The Late Trecento Fresco Decoration of the Palazzo Datini in Prato

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estratto Le Terre Dei Re

UN FANTASTICO ITINERARIO STORICO E ARCHITETTONICO TRA MEDIOEVO Itineraries E RINASCIMENTO A great historical and architectural tour trough the Middle Ages and Reinassance Le Terre dei Re DAI LONGOBARDI AI VISCONTI The Lands of Kings FROM THE LONGOBARDS TO THE VISCONTI LA PROVINCIA DI PAVIA, THE PROVINCE OF PAVIA, con la forza della qualità e della bellezza, ha selezionato Confident of the beauty of the territory and what it has con gli operatori del territorio 4 itinerari che favoriscono to offer visitors, the provincial authorities have joined with la scoperta di luoghi di grande attrattiva. various organisations operating in the area to draw up four itineraries that will allow travellers to discover intriguing Sono 4 itinerari che suggeriscono approcci diversi new destinations. e che valorizzano le diverse vocazioni di un territorio poco conosciuto e proprio per questo contraddistinto Four different itineraries that present the varied vocations da una freschezza tutta da scoprire. of a little-known territory just waiting to be discovered. Un turismo intelligente fruibile tutti i giorni dell’anno, Intelligent tourism accessible all year-round in the heart vissuto nel cuore del territorio lombardo, fra pianura, of Lombardy - ranging from the plains to the hills and the colline e Appennino, ideale per scoprire la storia, Appenine Mountains, a voyage into the history, the culture la cultura e la natura a pochi passi da casa. and the natural beauty that lies just around the corner. • VIGEVANO • MEDE • PAVIA • MIRADOLO TERME • MORTARA • LOMELLO -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Sassetta's Madonna della Neve. An Image of Patronage Israëls, M. Publication date 2003 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Israëls, M. (2003). Sassetta's Madonna della Neve. An Image of Patronage. Primavera Pers. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 Index Note Page references in bold indicate Avignonese period of the papacy, 108, Bernardino, Saint, 26, 82n, 105 illustrations. 11 in Bertini (family), 3on, 222 - Andrea di Francesco, 19, 21, 30 Abbadia Isola Baccellieri, Baldassare, 15011 - Ascanio, 222 - Abbey of Santi Salvatore e Cirino, Badia Bcrardcnga, 36n - Beatrice di Ascanio, 222, 223 -

The Collaboration of Niccolò Tegliacci and Luca Di Tommè

The Collaboration of Niccolô Tegliacci and Lúea di Tomme This page intentionally left blank J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM Publication No. 5 THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLÔ TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ BY SHERWOOD A. FEHM, JR. !973 Printed by Anderson, Ritchie & Simon Los Angeles, California THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLO TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ The economic and religious revivals which occurred in various parts of Italy during the late Middle Ages brought with them a surge of .church building and decoration. Unlike the typically collective and frequently anonymous productions of the chan- tiers and ateliers north of the Alps which were often passed over by contemporary chroniclers of the period, artistic creativity in Italy during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries documents the emergence of distinct "schools" and personalities. Nowhere is this phenomenon more apparent than in Tuscany where indi- vidual artists achieved sufficient notoriety to appear in the writ- ings of their contemporaries. For example, Dante refers to the fame of the Florentine artist Giotto, and Petrarch speaks warmly of his Sienese painter friend Simone Martini. Information regarding specific artists is, however, often l^ck- ing or fragmentary. Our principal source for this period, The Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects by Giorgio Vasari, was written more than two hundred years after Giotto's death. It provides something of what is now regarded as established fact often interspersed with folk tales and rumor. In spite of the enormous losses over the centuries, a large num- ber of paintings survived from the Dugento and Trecento. Many of these are from Central Italy, and a relatively small number ac- tually bear the signature of the artist who painted them. -

The Mariology of St. Bonaventure As a Source of Inspiration in Italian Late Medieval Iconography

José María SALVADOR GONZÁLEZ, La mariología de San Buenaventura como fuente de inspiración en la iconografía bajomedieval italiana The mariology of St. Bonaventure as a source of inspiration in Italian late medieval iconography La mariología de San Buenaventura como fuente de inspiración en la iconografía bajomedieval italiana1 José María SALVADOR-GONZÁLEZ Universidad Complutense de Madrid [email protected] Recibido: 05/09/2014 Aceptado: 05/10/2014 Abstract: The central hypothesis of this paper raises the possibility that the mariology of St. Bonaventure maybe could have exercised substantial, direct influence on several of the most significant Marian iconographic themes in Italian art of the Late Middle Ages. After a brief biographical sketch to highlight the prominent position of this saint as a master of Scholasticism, as a prestigious writer, the highest authority of the Franciscan Order and accredited Doctor of the Church, the author of this paper presents the thesis developed by St. Bonaventure in each one of his many “Mariological Discourses” before analyzing a set of pictorial images representing various Marian iconographic themes in which we could detect the probable influence of bonaventurian mariology. Key words: Marian iconography; medieval art; mariology; Italian Trecento painting; St. Bonaventure; theology. Resumen: La hipótesis de trabajo del presente artículo plantea la posibilidad de que la doctrina mariológica de San Buenaventura haya ejercido notable influencia directa en varios de los más significativos temas iconográficos -

Renaissance Theories of Vision Edited by John Hendrix, University of Lincoln, UK and Rhode Island School of Design and Roger Williams University, USA, and Charles H

Renaissance Theories of Vision Edited by John Hendrix, University of Lincoln, UK and Rhode Island School of Design and Roger Williams University, USA, and Charles H. Carman, University at Buffalo, USA Visual Culture in Early Modernity December 2010 244 x 172 mm 258 pages Hardback 978-1-4094-0024-0 £65.00 Includes 18 b&w illustrations How are processes of vision, perception, and sensation conceived in the Renaissance? How are those conceptions made manifest in the arts? The essays in this volume address these and similar questions to establish important theoretical and philosophical bases for artistic production in the Renaissance and beyond. The essays also attend to the views of historically significant writers from the ancient classical period to the eighteenth century, including Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus, St Augustine, Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), Ibn Sahl, Marsilio Ficino, Nicholas of Cusa, Leon Battista Alberti, Gian Paolo Lomazzo, Gregorio Comanini, John Davies, Rene Descartes, Samuel van Hoogstraten, and George Berkeley. Contributors carefully scrutinize and illustrate the effect of changing and evolving ideas of intellectual and physical vision on artistic practice in Florence, Rome, Venice, England, Austria, and the Netherlands. The artists whose work and practices are discussed include Fra Angelico, Donatello, Leonardo da Vinci, Filippino Lippi, Giovanni Bellini, Raphael, Parmigianino, Titian, Bronzino, Johannes Gumpp and Rembrandt van Rijn. Taken together, the essays provide the reader with a fresh perspective on the intellectual confluence between art, science, philosophy, and literature across Renaissance Europe. Contents Introduction, John S. Hendrix and Charles H. Carman; Classical optics and the perspectivae traditions leading to the Renaissance, Nader El-Bizri; Meanings of perspective in the Renaissance: tensions and resolution, Charles H. -

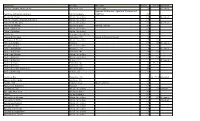

Offner Artist List Offner Artists Web.Xls Folder Title Heading DLI Name Box

OffnerFolder Artisttitle List Heading OffnerDLI artists name web.xls Box no. Box no. Oversized Adimari Cassoni, Master of the Florentine, 15c Lo Scheggia 93 Oversized Agostino di Giovanni (Agnolo di Ventura filed Agostino and Agnolo da Siena Italian Sculpture with him) 209 Alamanno, Pietro Italian, 16c or later 135 Oversized Alberti, Antonio (Antonio da Ferrara) Italian, 16c or later 135 Albertinelli, Mariotto Italian, 16c or later 135 Oversized Alberto di Arnoldo Italian Sculpture Arnoldi, Alberto 209 Allori, Alessandro Italian, 16c or later 135 Allori, Cristofano Italian, 16c or later 135 Altichiero Venetian, 14-early 15c 39 Alunno di Bennozo Florentine, 15c Alesso di Benozzo Gozzoli 93 Ambrogio de Predis Italian, 16c or later 135 187 Amico di Sandro Portraits 187 207 Oversized Amigoni, Jacopo Italian, 16c or later 135 Andrea da Bologna Bolognese, 14c 30 Oversized Andrea da Firenze Florentine 14c 60 187 Andrea da Murano Italian, 16c or later 135 Andrea del Sarto Italian, 16c or later 135 187 Andrea di Bartolo Sienese, 14c 9 Oversized Andrea di Cione Florentine 14c 84 85, 211 Andrea di Giusto Florentine, 15c 93 Andrea di Jacopo d'Ognabene Italian Sculpture 209 Andrea di Niccolo Sienese, 15c 87 Angelico, Fra Florentine, 15c 93 94, 95, 96 Oversized Angelo di Puccinelli Lucchese, 14c 23 Angers 1310 Pistoia, 13-14c Master of 1310 28 Anguissola, Sofonisba Portraits 187 Oversized Ansuino da Forlì Italian, 16c or later 135 187 Portraits Antelami, Benedetto Italian Sculpture 209 Antico Italian Sculpture 209 Antonello da Messina Italian, 16c or -

Agnolo Gaddi

Frammentiarte.it vi offre l'opera completa ed anche il download in ordine alfabetico per ogni singolo artista Giorgio Vasari - Le vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri (1568) Parte prima Agnolo Gaddi VITA D’AGNOLO GADDI PITTOR FIORENTINO Di quanto onore e utile sia l’essere eccellente in un’arte nobile, manifestamente si vide nella virtù e nel governo di Taddeo Gaddi, il quale, essendosi procacciato con la industria e fatiche sue oltre al nome buonissime faccultà, lasciò in modo accomodate le cose della famiglia sua, quando passò all’altra vita, che agevolmente potettono Agnolo e Giovanni suoi figliuoli dar poi principio a grandissime ricchezze et all’esaltazione di casa Gaddi, oggi in Fiorenza nobilissima et in tutta la cristianità molto reputata. E di vero è ben stato ragionevole, avendo ornato Gaddo, Taddeo, Agnolo e Giovanni colla virtù e con l’arte loro molte onorate chiese, che siano poi stati i loro successori dalla S. Chiesa Romana e da’ sommi Pontefici di quella, ornati delle maggiori dignità ecclesiastiche. Taddeo dunque, del quale avemo di sopra scritto la vita, lasciò Agnolo e Giovanni suoi figliuoli in compagnia di molti suoi discepoli, sperando che particolarmente Agnolo dovesse nella pittura eccellentissimo divenire; ma egli, che nella sua giovanezza mostrò volere di gran lunga superare il padre, non riuscì altramente secondo l’openione che già era stata di lui conceputa, perciò che, essendo nato e alevato negl’agi, che sono molte volte d’impedimento agli studii, fu dato più ai traffichi e alle mercanzie che all’arte della pittura. -

Report on an Imperial Mission to Milan 1447 by Enea Silvio Piccolomini

Report on an Imperial mission to Milan 1447 by Enea Silvio Piccolomini. Edited and translated by Michael von Cotta-Schönberg. 3rd preliminary version. (Reports on Five Diplomatic Missions by Enea Silvio Piccolomini; 2) Michael Von Cotta-Schönberg To cite this version: Michael Von Cotta-Schönberg. Report on an Imperial mission to Milan 1447 by Enea Silvio Piccolo- mini. Edited and translated by Michael von Cotta-Schönberg. 3rd preliminary version. (Reports on Five Diplomatic Missions by Enea Silvio Piccolomini; 2). 2020. hal-02557959v3 HAL Id: hal-02557959 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02557959v3 Submitted on 3 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. (Reports on FiveDiplomatic Missions by Enea Silvio Piccolomini; 2) 0 Report on an Imperial Mission to Milan 1447 by Enea Silvio Piccolomini. Edited and translated by Michael von Cotta-Schönberg 3rd version 2021 1 Abstract At the death of Duke Filippo Maria Visconti of Milan in 1447, the House of Visconti became extinct. Among the pretenders to the Visconti heritage was Emperor Friedrich III who, with some justice, claimed that Milan was an imperial feud that had now reverted to the Empire. -

Castelli, Rocche E Torri

“Popoli abituati da secoli a governarsi da sé, “Populations for centuries used to governing popoli ricchi di tradizioni proprie, sviluppatesi themselves, rich populations with their own in lunghi secoli di vita politica autonoma, popo- traditions, developed over centuries of independent li disciplinati nel loro spirito di libertà, …”. political life, populations that are disciplined in their (Emile Chanoux, da “Federalismo e Autonomie”, freedom…”. 1943). (Emile Chanoux, from “Federalism and Autonomy”, 1943). La provincia di Varese è territorio di frontiera, con- The province of Varese is a borderland that was tesa dalle moltissime signorie del luogo tra l’XI e il contended by many seignories between the 11th XV secolo. I castelli e le torri di segnalazione and 15th centuries. It is a land dotted with castles segnano il territorio profondamente. Hanno ormai and lookout towers that have now lost their role as perduto le caratteristiche di strutture difensive, defensive structures, becoming “delightful villas” for diventando " ville di delizie " per lo svago dei the lords that built them. Nevertheless, due to the signori che le avevano edificate. Ma proprio per la very fact that they mark the territory, they represent caratteristica di aver segnato il territorio, costitui- a still visible system that shapes a land of lakes, scono un sistema ancora percepibile, che dà plains and mountains and bear witness to the wealth forma alla terra situata tra laghi, pianure e monta- and industriousness of the past. gne, a testimonianza della ricchezza e della labo- riosità del passato. Castiglione Olona: La Collegiata Affreschi di Masolino da Panicale 1 ANGERA Rocca Borromeo (Info: 0331 931300) La Rocca sorge su uno sperone roccioso in vista Rocca Borromeo of Angera di Arona, del Lago Maggiore e del territorio vare- sino. -

Tarot Art & History 14 Day Tour of Northern Italy

Tour Managers: Arnell Ando & Michael Tarot Art & History 14 Day McAteer with Morena Poltronieri & Ernesto Fazioli of Museo dei Tarocchi ★ ★ Tour of Northern Italy Tour Contact Information th th Sunday April 12 – 26 2015 Hotel Florida, Milan Day 1: April 12th Arrive in Milan In: April 12th 2015 15:00 - 17:30 Hotel Check-in & Tour Registration Out: April 13th 2015 with hosts Arnell, Michael, Morena & Ernesto. Join us for Address: Via Lepetit, 33, 20124, Milano dinner and meet our merry band of tarot travelers. Tel: (+39) 02-6705921 (D) {D=Dinner B=Breakfast} www.hotelfloridamilan.com - [email protected] Hotel Santo Stefano, Ferrara th In: April 13 2015 th Visconti/Sforza Cards - Accademia Carrara Out: April 16 2015 Via Boccacanale di Santo Stefano, 21, 44121, Ferrara Day 11: April 22nd Bergamo – Accademia Carrara Tel: (+39) 0532/242348 or 0532/206924 A private viewing of original Visconti/Sforza Tarocchi cards (from www.hotelsantostefanofe.it - [email protected] 1450, oldest known deck by Bonifacio Bembo) at the Accademia Carrara . Lunch. Explore around and have a nice group dinner nearby. Together Inn, Florence (B, D) In: April 16th 2015 th Out: April 17 2015 Via A. De Gasperi, 6, 50012 Bagno a Ripoli, Florence Tel: (+39) 0556822000 - Cell: (+39) 3279365285 www.togetherflorenceinn.com - [email protected] Executive Hotel, Siena In: April 17th 2015 Out: April 20th 2015 Via Nazzareno Orlandi 32, 53100 Siena Ancient Tarot Fresco near Castello di Masnago Tel: (+39) 0577331210 rd Day 12: April 23 Bergamo – Partia – Milan www.executivehotelsiena.com - [email protected] After hotel check-out, we’ll travel to Partia and picnic near Castello di Masnago. -

Cennino Cennini

Rudolf Kuhn Cennino Cennini Sein Verständnis dessen, was die Kunst in der Malerei sei, und seine Lehre vom Entwurfs- und vom Werkprozeß1 (Zuerst gedruckt in: Zeitschrift für Ästhetik und Allgemeine Kunstwissenschaft vol. 36, 1991, 104 – 153; die Seitenumbrüche dieser Druckausgabe sind in Klammern angegeben) Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung 3 I. Der Libro dell'Arte ist ein Lehrbuch der Kunst 4 1. Das Lehrbuch der Kunst enthält einen Lehrgang 5 2. Vom Inhalt des Lehrganges der Kunst und die Aufzählung der Aufgaben der Kunst in der Malerei 6 3. Die Länge der Ausbildung eines Künstlers 8 II. Storia und Componere 8 1. Storia 9 2. Componere 10 3. Lehrte Cennini, vorbereitend auf dem Papier zu entwerfen oder zeichnend auf dem Bildträger (Wand oder Tafel)? 12 3,1. Was ergibt sich aus seinem Lehrbuch der Kunst? 12 3,2. Und die erhaltenen Ureinfälle, Skizzen und abschließenden Reinzeichnungen? 14 4. Entwurfsprozess auf dem Bildträger 18 4,1. Der Entwurf auf der Wand 18 4,2. Der Entwurf auf der Tafel 20 5. Hell-dunkel und Farbe 21 5,1. Die sieben Farben 21 5,2. Die Abstufung (digradazione) der Farben sowie des Hell und Dunkels 22 6. Proportionen, Räumliche Verhältnisse, Perspektiven 26 6,1. Die Maßrechnung 26 6,2. Die Frage nach den Proportionen der Körper von Mann, Frau und Tier 27 1 Im Rahmen eines Akademiestipendiums der Stiftung Volkswagen konnte ich u.a. dieses Kapitel einer Abhandlungsfolge fertigstellen. Ich danke der Stiftung Volkswagen dafür sehr. 6,3. Die räumlichen Verhältnisse bei Figur und Storia 27 6,4. Die Perspektive 28 III. Studien 28 1. -

The Battle of Pavia 1525" (Visconti Castle, Pavia, June–November 2015) Associated Event of Expo 2015 in Milan, Italy

AComIn participates in the Exhibition "The Battle of Pavia 1525" (Visconti Castle, Pavia, June–November 2015) Associated event of Expo 2015 in Milan, Italy The AComIn project provides 3D restoration of historical events for the exhibition "The Battle of Pavia 1525". The novel IT approach to bring cultural heritage artifacts closer to people is implemented jointly with the Computer Vision and Multimedia Lab of Pavia University, headed by Prof. Virginio Cantoni. The Battle of Pavia is the decisive engagement of the Italian War (1521-1526) where France fights against Spain and the Holy Roman Empire for dominance in Italy. More than 10,000 knights and 40,000 soldiers took part in the battle; for the first time small arms were successfully used. The Exhibition shows a famous original medieval tapestry dedicated to the battle as well as multimedia presentations of six other large tapestries and several IT applications (eye tracker, avatar, 3D figures, 3D tactile matrices) that demonstrate modern digitised presentations of the tapestries and their main characters. The exhibition is located in the historic Visconti Castle in Pavia and will be open till November 2015. Visconti Castle in Pavia – the location of the exhibition One of the original tapestries on the Battle of Pavia, created in 1528-1530 (9x4 m, brought from Naples for the Exhibition in Pavia) IICT-BAS participates in the exhibition with 3D figures of historical characters from the Battle of Pavia, printed on the AComIn 3D printer using 3D models created by students and members of the Computer Vision and Multimedia Lab of Pavia University.