Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EVAIR Safety Bulletin No 4

Cooperative Network Design EVAIR Safety Bulletin No 4 Summer Seasons 2006-2009 Evolution EUROCONTROL EVAIR_bulletin04.indd 1 15/02/10 14:15 EUROCONTROL VOLUNTARY ATM INCIDENT Data providers REPORTING (EVAIR) The number of EVAIR ATM incident data providers among commer- cial airlines has been increasing year on year. By the end of 2009, 63 SUMMER SEASONS 2006-2009 EVOLUTION airlines were providing ATM incident reports to EVAIR. The airlines which contribute to EVAIR account for 50% of the overall European EXECUTIVE SUMMARY air traffic. The statistics in the EVAIR Safety Bulletin No 4 cover the summer Main trends periods (April - September) 2006 to 2009. The statistics are based Eight main ATM contributors are used as the basis for monitoring: on the ATM/CNS incident reports collected manually and ACAS RAs collected automatically from one Mode-S radar station. The 1. Mistakes; main data providers are commercial airlines and ANSPs providing 2. Spoken Communication; feedback to airlines’ incident reports and the ACAS RAs from the 3. Operational Communication; Mode-S radar station. 4. Traffic and Airspace problems; 5. Traffic Information; Data collection 6. Lapses; Through the manual data provision (commercial airlines and feed- 7. ATC Clearance; back from ANSPs) EVAIR collected approximately 1500 reports for 8. Coordination. the summer seasons from 2006 to 2009. For the same period, 2637 valid ACAS RAs were collected automatically from the Mode S radar During the summer periods 2006-2009 in absolute figures, Mistakes station. with 27%, Spoken communication with 19%, Operational Communi- cation and Traffic information with 11% each make almost 70% of the The number of reports EVAIR collects has grown each year. -

TED STEVENS ANCHORAGE INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT Anchorage, Alaska

TED STEVENS ANCHORAGE INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT Anchorage, Alaska PFC Quarterly Report - Receipts Collected For the Quarter Ended March 31,2009 (Application No. 1 ) Application #99-01-C-00-ANC & 99-01-C-01-ANC $22,000,000.00 0.00 Total Collection Authority $22,000,000.00 PFC Revenue Received Air Carriers Current Quarter Previous Quarters Cumulative Aces Airlines 32.12 32.12 Aer Lingus 317.44 317.44 Aerovias De Mexico 122.58 122.58 Aero Mexico 98.53 98.53 Air Canada 136,476.21 136,476.21 Air France 1,764.99 1,764.99 Air New Zealand 2,094.33 2,094.33 Air Pacific 8.67 8.67 Airlines Services Corporation 37.96 37.96 Air Wisconsin Airlines 46.54 46.54 Alaska Airlines 11,024,874.06 11,024,874.06 Alitalia Airlines 1,051.51 1,051.51 All Nippon Airways Co 1,905.64 1,905.64 Aloha Airlines 7,152.82 7,152.82 America Central Corp 23.36 23.36 America West Airlines 228,474.04 228,474.04 American Airlines 509,508.22 509,508.22 American Trans Air 6,513.14 6,513.14 Asiana Airlines 2,125.95 2,125.95 Atlantic Coast Airline 96.36 96.36 Avianca 8.76 8.76 Big Sky Airlines 87.36 87.36 British Airways 12,272.36 12,272.36 Canada 3000 10,999.72 10,999.72 Cathay Pacific Airways 271.27 271.27 China Airlines 78,473.09 78,473.09 Condor Flugdienst, GMBH 63,889.95 63,889.95 Continental Airlines 1,380,859.31 1,380,859.31 Czech Airlines 348.36 348.36 Delta Airlines 1,673,182.33 1,673,182.33 Elal Israel Airlines 110.74 110.74 Emirates 14.57 14.57 Era Aviation, Inc. -

Abelag Aviation Aigle Azur Transports Aeriens Air

COMITÉ DE COORDINATION DES AÉROPORTS FRANÇAIS FRENCH AIRPORTS COORDINATION COMMITTEE Membres au 1er septembre 2016 Members on September 1st 2016 Transporteurs aériens - Air carriers : AAF ABELAG AVIATION AAL AIGLE AZUR TRANSPORTS AERIENS AAR AIR ATLANTIQUE ABW AMERICAN AIRLINES ACA AMSTERDAM AIRLINES ADR ASIANA AIRLINES AEA AFRIQIYAH AIRWAYS AEE AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC AFL AIR CONTRACTORS LTD AFR AIRBRIDGE CARGO AHY ABX AIR AIC AIR ARABIA AIZ AIR CANADA ALK AIR ORIENT AMC ITALI AIRLINES AMX ANTONOV AIRLINES ANA AIR ONE ANE ALYZIA ASSISTANCE ADP ASL ADRIA AIRWAYS AUA AIR EUROPA AUI AEGEAN AIRLINES AZA AIR ITALY POLSKA BAW STEVE TEST TO KEEP BCS ASTRAEUS BEE AEROSVIT AIRLINES BEL AIR ITALY BER AIR FRANCE HANDLING BIE AEROFLOT RUSSIAN AIRLINES BMR AIR FRANCE BMS AZERBAIJAN AIRLINES BOS AVIES BRU AIRBUS INDUSTRIE BTI AIR INDIA CAI AIR GABON INTERNATIONAL CAJ ARKIA ISRAELI AIRLINES CCA YAK SERVICE AIRLINES CCM SRILANKAN AIRLINES CES HEWA BORA CFE ALYSAIR aviation generale CHH AIR MALTA CLG AMERICAN TRANSAIR CPA AMC AVIATION CRC AEROMEXICO CRL ALL NIPPON AIRWAYS CSA AIR NOSTRUM CSN AIR NIGERIA CTN YANAIR CUB AIR NEW ZEALAND DAH AEOLIAN AIRLINES DAL CODE ASSISTANT AVIAPARTNER DJT ARIK INTERNATIONAL DLH ATA AEROCONDOR DTH AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS EIN AIR ARMENIA ELL SMARTLYNX ITALIA ELY ARAVCO LTD ETD AirSERBIA ETH AVANTI AIR EVA AUSTRIAN AIRLINES EWG AUGSBURG AIRWAYS EZE UKRAINE INTL AIRLINES EZS AURIGNY AIR SERVICES EZY TITAN AIRWAYS FDX US AIRWAYS FHY AIR INDIA EXPRESS FIN AIR EXPLORE FPO ATLANT-SOYUZ FWI ALITALIA GFA ARCUS AIR GMI ASTRA AIRLINES -

Economic Importance of Air Transport and Airport Activities in Belgium – Report 2009

Economic Importance of Air Transport and Airport Activities in Belgium – Report 2009 Working Paper Document by Xavier Deville and Saskia Vennix December 2011 No 218 Editorial Director Jan Smets, Member of the Board of Directors of the National Bank of Belgium Statement of purpose: The purpose of these working papers is to promote the circulation of research results (Research Series) and analytical studies (Documents Series) made within the National Bank of Belgium or presented by external economists in seminars, conferences and conventions organised by the Bank. The aim is therefore to provide a platform for discussion. The opinions expressed are strictly those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bank of Belgium. Orders For orders and information on subscriptions and reductions: National Bank of Belgium, Documentation - Publications service, boulevard de Berlaimont 14, 1000 Brussels Tel +32 2 221 20 33 - Fax +32 2 21 30 42 The Working Papers are available on the website of the Bank: http://www.nbb.be © National Bank of Belgium, Brussels All rights reserved. Reproduction for educational and non-commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged. ISSN: 1375-680X (print) ISSN: 1784-2476 (online) NBB WORKING PAPER No. 218 - DECEMBER 2011 ABSTRACT This study assesses the economic importance of air transport and airport activities in Belgium in terms of employment, value added and investment over the period 2007 - 20091. The sector considered embraces not only the activities directly connected with air transport, but also all the activities which take place on site at the six Belgian airports (Antwerp, Brussels, Charleroi, Kortrijk, Liège, Ostend). -

Hubert Horan 3:00 - 5:00 Pm

Transportation Center Icarus Society presents…… “Economics of Airline Industry Consolidation” Speaker: Thurs. May 17, 2012 Hubert Horan 3:00 - 5:00 pm Aviation Expert and Independent Location: The Transportation Center Chambers Hall _ Lower Level Airline Consultant 600 Foster, Evanston Hubert Horan will provide insights into the future of the airline industry with special focus on alliances, metal neutrality and airlines mergers – now and in the future – drawing on his extensive expertise and experience in the aviation industry. Bio: Hubert Horan’s 25 year aviation career has been evenly split between consulting and airline management positions. He has been directly involved with multiple waves of airline mergers, alliances and industry restructuring, and since 2002 has been an independent consultant based in Phoenix. He has been directly involved with most of the major changes in international aviation since deregulation. In the 1980s he developed the original plan for the TWA-Ozark merger and also participated in the USAir– Piedmont and Continental-People Express mergers. He worked on a series of projects with Lufthansa and Alitalia to help them prepare for liberalization within Europe, and prepared the original plan for a Qantas- Australian-Air New Zealand merger. While at Northwest he led a massive international route network restructuring that drove the airline’s late 90s financial turnaround. He was responsible for the original development of the KLM-Northwest alliance network that served as the template for all subsequent immunized alliances. He spent four years in Zurich grappling with Swissair-Sabena, Europe’s first cross-border merger, and Swissair’s alliances with Delta and American. -

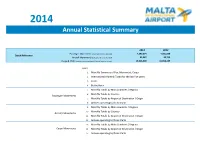

Annual Statistical Summary

2014 Annual Statistical Summary 2014 2013 Passenger Movements (Scheduled & non-Scheduled) 4,290,304 4,031,500 Quick Reference Aircraft Movements (Scheduled & non-Scheduled) 32,247 30,752 Cargo & Mail (Scheduled, non-Scheduled & General Aviation), in kilos 15,546,540 16,038,449 report 1 Monthly Summary of Pax, Movement, Cargo 2 International Monthly Totals for the last five years 3 Peaks 4 By the Hour 5 Monthly Totals by Main Countries / Regions 6 Monthly Totals by Country Passenger Movements 7 Monthly Totals by Airport of Destination / Origin 8 Airlines operating to/from Malta 9 Monthly Totals by Main Countries / Regions 10 Monthly Totals by Country Aircraft Movements 11 Monthly Totals by Airport of Destination / Origin 12 Airlines operating to/from Malta 13 Monthly Totals by Main Countries / Regions Cargo Movements 14 Monthly Totals by Airport of Destination / Origin 15 Airlines operating to/from Malta report 1 Monthly Summary of Pax, Movement, Cargo Passenger Movements Scheduled & Non-Scheduled Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Total 2014 Total 2013 Arrivals 98,786 99,898 133,999 195,325 204,260 215,227 263,103 265,333 230,289 205,139 120,718 112,116 2,144,193 2,016,196 Departures 100,568 93,432 129,534 181,610 197,991 209,102 248,308 286,117 232,926 216,584 135,543 114,396 2,146,111 2,015,304 Total [Scheduled & Non- Scheduled] 199,354 193,330 263,533 376,935 402,251 424,329 511,411 551,450 463,215 421,723 256,261 226,512 4,290,304 4,031,500 Transit [counted only on 22,314 departure] 3,319 3,147 3,757 3,084 3,101 2,875 -

1.4. Coding and Decoding of Airlines 1.4.1. Coding Of

1.4. CODING AND DECODING OF AIRLINES 1.4.1. CODING OF AIRLINES In addition to the airlines' full names in alphabetical order the list below also contains: - Column 1: the airlines' prefix numbers (Cargo) - Column 2: the airlines' 2 character designators - Column 3: the airlines' 3 letter designators A Explanation of symbols: + IATA Member & IATA Associate Member * controlled duplication # Party to the IATA Standard Interline Traffic Agreement (see section 8.1.1.) © Cargo carrier only Full name of carrier 1 2 3 40-Mile Air, Ltd. Q5 MLA AAA - Air Alps Aviation A6 LPV AB Varmlandsflyg T9 ABX Air, Inc. © 832 GB Ada Air + 121 ZY ADE Adria Airways + # 165 JP ADR Aegean Airlines S.A. + # 390 A3 AEE Aer Arann Express (Comharbairt Gaillimh Teo) 809 RE REA Aeris SH AIS Aer Lingus Limited + # 053 EI EIN Aero Airlines A.S. 350 EE Aero Asia International Ltd. + # 532 E4 Aero Benin S.A. EM Aero California + 078 JR SER Aero-Charter 187 DW UCR Aero Continente 929 N6 ACQ Aero Continente Dominicana 9D Aero Express Del Ecuador - Trans AM © 144 7T Aero Honduras S.A. d/b/a/ Sol Air 4S Aero Lineas Sosa P4 Aero Lloyd Flugreisen GmbH & Co. YP AEF Aero Republica S.A. 845 P5 RPB Aero Zambia + # 509 Z9 Aero-Condor S.A. Q6 Aero Contractors Company of Nigeria Ltd. AJ NIG Aero-Service BF Aerocaribe 723 QA CBE Aerocaribbean S.A. 164 7L CRN Aerocontinente Chile S.A. C7 Aeroejecutivo S.A. de C.V. 456 SX AJO Aeroflot Russian Airlines + # 555 SU AFL Aeroflot-Don 733 D9 DNV Aerofreight Airlines JSC RS Aeroline GmbH 7E AWU Aerolineas Argentinas + # 044 AR ARG Aerolineas Centrales de Colombia (ACES) + 137 VX AES Aerolineas de Baleares AeBal 059 DF ABH Aerolineas Dominicanas S.A. -

Improving Air Cargo Through Data Intelligence Supply Chain Conference - Big Data in Logistics

Click to edit title. IMPROVING AIR CARGO THROUGH DATA INTELLIGENCE SUPPLY CHAIN CONFERENCE - BIG DATA IN LOGISTICS Alban FRANCOIS – Vice President Cargo Brussels – 22 Nov 16 ClickBrussels to Airlines edit in atitle. nutshell Key numbers Key dates 49 95 Destinations • Creation of SN Brussels Airlines following 2002 Sabena bankruptcy Aircraft 3.500 19 2005-2006 • Merger Virgin Express – SN Brussels Direct jobs >40.000 Africa hub Airlines to become Brussels Airlines Tonnage 7,5 • Entry of Lufthansa in capital (45%) >10.000 €1,27 bn Mio 2009 • Entry into Star Alliance Indirect jobs Passengers Turnover Shareholding structure 2012 • Heavy restructuring (Plan Beyond 12/13) • Continuous transformation of the 2013-2016 company to build a new “no comprise” business model Click2014 – 2016:to editBuilding title. a new Brussels Airlines New set of products adapted Focus on loyalty Focus on our guests to guest needs Development of partnerships Investments in service & tools All translated in modern building on the Belgian touch brand Click to edit title.ON THE ROAD TO OUR 2018 AMBITION… 2013 2014 2015 2018 Revenue €1.1 bn €1.2 bn €1.27 bn €1.5 bn Guests 5.9 Mio 6.7 Mio > 7 Mio 10 Mio … SOF 67.4% 71.9% 75.4% 80% Profit - €22Mio - €4 Mio €41.3 Mio >€50Mio Click to edit title. BRUSSELS AIRLINES CARGO MISSION STATEMENT WE GO THE EXTRA SMILE. We want to be the preferred air cargo provider across our network, known for its reliable service & flexibility. Going beyond filling our bellies, we focus on delivering the right solution to our customers. -

Air Transport Industry

ANALYSIS OF THE EU AIR TRANSPORT INDUSTRY Final Report 2004 Contract no: TREN/05/MD/S07.52077 By Cranfield University CONTENTS GLOSSARY...........................................................................................................................................................6 1. AIR TRANSPORT INDUSTRY OVERVIEW ..................................................................................12 2. REGULATORY DEVELOPMENTS .................................................................................................18 3. CAPACITY ...........................................................................................................................................24 4. AIR TRAFFIC ......................................................................................................................................36 5. AIRLINE FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE .......................................................................................54 6. AIRPORTS............................................................................................................................................86 7. AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL ...............................................................................................................104 8. THE ENVIRONMENT......................................................................................................................114 9. CONSUMER ISSUES ........................................................................................................................118 10 AIRLINE ALLIANCES.....................................................................................................................126 -

British Airways Profile

SECTION 2 - BRITISH AIRWAYS PROFILE OVERVIEW British Airways is the world's second biggest international airline, carrying more than 28 million passengers from one country to another. Also, one of the world’s longest established airlines, it has always been regarded as an industry-leader. The airline’s two main operating bases are London’s two main airports, Heathrow (the world’s biggest international airport) and Gatwick. Last year, more than 34 million people chose to fly on flights operated by British Airways. While British Airways is the world’s second largest international airline, because its US competitors carry so many passengers on domestic flights, it is the fifth biggest in overall passenger carryings (in terms of revenue passenger kilometres). During 2001/02 revenue passenger kilometres for the Group fell by 13.7 per cent, against a capacity decrease of 9.3 per cent (measured in available tonne kilometres). This resulted in Group passenger load factor of 70.4 per cent, down from 71.4 per cent the previous year. The airline also carried more than 750 tonnes of cargo last year (down 17.4 per cent on the previous year). The significant drop in both passengers and cargo carried was a reflection of the difficult trading conditions resulting from the weakening of the global economy, the impact of the foot and mouth epidemic in the UK and effects of the September 11th US terrorist attacks. An average of 61,460 staff were employed by the Group world-wide in 2001-2002, 81.0 per cent of them based in the UK. -

Impact of Airline Consolidation on Consumer Choice

Impact of Airline Consolidation on Consumer Choice The role of indirect distribution channels in ensuring price transparency and promoting competition Supported by: Prepared by: 11 Octob er 2017 Impact of Airline Consolidation on the Indirect Distribution Channel 2 Contents 1 — Executive Summary 3 2 — Recommendations 8 3 — Evolution of the Airline Industry and Implications for Policy 9 // US DOT and Europe’s DG-COMP perspective on airline competition 9 // European market liberalization and transformation of business models 13 // Airline liberalization and consumer benefits 20 // Economics literature regarding airline consolidation 22 // Evidence from the more consolidated U.S. market 46 // Conclusions 48 // Implications for DG-COMP and DG-MOVE policy going forward 49 4 — References 52 5 — List of Exhibits // Exhibit 1: EU Competition Review Process 11 // Exhibit 2: Consolidation of the Full Service Carriers 15 // Exhibit 3: ICAO Listing of European LLC’s 17 // Exhibit 4: Market Shares of Seats and HHI in the Intra-EU Market 19 // Exhibit 5: Foreclosing a Spoke City 23 // Exhibit 6: Case Study of LH-OS Slot Divestitures 24 // Exhibit 7: ATI /JV Alliances Potentially Affect Competition on All Routes at a Hub 25 // Exhibit 8: The Negative Impact of Market Structure on Fares in Connecting Markets 26 // Exhibit 9: U.S. Carrier Transatlantic Operating Margin vs. HHI 31 // Exhibit 10: U.S. Carrier Domestic Operating Margin and Seat Growth 33 // Exhibit 11: Normal Google Results 40 // Exhibit 12: Google Results with Google Flights (GFS) 40 // Exhibit 13: Effectiveness of Slot Remedies in EU Short Haul Markets 50 Impact of Airline Consolidation on the Indirect Distribution Channel 3 1 — Executive Summary 1. -

Accessible Travel in Flanders and Brussels

Accessible travel in Flanders and Brussels Last amended: January 2012 Accessible Travel Info Point – Tourism Flanders Grasmarkt 61, 1000 Brussels +32 70 23 30 50 - +32 70 23 30 51 www.accessinfo.be - [email protected] 1 Introduction This information leaflet gives an overview of accessible transport in and from Flanders and Brussels. Whether something is considered accessible depends largely on the person concerned. Each disability or impairments is different. We recommend you to contact the transport company in advance in order to obtain concrete information relating to your own expectations. Table of contents Public transport p3 NMBS (train) p3 De Lijn (bus and tram) in Flanders p4 MIVB (metro, bus and tram) in Brussels p6 Private transport p8 Bus companies with lift bus p8 Wheelchair taxi's p 10 Adapted transport services p13 Travelling by plane p17 Motor homes p22 2 Public transport NMBS (train) Guide for passengers with reduced mobility Belgian Railways (NMBS-SNCB) publishes a brochure with information about services for people with reduced mobility and this contains a detailed list of stations and facilities for people with reduced mobility. The brochure is available in Dutch, French, German and English in the stations or on their website: www.b-rail.be/nat/E/assets/basea5_ang_04web.pdf (for the English language version). The brochure is also available in Braille. To receive this brochure in Braille, please send an e-mail to: [email protected]. For further information on travelling by train for the disabled, you can also visit the following website: website www.b-rail.be > Belgium > Useful Tips > Assistance for passengers with reduced mobility.