Date: 5 October 2010 Country Audit of Global Fund Grants to Zambia Table of contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................... 1 Summary of findings .................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 11 Ministry of Health ........................................................................................ 13 Background ............................................................................................... 13 Achievements and challenges ................................................................... 15 Strengthening grant management ............................................................. 16 Ministry of Finance and National Planning (MOFNP) ............................... 47 Background ............................................................................................... 47 Achievements and challenges ................................................................... 47 Strengthening Grant Management............................................................. 48 Zambia National AIDS Network .................................................................. 59 Background ............................................................................................... 59 Achievements and -

A Changing of the Guards Or a Change of Systems?

BTI 2020 A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? Regional Report Sub-Saharan Africa Nic Cheeseman BTI 2020 | A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? Regional Report Sub-Saharan Africa By Nic Cheeseman Overview of transition processes in Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe This regional report was produced in October 2019. It analyzes the results of the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) 2020 in the review period from 1 February 2017 to 31 January 2019. Author Nic Cheeseman Professor of Democracy and International Development University of Birmingham Responsible Robert Schwarz Senior Project Manager Program Shaping Sustainable Economies Bertelsmann Stiftung Phone 05241 81-81402 [email protected] www.bti-project.org | www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en Please quote as follows: Nic Cheeseman, A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? — BTI Regional Report Sub-Saharan Africa, Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung 2020. https://dx.doi.org/10.11586/2020048 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). Cover: © Freepick.com / https://www.freepik.com/free-vector/close-up-of-magnifying-glass-on- map_2518218.htm A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? — BTI 2020 Report Sub-Saharan Africa | Page 3 Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................... -

CSEC Report on Zambia's 2011 Tripartite Elections

CIVIL SOCIETY ELECTION COALITION (CSEC) 2011 CSEC Report on Zambia’s 2011 Tripartite Elections 20 September 2011 December 2011 CSEC Secretariat, c/o Caritas Zambia Plot 60 Kabulonga Road P. O. Box 31965, Lusaka Zambia ‘CSEC: Promoting transparent and credible elections through monitoring all stages of the 2011 electoral process in Zambia’ 1 FOREWORD Civil society in Zambia has a long history of contributinG to the democratic process throuGh a number of activities carried out by individual orGanisations. As the civil society in the country Geared up to be part of Zambia’s 2011 tripartite elections, the idea and viability of coming up with a coordinated and structured coalition such as CSEC 2011 was unforeseen until about May 2011. Eight (8) civil society orGanizations came toGether, believing in their unique capacities but also acknowledging the Great enerGy that would be realised if the orGanisations worked toGether. CSEC thus provided a unique experience of election monitoring. The CSEC experience has Gave the participatinG civil society orGanisations an opportunity to learn many lessons from the challenges and successes of working for a common purpose in a coalition. While the challenges that CSEC faced (limited time, limited resources and varying orGanisational cultures) made it a not so easy task, such challenges were not insurmountable. It was remarkable thouGh to note that partner orGanizations remained committed to the cause and hence the achievements that were realised by the coalition. For instance the contribution made to Zambia’s 2011 elections by CSEC’s Rapid Response Project (RRP) was just phenomenal. Amidst harassment, threats and denunciations arisinG from an ill informed debate on Parallel Vote Tabulation (PVT), CSEC was able to verify official election results using RRP as alternative concept to PVT. -

Zambia General Elections

Report of the Commonwealth Observer Group ZAMBIA GENERAL ELECTIONS 20 September 2011 COMMONWEALTH SECRETARIAT Table of Contents Chapter 1 ................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 1 Terms of Reference ....................................................................................... 1 Activities ....................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2 ................................................................................................... 3 POLITICAL BACKGROUND ....................................................................... 3 Early History ................................................................................................. 3 Colonial History of Zambia ............................................................................. 3 Post-Independence Politics ............................................................................ 3 2001 General Elections .................................................................................. 4 2006 General Elections .................................................................................. 5 The 2008 Presidential By-Election ................................................................... 5 Other Developments ...................................................................................... 5 Constitutional Review ................................................................................... -

OF ZAMBIA ...Three Infants Among Dead After Overloaded Truck Tips Into

HOME NEWS: FEATURE: ENTERTAINMENT: SPORT: KK in high Rising suicide RS\ FAZ withdraws spirits, says cases source of industry has from hosting Chilufya– p3 concern- p17 potential to U-23 AfCON grow’ – p12 tourney – p24 No. 17,823 timesofzambianewspaper @timesofzambia www.times.co.zm TIMES SATURDAY, JULY 22, 2017 OF ZAMBIA K10 ...Three infants among dead after overloaded 11 killed as truck tips into drainage in Munali hills truck keels over #'%$#+,$ drainage on the Kafue- goods –including a hammer-mill. has died on the spot while four Mission Hospital,” Ms Katongo a speeding truck as the driver “RTSA is saddened by the other people sustained injuries in said. attempted to avoid a pothole. #'-$%+Q++% Mazabuka road on death of 11 people in the Munali an accident which happened on She said the names of the The incident happened around +#"/0$ &301"7,'%&2T &'**1 20$L'! !!'"#,2 -, 2&# $3# Thursday. victims were withheld until the 09:40 hours in the Mitec area on #-++-$ Police said the 40 passengers -Mazabuka road. The crash The accident happened on the next of keen were informed. the Solwezi-Chingola road. ++0+% .#-.*#Q +-,% travelling in the back of a Hino could have been avoided had the Zimba-Kalomo Road at Mayombo Ms Katongo said in a similar North Western province police truck loaded with an assortment passengers used appropriate area. ',!'"#,2Q L'4#V7#0V-*" -7 -$ !&'#$36#,1'-)'"#,2'L'#"2&# 2&#+ 2&0## $Q &4# of goods - including a hammer means of transport,” he said. Police spokesperson Esther Hospital township in Chama deceased as Philip Samona, saying died on the spot while mill - were heading to various Southern Province Minister Katongo said in a statement it district, died after he was hit by he died on the spot. -

Justin Bieber Feels "Remorse" for Selena Gomez As She Continues Treatment It's Been Two Days Since Let Her Health Affect Her," Started to Feel Super 2017

No286 K10 www.diggers.news Tuesday October 16, 2018 IT’S 8 PLANES ...5 from Russia, 2 from Italy plus President’s anti-missile ‘Ferrari in the Sky’ from Israel By Joseph Mwenda Communication Brian Mushimba declined Government has procured eight planes, to answer questions around the deal, five from Russia, two from Italy and one Defence PS Stardy Mwale confirmed that from Israel, government insiders have told govt bought five planes from Russia, but News Diggers. remained mute on aviation deals with Italy After Minister of Transport andand Isreal. To page 6 Don’t give plots, jobs to opposition - Mukanga By Mukosha Funga Mukanga has instructed the opposition. PF elections committee council officials not to give And Mukanga says some chairperson Yamfwa plots or jobs to members of members of parliament are not visiting their constituencies because people are putting them Day of Prayer is just a under pressure with money demands. scam, says Mukuka Meanwhile, Mukanga has By Zondiwe Mbewe asked Eastern Province Harry Kalaba paying a courtesy call on Chief Nyimba Kashingula of the Lozi people in Political researcher Dr Cephas Mukuka says Zambia residents to turn up in Limulunga, Western Province. Harry says he is confident of winning 2021. Story page 11 is swiftly drifting from its proper Christian values into full capacity and vote for hypocrisy as can be seen from the way national affairs are President Edgar Lungu in 2021. being conducted. To page 7 To page 5 PF will win 2021 with ease; we are putting more money in people’s pockets - Mwila By Mukosha Funga Meanwhile, Mwila says the on Chipata’s Feel Free Radio Patriotic Front Secretary Patriotic Front is serious “Face to Face” programme, Rev Sumaili struggles General Davies Mwila about the fight against Monday, Mwila there was no says the Patriotic Front corruption. -

E Tyrant Is Acting, Says HH As

No379 K10 www.diggers.news Tuesday February 26, 2019 e tyrant is acting, says HH as... POLICE SQUEEZEBy Zondiwe Mbewe Police in Lusaka yesterday arrested NDC leader Chishimba Kambwili and piled charges on him before denying him police bond. Among the o ences, the former chief government spokesperson is charged with expressing hatred against a foreign national, which is against Section 70 of the Penal Code, and he has also been slapped with the charge of “failure to obey lawful orders” at the Kenneth Kaunda International Airport where he allegedly breached airport security as he KAMBWILI went to welcome his UK-based wife on Sunday. To page 4 PF, UPND must stop ferrying cadres to by-election areas – Kampyongo By Mirriam Chabala Sunday Interview political parties wanted to Home A airs Minister programme, Kampyongo show that they were still Stephen Kampyongo says said there were a number strong in a given area; lack the importation of cadres of reasons for the ongoing of tolerance and above all, to areas where elections political violence including; importation of cadres. are taking place is the root desperation - where To page 5 cause of political violence. And Kampyongo says the Police Service Commission decided to dismiss o cers HH has betrayed me, who beat up PF cadres in the February 12 Sesheke parliamentary by-election says Maj Kachingwe a er considering factors, By Mirriam Chabala such as the availability of Major Richard Kachingwe says he will continue to Zambians that are willing participate in the political arena amongst men and and to serve the country with women of goodwill and not people like Hakainde Hichilema diligence. -

Zambia Page 1 of 8

Zambia Page 1 of 8 Zambia Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2003 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 25, 2004 Zambia is a republic governed by a president and a unicameral national assembly. Since 1991, multiparty elections have resulted in the victory of the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD). MMD candidate Levy Mwanawasa was elected President in 2001, and the MMD won 69 out of 150 elected seats in the National Assembly. Domestic and international observer groups noted general transparency during the voting; however, they criticized several irregularities. Opposition parties challenged the election results in court, and court proceedings were ongoing at year's end. The anti-corruption campaign launched in 2002 continued during the year and resulted in the removal of Vice President Kavindele and the arrest of former President Chiluba and many of his supporters. The Constitution mandates an independent judiciary, and the Government generally respected this provision; however, the judicial system was hampered by lack of resources, inefficiency, and reports of possible corruption. The police, divided into regular and paramilitary units under the Ministry of Home Affairs, have primary responsibility for maintaining law and order. The Zambia Security and Intelligence Service (ZSIS), under the Office of the President, is responsible for intelligence and internal security. Civilian authorities maintained effective control of the security forces. Members of the security forces committed numerous serious human rights abuses. Approximately 60 percent of the labor force worked in agriculture, although agriculture contributed only 15 percent to the gross domestic product. Economic growth increased to 4 percent for the year. -

Post-Populism in Zambia: Michael Sata's Rise

This is the accepted version of the article which is published by Sage in International Political Science Review, Volume: 38 issue: 4, page(s): 456-472 available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512117720809 Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/24592/ Post-populism in Zambia: Michael Sata’s rise, demise and legacy Alastair Fraser SOAS University of London, UK Abstract Models explaining populism as a policy response to the interests of the urban poor struggle to understand the instability of populist mobilisations. A focus on political theatre is more helpful. This article extends the debate on populist performance, showing how populists typically do not produce rehearsed performances to passive audiences. In drawing ‘the people’ on stage they are forced to improvise. As a result, populist performances are rarely sustained. The article describes the Zambian Patriotic Front’s (PF) theatrical insurrection in 2006 and its evolution over the next decade. The PF’s populist aspect had faded by 2008 and gradually disappeared in parallel with its leader Michael Sata’s ill-health and eventual death in 2014. The party was nonetheless electorally successful. The article accounts for this evolution and describes a ‘post-populist’ legacy featuring hyper- partisanship, violence and authoritarianism. Intolerance was justified in the populist moment as a reflection of anger at inequality; it now floats free of any programme. Keywords Elections, populism, political theatre, Laclau, Zambia, Sata, Patriotic Front Introduction This article both contributes to the thin theoretic literature on ‘post-populism’ and develops an illustrative case. It discusses the explosive arrival of the Patriotic Front (PF) on the Zambian electoral scene in 2006 and the party’s subsequent evolution. -

Intra-Party Democracy in the Zambian Polity1

John Bwalya, Owen B. Sichone: REFRACTORY FRONTIER: INTRA-PARTY … REFRACTORY FRONTIER: INTRA-PARTY DEMOCRACY IN THE ZAMBIAN POLITY1 John Bwalya Owen B. Sichone Abstract: Despite the important role that intra-party democracy plays in democratic consolidation, particularly in third-wave democracies, it has not received as much attention as inter-party democracy. Based on the Zambian polity, this article uses the concept of selectocracy to explain why, to a large extent, intra-party democracy has remained a refractory frontier. Two traits of intra-party democracy are examined: leadership transitions at party president-level and the selection of political party members for key leadership positions. The present study of four political parties: United National Independence Party (UNIP), Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD), United Party for National Development (UPND) and Patriotic Front (PF) demonstrates that the iron law of oligarchy predominates leadership transitions and selection. Within this milieu, intertwined but fluid factors, inimical to democratic consolidation but underpinning selectocracy, are explained. Keywords: Intra-party Democracy, Leadership Transition, Ethnicity, Selectocracy, Third Wave Democracies Introduction Although there is a general consensus that political parties are essential to liberal democracy (Teorell 1999; Matlosa 2007; Randall 2007; Omotola 2010; Ennser-Jedenastik and Müller 2015), they often failed to live up to the expected democratic values such as sustaining intra-party democracy (Rakner and Svasånd 2013). As a result, some scholars have noted that parties may therefore not necessarily be good for democratic consolidation because they promote private economic interests, which are inimical to democracy and state building (Aaron 1 The authors gratefully acknowledge the comments from the editorial staff and anonymous reviewers. -

C:\Users\Public\Documents\GP JOBS\Gazette\Gazette 2017

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA Price: K10.00 net Annual Subscription: Within Lusaka—K300.00 Published by Authority Outside Lusaka—K350.00 No. 6584] Lusaka, Friday, 30th June, 2017 [Vol. LIII, No. 42 TABLE OF CONTENTS GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 426 OF 2017 [7523640 Gazette Notices No. Page The Lands and Deeds Registry Act (Chapter 185 of the Laws of Zambia) Lands and Deeds Registry Act: (Section 56) Notice of Intention to Issue Duplicate Document 425 499 Notice of Intention to Issue Duplicate Document 426 499 Notice of Intention to Issue Duplicate Document 427 499 Notice of Intention to Issue a Duplicate Certificate of Title Companies Act: FOURTEEN DAYS after the publication of this notice I intend to issue Notice Under Section 361 428 449 a Certificate of Title No. 77433 in the name of Shengebu Stanley Notice Under Section 361 429 500 Shengebu in respect of Stand No. LUS/30340 in extent of 0.5907 Notice Under Section 361 430 500 hectares situate in the Lusaka Province of the Republic of Zambia. Notice Under Section 361 431 500 Notice Under Section 361 432 500 All persons having objections to the issuance of the duplicate Notice Under Section 361 433 500 certificate of title are hereby required to lodge the same in writing Notice Under Section 361 434 501 with the Registrar of Lands and Deeds within fourteen days from Notice Under Section 361 435 501 the date of publication of this notice. Notice Under Section 361 436 501 E. TEMBO, Notice Under Section 361 437 501 REGISTRY OF LANDS AND DEEDS Registrar Notice Under Section 361 438 501 Notice Under Section 361 439 501 P.O. -

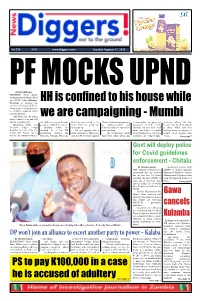

HH Is Confined to His House While We Are Campaigning

No 750 K10 www.diggers.news Tuesday Auguest 11, 2020 PFBy Julia Malunga MOCKS UPND PATRIOTIC Front deputy secretary general Mumbi Phiri says UPND leader Hakainde Hichilema is enjoying the HH is confined to his house while comfort of his house while the ruling party is campaigning so he shouldn’t complain when he loses elections. And Phiri says the ruling we are campaigning - Mumbi party is here to stay and will rule for over 100 years. the Makeni overpass because Hichilema was seated in his Davies Mwila was campaigning I congratulate my party for Continue talking like that Meanwhile, Phiri says people are difficult to control. house while her party was in Mwansabombwe and winning 10 out of the 15 by- because you think everybody President Edgar Lungu Speaking when she campaigning. Lukashya when the opposition elections we just had. And is cheap. When you start shouldn’t be blamed for the featured on a Joy FM She was agreeing with a were watching. when you listen to people looking down on people ati crowd that turned up to programme dubbed Thecaller identified as Diana who “The by-elections which down playing this to say ‘those abantu (those people) who witness the commissioning of Platform, Monday, Phiri said said the PF secretary general have been talked about and councilors are being bought’. voted...” Story page 7 Govt will deploy police for Covid guidelines enforcement - Chitalu By Natasha Sakala Speaking during the daily THE Ministry of Health has COVID-19 update, Monday, announced that the country Minister of Health Dr Chitalu has in the last 24 hours Chilufya said 104 persons had recorded 125 new COVID-19 been discharged in the last 24 cases out of 454 tests done hours.