Using Genome-Wide Snps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Following the Finke: a Modern Expedition Down the River of Time

FOLLOWING THE FINKE FOLLOWING THE FINKE: A MODERN EXPEDITION DOWN THE RIVER OF TIME PART I: TRAVERSING AN ANCIENT LAND DR KATE LEEMING HOPS ON HER CUSTOM-MADE BIKE TO TAKE ON THE AUSTRALIAN INTERIOR. WORDS AND PICS: KATE LEEMING Back in 2004, during my 25,000km Great for the local Aboriginal people and wildlife, unpredictable surfaces requires a similar skill Australian Cycle Expedition (GRACE), in the present day and for eons past. If Uluru set to pedalling over snow. My ‘Following the cycling companion Greg Yeoman and symbolises the nation’s heart, then the Finke Finke River’ expedition therefore would double I camped beside the Finke River near to River, or Larapinta as it is known to the local as a credible expedition in its own right and where it intersects with the Stuart Highway. Arrernte, must surely be its ancient artery. as excellent physical and mental training for We were on our way to Uluru and beyond This is where the germ of my idea to travel cycling across Antarctica. and the Finke River crossing was at the end the course of the Finke River evolved, however The Finke originates about 130km west of of our first day’s ride south of Alice Springs. the concept of biking along the sandy and Alice Springs in the West MacDonnell Ranges, I’d aimed to reach this point because I stony bed of the ephemeral river at that time the remnants of an ancient system of fold wanted to experience camping beside was an impossibility. A decade later, the mountains that was once on the scale of the what is commonly referred to as the world’s development of fatbike technology began Himalayas, but has now diminished to be a oldest river. -

ACT Flood Watch Areas

! ! ! ! Barkly Warrego Flood Watch Area No. ! Homestead Ayr ! ! Tennant Roadhouse Angas and Brem!er Rivers 28 Flood Watch Areas ! Home Balgo Creek Camooweal Charters ! Broughton RivHeirll 19 ! Hill !Towers South Australia ! Cooper Creek Bowen 7 ! Mount Julia Danggali Rivers and CCreolelinkssville Prose1rp7ine Creek ! NT Isa Cloncurry ! ! ! Diamantina River 3 !Hughenden Eastern Eyre Peninsula 18 Stamford MACKAY " Telfer ! Eastern Great Victoria Desert 9 ! Sarina ! Finke River and Stephenson Creek 5 Fleurieu Peninsula 29 !Moranbah Flinders Ranges Rivers Cotton Yuendumu 1 ! Winton 15 Creek ! and Creeks ! Dysart Gawler River ! 24 Clermont Boulia ! ! Georgina River and Eyre Creek 1 Papunya ! Kangaroo Island 30 !Longreach Alice Lake Eyre !Emerald 10 Springs !Alpha WA ! 2 Lake Frome 11 Hermannsburg ! Santa 3 Lake Gairdner Springsure 12 !Teresa ! Light and Wakefield Rivers 21 Docker River QLD Limestone and (Kaltukatjara) 31 ! M!iTllaicmebnot Coast Rivers and Creeks Erldunda Lower Eyre Peninsula 22 ! ! Yulara Tourist Village 4 Windorah ! North West Lake Torrens 14 ! Carnegie NullarbAougr aDthiesltlarict Rivers 13 ! Birdsville ! ! Onkaparinga River 27 Warburton! ! River Murray Murraylands 26 Amata 5 Charleville ! Mitchell River Murray Riverlands! Rom20a !Quilpie ! Simpson Desert 4 Tjukayirla 6 Roadhouse Torrens and metropolitan rivers Surat ! 2!5 and creeks ! 7 Warburton District Rivers 6 Innamincka Oodnadatta 8 ! Warburton River 8 !Thargomindah St George West Coast Rivers and Creeks ! 16 Ilkurlka ! 9 Western Desert 2 Dirranbandi !Laverton ! Coober -

Report to Office of Water Science, Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation, Brisbane

Lake Eyre Basin Springs Assessment Project Hydrogeology, cultural history and biological values of springs in the Barcaldine, Springvale and Flinders River supergroups, Galilee Basin and Tertiary springs of western Queensland 2016 Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation Prepared by R.J. Fensham, J.L. Silcock, B. Laffineur, H.J. MacDermott Queensland Herbarium Science Delivery Division Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation PO Box 5078 Brisbane QLD 4001 © The Commonwealth of Australia 2016 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence Under this licence you are free, without having to seek permission from DSITI or the Commonwealth, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the source of the publication. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5725 Citation Fensham, R.J., Silcock, J.L., Laffineur, B., MacDermott, H.J. -

Grey Thrush Feeding Young. Photo, by A

Grey Thrush feeding young. Photo, by A. D. Selby, R.A.O.U. Chlamydera nuchalis. Great Bower Bird.—Several were seen at our first camp on the Gregory River where they came to water at a stony crossing. At Gregory Downs we were told that they were a nuisance in the vegetable gardens, pulling up and eating the young plants, and that in consequence four had been shot on the previous day. Mr. Watson guided us to a bower placed in the centre of a clump of currant bushes, about a mile from the house in open forest country. A bird was seen to leave the bower as we approached it. The bower was very compactly built and decorated at either end with a litter of shells and pebbles. Corvus coronoides. Australian Raven.—Ravens were seen on the Gregory, fully one hundred; with an equal number of Black Kites and a few Whistling Eagles; all were disturbed from a dead bullock. They came about our camp on the Gregory and were the earliest at any carcase. The Whistling Eagles, however, disputed possession but the Ravens obtained their share by stealth. On the Leichhardt River Ravens were seen. C. bennettii. Little Crow.—After South Queensland this bird was seen only near Headingly Station on the Georgina River. Corcorax melanorhamphus. White-winged Chough.—Numbers seen at a camp on the Nive River, where a nest was being built by a party of them. Cracticus nigrogularis. Pied Butcher Bird. — These fine birds were first seen at the Long Waterhole on the Wilson River; afterwards they were met with on Kyabra Creek, and, after the dry stretch from Win- dorah we did not see them until the hilly country near Dajarra. -

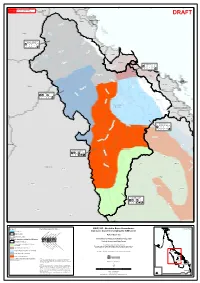

GWQ1203 - Burdekin Basin Groundwater Location Map Watercourse Cainozoic Deposits Overlying the GAB Zones

144°0'0"E 145°0'0"E 146°0'0"E 147°0'0"E 148°0'0"E 149°0'0"E Tully 18°0'0"S This map must not be used for marine navigation. 18°0'0"S Comprehensive and updated navigation WARNING information should be obtained from published Mitchell hydrographic charts. Murray DRAFT Hinchinbrook Island Herbert r ve Ri ekin urd B Ingham ! er iv D R ry Gilbert ry Ri D v er r e iv 19°0'0"S Scattered Remnants Northern R 19°0'0"S g Burdekin Headwaters in n n R u Black Townsville ! er r iv e R v rke i la R C r ta S Ross Broken River Ayr ! er ver Riv i ry lt R Haughton go Basa e r Don and Bogie Coastal Area G h t r u ve o i ton R S h ug Ha Bowen ! 20°0'0"S 20°0'0"S r Charters Towers e v ! i Don R B n o o g i D e Riv er Bur dek in R ive r Whitsunday Island Proserpine B owe Proserpine Flinders n ! er R Riv iver e sp a R amp C o Don River l l s to n R iv C e a r North West Suttor Catchment pe R r iv ve e i r R r o t t u S r e Broken v R i iv S e R e r llh L e e i O'Connell p im t t a l R e C iv er B o w e B u r d ekin n B u r d ekin R 21°0'0"S i 21°0'0"S v e BB a a s s in in r B ro Mackay ke ! n River Pioneer Plane Sarina ! Eastern Weathered Su ttor R Cainozoic Remnants Belyandor River iv e er iv R o d n lya e B r e v i R o d Moranbah n ! a ly 22°0'0"S e 22°0'0"S l R B ae iver ich Carm r ive R Diamantina s r o n n o C Styx Belyando River Saline Tertiary Sediments Dysart ! Is a a c R iv B Clermont Middlemount er e ! ! l y an do Riv e r er iv Cooper Creek R ie nz Aramac e ! k c a M 23°0'0"S 23°0'0"S Capella -

Innamincka/Cooper Creek State Heritage Area Innamincka/Cooper Creek Was Declared a State Heritage Area on 16 May 1985

Innamincka/Cooper Creek State Heritage Area Innamincka/Cooper Creek was declared a State Heritage Area on 16 May 1985. HISTORY Innamincka and Cooper Creek have a rich history. The area has also been associated with many other facets of the state's history since colonial settlement. Names such as Charles Sturt, Sidney Kidman, Cordillo Downs, the Australian Inland Mission and the Reverend John Flynn are intrinsically woven into the stories of Innamincka and the Cooper Creek. Its significance for Aboriginal people spans thousands of years as a trade route and a source of abundant food and fresh water. The area's Aboriginal history also includes significant contacts with explorers, pastoralists and settlers. Many sources believe that the name 'Innamincka' comes from two Aboriginal words meaning ' your shelter' or 'your home'. European contact with the region came first with the explorers and later with the establishment of the pastoral industry, transport routes and service centres. Cooper Creek was named by Captain Charles Sturt on 13 October 1845, when he crossed the watercourse at a point approximately 24 kilometres west of the current Innamincka township. The water was very low at the time, hence his use of the term 'creek' rather than 'river' to describe what often becomes a deep torrent of water. Charles Cooper, after whom the waterway was named, was a South Australian judge - later Chief Justice Sir Charles Cooper. On the same expedition, Sturt also named the Strzelecki Desert after the eccentric Polish explorer, Paul Edmund de Strzelecki, who was the first European to climb and name Mount Kosciusko. -

100 the SOUTH-WEST CORNER of QUEENSLAND. (By S

100 THE SOUTH-WEST CORNER OF QUEENSLAND. (By S. E. PEARSON). (Read at a meeting of the Historical Society of Queensland, August 27, 1937). On a clear day, looking westward across the channels of the Mulligan River from the gravelly tableland behind Annandale Homestead, in south western Queensland, one may discern a long low line of drift-top sandhills. Round more than half the skyline the rim of earth may be likened to the ocean. There is no break in any part of the horizon; not a landmark, not a tree. Should anyone chance to stand on those gravelly rises when the sun was peeping above the eastem skyline they would witness a scene that would carry the mind at once to the far-flung horizons of the Sahara. In the sunrise that western region is overhung by rose-tinted haze, and in the valleys lie the purple shadows that are peculiar to the waste places of the earth. Those naked, drift- top sanddunes beyond the Mulligan mark the limit of human occupation. Washed crimson by the rising sun they are set Kke gleaming fangs in the desert's jaws. The Explorers. The first white men to penetrate that line of sand- dunes, in south-western Queensland, were Captain Charles Sturt and his party, in September, 1845. They had crossed the stony country that lies between the Cooper and the Diamantina—afterwards known as Sturt's Stony Desert; and afterwards, by the way, occupied in 1880, as fair cattle-grazing country, by the Broad brothers of Sydney (Andrew and James) under the run name of Goyder's Lagoon—and the ex plorers actually crossed the latter watercourse with out knowing it to be a river, for in that vicinity Sturt describes it as "a great earthy plain." For forty miles one meets with black, sundried soil and dismal wilted polygonum bushes in a dry season, and forty miles of hock-deep mud, water, and flowering swamp-plants in a wet one. -

Warrego River Scoping Study – Summary

FinalWestern Summary Catchment Management Authority WarregoFinal River Summary Scoping Study 2008 WESTERN Contact Details Western CMA Offices: 45 Wingewarra Street Dubbo NSW 2830 Ph 02 6883 3000 32 Sulphide Street Broken Hill NSW 2880 Ph 08 8082 5200 21 Mitchell Street Bourke NSW 2840 Ph 02 6872 2144 62 Marshall Street Cobar NSW 2835 Ph 02 6836 1575 89 Wee Waa Street Walgett NSW 2832 Ph 02 6828 0110 Freecall 1800 032 101 www.western.cma.nsw.gov.au WMA Head Office: Level 2, 160 Clarence Street Sydney NSW 2000 Ph 02 9299 2855 Fax 02 9262 6208 E [email protected] W www.wmawater.com.au warrego river scoping study - page 2 1. Warrego River Scoping Study – Summary 1.1. Project Rationale and Objectives The Queensland portion of the Warrego is managed under the Warrego, Paroo, Bulloo and Nebine Water Resource Plan (WRP) (2003) and the Resource Operation Plan (ROP) (2006). At present, there is no planning instrument in NSW. As such, there was concern in the community that available information be consolidated and assessed for usability for the purposes of supporting development of a plan in NSW and for future reviews of the QLD plan. There was also concern that an assessment be undertaken of current hydrologic impacts due to water resource development and potential future impacts. As a result, the Western Catchment Management Authority (WCMA) commissioned WMAwater to undertake a scoping study for the Warrego River and its tributaries and effluents. This study was to synthesise and identify gaps in knowledge / data relating to hydrology, flow dependent environmental assets and water planning instruments. -

Queensland Water Quality Guidelines 2009

Queensland Water Quality Guidelines 2009 Prepared by: Environmental Policy and Planning, Department of Environment and Heritage Protection © State of Queensland, 2013. Re-published in July 2013 to reflect machinery-of-government changes, (departmental names, web addresses, accessing datasets), and updated reference sources. No changes have been made to water quality guidelines. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5470. This publication can be made available in an alternative format (e.g. -

FLOOD WARNING SYSTEM for the COOPER CREEK CATCHMENT

Bureau Home > Australia > Queensland > Rainfall & River Conditions > River Brochures > Thomson, Barcoo and Cooper FLOOD WARNING SYSTEM for the COOPER CREEK CATCHMENT This brochure describes the flood warning system operated by the Australian Government, Bureau of Meteorology for the Thomson, Barcoo Rivers and Cooper Creek. It includes reference information which will be useful for understanding Flood Warnings and River Height Bulletins issued by the Bureau's Flood Warning Centre during periods of high rainfall and flooding. Contained in this document is information about: (Last updated September 2019) Flood Risk Previous Flooding Flood Forecasting Local Information Flood Warnings and Bulletins Interpreting Flood Warnings and River Height Bulletins Flood Classifications Other Links Cooper Creek at Nappa Merrie Flood Risk The Thomson-Barcoo-Cooper catchment drains an area of approximately 237,000 square kilometres and is the largest river basin in Queensland. The catchment falls within the Lake Eyre basin, the largest and only co- ordinated internal drainage system in Australia with no external outlet, and which covers over 1.1 million square kilometres of central Australia. Floodwaters reach Lake Eyre after major flood events in the Cooper. The two main tributaries, the Thomson and Barcoo Rivers, merge into the Cooper Creek approximately 40 kilometres upstream of Windorah. The Thomson River and its tributaries flow in a general southerly direction and has several of the larger towns of the region including Longreach and Muttaburra along its banks. The Barcoo River flows in a general westerly direction and has major centres such as Isisford, Blackall, Barcaldine, Jericho and Tambo in its catchment. The Thomson-Barcoo-Cooper basin can be divided into two distinct areas: * Above Windorah, numerous well-defined creeks and channels flow into the Thomson and Barcoo. -

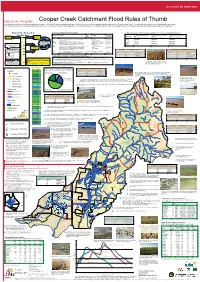

Cooper Creek Catchment Flood Rules of Thumb This Guide Has Used the Best Information Available at Present

QueenslandQueenslandthethe Smart Smart State State How to use this guide: Cooper Creek Catchment Flood Rules of Thumb This guide has used the best information available at present. It is intended to help you assess what type of flood is likely to occur in your area and indicate what amount of feed you might expect. You may wish to record your own flooding guides on the map. You can add more value to this guide by participating in an MLA EDGEnetwork Grazing Land Management (GLM) training package. GLM training helps you identify land types and flood zones and to develop a grazing management plan for your property Amount of rain needed Channel Country Flood descriptions Estimated Summer Flood Pasture Growth in the Channel Country Floodplains. Frequently flooded plains Occasionally flooded plains Swamps and depressions for flooding Flood type Description Land Hydrology Pasture growth Isolated Systems which supports: Flood type (C1) (C2) (C3) Widespread Widespread Rain 100 mm Localised Rain “HANDY” to flooded “GOOD” flood Then increases (kg DM/ha of useful feed) (kg DM/ha of useful feed) (kg DM/ha of useful feed) 95 “GOOD” flood Good Good floods are similar to handy floods, but cover a much higher C1, C3, C2 Flooded across most of 85 - 100% of to proportion of the floodplain (75% or more) and grow more feed per floodplains potential cattle Good 1200-2500 1500-3500 4500-8000 90 area than a handy flood. 80-100% inundation numbers 85 IF in 24-72 hrs Handy Handy floods occur when the water escapes from the gutters, C1, C3 Pushing out of gutters across 45 - 85% of Handy 750-1500 100-250 3500-6500 80 PRIOR, rains of (or useful) connecting up to form the large sheets of water. -

South West Queensland Floods March 2010

South West Queensland Floods March 2010 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1. Floodwaters inundate the township of Bollon. Photo supplied by Bill Speedy. 2. Floodwaters at the Autumnvale gauging station on the lower Bulloo River. Photo supplied by R.D. & C.B. Hughes. 3. Floodwaters from Bradley’s Gully travel through Charleville. 4. Floodwaters from Bungil Creek inundate Roma. Photo supplied by the Maranoa Regional Council. 5. Floodwaters at the confluence of the Paroo River and Beechal Creek. Photo supplied by Cherry and John Gardiner. 6. Balonne River floodwaters inundate low lying areas of St. George. Photo supplied by Sally Nichol. 7. Floodwaters from the Moonie River inundate Nindigully. Photo supplied by Sally Nichol. 8. Floodwaters from the Moonie River inundate the township of Thallon. Photo supplied by Sally Nichol. Revision history Date Version Description 6 June 2010 1.0 Original Original version of this report contained an incorrect date for the main flood peak at Roma. Corrected to 23 June 2010 1.1 8.1 metres on Tuesday 2 March 2010. See Table 3.1.1. An approximate peak height has been replaced for Bradley’s Gully at Charleville. New peak height is 4.2 28 June 2010 1.2 metres on Tuesday 2 March 2010 at 13:00. See Table 3.1.1. Peak height provided from flood mark at Teelba on 01 July 2010 1.3 Teelba Creek. See Table 3.1.1. 08 Spectember Peak height provided from flood mark at Garrabarra 1.4 2010 on Bungil Creek. See Table 3.1.1.