Tlabs: a Teaching and Learning Community of Practice – What Is It, Does It Work and Tips for Doing One of Your Own

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edith Cowan University Office of the Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Strategic Partnerships)

Edith Cowan University Office of the Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Strategic Partnerships) Achieving Gender Equality at Edith Cowan University (ECU) – Discussion Paper The Science Academic Gender Equity (SAGE) Pilot of the Athena SWAN Charter in Australia What is Athena SWAN? Athena SWAN is now an international accreditation scheme which recognises a commitment to supporting and advancing women's careers in science, technology, engineering, maths and medicine (STEMM) in higher education and research.1 The term ‘Athena’ refers to a UK based ‘Athena Project’ that began in 1999 with the aim of addressing the loss of women in science, engineering and technology based disciplines as they progressed through academia. By establishing extensive associations throughout the UK higher education sector, the project developed good practice guidelines which improved female academic retention. The project closed in 2007 however its mission continues through initiatives including the Athena SWAN Charter. The acronym ‘SWAN’ stands for the Scientific Women’s Academic Network, an entity that collects real life views and experiences of women in academia across the UK. The Athena SWAN Charter combines these two elements in advancing the representation of women in science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine (STEMM). Having commenced in the UK, the initiative has an extensive history there of advancing the careers of women in higher education and research sectors since it was established in 2005, and the scheme has been highly successful in improving the promotion and retention of women within STEMM. With such success, the Pilot has now been launched in Australia by the Science Academic Gender Equity (SAGE) initiative which addresses gender equality in the STEMM sector. -

Download This PDF File

Abstracts INTRODUCING AUTHENTIC RESEARCH EXPERIENCE AT THE UNDERGRADUATE LEVEL Jemma Berrya, Aaron Beasleyb, Zoe Bainesc, Alex Kungc, Hayley Taskerc, Madison Trinderc, Elin Grayd Presenting Author: Jemma Berry ([email protected]) aLecturer, School of Medical and Health Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Perth Western Australia 6027, Australia bMSc Candidate, School of Medical and Health Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Perth Western Australia 6027, Australia cUndergraduate Student, School of Medical and Health Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Perth Western Australia 6027, Australia dPostdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Medical and Health Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Perth Western Australia 6027, Australia KEYWORDS: skills transfer, experience, research One of the challenges facing new graduates is that they don’t necessarily know what lies out there for them once they have finished their degrees. Not all students are aware of the jobs they are qualified for, or the post-graduate opportunities that may be available to them. In an attempt to engage with undergraduate students and give them a glimpse into life after graduation, we ran a pilot Cancer Research Summer Project (CRSP). In this pilot program we took four high-achieving second-year biomedical science students through a three-week research project, which exposed them to a real-life laboratory experience, and also provided them with additional skills training in areas such as scientific journal article writing and database mining. Students were given a fully immersive laboratory experience, receiving the type of instruction and supervision they could expect in either post-graduate study or out in the workforce, with some autonomy, and successes and failures driven by their own hands. -

Teaching English As a Foreign Language to Grade 6 Students in Thailand: Cooperative Learning Versus Thai Communicative Method

Edith Cowan University Research Online EDU-COM International Conference Conferences, Symposia and Campus Events 1-1-2006 Teaching English as a Foreign Language to Grade 6 Students in Thailand: Cooperative Learning versus Thai Communicative Method Sutaporn Chayaratheee Muban Chombueng Rajabhat University Russell F. Waugh Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ceducom Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons EDU-COM 2006 International Conference. Engagement and Empowerment: New Opportunities for Growth in Higher Education, Edith Cowan University, Perth Western Australia, 22-24 November 2006. This Conference Proceeding is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ceducom/69 Chayaratheee, S. and Waugh, R. Muban Chombueng Rajabhat University, Thailand and Edith Cowan University, Australia. Teaching English as a Foreign Language to Grade 6 Students in Thailand: Cooperative Learning versus Thai Communicative Method Sutaporn Chayaratheee Department of Education Muban Chombueng Rajabhat University, Thailand [email protected] and Russell F. Waugh School of Education Edith Cowan University, Australia [email protected] Key words: English as a foreign (second) language, Grade 6 students, Thailand, Rasch measurement, English comprehension, attitude and behaviour, cooperative learning, Thai Communicative English teaching method, ANOVA ABSTRACT This study compared a cooperative learning method of teaching English to Prathom (grade) 6 secondary students in Thailand and a communicative method. Rasch-generated linear scales were created to measure reading comprehension (based on 28 items with 300 students) and attitude and behaviour to learning EFL (based on 24 items with 300 students). The data for both scales had a good fit to a Rasch measurement model, good separation of measures compared to the errors, good targeting, and the response categories were answered consistently and logically, so that valid inferences could be drawn. -

Edith Cowan College Your Pathway to ECU ECC Your Pathway to EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY 2017/18

2017/18 Perth, Australia Study at Edith Cowan College Your Pathway to ECU ECC Your pathway to EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY 2017/18 Your future starts here • Edith Cowan College (ECC) provides pathway programs to Edith Cowan University (ECU), delivering a range of programs designed to provide a high quality education so that you are university-ready. • ECC students receive individual attention from their lecturers in smaller classes than the university, with access to high quality English language programs and additional free study support programs. ECC is located on ECU’s campus, providing students with access to the university’s state-of-the-art facilities including biology labs, computer labs, engineering ECU has been labs, lecture rooms and library. • ECC has embedded employability and English ranked the language skills within its programs so that you can reach your potential and ‘get that job’. This ensures that graduates are well prepared and attractive to top public university employers by standing out from other students. • ECC is focused on maximising your student experience with a range of social programs to help in Australia for you make lifelong friends and enjoy studying at ECC. Activities include barbecues, sporting activities (e.g. basketball, cricket, netball, soccer and volleyball) and student satisfaction help from your Student Leader. in the QILT (Quality Indicators • Read on to find out more about studying at ECC. for Learning and Teaching) in 2017. 1 Your pathway to a degree from Edith Cowan University Edith Cowan College (ECC) provides alternative pathways to Edith Cowan University (ECU) for students who may not qualify for direct entry into a degree program and are looking for a supportive learning environment. -

Unai Members List August 2021

UNAI MEMBER LIST Updated 27 August 2021 COUNTRY NAME OF SCHOOL REGION Afghanistan Kateb University Asia and the Pacific Afghanistan Spinghar University Asia and the Pacific Albania Academy of Arts Europe and CIS Albania Epoka University Europe and CIS Albania Polytechnic University of Tirana Europe and CIS Algeria Centre Universitaire d'El Tarf Arab States Algeria Université 8 Mai 1945 Guelma Arab States Algeria Université Ferhat Abbas Arab States Algeria University of Mohamed Boudiaf M’Sila Arab States Antigua and Barbuda American University of Antigua College of Medicine Americas Argentina Facultad de Ciencias Económicas de la Universidad de Buenos Aires Americas Argentina Facultad Regional Buenos Aires Americas Argentina Universidad Abierta Interamericana Americas Argentina Universidad Argentina de la Empresa Americas Argentina Universidad Católica de Salta Americas Argentina Universidad de Congreso Americas Argentina Universidad de La Punta Americas Argentina Universidad del CEMA Americas Argentina Universidad del Salvador Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Avellaneda Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Cordoba Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Jujuy Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de la Pampa Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Quilmes Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Rosario Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de -

UNIVERSITY ECTS EQUIVALENT Per Year Per Semestrer Per Credit Course

UNIVERSITY CREDIT LOAD ECTS EQUIVALENT STUDY LOAD AND CREDITS VALUE Per credit course (typically 4 Per Year Per Semestrer courses/modules per semester) Full-time per Semester You are required to complete a full- time study load that equals 45-60 La 120 credit points (90 CP) at La Trobe 60 credit points (45 CP) at La Trobe 15 credit points at La Trobe Trobe credit points per semester, or = = = 90-120 credit points for two La Trobe University 60 ECTS at Udine 30 ECTS at Udine 7,5 ECTS at Udine semesters (a full academic year). A standard course at Griffith is considered to equate to 80 credit points at Griffith 40 credit points at Griffith 10 credit points at Griffith approximately 10 hours per week, = = = including all forms of teaching Griffith University 60 ECTS at Udine 30 ECTS at Udine 7,5 ECTS at Udine contact and private study. International onshore students must complete their studies within the Confirmation of Enrolment (CoE) date. Time extensions require a new CoE and are only permitted in compassionate or compelling circumstances or for students who have complied with an intervention strategy. International onshore 96 credit points at Southern Cross 48 credit points at Southern Cross 12 credit points at Southern Cross students must enrol in a full time = = = load (8 units per year) as indicated 24 Units, 288 credits point per 3 Southern Cross University 60 ECTS at Udine 30 ECTS at Udine 7,5 ECTS at Udine in their study plan. Years Bachelor 9 credit points (most students complete 12 CP) at JCU 3 credit points at JCU = = A typical credit load value per James Cook University 30 ECTS at Udine 7,5 ECTS at Udine subject is 3 credit points. -

College Codes (Outside the United States)

COLLEGE CODES (OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES) ACT CODE COLLEGE NAME COUNTRY 7143 ARGENTINA UNIV OF MANAGEMENT ARGENTINA 7139 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF ENTRE RIOS ARGENTINA 6694 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF TUCUMAN ARGENTINA 7205 TECHNICAL INST OF BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA 6673 UNIVERSIDAD DE BELGRANO ARGENTINA 6000 BALLARAT COLLEGE OF ADVANCED EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 7271 BOND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7122 CENTRAL QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7334 CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6610 CURTIN UNIVERSITY EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6600 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 7038 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6863 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7090 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6901 LA TROBE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6001 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6497 MELBOURNE COLLEGE OF ADV EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 6832 MONASH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7281 PERTH INST OF BUSINESS & TECH AUSTRALIA 6002 QUEENSLAND INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 6341 ROYAL MELBOURNE INST TECH EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6537 ROYAL MELBOURNE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 6671 SWINBURNE INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 7296 THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA 7317 UNIV OF MELBOURNE EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7287 UNIV OF NEW SO WALES EXCHG PROG AUSTRALIA 6737 UNIV OF QUEENSLAND EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 6756 UNIV OF SYDNEY EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7289 UNIV OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA EXCHG PRO AUSTRALIA 7332 UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE AUSTRALIA 7142 UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA AUSTRALIA 7027 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIA 7276 UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE AUSTRALIA 6331 UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND AUSTRALIA 7265 UNIVERSITY -

Career-Related Programme at a Glance

The Career-related Programme at a glance The International Baccalaureate (IB) Career-related Programme (CP) is an innovative international education pathway that offers a rewarding blend of academic subjects and career-related studies. Tailored to students who want to focus on career-related learning in the last two years of secondary school, the CP develops applicable, transferable, lifelong skills that prepares them for higher education, apprenticeships or employment. The CP around the globe: 139 CP schools in 23+ countries* 1,500+ graduates in 2016** 1,900+ CP students expected to sit in May CP schools worldwide Most popular Diploma Programme examinations in 2017 courses among CP students (2015) Since its launch in 2012, student registration has grown from 14% 27% 2.0 to 2.7 14% 30% exams*** 73% CP students represent a variety of nations: 20% 22% Australia Finland Germany Mexico Peru Portugal Private schools English A Singapore Spain Mathematical studies Thailand United Arab Emirates State schools United Kingdom United States Business management History *as of November 2016 **May exam session only Psychology *** indicates that CP students are taking more DP courses than the requirement ©International Baccalaureate Organization 2016 International Baccalaureate® | Baccalauréat International® | Bachillerato Internacional® A flexible educational framework With the CP, schools are able to create their own distinctive version of the programme and select career pathways that suit their students and local community needs. Career-related studies The CP offers schools the flexibility to select the career pathways they want to offer, such as: business engineering health and bioscience art and design sports management and more ... Academic rigour All CP students are required to take at least two Diploma Programme (DP) courses. -

Tlabs: a Teaching and Learning Community of Practice – What Is It, Does It Work and Tips for Doing One of Your Own

Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice Volume 17 Issue 5 17.5 Article 9 2020 TLABs: A Teaching and Learning Community of Practice – What is it, Does It Work and Tips for Doing One of Your Own Shelley Beatty Edith Cowan University, [email protected] Kim Clark Edith Cowan University, [email protected] Jo Lines Edith Cowan University, [email protected] Sally-Anne Doherty Edith Cowan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp Recommended Citation Beatty, S., Clark, K., Lines, J., & Doherty, S. (2020). TLABs: A Teaching and Learning Community of Practice – What is it, Does It Work and Tips for Doing One of Your Own. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 17(5). https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol17/iss5/9 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] TLABs: A Teaching and Learning Community of Practice – What is it, Does It Work and Tips for Doing One of Your Own Abstract Communities of Practice are an increasingly common tool used to support novice academics in higher education settings. Initiated in 2015 at a Western Australian University, TLABs is an acronym for ‘Teaching and Learning for Level A and B’ academic staff and was designed to build a community of practice to mentor junior academics; help them develop their teaching skills; and enhance academic careers. The paper describes the nature of TLABs; how it is experienced from the perspective of participants and provides recommendations for implementing a successful teaching and learning community of practice in a higher education setting. -

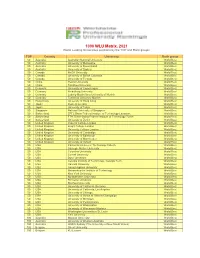

WLU Table 2021

1000 WLU Matrix. 2021 World Leading Universities positions by the TOP and Rank groups TOP Country University Rank group 50 Australia Australian National University World Best 50 Australia University of Melbourne World Best 50 Australia University of Queensland World Best 50 Australia University of Sydney World Best 50 Canada McGill University World Best 50 Canada University of British Columbia World Best 50 Canada University of Toronto World Best 50 China Peking University World Best 50 China Tsinghua University World Best 50 Denmark University of Copenhagen World Best 50 Germany Heidelberg University World Best 50 Germany Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich World Best 50 Germany Technical University Munich World Best 50 Hong Kong University of Hong Kong World Best 50 Japan Kyoto University World Best 50 Japan University of Tokyo World Best 50 Singapore National University of Singapore World Best 50 Switzerland EPFL Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne World Best 50 Switzerland ETH Zürich-Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich World Best 50 Switzerland University of Zurich World Best 50 United Kingdom Imperial College London World Best 50 United Kingdom King's College London World Best 50 United Kingdom University College London World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Cambridge World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Edinburgh World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Manchester World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Oxford World Best 50 USA California Institute of Technology Caltech World Best 50 USA Carnegie -

About Australia…

NKU Academic Exchange in Perth, Australia https://www.cia.gov Spend a semester or an academic year studying at Edith Cowan University! A brief introduction… Office of Education Abroad (859) 572-6908 NKU Academic Exchanges The Office of Education Abroad offers academic exchanges as a study abroad option for independent and mature NKU students interested in a semester or year-long immersion experience in another country. The information in this packet is meant to provide an overview of the experience available through an academic exchange in Perth, Australia. However, please keep in mind that this information, especially that regarding visa requirements, is subject to change. It is the responsibility of each NKU student participating in an exchange to take the initiative in the pre-departure process with regards to visa application, application to the exchange university, air travel arrangements, housing arrangements, and pre-approval of courses. Before and after departure for an academic exchange, the Office of Education Abroad will remain a resource and guide for participating exchange students. Australia Australia, made up of eight distinct states, is the sixth largest country in the world. Each state has its own unique qualities that attract tourists, from the sunny beaches of the Gold Coast to the rugged outback in the west. Australia is famous for its extensive eco-diversity and wide range of habitats, including the Great Barrier Reef, the world’s largest coral reef, just a short distance off the northeast coast. Comprised of the mainland and also numerous islands surrounding it, including Tasmania, the Commonwealth of Australia has a long and rich history. -

Edith Cowan University Faculty of Health, Engineering and Science

Edith Cowan University Faculty of Health, Engineering and Science Faculty of Health, Engineering and Science Research Unit Annual Report RESEARCH UNIT NAME: Centre for Ecosystem Management RESEARCH UNIT LEVEL (tick): Level I Research Group* Level II Research Centre Level III Research Institute Centre of Excellence Research Group may not be able to address questions with an asterisk below REPORTING YEAR: 2013 BRIEF OVERVIEW AND HIGHLIGHTS (Outline major activities conducted in past year) In 2013, CEM member research activities have resulted in an increase in research income with 17 new projects totalling more than $2.7 million, including 3 Category 1 projects (totalling >$1.5 million). Research outputs have been maintained with 45 publications, including 5 books/book chapters, 25 peer-reviewed papers, 5 conferences papers and 10 reports. Events/Achievements A major highlight for 2013 was the substantial engagement activities undertaken by members to promote CEM and ECU research outcomes and expertise. A total of 33 engagement activities with state, national international entities were undertaken. Other highlights included a half- day research symposium. This was held during the ECU Research Week and was well attended. The symposium topic, Ecosystem Management in a Drying Landscape, was of particular interest to over 90 research collaborators from outside the university. The outcome of the research day has already led to new collaborative projects and we hope that such partnerships continue to grow into the future. MEMBERSHIP (Full Title