First-Person Shooter Games As a Way of Connecting to People: ‘‘Brothers in Blood’’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The PLATO System : a Study in the Diffusion of an Innovation

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1987 The PLATO system : a study in the diffusion of an innovation. Francis D. Driscoll University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Driscoll, Francis D., "The PLATO system : a study in the diffusion of an innovation." (1987). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4265. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4265 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PLATO SYSTEM: A STUDY IN THE DIFFUSION OF AN INNOVATION A Dissertation Presented By Francis D. Driscoll Submitted to the Graduate School of the versity of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION September 1987 School of Education © Copyright by Francis D. Driscoll 1987 All Rights Reserved THE PLATO SYSTEM: A STUDY IN THE DIFFUSION OF AN INNOVATION A Dissertation Presented By FRANCIS D. DRISCOLL Approved as to style and content by; C William C. Wolf, Ji^., chairperson of Committee 1 \ -7 Klaus Schultz, Member / ;; /I Z Conrad A. Wogrin, Member George urch,Meeting''Ch.wtinq Dean School of Education ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study required the cooperation of many people. I am grateful to iny committee for their willingness to serve and help. Special thanks go to Bill Wolf for his guidance, enthusiasm and responsiveness to my efforts. -

ED158767.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 158 767 IR 006 398 AUTHOR Slattow, G., Ed. TITLE ,1 Demonstration of the PLATO IV Computer-Based Education System. Final Report: January 1, 1972-June 30, 1976. INSTITUTION Illinois Univ., Urbana. Computer-Based Education Lab. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Mar 77 k, CONTRACT NSF-C-723 NOTE 4tep. AVAILARLEFROM Computer-based Education Research Laboratory, University Of. Illinois, Urbana, Illinois ($7.70) EDRS PRICE. MF-$0.83 HC-$22.09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS College-Programs; *Computer Assisted Instruction; *Curriculum Development; Elementary School Mathematics; Formative Evaluatidn; Higher Education; *Instrpttional Design; Interinstitutional CoopeRation; Man Machine Systems; Networks; On/rine System's; Publications; Reading Instruction; *Systems Development; Tables (Data) IDENTIFIERS *PLATO. IV ABSTRACT This report for the period January 1,:1972 to June 30, 1976 describes a program conducted to reach the following major objectives: (1) to develop, test, and operate -a large geographically dispersed PLATO IV network; q2) to implement an educational prograda involving educational liaison, teacher/author training, curriculum -planning, an& materials development; (3) to carry out a two-year field, test and demonstration; and (4) to develop plans and strategies and assisi in a systematic evaluation of the educational effectiveness of the 'PLATO IV system. Chaptef t gives a brief account 'of PLATO history, a summary of the program, and n discussion,of,the results and. their impliCations, Chapter 2 describes the methods by which the PLATO Service Organization provides authoatraining, -liaison,' documentation, and other services to.a larTe User community. Chapter 3 provides evaluation of system reliability, performance, 'use, .and-educational effectiveness, and presents a detailed case study in elementary mathematics. -

Definitions of “Role-Playing Games”

This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge in Role- Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations on April 4, 2018, available online: https://www.routledge.com/Role-Playing-Game-Studies-Transmedia-Foundations/Deterding-Zagal/p/book/9781138638907 Please cite as: Zagal, José P. and Deterding, S. (2018). Definitions of “Role-Playing Games”. In Zagal, José P. and Deterding, S. (eds.), Role-Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations. New York: Routledge, 19-51. 2 Definitions of “Role-Playing Games” José P. Zagal; Sebastian Deterding For some, defining “game” is a hopeless task (Parlett 1999). For others, the very idea that one could capture the meaning of a word in a list of defining features is flawed, because language and meaning-making do not work that way (Wittgenstein 1963). Still, we use the word “game” every day and, generally, understand each other when we do so. Among game scholars and professionals, we debate “game” definitions with fervor and sophistication. And yet, while we usually agree with some on some aspects, we never seem to agree with everyone on all. At most, we agree on what we disagree about – that is, what disagreements we consider important for understanding and defining “games” (Stenros 2014). What is true for “games” holds doubly for “role-playing games”. In fact, role- playing games (RPGs) are maybe the most contentious game phenomenon: the exception, the outlier, the not-quite-a-game game. In their foundational game studies text Rules of Play, Salen and Zimmerman (2004, 80) acknowledge that their definition of a game (“a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome”) considers RPGs a borderline case. -

PLATO (Computer System)

PLATO (computer system) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other uses, see Plato (disambiguation). PLATO was one of the first generalized computer assisted instruction systems, first widely used starting in the early 1970s. PLATO was originally built by the University of Illinois and ran for many years, both for in-university coursework as well as being remotely accessed by local schools. The project was later taken over by Control Data Corporation (CDC), who built the machines it ran on at the University. CDC President William Norris planned to make PLATO a major force in the computing world, and was a keystone of his ideas about corporate social responsibility. Although the project was economically a failure and supplanted by other technologies by the time the last production PLATO system was turned off in 2006, PLATO nevertheless pioneered key concepts such as online forums and message boards, online testing, email, chat rooms, picture languages, instant messaging, remote screen sharing, and multiplayer online games. The acronym PLATO stands for Programmed Logic for Automated Teaching Operations.[1][2] Contents • 1 Background • 2 PLATO's birth • 3 NSF involvement • 4 The CDC years • 5 PLATO in South Africa • 6 The PLATO Online Community • 7 Later efforts and other versions • 8 Cyber1 • 9 Innovation • 10 References • 11 External links Background Prior to the 1944 G.I. Bill, which provided free college education to returning World War II veterans, higher education was limited to a minority of the U.S. population. The trend towards much larger enrollment in higher education was clear by the early 1950s, and the problem of providing for an influx of new students was a serious concern. -

You've Seen the Movie, Now Play The

“YOU’VE SEEN THE MOVIE, NOW PLAY THE VIDEO GAME”: RECODING THE CINEMATIC IN DIGITAL MEDIA AND VIRTUAL CULTURE Stefan Hall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Committee: Ronald Shields, Advisor Margaret M. Yacobucci Graduate Faculty Representative Donald Callen Lisa Alexander © 2011 Stefan Hall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ronald Shields, Advisor Although seen as an emergent area of study, the history of video games shows that the medium has had a longevity that speaks to its status as a major cultural force, not only within American society but also globally. Much of video game production has been influenced by cinema, and perhaps nowhere is this seen more directly than in the topic of games based on movies. Functioning as franchise expansion, spaces for play, and story development, film-to-game translations have been a significant component of video game titles since the early days of the medium. As the technological possibilities of hardware development continued in both the film and video game industries, issues of media convergence and divergence between film and video games have grown in importance. This dissertation looks at the ways that this connection was established and has changed by looking at the relationship between film and video games in terms of economics, aesthetics, and narrative. Beginning in the 1970s, or roughly at the time of the second generation of home gaming consoles, and continuing to the release of the most recent consoles in 2005, it traces major areas of intersection between films and video games by identifying key titles and companies to consider both how and why the prevalence of video games has happened and continues to grow in power. -

SHARING DIGITAL RESOURCES: PLATO and the EMERGING ETHICS of SOCIAL COMPUTING Guillaume Latzko-Toth Université Laval

Please see citation and license information on the last page. SHARING DIGITAL RESOURCES: PLATO AND THE EMERGING ETHICS OF SOCIAL COMPUTING Guillaume Latzko-Toth Université Laval Steve Jones University of Illinois at Chicago Abstract This paper presents findings from our ongoing research on the genesis and evolution of early social software on one of the most influential platforms in social computing: PLATO, a pioneering educational and social computer platform developed at the Computer-based Education Research Laboratory (CERL) at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) in the 1960s and 1970s. Our research addresses the evolution of ethics in the emergent PLATO system. It examines the development of norms and establishment of areas of ethical concerns among developers and users of PLATO. Our hypothesis is that the social construction of norms and ethics occurs within the imaginary and real tensions among and between different actors of the sociotechnical system (students, teachers, system administrators). PLATO, as a prototypical participatory computer platform, provides a significant, early view of the extent to which the ethics of digital resources usage is socially and discursively constructed. This is particularly vivid in the discourse underlying the classification of system uses and applications between “disruptive” and “valuable”. As part of this project, we undertook digitizing archives of print-outs of the “general questions” forum used both by developers and users of PLATO IV from 1972 to 1976. A rhetorical analysis allowed us to identify a long-standing controversy about games and recreational uses of digital resources originally meant for other purposes. Considered disruptive by some, innovative and “functional” by others, these unanticipated uses paved the way to social computing and ultimately became the new “norm”. -

Encoding Monsters: “Ontology of the Enemy” and Containment of the Unknown in Role-Playing Games

The Philosophy of Computer Games Conference, Copenhagen 2018 Encoding monsters: “Ontology of the enemy” and containment of the unknown in role-playing games Jaroslav Švelch, University of Bergen Introduction From the ancient to contemporary cultures, monsters have embodied the fear of abnormality and the unknown (Cohen 1996; Henriksen et al. 2017). A prominent strand of monster scholarship emphasizes the fact that monsters confound our perceptive and cognitive abilities, and fill us with awe and terror (see Carroll 1990; Kristeva 1982; Cohen 1996). The philosopher Stephen Asma calls this approach the “sublime thesis,” based on Kant’s understanding of sublime (Asma 2012: 192). This sublime thesis can be understood as a normative yardstick of measuring monstrosity. But video games present us with a different kind of monster, a monster that is designed to be confronted and (usually) defeated by the player. Unlike the ideal “sublime” monster, it is encoded in computational systems and well defined in the game’s rules. Role-playing and action games like The Witcher 3 or God of War tend to contain whole hierarchies and databases of monsters that beckon us to figure them out, find their weak spots and defeat them. God of War’s draugar, for example, are a well-defined array of recurring enemy types with specific attack types and weaknesses, inspired by but very distinct from the draugar of Nordic myth, who embodied the fears of exclusion from local communities (Sayers 1996). To understand video game monsters, we must thus contrast the sublime thesis with a new theoretical approach, which captures the tendency to contain and encode monstrosity. -

PLATO (Computer System) 1 PLATO (Computer System)

PLATO (computer system) 1 PLATO (computer system) PLATO (Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations) [1][2] was the first (ca. 1960, on ILLIAC I) generalized computer assisted instruction system, and, by the late 1970s, comprised several thousand terminals worldwide on nearly a dozen different networked mainframe computers. Originally, PLATO was built by the University of Illinois and functioned for four decades, offering coursework (elementary–university) to UIUC students, local schools, and other universities. Several descendant systems still operate. The PLATO project was assumed by the Control Data Corporation (CDC), who built PLATO running a fractional distillation simulation. the machines with which PLATO operated at the University. CDC President William Norris planned to make PLATO a force in the computer world; the last production PLATO system was shut down in 2006 (coincidentally, just a month after Norris died), yet it established key on-line concepts: forums, message boards, online testing, e-mail, chat rooms, picture languages, instant messaging, remote screen sharing, and multi-player games. Historic background Before the 1944 G.I. Bill that provided free college education to World War II veterans, higher education was limited to a minority of the U.S. population. The trend towards greater enrollment notable by the early 1950s, and the problem of providing instruction for the many new students was a serious concern to university administrators. To wit, if computerised automation increased factory production, it could do the same for academic instruction. The USSR's 1957 launching of the Sputnik I artificial satellite energized the United States' government into spending more on science and engineering education. -

Definitions of Role-Playing Games

This is a repository copy of Definitions of Role-Playing Games. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/131407/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Zagal, José P. and Deterding, Christoph Sebastian orcid.org/0000-0003-0033-2104 (2018) Definitions of Role-Playing Games. In: Zagal, José P. and Deterding, Sebastian, (eds.) Role-Playing Game Studies. Routledge , pp. 19-52. Reuse ["licenses_typename_other" not defined] Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 2 Definitions of “Role-Playing Games” José P. Zagal; Sebastian Deterding For some, defining “game” is a hopeless task (Parlett 1999). For others, the very idea that one could capture the meaning of a word in a list of defining features is flawed, because language and meaning-making do not work that way (Wittgenstein 1963). Still, we use the word “game” every day and, generally, understand each other when we do so. Among game scholars and professionals, we debate “game” definitions with fervor and sophistication. And yet, while we usually agree with some on some aspects, we never seem to agree with everyone on all. At most, we agree on what we disagree about – that is, what disagreements we consider important for understanding and defining “games” (Stenros 2014). What is true for “games” holds doubly for “role-playing games”. In fact, role-playing games (RPGs) are maybe the most contentious game phenomenon: the exception, the outlier, the not-quite-a-game game. -

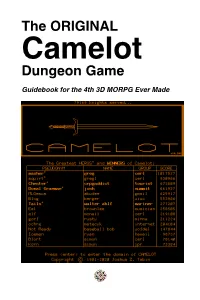

Camelot Guidebook V2.3

The ORIGINAL Camelot Dungeon Game Guidebook for the 4th 3D MORPG Ever Made The Original Camelot Dungeon Game Guidebook, v2.3 Copyright 2020 © Joshua Z. Tabin All Rights Reserved 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ______________________________________________________________3 Versions & Errata ______________________________________________________________4 History of Camelot & 3D MORPGs ________________________________________________5 Genesis of Dungeon Role Playing Games & Camelot ________________________________12 How to Play Camelot Today ____________________________________________________15 The PLATO Keyboard __________________________________________________________16 Configuring PTerm ____________________________________________________________18 Logging into Cyber1 __________________________________________________________21 Entering the Game ___________________________________________________________22 Learning to Play ______________________________________________________________26 Creang a Character __________________________________________________________28 Maps anD Following __________________________________________________________32 Your Character anD the Game Screen _____________________________________________34 Top-Right of Game Screen ______________________________________________________35 Top-LeS of Game Screen _______________________________________________________41 Center & BoUom of Game Screen ________________________________________________45 BoUom-Right – CarrieD Items ___________________________________________________47 -

Interview with Daniel M. Lawrence CRPG Pioneer and Author of Telengard June 22, 2007 by Matt Barton

Interview with Daniel M. Lawrence CRPG Pioneer and Author of Telengard June 22, 2007 By Matt Barton I recently had the great pleasure of interviewing Daniel Lawrence, a pioneer in the CRPG industry who started off writing CRPGs for mainframes. Perhaps his most famous CRPG is Telengard, which was one of the earliest (if not the earliest) game of its type for early platforms such as the Commodore PET, Atari 800, and TRS-80. It features "procedurally generated dungeons" so that no two games are exactly alike, and is set in real-time. Indeed, in many ways it's an early Diablo! In the interview below, I talk to Daniel about these early games and more general questions about what a good CRPG should be. The interview really helped me straighten out some important details about this historic game's development. Enjoy! Q: First off, I’m a bit confused about your work on earlier CRPGs. On your website, you state that you released a game called DND back in 1977, programming it in BASIC under the TOPS-10 operating system. Could you talk a bit more about your development of this game, such as what influenced you and what other CRPGs (or tabletop RPGs or wargames) influenced you? My research is rather sketchy on CRPGs available for mainframes during this era, so any information you can provide will be very helpful. A: Well certainly I had played Dungeons and Dragons™ the paper game put out just previously by TSR. DND as a game evolved from a simple beginning showing where your character was and grew, adding creatures, specials, better displays in response to the suggestions of the players at the ENAD (engineering administration building) at Purdue where I was a freshmen. -

Meta-Disciplines and Invisible Work, Featuring Dr. Paul Marty Journeys in Research, Ep

Meta-disciplines and Invisible Work, featuring Dr. Paul Marty Journeys in Research, Ep. 9 Recorded February 9, 2021 Evangeline Coker: Paul Marty, thank you so much for joining us today. Paul Marty: Thank you. It’s a real pleasure to be here. Evangeline Coker: So, you got an early start at being at the forefront of technological advancements. In the 1960s your father worked on the groundbreaking computer system and precursor of the internet PLATO, the first computer-based instructional system. And you as a child got to bring it home and test it out! What was that like? Paul Marty: I tell you, that really was something else. So, yes, my dad worked on the PLATO project at the University of Illinois. In fact, we moved to Champaign Urbana in 1972 when my dad, who was a pioneer in computer-based language learning technologies going way back to the 1950s, was recruited by the U of I to design and develop language lessons for PLATO. I should probably explain if you don’t know about PLATO, and by the way there were PLATO terminals at FSU in the 1970s, too, so people here might remember the system. PLATO was the world’s first network computer system for higher education. It was developed in the 1960s, and for a lot of people in the 1970s and the early ‘80s this was the internet. There’s a really good book on the history of PLATO called The Friendly Orange Glow by Brian Dear. It came out just a few years ago, and that book does a really good job of explaining some of PLATO’s unbelievable technological advancements for the time.