The Type 45 Daring-Class Destroyer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

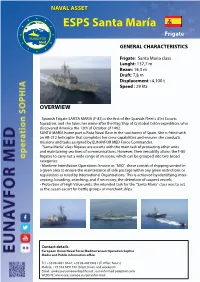

ESPS Santa María Frigate EUNAVFOR Med GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

NAVAL ASSET ESPS Santa María Frigate EUNAVFOR Med GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS Frigate: Santa Maria class Lenght: 137,7 m Beam: 14,3 m Draft: 7,8 m Displacement : 4,100 t Speed : 29 kts OVERWIEW Spanish Frigate SANTA MARÍA (F-81) is the first of the Spanish Fleet’s 41st Escorts Squadron, and she takes her name after the Flag Ship of Cristobal Colón expedition, who discovered America the 12th of October of 1492. SANTA MARÍA home port is Rota Naval Base in the southwest of Spain. She is fitted with an AB-212 helicopter that completes her crew capabilities and ensures she conducts missions and tasks assigned by EUNAVFOR MED Force Commander. “Santa María” class frigates are escorts with the main task of protecting other units and maintaining sea lines of communications. However, their versatility allows the F-80 frigates to carry out a wide range of missions, which can be grouped into two broad categories: • Maritime Interdiction Operations: known as “MIO”, these consist of shipping control in a given area to ensure the maintenance of safe passage within any given restrictions or regulations as ruled by International Organisations. This is achieved by identifying, inter- cepting, boarding, searching, and if necessary, the detention of suspect vessels; • Protection of High Value units: the intended task for the “Santa Maria” class was to act as the ocean escort for battle groups or merchant ships. Contact details European Union Naval Force Mediterranean Operation Sophia Media and Public information office Tel: +39 06 4691 9442 ; +39 06 46919451 (IT Office hours) Mobile: +39 334 6891930 (Silent hours and weekend) Email: [email protected] ; [email protected] WEBSITE: www.eeas.europa.eu/eunavfor-med. -

USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form Summary The USS Constellation’s career in naval service spanned one hundred years: from commissioning on July 28, 1855 at Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia to final decommissioning on February 4, 1955 at Boston, Massachusetts. (She was moved to Baltimore, Maryland in the summer of 1955.) During that century this sailing sloop-of-war, sometimes termed a “corvette,” was nationally significant for its ante-bellum service, particularly for its role in the effort to end the foreign slave trade. It is also nationally significant as a major resource in the mid-19th century United States Navy representing a technological turning point in the history of U.S. naval architecture. In addition, the USS Constellation is significant for its Civil War activities, its late 19th century missions, and for its unique contribution to international relations both at the close of the 19th century and during World War II. At one time it was believed that Constellation was a 1797 ship contemporary to the frigate Constitution moored in Boston. This led to a long-standing controversy over the actual identity of the Constellation. Maritime scholars long ago reached consensus that the vessel currently moored in Baltimore is the 1850s U.S. navy sloop-of-war, not the earlier 1797 frigate. Describe Present and Historic Physical Appearance. The USS Constellation, now preserved at Baltimore, Maryland, was built at the navy yard at Norfolk, Virginia. -

Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress Ronald O'Rourke Specialist in Naval Affairs February 3, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32109 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress Summary Procurement of Arleigh Burke (DDG-51) class Aegis destroyers resumed in FY2010 after a four- year hiatus. Congress funded the procurement of one DDG-51 in FY2010, two in FY2011, and one more in FY2012. The Navy’s FY2012 budget submission calls for procuring seven more in FY2013-FY2016. DDG-51s to be procured through FY2015 are to be of the current Flight IIA design. The Navy wants to begin procuring a new version of the DDG-51 design, called the Flight III design, starting in FY2016. The Flight III design is to feature a new and more capable radar called the Air and Missile Defense Radar (AMDR). The Navy began preliminary design work on the Flight III DDG-51 in FY2012. The Navy wants to use a multiyear procurement (MYP) contract for DDG- 51s to be procured from FY2013 through FY2017. The Navy’s proposed FY2012 budget requested $1,980.7 million in procurement funding for the DDG-51 planned for procurement in FY2012. This funding, together with $48.0 million in advance procurement funding provided in FY2011, would complete the ship’s total estimated procurement cost of $2,028.7 million. The Navy’s proposed FY2012 budget also requested $100.7 million in advance procurement funding for two DDG-51s planned for procurement in FY2013, $453.7 million in procurement funding to help complete procurement costs for the three Zumwalt (DDG-1000) class destroyers that were procured in FY2007 and FY2009, and $166.6 million in research and development funding for the AMDR. -

Guns Blazing! Newsletter of the Naval Wargames Society No

All Guns Blazing! Newsletter of the Naval Wargames Society No. 290 – DECEMBER 2018 Extract from President Roosevelt’s, “Fireside Chat to the Nation”, 29 December 1940: “….we cannot escape danger by crawling into bed and pulling the covers over our heads……if Britain should go down, all of us in the Americas would be living at the point of a gun……We must produce arms and ships with every energy and resource we can command……We must be the great arsenal of democracy”. oOoOoOoOoOoOoOo The Poppies of four years ago at the Tower of London have been replaced by a display of lights. Just one of many commemorations around the World to mark one hundred years since the end of The Great War. Another major piece of art, formed a focal point as the UK commemorated 100 years since the end of the First World War. The ‘Shrouds of the Somme’ brought home the sheer scale of human sacrifice in the battle that came to epitomize the bloodshed of the 1914-18 war – the Battle of the Somme. Artist Rob Heard hand stitched and bound calico shrouds for 72,396 figures representing British Commonwealth servicemen killed at the Somme who have no known grave, many of whose bodies were never recovered and whose names are engraved on the Thiepval Memorial. Each figure of a human form, was individually shaped, shrouded and made to a name. They were laid out shoulder to shoulder in hundreds of rows to mark the Centenary of Armistice Day at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park from 8-18th November 2018 filling an area of over 4000 square metres. -

MEDICINE DISPOSAL PRODUCTS an Overview of Products & Performance Questions

MEDICINE DISPOSAL PRODUCTS an overview of products & performance questions Community Environmental Health Strategies LLC March Produced for San Francisco Department of the Environment 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Glossary of Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Overview of Products and Questions Examined ..................................................................................... 5 II. Medicine Disposal Background ................................................................................................................... 8 A. Medicine Disposal Guidelines and Regulations............................................................................................... 8 B. DEA’s non-retrievable standard for controlled substances .................................................................... 10 C. Disposal of waste pharmaceuticals from households................................................................................ 11 D. Disposal of waste pharmaceuticals by the healthcare sector and regulated generators ........... 17 III. Medicine Disposal Products: Performance Questions & Available Product Testing ............ 23 A. Performance Questions ......................................................................................................................................... -

CRUISE MISSILE THREAT Volume 2: Emerging Cruise Missile Threat

By Systems Assessment Group NDIA Strike, Land Attack and Air Defense Committee August 1999 FEASIBILITY OF THIRD WORLD ADVANCED BALLISTIC AND CRUISE MISSILE THREAT Volume 2: Emerging Cruise Missile Threat The Systems Assessment Group of the National Defense Industrial Association ( NDIA) Strike, Land Attack and Air Defense Committee performed this study as a continuing examination of feasible Third World missile threats. Volume 1 provided an assessment of the feasibility of the long range ballistic missile threats (released by NDIA in October 1998). Volume 2 uses aerospace industry judgments and experience to assess Third World cruise missile acquisition and development that is “emerging” as a real capability now. The analyses performed by industry under the broad title of “Feasibility of Third World Advanced Ballistic & Cruise Missile Threat” incorporate information only from unclassified sources. Commercial GPS navigation instruments, compact avionics, flight programming software, and powerful, light-weight jet propulsion systems provide the tools needed for a Third World country to upgrade short-range anti-ship cruise missiles or to produce new land-attack cruise missiles (LACMs) today. This study focuses on the question of feasibility of likely production methods rather than relying on traditional intelligence based primarily upon observed data. Published evidence of technology and weapons exports bears witness to the failure of international agreements to curtail cruise missile proliferation. The study recognizes the role LACMs developed by Third World countries will play in conjunction with other new weapons, for regional force projection. LACMs are an “emerging” threat with immediate and dire implications for U.S. freedom of action in many regions . -

Operation Nickel Grass: Airlift in Support of National Policy Capt Chris J

Secretary of the Air Force Janies F. McGovern Air Force Chief of Staff Gen Larry D. Welch Commander, Air University Lt Gen Ralph Lv Havens Commander, Center for Aerospace Doctrine, Research, and Education Col Sidney J. Wise Editor Col Keith W. Geiger Associate Editor Maj Michael A. Kirtland Professional Staff Hugh Richardson. Contributing Editor Marvin W. Bassett. Contributing Editor John A. Westcott, Art Director and Production Mu linger Steven C. Garst. Art Editor and Illustrator The Airpower Journal, published quarterly, is the professional journal of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for presenting and stimulating innovative thinking on military doctrine, strategy, tactics, force structure, readiness, and other national defense matters. The views and opinions ex- pressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as car- rying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, the Air Force, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. Articles in this edition may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If repro- duced, the Airpower Journal requests a cour- tesy line. JOURNAL SPRING 1989. Vol. Ill, No. I AFRP 50 2 Editorial 2 Air Interdiction Col Clifford R. Kxieger, USAF 4 Operation Nickel Grass: Airlift in Support of National Policy Capt Chris J. Krisinger, USAF 16 Paradox of the Headless Horseman Lt Col Joe Boyles, USAF Capt Greg K. Mittelman, USAF 29 A Rare Feeling of Satisfaction Maj Michael A. Kirtland, USAF 34 Weaseling in the BUFF Col A. Lee Harrell, USAF 36 Thinking About Air Power Maj Andrew J. -

![D 32 Daring [Type 45 Batch 1] - 2011](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4772/d-32-daring-type-45-batch-1-2011-594772.webp)

D 32 Daring [Type 45 Batch 1] - 2011

D 32 Daring [Type 45 Batch 1] - 2011 United Kingdom Type: DDG - Guided Missile Destroyer Max Speed: 28 kt Commissioned: 2011 Length: 152.4 m Beam: 21.2 m Draft: 7.4 m Crew: 190 Displacement: 7450 t Displacement Full: 8000 t Propulsion: 2x Wärtsilä 12V200 Diesels, 2x Rolls-Royce WR-21 Gas Turbines, CODOG Sensors / EW: - Type 1045 Sampson MFR - Radar, Radar, Air Search, 3D Long-Range, Max range: 398.2 km - Type 2091 [MFS 7000] - Hull Sonar, Active/Passive, Hull Sonar, Active/Passive Search & Track, Max range: 29.6 km - Type 1047 - (LPI) Radar, Radar, Surface Search & Navigation, Max range: 88.9 km - UAT-2.0 Sceptre XL - (Upgraded, Type 45) ESM, ELINT, Max range: 926 km - IRAS [CCD] - (Group, IR Alerting System) Visual, LLTV, Target Search, Slaved Tracking and Identification, Max range: 185.2 km - IRAS [IR] - (Group, IR Alerting System) Infrared, Infrared, Target Search, Slaved Tracking and Identification Camera, Max range: 185.2 km - IRAS [Laser Rangefinder] - (Group, IR Alerting System) Laser Rangefinder, Laser Rangefinder, Max range: 0 km - Type 1046 VSR/LRR [S.1850M, BMD Mod] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Radar, Radar, Air Search, 3D Long-Range, Max range: 2000.2 km - Radamec 2500 [EO] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Visual, Visual, Weapon Director & Target Search, Tracking and Identification TV Camera, Max range: 55.6 km - Radamec 2500 [IR] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Infrared, Infrared, Weapon Director & Target Search, Tracking and Identification Camera, Max range: 55.6 km - Radamec 2500 [Laser Rangefinder] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Laser Rangefinder, Laser Rangefinder for Weapon Director, Max range: 7.4 km - Type 1048 - (LPI) Radar, Radar, Surface Search w/ OTH, Max range: 185.2 km Weapons / Loadouts: - Aster 30 PAAMS [GWS.45 Sea Viper] - Guided Weapon. -

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress September 16, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32665 Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The current and planned size and composition of the Navy, the annual rate of Navy ship procurement, the prospective affordability of the Navy’s shipbuilding plans, and the capacity of the U.S. shipbuilding industry to execute the Navy’s shipbuilding plans have been oversight matters for the congressional defense committees for many years. In December 2016, the Navy released a force-structure goal that calls for achieving and maintaining a fleet of 355 ships of certain types and numbers. The 355-ship goal was made U.S. policy by Section 1025 of the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2810/P.L. 115- 91 of December 12, 2017). The Navy and the Department of Defense (DOD) have been working since 2019 to develop a successor for the 355-ship force-level goal. The new goal is expected to introduce a new, more distributed fleet architecture featuring a smaller proportion of larger ships, a larger proportion of smaller ships, and a new third tier of large unmanned vehicles (UVs). On June 17, 2021, the Navy released a long-range Navy shipbuilding document that presents the Biden Administration’s emerging successor to the 355-ship force-level goal. The document calls for a Navy with a more distributed fleet architecture, including 321 to 372 manned ships and 77 to 140 large UVs. A September 2021 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report estimates that the fleet envisioned in the document would cost an average of between $25.3 billion and $32.7 billion per year in constant FY2021 dollars to procure. -

The Cost of the Navy's New Frigate

OCTOBER 2020 The Cost of the Navy’s New Frigate On April 30, 2020, the Navy awarded Fincantieri Several factors support the Navy’s estimate: Marinette Marine a contract to build the Navy’s new sur- face combatant, a guided missile frigate long designated • The FFG(X) is based on a design that has been in as FFG(X).1 The contract guarantees that Fincantieri will production for many years. build the lead ship (the first ship designed for a class) and gives the Navy options to build as many as nine addi- • Little if any new technology is being developed for it. tional ships. In this report, the Congressional Budget Office examines the potential costs if the Navy exercises • The contractor is an experienced builder of small all of those options. surface combatants. • CBO estimates the cost of the 10 FFG(X) ships • An independent estimate within the Department of would be $12.3 billion in 2020 (inflation-adjusted) Defense (DoD) was lower than the Navy’s estimate. dollars, about $1.2 billion per ship, on the basis of its own weight-based cost model. That amount is Other factors suggest the Navy’s estimate is too low: 40 percent more than the Navy’s estimate. • The costs of all surface combatants since 1970, as • The Navy estimates that the 10 ships would measured per thousand tons, were higher. cost $8.7 billion in 2020 dollars, an average of $870 million per ship. • Historically the Navy has almost always underestimated the cost of the lead ship, and a more • If the Navy’s estimate turns out to be accurate, expensive lead ship generally results in higher costs the FFG(X) would be the least expensive surface for the follow-on ships. -

![D 32 Daring [Type 45 Batch 1] - 2015 Harpoon](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6950/d-32-daring-type-45-batch-1-2015-harpoon-726950.webp)

D 32 Daring [Type 45 Batch 1] - 2015 Harpoon

D 32 Daring [Type 45 Batch 1] - 2015 Harpoon United Kingdom Type: DDG - Guided Missile Destroyer Max Speed: 28 kt Commissioned: 2015 Length: 152.4 m Beam: 21.2 m Draft: 7.4 m Crew: 190 Displacement: 7450 t Displacement Full: 8000 t Propulsion: 2x Wärtsilä 12V200 Diesels, 2x Rolls-Royce WR-21 Gas Turbines, CODOG Sensors / EW: - Type 1045 Sampson MFR - Radar, Radar, Air Search, 3D Long-Range, Max range: 398.2 km - Type 2091 [MFS 7000] - Hull Sonar, Active/Passive, Hull Sonar, Active/Passive Search & Track, Max range: 29.6 km - Type 1047 - (LPI) Radar, Radar, Surface Search & Navigation, Max range: 88.9 km - UAT-2.0 Sceptre XL - (Upgraded, Type 45) ESM, ELINT, Max range: 926 km - IRAS [CCD] - (Group, IR Alerting System) Visual, LLTV, Target Search, Slaved Tracking and Identification, Max range: 185.2 km - IRAS [IR] - (Group, IR Alerting System) Infrared, Infrared, Target Search, Slaved Tracking and Identification Camera, Max range: 185.2 km - IRAS [Laser Rangefinder] - (Group, IR Alerting System) Laser Rangefinder, Laser Rangefinder, Max range: 0 km - Type 1046 VSR/LRR [S.1850M, BMD Mod] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Radar, Radar, Air Search, 3D Long-Range, Max range: 2000.2 km - Radamec 2500 [EO] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Visual, Visual, Weapon Director & Target Search, Tracking and Identification TV Camera, Max range: 55.6 km - Radamec 2500 [IR] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Infrared, Infrared, Weapon Director & Target Search, Tracking and Identification Camera, Max range: 55.6 km - Radamec 2500 [Laser Rangefinder] - (RAN-40S, RAT-31DL, SMART-L Derivative) Laser Rangefinder, Laser Rangefinder for Weapon Director, Max range: 7.4 km - Type 1048 - (LPI) Radar, Radar, Surface Search w/ OTH, Max range: 185.2 km Weapons / Loadouts: - Aster 30 PAAMS [GWS.45 Sea Viper] - Guided Weapon. -

UK Maritime Power

Joint Doctrine Publication 0-10 UK Maritime Power Fifth Edition Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre Joint Doctrine Publication 0-10 UK Maritime Power Joint Doctrine Publication 0-10 (JDP 0-10) (5th Edition), dated October 2017, is promulgated as directed by the Chiefs of Staff Director Concepts and Doctrine Conditions of release 1. This information is Crown copyright. The Ministry of Defence (MOD) exclusively owns the intellectual property rights for this publication. You are not to forward, reprint, copy, distribute, reproduce, store in a retrieval system, or transmit its information outside the MOD without VCDS’ permission. 2. This information may be subject to privately owned rights. i Authorisation The Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre (DCDC) is responsible for publishing strategic trends, joint concepts and doctrine. If you wish to quote our publications as reference material in other work, you should confirm with our editors whether the particular publication and amendment state remains authoritative. We welcome your comments on factual accuracy or amendment proposals. Please send them to: The Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre Ministry of Defence Shrivenham SWINDON Wiltshire SN6 8RF Telephone: 01793 31 4216/4217/4220 Military network: 96161 4216/4217/4220 E-mail: [email protected] All images, or otherwise stated are: © Crown copyright/MOD 2017. Distribution Distributing Joint Doctrine Publication (JDP) 0-10 (5th Edition) is managed by the Forms and Publications Section, LCSLS Headquarters and Operations Centre, C16 Site, Ploughley Road, Arncott, Bicester, OX25 1LP. All of our other publications, including a regularly updated DCDC Publications Disk, can also be demanded from the LCSLS Operations Centre.