Why Are Grimms' Fairy Tales So Mysteriously Enchanting?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shrek4 Manual.Pdf

Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including fl ashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms— children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these seizures. The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by taking the following precautions: Sit farther from the screen; use a smaller screen; play in a well-lit room; and do not play when you are drowsy or fatigued. If you or any of your relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. ESRB Game Ratings The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) ratings are designed to provide consumers, especially parents, with concise, impartial guidance about the age- appropriateness and content of computer and video games. This information can help consumers make informed purchase decisions about which games they deem suitable for their children and families. -

Who's Afraid of the Brothers Grimm?: Socialization and Politization Through Fairy Tales

Who's Afraid of the Brothers Grimm?: Socialization and Politization through Fairy Tales Jack Zipes The Lion and the Unicorn, Volume 3, Number 2, Winter 1979-80, pp. 4-41 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/uni.0.0373 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/247386 Access provided by University of Mary Washington & (Viva) (19 Sep 2017 17:43 GMT) Who's Afraid of the Brothers Grimm? Socialization and Politization through Fairy Tales Jack Zipes Over 170 years ago the Brothers Grimm began collecting original folk tales in Germany and stylized them into potent literary fairy tales. Since then these tales have exercised a pro- found influence on children and adults alike throughout the western world. Indeed, whatever form fairy tales in general have taken since the original publication of the Grimms' nar- ratives in 1812, the Brothers Grimm have been continually looking over our shoulders and making their presence felt. For most people this has not been so disturbing. However, during the last 15 years there has been a growing radical trend to over- throw the Grimms' benevolent rule in fairy-tale land by writers who believe that the Grimms' stories contribute to the creation of a false consciousness and reinforce an authoritarian sociali- zation process. This trend has appropriately been set by writers in the very homeland of the Grimms where literary revolutions have always been more common than real political ones.1 West German writers2 and critics have come to -

NIER's Rejection of the Heteronormative in Fairy

Cerri !1 “This Is Hardly the Happy Ending I Was Expecting”: NIER’s Rejection of the Heteronormative in Fairy Tales Video games are popularly viewed as a form of escapist entertainment with no real meaning or message. They are often considered as unnecessarily violent forms of recreation that possibly incite aggressive tendencies in their players. Overall, they are generally condemned as having no value. However, these beliefs are fallacious, as there is enormous potential in video games as not just learning tools but also as a source of literary criticism. Games have the capacity to generate criticisms that challenge established narratives through content and form. Thus, video games should be viewed as a new medium that demands serious analysis. Furthermore, the analysis generated by video games can benefit from being read through existing literary forms of critique. For example, the game NIER (2010, Cavia) can be read through a critical lens to evaluate its use of the fairy tale genre. More specifically, NIER can be analyzed using queer theory for the game’s reimagining and queering of the fairy tale genre. Queer theory, which grew prominent in the 1990s, is a critical theory that proposes a new way to approach identity and normativity. It distinguishes gender from biological sex, deconstructs the notion of gender as a male-female binary, and addresses the importance of performance in gender identification. That is, historically and culturally assigned mannerisms establish gender identity, and in order to present oneself with a certain gender one must align their actions with the expected mannerisms of that history and culture. -

Grimm's Fairy Stories

Grimm's Fairy Stories Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm The Project Gutenberg eBook, Grimm's Fairy Stories, by Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm, Illustrated by John B Gruelle and R. Emmett Owen This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Grimm's Fairy Stories Author: Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm Release Date: February 10, 2004 [eBook #11027] Language: English Character set encoding: US-ASCII ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GRIMM'S FAIRY STORIES*** E-text prepared by Internet Archive, University of Florida, Children, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team Note: Project Gutenberg also has an HTML version of this file which includes the original illustrations. See 11027-h.htm or 11027-h.zip: (http://www.ibiblio.org/gutenberg/1/1/0/2/11027/11027-h/11027-h.htm) or (http://www.ibiblio.org/gutenberg/1/1/0/2/11027/11027-h.zip) GRIMM'S FAIRY STORIES Colored Illustrations by JOHN B. GRUELLE Pen and Ink Sketches by R. EMMETT OWEN 1922 CONTENTS THE GOOSE-GIRL THE LITTLE BROTHER AND SISTER HANSEL AND GRETHEL OH, IF I COULD BUT SHIVER! DUMMLING AND THE THREE FEATHERS LITTLE SNOW-WHITE CATHERINE AND FREDERICK THE VALIANT LITTLE TAILOR LITTLE RED-CAP THE GOLDEN GOOSE BEARSKIN CINDERELLA FAITHFUL JOHN THE WATER OF LIFE THUMBLING BRIAR ROSE THE SIX SWANS RAPUNZEL MOTHER HOLLE THE FROG PRINCE THE TRAVELS OF TOM THUMB SNOW-WHITE AND ROSE-RED THE THREE LITTLE MEN IN THE WOOD RUMPELSTILTSKIN LITTLE ONE-EYE, TWO-EYES AND THREE-EYES [Illustration: Grimm's Fairy Stories] THE GOOSE-GIRL An old queen, whose husband had been dead some years, had a beautiful daughter. -

Introduction: Fairy Tale Films, Old Tales with a New Spin

Notes Introduction: Fairy Tale Films, Old Tales with a New Spin 1. In terms of terminology, ‘folk tales’ are the orally distributed narratives disseminated in ‘premodern’ times, and ‘fairy tales’ their literary equiva- lent, which often utilise related themes, albeit frequently altered. The term ‘ wonder tale’ was favoured by Vladimir Propp and used to encompass both forms. The general absence of any fairies has created something of a mis- nomer yet ‘fairy tale’ is so commonly used it is unlikely to be replaced. An element of magic is often involved, although not guaranteed, particularly in many cinematic treatments, as we shall see. 2. Each show explores fairy tale features from a contemporary perspective. In Grimm a modern-day detective attempts to solve crimes based on tales from the brothers Grimm (initially) while additionally exploring his mythical ancestry. Once Upon a Time follows another detective (a female bounty hunter in this case) who takes up residence in Storybrooke, a town populated with fairy tale characters and ruled by an evil Queen called Regina. The heroine seeks to reclaim her son from Regina and break the curse that prevents resi- dents realising who they truly are. Sleepy Hollow pushes the detective prem- ise to an absurd limit in resurrecting Ichabod Crane and having him work alongside a modern-day detective investigating cult activity in the area. (Its creators, Roberto Orci and Alex Kurtzman, made a name for themselves with Hercules – which treats mythical figures with similar irreverence – and also worked on Lost, which the series references). Beauty and the Beast is based on another cult series (Ron Koslow’s 1980s CBS series of the same name) in which a male/female duo work together to solve crimes, combining procedural fea- tures with mythical elements. -

Revenge and Punishment: Legal Prototype and Fairy Tale Theme

Circles: Buffalo Women's Journal of Law and Social Policy Volume 6 Article 4 1-1-1998 Revenge and Punishment: Legal Prototype and Fairy Tale Theme Kimberly J. Pierson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/circles Part of the Law Commons, and the Legal Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pierson, Kimberly J. (1998) "Revenge and Punishment: Legal Prototype and Fairy Tale Theme," Circles: Buffalo Women's Journal of Law and Social Policy: Vol. 6 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/circles/vol6/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Circles: Buffalo Women's Journal of Law and Social Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CIRCLES 1998 Vol. VI REVENGE AND PUNISHMENT: LEGAL PROTOTYPE AND FAIRY TALE THEME By Kimberly J. Pierson' The study of the interrelationship between law and literature is currently very much in vogue, yet many aspects of it are still relatively unexamined. While a few select works are discussed time and time again, general children's literature, a formative part of a child's emerging notion of justice, has been only rarely considered, and the traditional fairy tale2 sadly ignored. This lack of attention to the first examples of literature to which most people are exposed has had a limiting effect on the development of a cohesive study of law and literature, for, as Ian Ward states: It is its inter-disciplinary nature which makes children's literature a particularly appropriate subject for law and literature study, and it is the affective importance of children's literature which surely elevates the subject fiom the desirable to the necessary. -

Into the Woods Character Descriptions

Into The Woods Character Descriptions Narrator/Mysterious Man: This role has been cast. Cinderella: Female, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: G3. A young, earnest maiden who is constantly mistreated by her stepmother and stepsisters. Jack: Male, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: B2. The feckless giant killer who is ‘almost a man.’ He is adventurous, naive, energetic, and bright-eyed. Jack’s Mother: Female, age 50 to 65. Vocal range top: Gb5. Vocal range bottom: Bb3. Browbeating and weary, Jack’s protective mother who is independent, bold, and strong-willed. The Baker: Male, age 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: Ab2. A harried and insecure baker who is simple and loving, yet protective of his family. He wants his wife to be happy and is willing to do anything to ensure her happiness but refuses to let others fight his battles. The Baker’s Wife: Female, age: 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: F3. Determined and bright woman who wishes to be a mother. She leads a simple yet satisfying life and is very low-maintenance yet proactive in her endeavors. Cinderella’s Stepmother: Female, age 40 to 50. Vocal range top: F#5. Vocal range bottom: A3. The mean-spirited, demanding stepmother of Cinderella. Florinda And Lucinda: Female, 25 to 35. Vocal range top: Ab5. Vocal range bottom: C4. Cinderella’s stepsisters who are black of heart. They follow in their mother’s footsteps of abusing Cinderella. Little Red Riding Hood: Female, age 18 to 20. -

Fairy Tale Versions~

FAIRY TALES/FOLK TALES Fairy Tales are a type of folktale in which magic plays a great part. Compiled by Sheila Kirven GENERAL Anderson, Hans Christian Steadfast Tin Soldier Juv.A544ste Armstrong, Gerry The magic bagpipe Juv. 788.9 .A735m Browne, Anthony Into the Forest Juv. B882i (Story incorporates elements of familiar tales) Casserley, Anne Roseen Juv. 398.21 .C344r Chapman, Gaynor The Luck Child Juv. 398.21.C466l 1968 De Regniers, Beatrice Little Sister and the Month Brothers Juv. D431Li Schenk The House in the Wood and Other Old Fairy Stories Juv. 398.2.G864h Little Lit: Folklore and Fairy Tale Funnies Juv.398.21.F666 Hennessy, B. G. Once Upon a Time Map Book: Take a Tour Juv.H515o of Six Enchanted Lands (Peter Pan, Wizard of Oz, Alice in Wonderland, Jack and then Beanstalk, Aladdin, Snow White) Jacobs, Joseph The buried moon; a tale told by Joseph Jacobs. Juv. 398.21 .J17b Jacobs, Joseph Indian fairy tales Juv.398.2 .J17i 1969 MacDonald, George, The golden key Juv. M135g Matsutani, Miyoko, The crane maiden. Juv. 98.21 .M434c My Storytime Collection of First Favorite tales Juv. 398.2.M995 2002 O’Malley, Kevin Once upon a cool motorcycle dude Juv. O543o (Two classmates try to tell a fairy tale to their class with some imaginative twists to some well-known fairy tale elements!) Oxenbury, Helen. Helen Oxenbury nursery story book. Juv. 398.21 .O98h San Jose, Christine Little Match Girl Juv. 398.21.A544j San Souci, Robert D. White Cat Juv.398.21.SS229w 1990 Singer, Marilyn Follow Follow: A book of Reverso poems Juv.811.54.S617f (Poems -

Snow White’’ Tells How a Parent—The Queen—Gets Destroyed by Jealousy of Her Child Who, in Growing Up, Surpasses Her

WARNING Concerning Copyright Restrictions The copyright law of the United States (Title 1.7, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or reproduction. One of three specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes “fair use”, that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This policy is in effect for the following document: Fear of Fantasy 117 people. They do not realize that fairy tales do not try to describe the external world and “reality.” Nor do they recognize that no sane child ever believes that these tales describe the world realistically. Some parents fear that by telling their children about the fantastic events found in fairy tales, they are “lying” to them. Their concern is fed by the child’s asking, “Is it true?” Many fairy tales offer an answer even before the question can be asked—namely, at the very beginning of the story. For example, “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves” starts: “In days of yore and times and tides long gone. .” The Brothers Grimm’s story “The Frog King, or Iron Henry” opens: “In olden times when wishing still helped one. .” Such beginnings make it amply clear that the stories take place on a very different level from everyday “reality.” Some fairy tales do begin quite realistically: “There once was a man and a woman who had long in vain wished for a child.” But the child who is familiar with fairy stories always extends the times of yore in his mind to mean the same as “In fantasy land . -

Download PDF ^ the Three Feathers and Other Grimm Fairy Tales

E4EZ2UX9LS09 » Kindle » The Three Feathers and Other Grimm Fairy Tales (Paperback) Th e Th ree Feath ers and Oth er Grimm Fairy Tales (Paperback) Filesize: 6.06 MB Reviews Completely essential read pdf. It is definitely simplistic but shocks within the 50 % of your book. Its been designed in an exceptionally straightforward way which is simply following i finished reading through this publication in which actually changed me, change the way i believe. (Damon Friesen) DISCLAIMER | DMCA J7VNF6BTWRBI # Kindle < The Three Feathers and Other Grimm Fairy Tales (Paperback) THE THREE FEATHERS AND OTHER GRIMM FAIRY TALES (PAPERBACK) Caribe House Press, LLC, 2016. Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****.In The Three Feathers and Other Grimm Fairy Tales, translator Catherine Riccio-Berry has remained faithful to the original German folk tales while also demonstrating her own keen ear for the language of playful storytelling. These eighteen carefully selected narratives are among the most engaging to be found in the Grimm Brothers extensive collection. In addition to four classic stories--Snow White, Little Red Riding Hood, Rumpelstiltskin, and Cinderella--this modernized and highly accessible translation also includes a delightful variety of lesser-known tales that range in tone from silly to moralizing to outright violent. Complete list of stories in this collection: The Three Feathers Fitcher s Pheasant Snow White The Story of Hen s Death Little Brother and Little Sister Little Red Riding Hood Hans my Hedgehog Straw, Coal, and Bean The Earth Gnome Doctor Know-It-All Bearskin Mrs. Trudy Mr. Korb Rumpelstiltskin Faithful John The Selfish Son Spindle, Shuttle, and Needle Cinderella. -

Fairy Tales and Folklore Countries

Recommended Reading Fairy Tales and Folklore Title Call Number AR North America The Jack Tales J 398.2 Cha - Tomie dePaola's front porch tales & North… J 398.2 DeP 4.8/1 The People Could Fly J 398.2 Ham 4.3/4 Waynetta and the cornstalk: a Texas fairy… J 398.2 Ket 3.3/0.5 The Frog Princess: a Tlingit Legend… [Alaska] J 398.2 Kim 3.5/0.5 Davy Crockett gets hitched J 398.2 Mil 4.2/0.5 Sister tricksters: rollicking tales of clever… J 398.2 San - Bubba the cowboy prince: a fractured Texas… E Ket 3.8/0.5 Nacho and Lolita [Mexico] E Rya 4.4/0.5 The Stinky Cheese Man and other fairly stupid tales E Sci 3.4/0.5 The princess and the warrior: a tale of two… [Mexico] E Ton 4.3/0.5 Native American The girl who helped thunder and other… J 398.08997 Bru 5.2/3 The Great Ball Game: a Muskogee story J 398.2 Bru 3.1/0.5 Yonder Mountain: a Cherokee legend J 398.2 Bus 3.8/0.5 The man who dreamed of elk-dogs: & other… J 398.2 Gob - The gift of the sacred dog J 398.2 Gob 4.2/0.5 Snow Maker’s Tipi E Gob - Central/ South America The great snake: stories from the Amazon J 398.2 Tay 4.4/1 The sea serpent's daughter: a Brazilian legend J 398.21 Lip 4.0/0.5 The little hummingbird J 398.24 Yah - The night the moon fell: a Maya myth J 398.25 Mor 3.4/ 0.5 Europe The twelve dancing princesses J 398.2 Bar 4.9/0.5 The king with horse's ears and other…[Ireland] J 398.2 Bur - Hans my hedgehog: a tale from…[Germany] J 398.2 Coo 4.6/0.5 Updated September 2017 Recommended Reading Fairy Tales and Folklore Title Call Number AR Europe (continued) Little Roja Riding Hood [Spain] -

Rockin Snow White Script

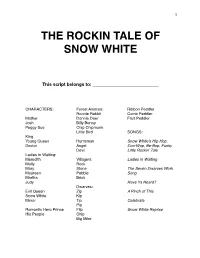

!1 THE ROCKIN TALE OF SNOW WHITE This script belongs to: __________________________ CHARACTERS: Forest Animals: Ribbon Peddler Roonie Rabbit Comb Peddler Mother Donnie Deer Fruit Peddler Josh Billy Bunny Peggy Sue Chip Chipmunk Little Bird SONGS: King Young Queen Huntsman Snow White’s Hip-Hop, Doctor Angel Doo-Wop, Be-Bop, Funky Devil Little Rockin’ Tale Ladies in Waiting: Meredith Villagers: Ladies in Waiting Molly Rock Mary Stone The Seven Dwarves Work Maureen Pebble Song Martha Brick Judy Have Ya Heard? Dwarves: Evil Queen Zip A Pinch of This Snow White Kip Mirror Tip Celebrate Pip Romantic Hero Prince Flip Snow White Reprise His People Chip Big Mike !2 SONG: SNOW WHITE HIP-HOP, DOO WOP, BE-BOP, FUNKY LITTLE ROCKIN’ TALE ALL: Once upon a time in a legendary kingdom, Lived a royal princess, fairest in the land. She would meet a prince. They’d fall in love and then some. Such a noble story told for your delight. ’Tis a little rockin’ tale of pure Snow White! They start rockin’ We got a tale, a magical, marvelous, song-filled serenade. We got a tale, a fun-packed escapade. Yes, we’re gonna wail, singin’ and a-shoutin’ and a-dancin’ till my feet both fail! Yes, it’s Snow White’s hip-hop, doo-wop, be-bop, funky little rockin’ tale! GIRLS: We got a prince, a muscle-bound, handsome, buff and studly macho guy! GUYS: We got a girl, a sugar and spice and-a everything nice, little cutie pie. ALL: We got a queen, an evil-eyed, funkified, lean and mean, total wicked machine.