The Language of Lace and Embroidery from the Court

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Allure of Chanel (Illustrated) Online

YGArF (Free pdf) The Allure of Chanel (Illustrated) Online [YGArF.ebook] The Allure of Chanel (Illustrated) Pdf Free Paul Morand *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1733764 in Books 2013-11-12 2013-11-12Original language:FrenchPDF # 1 9.45 x .96 x 6.75l, 1.50 #File Name: 1908968923224 pages | File size: 52.Mb Paul Morand : The Allure of Chanel (Illustrated) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Allure of Chanel (Illustrated): 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. but between the lines is a great deal of wisdom and self- acknowledgement of both her own ...By BelleriveFascinating look at Chanel's spin on her own life. While she is brutally candid about some aspects, others are completely fabricated to throw a more positive and morally acceptable light on them. You won't get the whole truth, but between the lines is a great deal of wisdom and self- acknowledgement of both her own talent and shortcomings. A must for any die-hard Chanel fan who has read other notable biographies on this endless intriguing fashion icon.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. like hisBy Costomerwell written,i started collect his works,like his style1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Always Fascinating- Coco ChanelBy MicheleAn almost stream of consciousness from the iconic designer about who she was, who she saw, what she did and why. How much is truth, fiction or design in this reconstructed narrative? Fascinating. -

Palmetto Tatters Guild Glossary of Tatting Terms (Not All Inclusive!)

Palmetto Tatters Guild Glossary of Tatting Terms (not all inclusive!) Tat Days Written * or or To denote repeating lines of a pattern. Example: Rep directions or # or § from * 7 times & ( ) Eg. R: 5 + 5 – 5 – 5 (last P of prev R). Modern B Bead (Also see other bead notation below) notation BTS Bare Thread Space B or +B Put bead on picot before joining BBB B or BBB|B Three beads on knotting thread, and one bead on core thread Ch Chain ^ Construction picot or very small picot CTM Continuous Thread Method D Dimple: i.e. 1st Half Double Stitch X4, 2nd Half Double Stitch X4 dds or { } daisy double stitch DNRW DO NOT Reverse Work DS Double Stitch DP Down Picot: 2 of 1st HS, P, 2 of 2nd HS DPB Down Picot with a Bead: 2 of 1st HS, B, 2 of 2nd HS HMSR Half Moon Split Ring: Fold the second half of the Split Ring inward before closing so that the second side and first side arch in the same direction HR Half Ring: A ring which is only partially closed, so it looks like half of a ring 1st HS First Half of Double Stitch 2nd HS Second Half of Double Stitch JK Josephine Knot (Ring made of only the 1st Half of Double Stitch OR only the 2nd Half of Double Stitch) LJ or Sh+ or SLJ Lock Join or Shuttle join or Shuttle Lock Join LPPCh Last Picot of Previous Chain LPPR Last Picot of Previous Ring LS Lock Stitch: First Half of DS is NOT flipped, Second Half is flipped, as usual LCh Make a series of Lock Stitches to form a Lock Chain MP or FP Mock Picot or False Picot MR Maltese Ring Pearl Ch Chain made with pearl tatting technique (picots on both sides of the chain, made using three threads) P or - Picot Page 1 of 4 PLJ or ‘PULLED LOOP’ join or ‘PULLED LOCK’ join since it is actually a lock join made after placing thread under a finished ring and pulling this thread through a picot. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Land of Horses 2020

LAND OF HORSES 2020 « Far back, far back in our dark soul the horse prances… The horse, the horse! The symbol of surging potency and power of movement, of action in man! D.H. Lawrence EDITORIAL With its rich equine heritage, Normandy is the very definition of an area of equine excellence. From the Norman cavalry that enabled William the Conqueror to accede to the throne of England to the current champions who are winning equestrian sports events and races throughout the world, this historical and living heritage is closely connected to the distinctive features of Normandy, to its history, its culture and to its specific way of life. Whether you are attending emblematic events, visiting historical sites or heading through the gates of a stud farm, discovering the world of Horses in « Normandy is an opportunity to explore an authentic, dynamic and passionate region! Laurence MEUNIER Normandy Horse Council President SOMMAIRE > HORSE IN NORMANDY P. 5-13 • normandy the world’s stables • légendary horses • horse vocabulary INSPIRATIONS P. 14-21 • the fantastic five • athletes in action • les chevaux font le show IIDEAS FOR STAYS P. 22-29 • 24h in deauville • in the heart of the stud farm • from the meadow to the tracks, 100% racing • hooves and manes in le perche • seashells and equines DESTINATIONS P. 30-55 • deauville • cabourg and pays d’auge • le pin stud farm • le perche • saint-lô and cotentin • mont-saint-michel’s bay • rouen SADDLE UP ! < P. 56-60 CABOURG AND LE PIN PAYS D’AUGE STUD P. 36-39 FARM DEAUVILLE P. -

NEEDLE LACES Battenberg, Point & Reticella Including Princess Lace 3Rd Edition

NEEDLE LACES BATTENBERG, POINT & RETICELLA INCLUDING PRINCESS LACE 3RD EDITION EDITED BY JULES & KAETHE KLIOT LACIS PUBLICATIONS BERKELEY, CA 94703 PREFACE The great and increasing interest felt throughout the country in the subject of LACE MAKING has led to the preparation of the present work. The Editor has drawn freely from all sources of information, and has availed himself of the suggestions of the best lace-makers. The object of this little volume is to afford plain, practical directions by means of which any lady may become possessed of beautiful specimens of Modern Lace Work by a very slight expenditure of time and patience. The moderate cost of materials and the beauty and value of the articles produced are destined to confer on lace making a lasting popularity. from “MANUAL FOR LACE MAKING” 1878 NEEDLE LACES BATTENBERG, POINT & RETICELLA INLUDING PRINCESS LACE True Battenberg lace can be distinguished from the later laces CONTENTS by the buttonholed bars, also called Raleigh bars. The other contemporary forms of tape lace use the Sorrento or twisted thread bar as the connecting element. Renaissance Lace is INTRODUCTION 3 the most common name used to refer to tape lace using these BATTENBERG AND POINT LACE 6 simpler stitches. Stitches 7 Designs 38 The earliest product of machine made lace was tulle or the PRINCESS LACE 44 RETICELLA LACE 46 net which was incorporated in both the appliqued hand BATTENBERG LACE PATTERNS 54 made laces and later the elaborate Leavers laces. It would not be long before the narrow tapes, in fancier versions, would be combined with this tulle to create a popular form INTRODUCTION of tape lace, Princess Lace, which became and remains the present incarnation of Belgian Lace, combining machine This book is a republication of portions of several manuals made tapes and motifs, hand applied to machine made tulle printed between 1878 and 1938 dealing with varieties of and embellished with net embroidery. -

Replica Styles from 1795–1929

Replica Styles from 1795–1929 AVENDERS L REEN GHistoric Clothing $2.00 AVENDERS L REEN GHistoric Clothing Replica Styles from 1795–1929 Published by Lavender’s Green © 2010 Lavender’s Green January 2010 About Our Historic Clothing To our customers ... Lavender’s Green makes clothing for people who reenact the past. You will meet the public with confidence, knowing that you present an ac- curate picture of your historic era. If you volunteer at historic sites or participate in festivals, home tours, or other historic-based activities, you’ll find that the right clothing—comfortable, well made, and accu- rate in details—will add so much to the event. Use this catalog as a guide in planning your period clothing. For most time periods, we show a work dress, or “house dress.” These would have been worn for everyday by servants, shop girls, and farm wives across America. We also show at least one Sunday gown or “best” dress, which a middle-class woman would save for church, weddings, parties, photos, and special events. Throughout the catalog you will see drawings of hats and bonnets. Each one is individually designed and hand-made; please ask for a bid on a hat to wear with your new clothing. Although we do not show children’s clothing on most of these pages, we can design and make authentic clothing for your young people for any of these time periods. Generally, these prices will be 40% less than the similar adult styles. The prices given are for a semi-custom garment with a dressmaker- quality finish. -

The Bread-Winners

READWINN'^t' -\ ^^?^!lr^^ <^.li i^w LaXi Digitized by the Internet Arcinive in 2011 with funding from The Institute of Museum and Library Services through an Indiana State Library LSTA Grant http://www.archive.org/details/breadwinnerssociOOhayj THE BREAD-WINNERS 21 Social Sttttra NEW YORK HARPER & BROTHERS, FRANKLIN SQUARE Ck)p7right, 1883, by The Century Company. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, by HARPER & BROTHERS, In the Oflace of the Librarian of Congress, at "Washingtoa All righit teterved. THE BREAD-WINNEUS. A MORNING CALL. A French clock on the mantel-piece, framed of brass and crystal, wliicli betrayed its inner structure as tlie transparent sides of some insects betray tlieir vital processes, struck ten with the mellow and lingering clangor of a distant cathedral bell. A gentleman, who was seated in front of the lire read- ing a newspaper, looked up at the clock to see what hour it was, to save himself the trouble of counting the slow, musical strokes. The eyes he raised were light gray, with a blue glint of steel in them, shaded by lashes as black as jet. The hair was also as black as hair can be, and was parted near the middle of his forehead. It was inclined to curl, but had not the length required by this inclination. The dark brown mustache was the only ornament the razor had spared on the wholesome face, the outline of which was clear and keen. The face suited the hands—it had the refinement and gentle- ness of one delicately bred, and the vigorous lines and color of one equally at home in field and court; 6 THE BREAD-WINNERS. -

Bobbin Lace You Need a Pattern Known As a Pricking

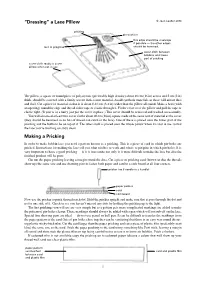

“Dressing” a Lace Pillow © Jean Leader 2014 pricking pin-cushion this edge should be a selvage if possible — the other edges lace in progress should be hemmed. cover cloth between bobbins and lower part of pricking cover cloth ready to cover pillow when not in use The pillow, a square or round piece of polystyrene (preferably high density) about 40 cm (16 in) across and 5 cm (2 in) thick, should be covered with a firmly woven dark cotton material. Avoid synthetic materials as these will attract dust and fluff. Cut a piece of material so that it is about 8-10 cm (3-4 in) wider than the pillow all round. Make a hem (with an opening) round the edge and thread either tape or elastic through it. Fit the cover over the pillow and pull the tape or elastic tight. (If you’re in a hurry just pin the cover in place.) This cover should be removed and washed occasionally. You will also need at least two cover cloths about 40 cm (16 in) square made of the same sort of material as the cover (they should be hemmed so no bits of thread can catch in the lace). One of these is placed over the lower part of the pricking and the bobbins lie on top of it. The other cloth is placed over the whole pillow when it is not in use so that the lace you’re working on stays clean. Making a Pricking In order to make bobbin lace you need a pattern known as a pricking. -

Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of Terms Used in the Documentation – Blue Files and Collection Notebooks

Book Appendix Glossary 12-02 Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of terms used in the documentation – Blue files and collection notebooks. Rosemary Shepherd: 1983 to 2003 The following references were used in the documentation. For needle laces: Therese de Dillmont, The Complete Encyclopaedia of Needlework, Running Press reprint, Philadelphia, 1971 For bobbin laces: Bridget M Cook and Geraldine Stott, The Book of Bobbin Lace Stitches, A H & A W Reed, Sydney, 1980 The principal historical reference: Santina Levey, Lace a History, Victoria and Albert Museum and W H Maney, Leeds, 1983 In compiling the glossary reference was also made to Alexandra Stillwell’s Illustrated dictionary of lacemaking, Cassell, London 1996 General lace and lacemaking terms A border, flounce or edging is a length of lace with one shaped edge (headside) and one straight edge (footside). The headside shaping may be as insignificant as a straight or undulating line of picots, or as pronounced as deep ‘van Dyke’ scallops. ‘Border’ is used for laces to 100mm and ‘flounce’ for laces wider than 100 mm and these are the terms used in the documentation of the Powerhouse collection. The term ‘lace edging’ is often used elsewhere instead of border, for very narrow laces. An insertion is usually a length of lace with two straight edges (footsides) which are stitched directly onto the mounting fabric, the fabric then being cut away behind the lace. Ocasionally lace insertions are shaped (for example, square or triangular motifs for use on household linen) in which case they are entirely enclosed by a footside. See also ‘panel’ and ‘engrelure’ A lace panel is usually has finished edges, enclosing a specially designed motif. -

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identification

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace DATS in partnership with the V&A DATS DRESS AND TEXTILE SPECIALISTS 1 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Text copyright © Jeremy Farrell, 2007 Image copyrights as specified in each section. This information pack has been produced to accompany a one-day workshop of the same name held at The Museum of Costume and Textiles, Nottingham on 21st February 2008. The workshop is one of three produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A, funded by the Renaissance Subject Specialist Network Implementation Grant Programme, administered by the MLA. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audiences. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the public. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750 -1950 Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740-1890 Front cover image: Detail of a triangular shawl of white cotton Pusher lace made by William Vickers of Nottingham, 1870. The Pusher machine cannot put in the outline which has to be put in by hand or by embroidering machine. The outline here was put in by hand by a woman in Youlgreave, Derbyshire. (NCM 1912-13 © Nottingham City Museums) 2 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Contents Page 1. List of illustrations 1 2. Introduction 3 3. The main types of hand and machine lace 5 4. -

Press Release: Fresh, Clean & Profoundly Sensual BLEU De

825 Seventh Avenue New York, NY 10019 Tel: 212-474-0000 Fax: 212-474-0003 Website: www.mecglobal.com Press Release: Fresh, Clean & Profoundly Sensual BLEU de CHANEL Contact: Kisha S. Facey (0730) June 4, 2010 Picture it... Paris, France in the 1930’s. The beautiful Eiffel Tower in the background and the Louvre filled with exquisite art paintings. The famed soprano opera singer Jane Bathori can be heard throughout the cafes. The French natives are buzzing about the new women’s fragrance developed by Borjois Paris, “Soirée à Paris” (Evening in Paris). An unforgettable provocative fragrance with a rich floral bouquet and a hint of wood scents. This eau de perfume deemed to be worn by a maximum number of women all over the world. Picture it… Paris, France in 2010 Chanel has re-launched the Soirée à Paris but with a twist, its for men! “Bleu de Chanel” will debut in France on August 19, 2010. It will be distributed in the U.S. on September 10, 2010. The eau de toilette spray will be offered in a 50 and 100ml bottles. The striking square cobalt blue bottle is a timeless classic yet a rare modern day romantic fragrance. Developer Jacques Polge, wanted to keep the original scent of the Soirée à Paris adding masculinity aroma. The blended Bleu de Chanel scents are various woods with added hints of nutmeg, peppermint, citrus, ginger and jasmine. This will allure just about any woman who knows a good fragrance when she smells it. The :30 commercials will begin airing in France during mid-July. -

Les Métiers D'art, D'excellence Et Du Luxe Et Les Savoir-Faire Traditionnels : L'avenir Entre Nos Mains

Les métiers d'art, d'excellence et du luxe et les savoir-faire traditionnels : L'avenir entre nos mains Rapport à Monsieur le Premier ministre de Madame Catherine DUMAS, Sénatrice de Paris Septembre 2009 Sommaire Introduction ______________________________________________________________ 1 20 propositions pour une nouvelle dynamique en faveur des métiers d’art __________ 3 I. Dans leur diversité, les métiers d’art constituent un atout certain pour la France ______________________________________________________________ 5 A. Une hétérogénéité à maîtriser pour plus de visibilité________________________ 5 1. Les définitions existantes, un point de départ très utile ______________________ 5 a) Les trois critères des métiers d’art_____________________________________ 5 b) La nomenclature officielle___________________________________________ 5 2. Une diversité qui rend leur délimitation complexe __________________________ 5 a) Description n’est pas définition_______________________________________ 5 b) Les trois grandes familles d’activités __________________________________ 6 (1) Les métiers de tradition_________________________________________ 6 (2) Les métiers de restauration ______________________________________ 6 (3) Les métiers de création _________________________________________ 7 3. Une définition plus précise et plus complète pour mieux saisir le réel___________ 8 a) Préciser les critères ________________________________________________ 8 b) Compléter la liste des activités _______________________________________ 9 B. Une place toute