The Evolving Presence of Jazz in Britain Chapter 4 Case Study: in Dahomey: a Negro Musical Comedy in London, 1903

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

SOMERSET FOLK All Who Roam, Both Young and Old, DECEMBER TOP SONGS CLASSICAL Come Listen to My Story Bold

Folk Singing Broadsht.2 5/4/09 8:47 am Page 1 SOMERSET FOLK All who roam, both young and old, DECEMBER TOP SONGS CLASSICAL Come listen to my story bold. 400 OF ENGLISH COLLECTED BY For miles around, from far and near, YEARS FOLK MUSIC TEN FOLK They come to see the rigs o’ the fair, 11 Wassailing SOMERSET CECIL SHARP 1557 Stationers’ Company begins to keep register of ballads O Master John, do you beware! Christmastime, Drayton printed in London. The Seeds of Love Folk music has inspired many composers, and And don’t go kissing the girls at Bridgwater Fair Mar y Tudor queen. Loss of English colony at Calais The Outlandish Knight in England tunes from Somerset singers feature The lads and lasses they come through Tradtional wassailing 1624 ‘John Barleycorn’ first registered. John Barleycorn in the following compositions, evoking the very From Stowey, Stogursey and Cannington too. essence of England’s rural landscape: can also be a Civil Wars 1642-1650, Execution of Charles I Barbara Allen SONG COLLECTED BY CECIL SHARP FROM visiting 1660s-70s Samuel Pepys makes a private ballad collection. Percy Grainger’s passacaglia Green Bushes WILLIAM BAILEY OF CANNINGTON AUGUST 8TH 1906 Lord Randal custom, Restoration places Charles II on throne was composed in 1905-6 but not performed similar to carol The Wraggle Taggle Gypsies 1765 Reliques of Ancient English Poetry published by FOLK 5 until years later. It takes its themes from the 4 singing, with a Thomas Percy. First printed ballad collection. Dabbling in the Dew ‘Green Bushes’ tune collected from Louie bowl filled with Customs, traditions & glorious folk song Mozart in London As I walked Through the Meadows Hooper of Hambridge, plus a version of ‘The cider or ale. -

The History of Women in Jazz in Britain

The history of jazz in Britain has been scrutinised in notable publications including Parsonage (2005) The Evolution of Jazz in Britain, 1880-1935 , McKay (2005) Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain , Simons (2006) Black British Swing and Moore (forthcoming 2007) Inside British Jazz . This body of literature provides a useful basis for specific consideration of the role of women in British jazz. This area is almost completely unresearched but notable exceptions to this trend include Jen Wilson’s work (in her dissertation entitled Syncopated Ladies: British Jazzwomen 1880-1995 and their Influence on Popular Culture ) and George McKay’s chapter ‘From “Male Music” to Feminist Improvising’ in Circular Breathing . Therefore, this chapter will provide a necessarily selective overview of British women in jazz, and offer some limited exploration of the critical issues raised. It is hoped that this will provide a stimulus for more detailed research in the future. Any consideration of this topic must necessarily foreground Ivy Benson 1, who played a fundamental role in encouraging and inspiring female jazz musicians in Britain through her various ‘all-girl’ bands. Benson was born in Yorkshire in 1913 and learned the piano from the age of five. She was something of a child prodigy, performing on Children’s Hour for the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) at the age of nine. She also appeared under the name of ‘Baby Benson’ at Working Men’s Clubs (private social clubs founded in the nineteenth century in industrial areas of Great Britain, particularly in the North, with the aim of providing recreation and education for working class men and their families). -

Music Outside? the Making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde 1968-1973

Banks, M. and Toynbee, J. (2014) Race, consecration and the music outside? The making of the British jazz avant-garde 1968-1973. In: Toynbee, J., Tackley, C. and Doffman, M. (eds.) Black British Jazz. Ashgate: Farnham, pp. 91-110. ISBN 9781472417565 There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/222646/ Deposited on 28 August 2020 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Race, Consecration and the ‘Music Outside’? The making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde: 1968-1973 Introduction: Making British Jazz ... and Race In 1968 the Arts Council of Great Britain (ACGB), the quasi-governmental agency responsible for providing public support for the arts, formed its first ‘Jazz Sub-Committee’. Its main business was to allocate bursaries usually consisting of no more than a few hundred pounds to jazz composers and musicians. The principal stipulation was that awards be used to develop creative activity that might not otherwise attract commercial support. Bassist, composer and bandleader Graham Collier was the first recipient – he received £500 to support his work on what became the Workpoints composition. In the early years of the scheme, further beneficiaries included Ian Carr, Mike Gibbs, Tony Oxley, Keith Tippett, Mike Taylor, Evan Parker and Mike Westbrook – all prominent members of what was seen as a new, emergent and distinctively British avant-garde jazz scene. Our point of departure in this chapter is that what might otherwise be regarded as a bureaucratic footnote in the annals of the ACGB was actually a crucial moment in the history of British jazz. -

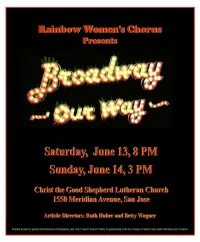

Broadway-Our-Way-2015.Pdf

Our Mission Rainbow Women’s Chorus works together to develop musical excellence in an atmosphere of mutual support and respect. We perform publicly for the entertainment, education and cultural enrichment of our audiences and community. We sing to enhance the esteem of all women, to celebrate diversity, to promote peace and freedom, and to touch people’s hearts and lives. Our Story Rainbow Women’s Chorus is a nonprofit corporation governed by the Action Circle, a group of women dedicated to realizing the organization’s mission. Chorus members began singing together in 1996, presenting concerts in venues such as Christ the Good Shepherd Lutheran Church, Le Petit Trianon Theatre, the San Jose Repertory Theater and Triton Museum. The chorus also performs at church services, diversity celebrations, awards ceremonies, community meetings and private events. Rainbow Women’s Chorus is a member of the Gay and Lesbian Association of Choruses (GALA). In 2000, RWC proudly co-hosted GALA Festival in San Jose, with the Silicon Valley Gay Men’s Chorus. Since then, RWC has participated in GALA Festivals in Montreal (2004), Miami (2008), and Denver (2012). In February 2006, members of RWC sang at Carnegie Hall in NYC with a dozen other choruses for a breast cancer and HIV benefit. In July 2010, RWC traveled to Chicago for the Sister Singers Women’s Choral Festival. But we like it best when we are here at home, singing for you! Support the Arts Rainbow Women’s Chorus and other arts organizations receive much valued support from Silicon Valley Creates, not only in grants, but also in training, guidance, marketing, fundraising, and more. -

{Download PDF} Cultural Traditions in the United Kingdom

CULTURAL TRADITIONS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lynn Peppas | 32 pages | 24 Jul 2014 | Crabtree Publishing Co,Canada | 9780778703136 | English | New York, Canada Cultural Traditions in the United Kingdom PDF Book Retrieved 11 July It was designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott in and was launched by the post office as the K2 two years after. Under the Labour governments of the s and s most secondary modern and grammar schools were combined to become comprehensive schools. Due to the rise in the ownership of mobile phones among the population, the usage of the red telephone box has greatly declined over the past years. In , scouting in the UK experienced its biggest growth since , taking total membership to almost , We in Hollywood owe much to him. Pantomime often referred to as "panto" is a British musical comedy stage production, designed for family entertainment. From being a salad stop to housing a library of books, ingenious ways are sprouting up to save this icon from total extinction. The Tate galleries house the national collections of British and international modern art; they also host the famously controversial Turner Prize. Jenkins, Richard, ed. Non-European immigration in Britain has not moved toward a pattern of sharply-defined urban ethnic ghettoes. Media Radio Television Cinema. It is a small part of the tartan and is worn around the waist. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. At modern times the British music is one of the most developed and most influential in the world. Wolverhampton: Borderline Publications. Initially idealistic and patriotic in tone, as the war progressed the tone of the movement became increasingly sombre and pacifistic. -

Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises a Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920S-1950S)

Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises A Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s-1950s) Veronica Chincoli Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 15 April 2019 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises A Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s- 1950s) Veronica Chincoli Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Professor Stéphane Van Damme, European University Institute Professor Laura Downs, European University Institute Professor Catherine Tackley, University of Liverpool Professor Pap Ndiaye, SciencesPo © Veronica Chincoli, 2019 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Researcher declaration to accompany the submission of written work Department of History and Civilization - Doctoral Programme I Veronica Chincoli certify that I am the author of the work “Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises: A Transnatioanl Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s-1950s). I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. at the European University Institute. I also certify that this is solely my own original work, other than where I have clearly indicated, in this declaration and in the thesis, that it is the work of others. I warrant that I have obtained all the permissions required for using any material from other copyrighted publications. I certify that this work complies with the Code of Ethics in Academic Research issued by the European University Institute (IUE 332/2/10 (CA 297). -

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business. -

New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation

New Orleans' Welcome to Jazz country, where Maison Blanche our heartbeat is a down beat and salutes the the sounds of music fill the air . Welcome to Maison Blanche coun• New Orleans Jazz try, where you are the one who calls the tune and fashion is our and Heritage daily fare. Festival 70 maison blanche NEW ORLEANS Schedule WEDNESDAY - APRIL 22 8 p.m. Mississippi River Jazz Cruise on the Steamer President. Pete Fountain and his Orchestra; Clyde Kerr and his Orchestra THURSDAY - APRIL 23 12:00 Noon Eureka Brass Band 12:20 p.m. New Orleans Potpourri—Harry Souchon, M.C. Armand Hug, Raymond Burke, Sherwood Mangiapane, George Finola, Dick Johnson Last Straws 3:00 p.m. The Musical World of French Louisiana- Dick Allen and Revon Reed, M. C.'s Adam Landreneau, Cyprien Landreneau, Savy Augustine, Sady Courville, Jerry Deville, Bois Sec and sons, Ambrose Thibodaux. Clifton Chenier's Band The Creole Jazz Band with Dede Pierce, Homer Eugene, Cie Frazier, Albert Walters, Eddie Dawson, Cornbread Thomas. Creole Fiesta Association singers and dancers. At the same time outside in Beauregard Square—for the same $3 admission price— you'll have the opportunity to explore a variety of muical experiences, folklore exhibits, the art of New Orleans and the great food of South Louisiana. There will be four stages of music: Blues, Cajun, Gospel and Street. The following artists will appear throughout the Festival at various times on the stages: Blues Stage—Fird "Snooks" Eaglin, Clancy "Blues Boy" Lewis, Percy Randolph, Smilin Joe, Roosevelt Sykes, Willie B. Thomas, and others. -

• Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit Amet • Consectetur Adipisicing Elit • Sed

Beeld en Geluid • Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet • Consectetur adipisicing elit • Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore • Et dolore magna aliqua Hooked on Music John Ashley Burgoyne Music Cognition Group Institute for Logic, Language and Computation University of Amsterdam Hooked on Music John Ashley Burgoyne · Jan Van Balen Dimitrios Bountouridis · Daniel Müllensiefen Frans Wiering · Remco C. Veltkamp · Henkjan Honing and thanks to Fleur Bouwer · Maarten Brinkerink · Aline Honingh · Berit Janssen · Richard Jong !emistoklis Karavellas · Vincent Koops · Laura Koppenburg · Leendert van Maanen Han van der Maas · Tobin May · Jaap Murre · Marieke Navin · Erinma Ochu Johan Oomen · Carlos Vaquero · Bastiaan van der Weij ‘Henry’ Dan Cohen & Michael Rossato-Benne" · 2014 · Alive Inside Long-term Musical Salience salience · the absolute ‘noticeability’ of something • cf. distinctiveness (relative salience) musical · what makes a bit of music stand out long-term · what makes a bit of music stand out so much that it remains stored in long-term memory Cascading Reminiscence Bumps 2063 a Listeners Listeners Born Age 20 Years 10 9 8 7 6 Personal Memories 5 Quality Rating 4 3 2 1 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 5-Year Period Parents Parents ReminiscenceBorn Age 20 Years Bumps b Listeners Listeners Born Age 20 Years 10 9 8 Personal Memories 7 6 Recognize 5 Like Rating 4 3 2 1 • critical period ages 15–25 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 5-Year Period • multi-generational Parents Parents Born Age 20 Years • parents and grandparents Fig. 2. Mean rating of the extent to which participants had personal memories associated with the songs of each 5-year period, together with (a) the judged quality of the songs and (b) whether participants liked and recognized the songs (after the percentage recognized was converted to the number of songs recognized). -

Fascinating Rhythm”—Fred and Adele Astaire; George Gershwin, Piano (1926) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Kathleen Riley (Guest Post)*

“Fascinating Rhythm”—Fred and Adele Astaire; George Gershwin, piano (1926) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Kathleen Riley (guest post)* George Gerswhin Fred Astaire Adele Astaire In 1927 George Gershwin told an interviewer that, in order to achieve truth or authenticity, music “must repeat the thoughts and aspirations of the people and the time.” “My people are Americans,” he said, “My time is today.” In London the previous year, Gershwin and the stars of “Lady, Be Good!,” Fred and Adele Astaire, made a recording of “Fascinating Rhythm,” a song that seemed boldly to proclaim its modernity and its Americanness. Nearly a century after its composition we can still hear the very things playwright S.N. Behrman experienced the moment Gershwin sat down at a party to play the piano: “the newness, the humor, above all the rush of the great heady surf of vitality.” What is also discernible in the 1926 recording--in Gershwin’s opening flourish on the piano and in the 16-bar verse sung by the Astaires--is the gathering momentum of a steam locomotive, a hypnotic, hurtling movement into the future. Born in 1898 and 1899 respectively, George Gershwin and Fred Astaire were manifestly children of the Machine Age. Astaire was born deep in the Midwest, in Omaha, Nebraska, where his earliest memory was “the rumbling of the locomotives in the distance as engines switched freight cars in the evening when we sat on the front porch and also after I went to bed. That and the railway whistles in the night, going someplace.