An Online Open Access Journal ISSN 0975-2935

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TUESDAYS with MORRIE by Jeffrey Hatcher & Mitch Albom Adapted from the Book by Mitch Albom

streaming February 2 – 21, 2021 from the OneAmerica Mainstage filmed by WFYI STUDY GUIDE edited by Richard J Roberts, Resident Dramaturg with contributions by Janet Allen • Benjamin Hanna Rob Koharchik • Guy Clark • Melanie Chen Cole Indiana Repertory Theatre 140 West Washington Street Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 Janet Allen, Margot Lacy Eccles Artistic Director Suzanne Sweeney, Managing Director www. irtlive.com SEASON SEASON EDUCATION SPONSOR PARTNER PARTNER ASSOCIATE SPONSORS SEASON SUPPORT 2 TUESDAYS WITH MORRIE by Jeffrey Hatcher & Mitch Albom adapted from the book by Mitch Albom Morrie was Mitch’s sociology professor, but he was also his mentor, his advisor, his life coach. Now Mitch is a busy sportswriter with a frantic schedule and a troubled marriage, and Morrie is dying. One visit turns into a weekly pilgrimage and a final course in the meaning of life. The beloved book comes to life in this life-affirming play, full of compassion, humor, and hope. STREAMING February 2 – 21, 2021 LENGTH Approximately 1 hour, 30 minutes AGE RANGE Recommended for grades 9–12 STUDY GUIDE CONTENTS About the Play 3 Artistic Director’s Note 4 From the Director 6 Interview with the Playwright 7 Designer Notes 8 ALS 10 Standards Alignment Guide 11 Discussion Questions 12 Writing Prompts 13 Activities 14 Resources 19 Glossary 21 FOR INFORMATION ABOUT IRT’S EDUCATION PROGRAMS: [email protected] COVER ART BY KYLE RAGSDALE FOR STREAMING SALES: IRT Ticket Office: 317-635-5252 www.irtlive.com 3 THE STORY OF TUESDAYS WITH MORRIE Morrie Schwartz taught sociology at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, beginning in 1959. -

Brothers Under Fire Canadian Fire Fighters

The 1940s Society For Everyone Interested in Wartime Britain Issue 72 March / April 2012 £3.00 Blitz Kids Sean Longden on the Childrens war against Hitler Brothers Under Fire Canadian Fire Fighters. 2 part article by John Leete Lew Stone Jeff “Two-Tone Boogie” discovers more about this influential musician Diary Events and much more.... The 1940’s Society, 90 Lennard Road, Dunton Green, Sevenoaks, Kent TN13 2UX Tel: 01732 452505 Web: www.1940.co.uk Email: [email protected] 1 Enjoy Life The 1940s Society I don’t really follow football but I’m writing this after hearing that For Everyone Interested in Wartime Britain Fabrice Muamba remains in a critical condition in intensive care after suffering a cardiac arrest during the FA Cup tie at Tottenham. Regular meetings at Otford Memorial Hall near Sevenoaks A shock to all as he is a young fit 23 year old with no previous signs of health issues. Like many people I remember him in my prayers Friday 30th March 2012 - 8pm and wish him a speedy recovery. You may think it’s a rather sombre start to the magazine but I like to Blitz Kids think of it as a reminder of how fragile our lives are. A reminder that Britain’s children in the Second World War both we should make the most of what we have, smile, and take the time at home and on the front line to enjoy our lives. I’ve been reading the proofs of a book being published in June (Parachute Doctor) and you suddenly realise how Sean Longden death was such an everyday occurrence during the Second World War. -

George Chisholm

1 The TROMBONE of GEORGE CHISHOLM Solographer: Jan Evensmo Last update: March 9, 2020 2 Born: Glasgow, Scotland, March 29, 1915 Died: Milton Keynes, England, Dec. 8, 1997 Introduction: We played again and again the marvellous Benny Carter session from Holland in 1937 with Coleman Hawkins. Then we realized that there was a great trombone player in there of British origin! Glad now to realize we had identified perhaps the best vintage trombone player on this side of the Atlantic! History: He took up trombone as a teenager after hearing Jack Teagarden. In 1936 he went to London with Teddy Joyce and played in clubs, notably the Nest Club, where the following year he took part in a jam session with Fats Waller, Coleman Hawkins and Benny Carter. Carter took him to Holland with a band that recorded eight titles for Decca (1937), and he played and recorded with Bert Ambrose’s orchestra in 1937-39. Chisholm was much in demand for session work; among his recordings was one with Waller for HMV in 1938. After joining the RAF he played in the all-star dance orchestra best known as the Squadronaires (1939-50). He was a member of the BBC Radio Show Band (1950-55) and played in Wally Stott’s orchestra in the “Goon Show” radio series, then performed with Jack Parnell and in musical shows until 1965. He continued to play jazz into the 1980s, both as a soloist – notably with Keith Smith’s Hefty Jazz – and with his own band, the Gentlemen of Jazz, in pubs, clubs and festivals. -

Extract from Chapter Four: When You Grow Up, Little Lady

Extract From Chapter Four: When You Grow Up, Little Lady In the summer of 1934, Lew took the band on the road again, and they played to sell-out audiences in Manchester, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Portsmouth and Nottingham, where Tiny Winters recalled that „people were scrambling for autographs in the interval, it was a near-riot. It really did bring home to us how people felt about the band.‟ When Al Bowlly sang, the dancers stopped dancing, and clustered ten-deep in front of the band-stand. In Bradford, he left the stage during an instrumental number, and was besieged by girls. He couldn‟t fight his way back to the microphone in time for his next vocal, and the band had to fill in for 32 bars. In that same year, Bowlly went to the USA, with Bill Harty, to sing with a new Ray Noble band. Alan Kane became the band‟s regular vocalist, while Jock Jacobson took over the drummer‟s stool. Albert Harris joined as guitarist, and Stanley Black was now on piano. In February 1935 the new band opened at the Hollywood Restaurant in Piccadilly. In March, trumpeter Nat Gonella left, to launch his career as a band-leader, with a smaller jazzier ensemble - The Georgians. Tommy McQuater took his place. At the Holborn Empire, Lew Stone made his debut as a comedian, with a languidly elegant rendering of the comedy song „Algernon Whifflesnoop John‟, complete with monocle, and supported by trumpeter Alfie Noakes as his obsequious butler. His deadpan vocal delivery also enhanced „The Gentleman Obviously Doesn‟t Believe‟, „Knock Knock‟, and most memorably „I‟ll be-BBCing You‟. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1930S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1930s Page 42 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1930 A Little of What You Fancy Don’t Be Cruel Here Comes Emily Brown / (Does You Good) to a Vegetabuel Cheer Up and Smile Marie Lloyd Lesley Sarony Jack Payne A Mother’s Lament Don’t Dilly Dally on Here we are again!? Various the Way (My Old Man) Fred Wheeler Marie Lloyd After Your Kiss / I’d Like Hey Diddle Diddle to Find the Guy That Don’t Have Any More, Harry Champion Wrote the Stein Song Missus Moore I am Yours Jack Payne Lily Morris Bert Lown Orchestra Alexander’s Ragtime Band Down at the Old I Lift Up My Finger Irving Berlin Bull and Bush Lesley Sarony Florrie Ford Amy / Oh! What a Silly I’m In The Market For You Place to Kiss a Girl Everybody knows me Van Phillips Jack Hylton in my old brown hat Harry Champion I’m Learning a Lot From Another Little Drink You / Singing a Song George Robey Exactly Like You / to the Stars Blue Is the Night Any Old Iron Roy Fox Jack Payne Harry Champion I’m Twenty-one today Fancy You Falling for Me / Jack Pleasants Beside the Seaside, Body and Soul Beside the Sea Jack Hylton I’m William the Conqueror Mark Sheridan Harry Champion Forty-Seven Ginger- Beware of Love / Headed Sailors If You were the Only Give Me Back My Heart Lesley Sarony Girl in the World Jack Payne George Robey Georgia On My Mind Body & Soul Hoagy Carmichael It’s a Long Way Paul Whiteman to Tipperary Get Happy Florrie Ford Boiled Beef and Carrots Nat Shilkret Harry Champion Jack o’ Lanterns / Great Day / Without a Song Wind in the Willows Broadway Baby Dolls -

War: How Britain, Germany and the USA Used Jazz As Propaganda in World War II

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Studdert, Will (2014) Music Goes to War: How Britain, Germany and the USA used Jazz as Propaganda in World War II. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent. DOI Link to record in KAR http://kar.kent.ac.uk/44008/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Music Goes to War How Britain, Germany and the USA used Jazz as Propaganda in World War II Will Studdert Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Kent 2014 Word count (including footnotes): 96,707 255 pages Abstract The thesis will demonstrate that the various uses of jazz music as propaganda in World War II were determined by an evolving relationship between Axis and Allied policies and projects. -

The Movies and Music of the 1930S the Depression Was a Tough Time for Families and Kids Since Money Was Scarce

The Movies and Music of the 1930s The depression was a tough time for families and kids since money was scarce. Even though this was the case and there were no television sets to watch, people managed by swimming in the canals, dancing at the Women’s Club for 25 cents, or going to the movies in Glendale. Here are the top movies that came out during the ’30s as well as the music that came out during this period. 1930 - Top Movies - Tom Sawyer, Top Hat, Animal Crackers, and Hell’s Angels Top Music “Happy Days Are Here Again” (Ben Selvin), “These Little Words” (Duke Ellington), “On the Sunny Side of the Street” (Ted Lewis and his Orchestra) 1931 – Top Movies – Frankenstein, City Lights, Mata Hari, Cimarron - Top Music - “Minnie the Moocher” (Cab Calloway), “Dream a Little Dream of Me” (Wayne King), “Goodnight Sweetheart” (Bing Crosby) 1932 - Top Movies – Tarzan the Ape Man, Trouble in Paradise, The Old Dark House. - Top Music – “All of Me” (Louis Armstrong), “It Don’t Mean a Thing” (Duke Ellington), “Night and Day” (Fred Astaire and Leo Raisman) 1933 - Top Movies – King Kong, 42ndStreet, Dinner at Eight, Sons of the Desert - Top Music – “Stormy Weather” (Ethel Waters), “Sophisticated Lady” (Duke Ellington) “We’re in the Money” (Dick Powell) 1934 - Top Movies – The Thin Man, Cleopatra, It Happened One Night - Top Music – “Moon Glow” (Benny Goodman), “Tumbling Tumbleweeds” (Paul Whitman), “Smoke Gets In Your Eyes” (Paul Whitman), “Cocktails for Two” (Duke Ellington) 1935 - Top Movies – Mutiny on the Bounty, Top Hat, Captain Blood, A Night At the Opera - Top Music – “On the Good Ship Lollipop” (Shirley Temple) “Cheek to Cheek” (Fred Astaire), “The Isle of Capri” (Ray Noble), “Lullaby of Broadway” (Blue Moon) 1936 - Top Movies – The Great Ziegfeld, Mr. -

Down-Beat-1940-02-01

DOWN BEAT Chicago. February 1, 194| Benny’s band. I pointed out that maybi there was another way to play sax in a section, and w I Doni Want a Jazz Band slowly worked «»ut the style w» use now. Sure it was tough, bu all the boyi- know what I want and they’re fast to learn.” He Claims Harmony, Hol a Beat, Result? Miller’s saxes are the most famous in the land today. For the record?, Miller wa- born From i Is What Counts With the Public March 1, 1905, in Clarinda Iowa. Circle of BY DAVE DEXTER, JR. But he didn’t stay in the con c juntry long. His parents moved to or stolen) New York—“I haven’t it great jazz band, and I don’t want Denver, ana ut there, in the uid take« qui of the Rockie- and “tall” air, pro,' ed. one. Glenn learned to play trombone. Glenn Miller isn’t one to waste words. And he doesn’t He was still a moppet when ho aervationa waste any describing the music his band is playing these started playing professionally. amount l nights at the Hotel Pennsylvania here. Soft-spoken, sincere Rose From Noble Band Instance 1 and earnest in his conversation, Miller is now finding him Glenn first became prominent, like com self at the top of the nation’s long list of favorite maestri. nationally, while with Ray Noble’» it docan'l If you’rt first American dance band fiv» “We leaders are criticized for a lot of things.” says Miller. -

11 NEW MEMBERS a Total of Nine New Members Have Joined the Group Since the Issue of the Last Journal. No. 247 Ron Ellis Selby, N

Roots and Branches, series 1, issue 32 (Aug 2006) The official journal of the Plant Family History Group NEW MEMBERS A total of nine new members have joined the Group since the issue of the last Journal. No. 247 Ron Ellis Selby, North Yorkshire Ron learnt of the Plant Family History Group through the Guild of One Name Studies (GOONS) website, his connection with the Plant family being through his wife’s 5th G.Grandfather, Thomas Plant bn., c1714, living in Eyke, Suffolk in 1739 when John King was born to Martha King and Thomas Plant and christened in Eyke 23 September 1739. The next step is to find the birth/baptism of Thomas Plant c1714. There is no record in the IGI and it will probably be necessary to check the P.R., starting initially with Eyke followed by adjoining parishes. No. 248 Mrs KS Cosgrove Lach Dennis, Cheshire Mrs Cosgrove’s forebears on her father’s side originally came from Walsall, Wood, Staffordshire with a possible Wolverhampton connection. Her grandfather, Thomas Plant, moved to New Brighton, Cheshire, where some of his children remained, although some were also living in Staffordshire. Thomas Plant born c1888, was the son of Thomas/James Plant and Ann Wells. He married Ann Addis, 23 December 1908 and their eldest son, also named Thomas was born 14 November 1910 in Wallasey, Cheshire. There was a total of eight children, Thomas, Emily, Benjamin, Irene, Francis, Rhoda, Edith and Eric. The only other known information is that Thomas Plant (born c1888) had at least three siblings, James, George and Annie. -

American Heritage Center

UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING AMERICAN HERITAGE CENTER GUIDE TO ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY RESOURCES Child actress Mary Jane Irving with Bessie Barriscale and Ben Alexander in the 1918 silent film Heart of Rachel. Mary Jane Irving papers, American Heritage Center. Compiled by D. Claudia Thompson and Shaun A. Hayes 2009 PREFACE When the University of Wyoming began collecting the papers of national entertainment figures in the 1970s, it was one of only a handful of repositories actively engaged in the field. Business and industry, science, family history, even print literature were all recognized as legitimate fields of study while prejudice remained against mere entertainment as a source of scholarship. There are two arguments to be made against this narrow vision. In the first place, entertainment is very much an industry. It employs thousands. It requires vast capital expenditure, and it lives or dies on profit. In the second place, popular culture is more universal than any other field. Each individual’s experience is unique, but one common thread running throughout humanity is the desire to be taken out of ourselves, to share with our neighbors some story of humor or adventure. This is the basis for entertainment. The Entertainment Industry collections at the American Heritage Center focus on the twentieth century. During the twentieth century, entertainment in the United States changed radically due to advances in communications technology. The development of radio made it possible for the first time for people on both coasts to listen to a performance simultaneously. The delivery of entertainment thus became immensely cheaper and, at the same time, the fame of individual performers grew. -

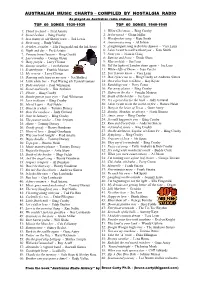

Australian Music Charts – Compiled by Nostalgia Radio

AUSTRALIAN MUSIC CHARTS – COMPILED BY NOSTALGIA RADIO As played on Australian radio stations TOP 60 SONGS 1930-1939 TOP 60 SONGS 1940-1949 1: Cheek to cheek - Fred Astaire 1: White Christmas - Bing Crosby 2: Sweet Leilani - Bing Crosby 2: In the mood - Glenn Miller 3: In a shanty in old Shanty town - Ted Lewis 3: Woodpecker song - Kate Smith 4: Stein song - Rudy Vallee 4: Anniversary song - Al Jolson 5: A-tisket, a-tasket - Ella Fitzgerald and the Ink Spots 5: A nightingale sang in Berkley Square - Vera Lynn 6: Night and day - Fred Astaire 6: I don’t want to walk without you - Kate Smith 7: Pennies from Heaven - Bing Crosby 7: Near you - Francis Craig 8: Last roundup - George Olsen 8: Buttons and Bows - Dinah Shore 9: Deep purple - Larry Clinton 9: Blue orchids - Joe Loss 10: Stormy weather - Leo Reisman 10: Till the lights of London shine again - Joe Loss 11: Scatterbrain - Frankie Masters 11: White cliffs of Dover - Jean Cerchi 12: My reverie - Larry Clinton 12: You’ll never know - Vera Lynn 13: Dancing with tears in my eyes - Nat Shilkret 13: Don’t fence me in - Bing Crosby a/t Andrews Sisters 14: Little white lies - Fred Waring a/h Pennsylvanians 14: On a slow Boat to China - Kay Kyser 15: Body and soul - Paul Whiteman 15: RamBling rose - Perry Como 16: Sweet and lovely - Gus Arnheim 16: Far away places - Bing Crosby 17: Please - Bing Crosby 17: Riders in the sky - Vaughn Monroe 18: Smoke gets in your eyes - Paul Whiteman 18: South of the border - Joe Loss 19: Love in bloom - Bing Crosby 19: It’s a great day for the Irish - Judy Garland -

Model Musician Sounds Provided By: Jim Matthews Who Are YOUR

Model Musician Sounds Provided by: Jim Matthews Who are YOUR models for music? Which performing artists do YOU listen to? Who do you play for your students as a STANDARD - model of excellence? This certainly is NOT a complete list as there are many models which are not listed. This is simply a start. Flute - Emmanuel Pahud, Andreas Blau, Sharon Bezaly, Julius Baker, Jean-Pierre Rampal, James Galway, Ian Clarke, Thomas Robertello, Mimi Stillman, Aurele Nicolet, Jasmine Choi, Paula Robison, Andrea Griminelli, Jane Rutter, Jeanne Baxtresser, Sefika Kutluer, Jazz: Hubert Laws, Nestor Torres, Greg Patillo (beatbox), Ian Anderson (Jethro Tull), Herbie Mann, Dave Valentine, Oboe - Albrecht Mayer, Marcel Tabuteau, John Mack, Joe Robinson, Alex Klein, Eugene Izotov, Heinz Holliger, Elaine Douvas, John de Lancie, Andreas Whitteman, Richard Woodhams, Ralph Gomberg, Katherine Needleman, Marc Lifschey, David Weiss, Liang Wang, Francios Leleux, Bassoon - David McGill, Arthur Grossman, Klaus Thunemann, Dag Jensen, Joseph Polisi, Frank Morrelli, Judith LeClair, Breaking Winds Bassoon Quartet, Albrecht Holder, Milan Turkovic, Gustavo Nunez, Antoine Bullant, Bill Douglas, Julie Price, Asger Svendsen, Carl Almenrader, Karen Geoghegan, Clarinet - Sabine Meyer, Julian Bliss, Andrew Mariner, Martin Frost, Larry Combs, Stanley Drucker, Alessandro Carbonare, John Manasse, Sharon Kam, Karl Leister, Ricardo Morales, Jack Brymer, Yehuda Gilad, Harold Wright, Robert Marcellus, Richard Stoltzman, Jazz: Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Paquito D’Rivera, Eddie Daniels, Pete