Regional Innovation and Industrial Policies and Strategies - a Selective Comparative European Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teritoriální Uspořádání Policejních Složek V Zemích Evropské Unie: Inspirace Nejen Pro Českou Republiku II – Belgie, Dánsko, Finsko, Francie, Irsko, Itálie1 Mgr

Teritoriální uspořádání policejních složek v zemích Evropské unie: Inspirace nejen pro Českou republiku II – Belgie, Dánsko, Finsko, Francie, Irsko, Itálie1 Mgr. Oldřich Krulík, Ph.D. Abstrakt Po teoretickém „úvodním díle“ se ke čtenářům dostává pokračování volného seriálu o teritoriálním uspořádání policejních sborů ve členských státech Evropské unie. Kryjí nebo nekryjí se „policejní“ (případně i „hasičské“, justiční či dokonce „zpravodajské“) regiony s regiony, vytýčenými v rámci státní správy a samosprávy? Je soulad těchto územních prvků možné považovat za výjimku nebo za pravidlo? Jsou členské státy Unie zmítány neustálými reformami horizontálního uspořádání policejních složek, nebo si tyto systémy udržují dlouhodobou stabilitu? Text se nejprve věnuje „starým členským zemím“ Unie, a to pěkně podle abecedy. Řeč tedy bude o Belgii, Dánsku, Finsku, Francii, Irsku a Itálii. Klíčová slova Policejní síly, územní správa, územní reforma, administrativní mezičlánky Summary After the theoretical “introduction” can the readers to continue with the series describing the territorial organisation of the police force in the Member States of the European Union. Does the “police” regions coincide or not-coincide with the regions outlined in the state administration and local governments? Can the compliance of these local elements to be considered as an exception or the rule? Are the European Union Member States tossed about by constant reforms of the horizontal arrangement of police, or these systems maintain long-term stability? The text deals firstly -

Areal Og Befolkning

1 Areal og befolkning Tabel 1. Danmarks kystlinie, areal og befolkningstæthed. Coast line, area, and density of population. Kystlinie 1906' ArealI. april 1961 Befolknings- Folketal tæthed 26. sept. 1960 pr. km' Geografiske km' Geografiske km mil kv.mil 26. sept. 1960 1 3 4 5 0 A. Sjælland i alt ........................... 1 898,5 255,85 7 542,88 136,9 1 973 108 261,6 Københavns kommune ................... 67,8 9,14 83,38 1,5 721 381 8 651,7 Frederiksberg kommune .................. 8,70 0,2 114 285 13 136,2 Københavns amtsrådskreds ............... 183,1 24,68 493,46 9,0 486 139 985,2 Roskilde amtsrådskreds ................... 142,4 19,20 690,54 12,5 90 337 130,8 Frederiksborg amt ....................... 279,3 37,63 1 343,71 24,4 181 663 135,2 Holbæk amt ............................ 528,9 71,27 1 751,84 31,8 127 747 72,9 Sorø amts .............................. 211,9 28,55 1 478,60 26,8 129 580 87,6 Præstø amt ............................. 485,1 65,38 1692,65 30,7 121 976 72,1 B. Bornholm ............................... 158,3 21,34 587,55 10,7 48 373 82,3 C. Lolland-Falster .......................... 620,2 83,57 1 797,70 32,6 131 699 73,3 D. Fyn i alt ............................... 1 137,2 153,26 3482,10 63,3 413 908 118,9 Svendborg amt .......................... 633,6 85,39 1 666,51 30,3 149 163 89,5 Odense amtsrådskreds .................... 292,0 39,35 1 148,91 20,9 207273 180,4 Assens amtsrådskreds ..................... 211,6 28,52 666,68 12,1 57472 86,2 A-D. -

Connecting Øresund Kattegat Skagerrak Cooperation Projects in Interreg IV A

ConneCting Øresund Kattegat SkagerraK Cooperation projeCts in interreg iV a 1 CONTeNT INTRODUCTION 3 PROgRamme aRea 4 PROgRamme PRIORITIes 5 NUmbeR Of PROjeCTs aPPROveD 6 PROjeCT aReas 6 fINaNCIal OveRvIew 7 maRITIme IssUes 8 HealTH CaRe IssUes 10 INfRasTRUCTURe, TRaNsPORT aND PlaNNINg 12 bUsINess DevelOPmeNT aND eNTRePReNeURsHIP 14 TOURIsm aND bRaNDINg 16 safeTy IssUes 18 skIlls aND labOUR maRkeT 20 PROjeCT lIsT 22 CONTaCT INfORmaTION 34 2 INTRODUCTION a short story about the programme With this brochure we want to give you some highlights We have furthermore gathered a list of all our 59 approved from the Interreg IV A Oresund–Kattegat–Skagerrak pro- full-scale projects to date. From this list you can see that gramme, a programme involving Sweden, Denmark and the projects cover a variety of topics, involve many actors Norway. The aim with this programme is to encourage and and plan to develop a range of solutions and models to ben- support cross-border co-operation in the southwestern efit the Oresund–Kattegat–Skagerrak area. part of Scandinavia. The programme area shares many of The brochure is developed by the joint technical secre- the same problems and challenges. By working together tariat. The brochure covers a period from March 2008 to and exchanging knowledge and experiences a sustainable June 2010. and balanced future will be secured for the whole region. It is our hope that the brochure shows the diversity in Funding from the European Regional Development Fund the project portfolio as well as the possibilities of cross- is one of the important means to enhance this development border cooperation within the framework of an EU-pro- and to encourage partners to work across the border. -

A Meta Analysis of County, Gender, and Year Specific Effects of Active Labour Market Programmes

A Meta Analysis of County, Gender, and Year Speci…c E¤ects of Active Labour Market Programmes Agne Lauzadyte Department of Economics, University of Aarhus E-Mail: [email protected] and Michael Rosholm Department of Economics, Aarhus School of Business E-Mail: [email protected] 1 1. Introduction Unemployment was high in Denmark during the 1980s and 90s, reaching a record level of 12.3% in 1994. Consequently, there was a perceived need for new actions and policies in the combat of unemployment, and a law Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs) was enacted in 1994. The instated policy marked a dramatic regime change in the intensity of active labour market policies. After the reform, unemployment has decreased signi…cantly –in 1998 the unemploy- ment rate was 6.6% and in 2002 it was 5.2%. TABLE 1. UNEMPLOYMENT IN DANISH COUNTIES (EXCL. BORNHOLM) IN 1990 - 2004, % 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 Country 9,7 11,3 12,3 8,9 6,6 5,4 5,2 6,4 Copenhagen and Frederiksberg 12,3 14,9 16 12,8 8,8 5,7 5,8 6,9 Copenhagen county 6,9 9,2 10,6 7,9 5,6 4,2 4,1 5,3 Frederiksborg county 6,6 8,4 9,7 6,9 4,8 3,7 3,7 4,5 Roskilde county 7 8,8 9,7 7,2 4,9 3,8 3,8 4,6 Western Zelland county 10,9 12 13 9,3 6,8 5,6 5,2 6,7 Storstrøms county 11,5 12,8 14,3 10,6 8,3 6,6 6,2 6,6 Funen county 11,1 12,7 14,1 8,9 6,7 6,5 6 7,3 Southern Jutland county 9,6 10,6 10,8 7,2 5,4 5,2 5,3 6,4 Ribe county 9 9,9 9,9 7 5,2 4,6 4,5 5,2 Vejle county 9,2 10,7 11,3 7,6 6 4,8 4,9 6,1 Ringkøbing county 7,7 8,4 8,8 6,4 4,8 4,1 4,1 5,3 Århus county 10,5 12 12,8 9,3 7,2 6,2 6 7,1 Viborg county 8,6 9,5 9,6 7,2 5,1 4,6 4,3 4,9 Northern Jutland county 12,9 14,5 15,1 10,7 8,1 7,2 6,8 8,7 Source: www.statistikbanken.dk However, the unemployment rates and their evolution over time di¤er be- tween Danish counties, see Table 1. -

Canada, 1872-1901

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bieedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NEW DENMARK, NEW BRUNSWICK: NEW APPROACHES IN THE STUDY OF DANISH MIGRATION TO CANADA, 1872-1901 by Erik John Nielsen Lang, B.A. Hons., B.Ed., AIT A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Histoiy Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 25 April 2005 © 2005, Erik John Nielsen Lang Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Iodine, Inorganic and Soluble Salts

Iodine, inorganic and soluble salts Evaluation of health hazards and proposal of a health-based quality criterion for drinking water Environmental Project No. 1533, 2014 Title: Editing: Iodine, inorganic and soluble salts Elsa Nielsen, Krestine Greve, John Christian Larsen, Otto Meyer, Kirstine Krogholm, Max Hansen Division of Toxicology and Risk Assessment National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark Published by: The Danish Environmental Protection Agency Strandgade 29 1401 Copenhagen K Denmark www.mst.dk/english Year: ISBN no. Authored 2013. 978-87-93026-87-2 Published 2014. Disclaimer: When the occasion arises, the Danish Environmental Protection Agency will publish reports and papers concerning research and development projects within the environmental sector, financed by study grants provided by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency. It should be noted that such publications do not necessarily reflect the position or opinion of the Danish Environmental Protection Agency. However, publication does indicate that, in the opinion of the Danish Environmental Protection Agency, the content represents an important contribution to the debate surrounding Danish environmental policy. Sources must be acknowledged. 2 Iodine, inorganic and soluble salts Content CONTENT 3 PREFACE 5 1 GENERAL DESCRIPTION 6 1.1 IDENTITY 6 1.2 PRODUCTION AND USE 6 1.3 ENVIRONMENTAL OCCURRENCE AND FATE 7 1.3.1 Air 7 1.3.2 Water 7 1.3.3 Soil 8 1.3.4 Foodstuffs 10 1.3.5 Bioaccumulation 11 1.4 HUMAN EXPOSURE 11 2 TOXICOKINETICS 15 2.1 ABSORPTION 15 -

Denmark - on Your Bike! the National Bicycle Strategy

Denmark - on your bike! The national bicycle strategy July 2014 Ministry of Transport Frederiksholms Kanal 27 1220 Copenhagen K Denmark Telefon +45 41 71 27 00 ISBN 978-87-91511-93-6 [email protected] www.trm.dk Denmark - on your bike! The national bicycle strategy 4.| Denmark - on your bike! Denmark - on your bike! Published by: Ministry of Transport Frederiksholms Kanal 27F 1220 Copenhagen K Prepared by: Ministry of Transport ISBN internet version: 978-87-91511-93-6 Frontpage image: Danish Road Directorate Niclas Jessen, Panorama Ulrik Jantzen FOREWORD | 5v Foreword Denmark has a long tradition for cycling and that makes us somewhat unique in the world. We must retain our strong cycling culture and pass it on to our children so they can get the same pleasure of moving through traf- fic on a bicycle. Unfortunately, we cycle less today than we did previously. It is quite normal for Danes to get behind the wheel of the car, even for short trips. It is com- fortable and convenient in our busy daily lives. If we are to succeed in en- couraging more people to use their bicycles, therefore, we must make it more attractive and thus easier to cycle to work, school and on leisure trips. We can achieve this by, for example, creating better cycle paths, fewer stops, secure bicycle parking spaces and new cycling facilities. In the government, we are working for a green transition and we want to promote cycling, because cycling is an inexpensive, healthy and clean form of transport. The state has never before done as much in this regard as we are doing at present. -

Bi-Annual Progress Report IV ELENA-2012-038 June 15Th 2016 to December 15Th 2016

Bi-annual Progress Report IV ELENA-2012-038 June 15th 2016 to December 15th 2016 Table of Contents 1 Work Progress ............................................................................................ 2 1.1 Staff and recruitment ................................................................................... 2 1.2 Progress meetings with the municipalities .................................................. 2 1.3 Progress meetings within the Project Department ...................................... 2 1.4 Conferences and courses ........................................................................... 3 1.5 Task Groups ................................................................................................ 3 1.6 Cooperation with the other Danish ELENA projects ................................... 3 1.7 Secondments .............................................................................................. 4 1.8 Steering Committee ..................................................................................... 4 1.9 Advisory Group ............................................................................................ 5 1.10 New initiatives ............................................................................................. 5 2 Current status – implementation of the investment program ............... 6 2.1 The leverage factor ..................................................................................... 6 3 Identified Problems and Risks for Implementation ................................ 8 3.1 -

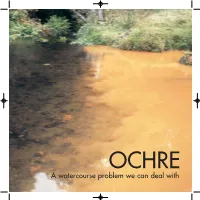

A Watercourse Problem We Can Deal with Contents Introduction

OCHRE A watercourse problem we can deal with Contents Introduction . Page 5 The path to good watercourses . Page 6 What is ochre? . Page 8 Why is ochre harmful? . Page 9 Where does ochre come from? . Page 11 The Ochre Act . Page 12 How is ochre combated? . Page 13 - Raising the water table . Page 13 - Ochre ponds . Page 14 - Winter ponds . Page 17 Are the measures effective? . Page 18 How to get started . Page 20 [3] Title: Ochre. A watercourse problem we can deal with Editor and text: Bent Lauge Madsen Idea and text proposals: Per Søby Jensen, Lars Aaboe Kristensen, Ole Ottosen, Søren Brandt, Poul Aagaard, Flemming Kofoed Translation: David I. Barry Photographs: Bent Lauge Madsen and Per Søby Jensen, Illustrations: Ribe County and Grafisk Tryk Lemvig-Thyborøn Layout and printing: Grafisk Tryk Lemvig-Thyborøn Publisher: Ringkjøbing County, Ribe County, Sønderjylland County, Herning Municipality, Holstebro Municipality Year of publication: 2005 Supported by: Danish Forest and Nature Agency The booklet is available free of charge, see www.okker.dk [4] Introduction Ochre poses an environmental problem in many watercourses in western and southern Jutland (the mainland part of Denmark). The red ochre makes the water turbid in streams and brooks. It covers the bed and coats the plants. Ochre pollution is more than just red ochre, though. It starts with acidic water and invisible, toxic iron that washes out into the watercourses. Neither fish nor macroinvertebra- tes can live in such water. If we are to ensure good-quality watercourses in Denmark it is not sufficient just to treat our waste- water. -

IDENTIFIERS England, Denmark, Sweden, and Holland Which Was

DOCUMENT REsopmE ED)16 79.7 PS 008 257 AUTHOR Hardqrove, Carol TITLE. Parent. Participation and Play Programs inHospitaSk Pediatrics in England, Sweden and Denmark.. SPONS AGENCY Panttmerican,Health Organization, Washington, D. C. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 73p. DR PRICE ifF-$0076 HC-$3.32 Plus Postage. ESRIPTORS. *Child Development; Family Involvement; Financi Support; *Foreign Countries; Furniture Design; Government Role; Hospitalized Children *Hospitals; *Parent Participation; *Play; Space Utilization; _Yolunteers IDENTIFIERS Denmark; England; Sweden ABSTRACT T. This paper presents the findings fro& a trip to England, Denmark, Sweden, and Holland which was desigied investigate how.hOspitals in these countries facilitate chifdren's healthy development during the stress of hospitalization. The areas specifically discussed are: J(1) initiating and reinforcing family involvement;(2) meeting childre ;'s need for play;(3) adapting space,,furnishihgs, and designs for parent and play programs; and (4) financing and publlcizing programs. Jnformation about the activities and functioning of government agencis, volunteer, and consumer advocate groups in each country are also included. (3MB) A ************************************ ************'********************** Documents acquired by ERIC inc ude many informal unpublished * *materials not available from ,o'the sources. ERIC makes_ every effort* *to obtain-the best copy AvailableNevertheless, items of marginal * *reproducibility are often encounte ed his affects the Auality * *of the microfiche and hardcopy -

Aarhus Sustainability Model 2 Introduktion Til Model Og Hvorfor Aarhus Sustainability Model Worldperfect

Second edition 2017 Aarhus Sustainability Model 2 Introduktion til model og hvorfor Aarhus Sustainability Model Worldperfect Colophon Table of contents Preface 5 ASM Version 2.0 6 Developing ASM 8 Text and concept: The Aarhus Process 10 Worldperfect and The four sections 16 Samsø Energiakademi Design and layout: 2017 and Sustainability 34 Worldperfect and Hele Vejen Cases 35 Theme photos: Worldperfect, Hele Vejen The European dimension Internationale 46 and Nina Wasland Cases 47 Aarhus 2017 DOKK 1, Hack Kampmanns Plads 2,2 Natural colours 52 8000 Aarhus C [email protected] Publikationen 54 4 Forord Aarhus Sustainability Model Aarhus Sustainability Model Preface 5 Aarhus 2017 Aarhus 2017 “Art and culture can act as catalysts for Preface: TBA sustainable development by bringing people together around big and small experiences alike, encouraging dialogue and demonstrating examples of intelligent, fun and alternative solutions to the challenges of tomorrow. We live in a world where the future is, as it always has been, uncertain. Complexity calls for new answers and this is where art and culture can deliver a blow to our conscience, encourage reflection over humanity’s relationship with nature, and provide inspiration for how we can live more sustainably. An art project that cleans the air in a park over Beijing can provoke a civil reaction demanding clean air and initiate political action. A plant wall can lead to a green movement within the city. Art and culture give us new eyes to see new opportunities.” - Aarhus 2017 6 Introduction Aarhus Sustainability Model Aarhus Sustainability Model Introduction 7 Aarhus 2017 Aarhus 2017 ASM version 2.0 Dear reader In this version, you can read into consideration. -

European Capital of Culture Aarhus 2017 / Strategic Business Plan Strategic Business Plan / Introduction 2 Aarhus 2017

Strategic Business Plan / Introduction 1 Aarhus 2017 European Capital of Culture Aarhus 2017 / Strategic Business Plan Strategic Business Plan / Introduction 2 Aarhus 2017 European Capital of Culture Aarhus 2017 / Strategic Business Plan 2015—2018 Date: December 2015 Editing: Rina Valeur Rasmussen, Head of Strategy and Operations, Aarhus 2017 Helle Erenbjerg, Communications Officer, Aarhus 2017 Design: Hele Vejen Cover photo: DOKK1. Photo: Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects Page 5 Rebecca Matthews. Photo: Michael Grøn, Billedmageren Print: Rådhustrykkeriet, 2nd. edition, 1000 copies ISBN: 978-87-998039-5-8 Under the patronage of Her Majesty the Queen European Capital of Culture Aarhus 2017 / Strategic Business Plan 2015—2018 Under the patronage of Her Majesty the Queen Strategic Business Plan / Introduction 2 Aarhus 2017 Her Majesty Queen Margrethe 2, April 2015, Aarhus. Photo: Brian Rasmussen Strategic Business Plan / Introduction 3 Aarhus 2017 Let’s create a fantastic year In 2017, Aarhus and the Central We can look forward to 2017 as the year Denmark Region will be the European where the Central Denmark Region will Capital of Culture. This is a project of be stimulated by a vast array of activi- both international and national scope, ties, with an inspiring arts programme, with happenings all over the Central international conferences and exciting Denmark Region and one of the most events. It will be a unique chance to ambitious cultural endeavours Den- release the region’s creativity and mark has been a part of for many years. innovation, and create new networks In 2017, we will celebrate our unique for many years to come. culture and values which make us who we are.