King Street Blues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brothers Under Fire Canadian Fire Fighters

The 1940s Society For Everyone Interested in Wartime Britain Issue 72 March / April 2012 £3.00 Blitz Kids Sean Longden on the Childrens war against Hitler Brothers Under Fire Canadian Fire Fighters. 2 part article by John Leete Lew Stone Jeff “Two-Tone Boogie” discovers more about this influential musician Diary Events and much more.... The 1940’s Society, 90 Lennard Road, Dunton Green, Sevenoaks, Kent TN13 2UX Tel: 01732 452505 Web: www.1940.co.uk Email: [email protected] 1 Enjoy Life The 1940s Society I don’t really follow football but I’m writing this after hearing that For Everyone Interested in Wartime Britain Fabrice Muamba remains in a critical condition in intensive care after suffering a cardiac arrest during the FA Cup tie at Tottenham. Regular meetings at Otford Memorial Hall near Sevenoaks A shock to all as he is a young fit 23 year old with no previous signs of health issues. Like many people I remember him in my prayers Friday 30th March 2012 - 8pm and wish him a speedy recovery. You may think it’s a rather sombre start to the magazine but I like to Blitz Kids think of it as a reminder of how fragile our lives are. A reminder that Britain’s children in the Second World War both we should make the most of what we have, smile, and take the time at home and on the front line to enjoy our lives. I’ve been reading the proofs of a book being published in June (Parachute Doctor) and you suddenly realise how Sean Longden death was such an everyday occurrence during the Second World War. -

George Chisholm

1 The TROMBONE of GEORGE CHISHOLM Solographer: Jan Evensmo Last update: March 9, 2020 2 Born: Glasgow, Scotland, March 29, 1915 Died: Milton Keynes, England, Dec. 8, 1997 Introduction: We played again and again the marvellous Benny Carter session from Holland in 1937 with Coleman Hawkins. Then we realized that there was a great trombone player in there of British origin! Glad now to realize we had identified perhaps the best vintage trombone player on this side of the Atlantic! History: He took up trombone as a teenager after hearing Jack Teagarden. In 1936 he went to London with Teddy Joyce and played in clubs, notably the Nest Club, where the following year he took part in a jam session with Fats Waller, Coleman Hawkins and Benny Carter. Carter took him to Holland with a band that recorded eight titles for Decca (1937), and he played and recorded with Bert Ambrose’s orchestra in 1937-39. Chisholm was much in demand for session work; among his recordings was one with Waller for HMV in 1938. After joining the RAF he played in the all-star dance orchestra best known as the Squadronaires (1939-50). He was a member of the BBC Radio Show Band (1950-55) and played in Wally Stott’s orchestra in the “Goon Show” radio series, then performed with Jack Parnell and in musical shows until 1965. He continued to play jazz into the 1980s, both as a soloist – notably with Keith Smith’s Hefty Jazz – and with his own band, the Gentlemen of Jazz, in pubs, clubs and festivals. -

Extract from Chapter Four: When You Grow Up, Little Lady

Extract From Chapter Four: When You Grow Up, Little Lady In the summer of 1934, Lew took the band on the road again, and they played to sell-out audiences in Manchester, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Portsmouth and Nottingham, where Tiny Winters recalled that „people were scrambling for autographs in the interval, it was a near-riot. It really did bring home to us how people felt about the band.‟ When Al Bowlly sang, the dancers stopped dancing, and clustered ten-deep in front of the band-stand. In Bradford, he left the stage during an instrumental number, and was besieged by girls. He couldn‟t fight his way back to the microphone in time for his next vocal, and the band had to fill in for 32 bars. In that same year, Bowlly went to the USA, with Bill Harty, to sing with a new Ray Noble band. Alan Kane became the band‟s regular vocalist, while Jock Jacobson took over the drummer‟s stool. Albert Harris joined as guitarist, and Stanley Black was now on piano. In February 1935 the new band opened at the Hollywood Restaurant in Piccadilly. In March, trumpeter Nat Gonella left, to launch his career as a band-leader, with a smaller jazzier ensemble - The Georgians. Tommy McQuater took his place. At the Holborn Empire, Lew Stone made his debut as a comedian, with a languidly elegant rendering of the comedy song „Algernon Whifflesnoop John‟, complete with monocle, and supported by trumpeter Alfie Noakes as his obsequious butler. His deadpan vocal delivery also enhanced „The Gentleman Obviously Doesn‟t Believe‟, „Knock Knock‟, and most memorably „I‟ll be-BBCing You‟. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1930S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1930s Page 42 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1930 A Little of What You Fancy Don’t Be Cruel Here Comes Emily Brown / (Does You Good) to a Vegetabuel Cheer Up and Smile Marie Lloyd Lesley Sarony Jack Payne A Mother’s Lament Don’t Dilly Dally on Here we are again!? Various the Way (My Old Man) Fred Wheeler Marie Lloyd After Your Kiss / I’d Like Hey Diddle Diddle to Find the Guy That Don’t Have Any More, Harry Champion Wrote the Stein Song Missus Moore I am Yours Jack Payne Lily Morris Bert Lown Orchestra Alexander’s Ragtime Band Down at the Old I Lift Up My Finger Irving Berlin Bull and Bush Lesley Sarony Florrie Ford Amy / Oh! What a Silly I’m In The Market For You Place to Kiss a Girl Everybody knows me Van Phillips Jack Hylton in my old brown hat Harry Champion I’m Learning a Lot From Another Little Drink You / Singing a Song George Robey Exactly Like You / to the Stars Blue Is the Night Any Old Iron Roy Fox Jack Payne Harry Champion I’m Twenty-one today Fancy You Falling for Me / Jack Pleasants Beside the Seaside, Body and Soul Beside the Sea Jack Hylton I’m William the Conqueror Mark Sheridan Harry Champion Forty-Seven Ginger- Beware of Love / Headed Sailors If You were the Only Give Me Back My Heart Lesley Sarony Girl in the World Jack Payne George Robey Georgia On My Mind Body & Soul Hoagy Carmichael It’s a Long Way Paul Whiteman to Tipperary Get Happy Florrie Ford Boiled Beef and Carrots Nat Shilkret Harry Champion Jack o’ Lanterns / Great Day / Without a Song Wind in the Willows Broadway Baby Dolls -

Trevor Tolley Jazz Recording Collection

TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to collection ii Note on organization of 78rpm records iii Listing of recordings Tolley Collection 10 inch 78 rpm records 1 Tolley Collection 10 inch 33 rpm records 43 Tolley Collection 12 inch 78 rpm records 50 Tolley Collection 12 inch 33rpm LP records 54 Tolley Collection 7 inch 45 and 33rpm records 107 Tolley Collection 16 inch Radio Transcriptions 118 Tolley Collection Jazz CDs 119 Tolley Collection Test Pressings 139 Tolley Collection Non-Jazz LPs 142 TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION Trevor Tolley was a former Carleton professor of English and Dean of the Faculty of Arts from 1969 to 1974. He was also a serious jazz enthusiast and collector. Tolley has graciously bequeathed his entire collection of jazz records to Carleton University for faculty and students to appreciate and enjoy. The recordings represent 75 years of collecting, spanning the earliest jazz recordings to albums released in the 1970s. Born in Birmingham, England in 1927, his love for jazz began at the age of fourteen and from the age of seventeen he was publishing in many leading periodicals on the subject, such as Discography, Pickup, Jazz Monthly, The IAJRC Journal and Canada’s popular jazz magazine Coda. As well as having written various books on British poetry, he has also written two books on jazz: Discographical Essays (2009) and Codas: To a Life with Jazz (2013). Tolley was also president of the Montreal Vintage Music Society which also included Jacques Emond, whose vinyl collection is also housed in the Audio-Visual Resource Centre. -

Sep/Oct 2016 Volume 20, Issue 4

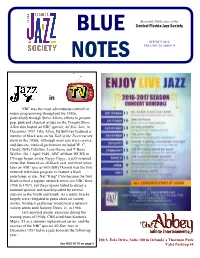

Bimonthly Publication of the Central Florida Jazz Society BLUE SEP/OCT 2016 VOLUME 20, ISSUE 4 NOTES in NBC was the most adventurous network in music programming throughout the 1950s, particularly through Steve Allen's efforts to present pop, jazz and classical artists on the Tonight Show. Allen also hosted an NBC special, All Star Jazz, in December 1957. Like Allen, Ed Sullivan featured a number of black acts on his Talk of the Town variety show in the 1950s. Although most acts were comics and dancers, musical performers included W. C. Handy, Billy Eckstine, Lena Horne and T-Bone Walker. On 1 April 1949, ABC affiliate WENR in Chicago began airing Happy Pappy, a jazz-oriented revue that featured an all-black cast, and three years later an ABC special with Billy Daniels was the first network television program to feature a black entertainer as star. Nat "King" Cole became the first black to host a regular network series (on NBC from 1956 to 1957), yet the program failed to attract a national sponsor and was boycotted by several stations in the North and South. As a result, blacks largely were relegated to guest shots on variety shows. No black performer would host a network variety series until Sammy Davis, Jr. in 1966. Jazz enjoyed greater exposure during the waning years of 1950s. CBS aired Stan Kenton's Music '55 as a summer replacement series, and the success of the NBC special All-Star Jazz in December 1957 led to a jazz boomlet the following year. 100 S. Eola Drive, Suite 100 in Orlando’s Thornton Park See JAZZ IN TV on page 5 Valet Parking $5 CFJS 3208 W. -

War: How Britain, Germany and the USA Used Jazz As Propaganda in World War II

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Studdert, Will (2014) Music Goes to War: How Britain, Germany and the USA used Jazz as Propaganda in World War II. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent. DOI Link to record in KAR http://kar.kent.ac.uk/44008/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Music Goes to War How Britain, Germany and the USA used Jazz as Propaganda in World War II Will Studdert Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Kent 2014 Word count (including footnotes): 96,707 255 pages Abstract The thesis will demonstrate that the various uses of jazz music as propaganda in World War II were determined by an evolving relationship between Axis and Allied policies and projects. -

Blues in the Blood a M U E S L B M L E O O R D

March 2011 | No. 107 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com J blues in the blood a m u e s l b m l e o o r d Johnny Mandel • Elliott Sharp • CAP Records • Event Calendar In his play Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare wrote, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” It is a lovely sentiment but one with which we agree only partially. So with that introduction, we are pleased to announce that as of this issue, the gazette formerly known as AllAboutJazz-New York will now be called The New York City Jazz Record. It is a change that comes on the heels of our separation New York@Night last summer from the AllAboutJazz.com website. To emphasize that split, we felt 4 it was time to come out, as it were, with our own unique identity. So in that sense, a name is very important. But, echoing Shakespeare’s idea, the change in name Interview: Johnny Mandel will have no impact whatsoever on our continuing mission to explore new worlds 6 by Marcia Hillman and new civilizations...oh wait, wrong mission...to support the New York City and international jazz communities. If anything, the new name will afford us new Artist Feature: Elliott Sharp opportunities to accomplish that goal, whether it be in print or in a soon-to-be- 7 by Martin Longley expanded online presence. We are very excited for our next chapter and appreciate your continued interest and support. On The Cover: James Blood Ulmer But back to the business of jazz. -

NJA British Jazz Timeline with Pics(Rev3) 11.06.19

British Jazz Timeline Pre-1900 – In the beginning The music to become known as ‘jazz’ is generally thought to have been conceived in America during the second half of the nineteenth century by African-Americans who combined their work songs, melodies, spirituals and rhythms with European music and instruments – a process that accelerated after the abolition of slavery in 1865. Black entertainment was already a reality, however, before this evolution had taken place and in 1873 the Fisk Jubilee Singers, an Afro- American a cappella ensemble, came to the UK on a fundraising tour during which they were asked to sing for Queen Victoria. The Fisk Singers were followed into Britain by a wide variety of Afro-American presentations such as minstrel shows and full-scale revues, a pattern that continued into the early twentieth century. [The Fisk Jubilee Singers c1890s © Fisk University] 1900s – The ragtime era Ragtime, a new style of syncopated popular music, was published as sheet music from the late 1890s for dance and theatre orchestras in the USA, and the availability of printed music for the piano (as well as player-piano rolls) encouraged American – and later British – enthusiasts to explore the style for themselves. Early rags like Charles Johnson’s ‘Dill Pickles’ and George Botsford’s ‘Black and White Rag’ were widely performed by parlour-pianists. Ragtime became a principal musical force in American and British popular culture (notably after the publication of Irving Berlin’s popular song ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’ in 1911 and the show Hullo, Ragtime! staged at the London Hippodrome the following year) and it was a central influence on the development of jazz. -

11 NEW MEMBERS a Total of Nine New Members Have Joined the Group Since the Issue of the Last Journal. No. 247 Ron Ellis Selby, N

Roots and Branches, series 1, issue 32 (Aug 2006) The official journal of the Plant Family History Group NEW MEMBERS A total of nine new members have joined the Group since the issue of the last Journal. No. 247 Ron Ellis Selby, North Yorkshire Ron learnt of the Plant Family History Group through the Guild of One Name Studies (GOONS) website, his connection with the Plant family being through his wife’s 5th G.Grandfather, Thomas Plant bn., c1714, living in Eyke, Suffolk in 1739 when John King was born to Martha King and Thomas Plant and christened in Eyke 23 September 1739. The next step is to find the birth/baptism of Thomas Plant c1714. There is no record in the IGI and it will probably be necessary to check the P.R., starting initially with Eyke followed by adjoining parishes. No. 248 Mrs KS Cosgrove Lach Dennis, Cheshire Mrs Cosgrove’s forebears on her father’s side originally came from Walsall, Wood, Staffordshire with a possible Wolverhampton connection. Her grandfather, Thomas Plant, moved to New Brighton, Cheshire, where some of his children remained, although some were also living in Staffordshire. Thomas Plant born c1888, was the son of Thomas/James Plant and Ann Wells. He married Ann Addis, 23 December 1908 and their eldest son, also named Thomas was born 14 November 1910 in Wallasey, Cheshire. There was a total of eight children, Thomas, Emily, Benjamin, Irene, Francis, Rhoda, Edith and Eric. The only other known information is that Thomas Plant (born c1888) had at least three siblings, James, George and Annie. -

Start Time Description Number-Cut Length User Defined 00:00:00 TOP

Start Time Description Number-Cut Length User defined 00:00:00 TOP OF HOUR 00:00:00 RUN MACRO-ON AIR 00:00:00-E (:00)LEGAL ID 00:00:00-E (:00)Enjoy Yourself (It's Later Than You Thin 0069603-001 03:17:0 Artist - Guy Lombardo 00:03:17-E (:00)Funny Face 0027019-001 03:04:0 Artist - Fred Astaire and Adele Astaire 00:06:21-E (:00)HERE'S THAT RAINY DAY 0032601-001 03:55:0 Artist - JOE BURKE 00:10:16-E (:00)Billy the Kid 0038503-001 02:18:0 Artist - Marty Robbins 00:12:34-E (:00)A LITTLE CONSIDERATION 0039014-001 02:49:0 Artist - FRANKIE CARLE AND HIS ORCHESTRA v MARJORIE HUGHES 00:15:23-E (:00)Vaya Con Dios 0041309-001 02:40:0 Artist - Anacani 00:18:04-E (:00)BATS IN THE BELFRY 0014204-001 03:07:3 Artist - BILLY MAYERL 00:21:11-E (:00)ON THE AVENUE 0013913-001 02:42:6 Artist - THE THREE SUNS 00:23:54-E (:00)IF YOU BUILD A BETTER MOUSETRAP 0007113-001 02:28:0 Artist - HAL MCINTYRE AND HIS ORCH v PENNY PARKER-JACK LATHROP 00:26:22-E (:00)G. T. Stomp 0044011-001 02:38:0 Artist - Earl Hines 00:29:00-E (:00)Maybe - Who Knows 0047318-001 03:05:0 Artist - TED LEWIS 00:32:05-E (:00)LIFE IS A SONG (LET'S SING IT TOGETHER) 0052308-001 02:12:0 Artist - BILL CHALLIS AND HIS ORCHESTRA 00:34:17-E (:00)I Know That You Know 0054802-001 01:11:0 Artist - Buddy Clark 00:35:28-E (:00)Somebody Stole My Gal 0054606-001 03:01:0 Artist - Benny Goodman 00:38:29-E (:00)JUG BAND MUSIC 0054208-001 04:28:0 Artist - PAUL MOORE'S AMAZING WASHBOARD WIZARDSER-JACK LATHROP 00:42:57-E (:00)I Still Remember 0062905-001 02:56:0 Artist - Rudy Valle and His Connecticut YankeesER-JACK -

Johnny Green's Body and Soul. from New York to London and Back

Johnny Green’s Body and Soul. From New York to London and Back. Albert Haim John Simpson’s Blog, August 13, 2011 It starts in silence. By the end, the singer has thrown him- or herself melodramatically, almost operatically on the mercy of a lost love. It’s drenched in self-pity, but was written for and first performed by a woman once dubbed “Hollywood’s first maneater.” One of its most famous covers includes no vocal at all, and barely follows the tune. And it’s gone on to become, arguably, the single most-recorded pop standard in history. Introduction. Body and Soul, a 1929 composition by Johnny Green (music), Edward Heyman, Robert Sour and Frank Eyton (lyrics) is the most recorded song of all times. Tom Lord’s jazz discography lists over 2000 recordings and broadcast performances of the song and there probably are nearly 3000. Body and Soul is both a jazz standard and a popular song. In view of the importance of the tune in the realms of jazz and popular music, it is surprising that the literature (both print and internet) provides incorrect information about the genesis of the song –where, when and for whom it was composed and what are the dates of the first recordings. It has been reported that Body and Soul was sung by Gertrude Lawrence in England in the summer of 1929. The song spread like wildfire (in the very words of Johnny Green himself, see below) and by the end of 1930, there were seventeen recordings of the song in England.