Disclosure's Effects: Wikileaks and Transparency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Periodicalspov.Pdf

“Consider the Source” A Resource Guide to Liberal, Conservative and Nonpartisan Periodicals 30 East Lake Street ∙ Chicago, IL 60601 HWC Library – Room 501 312.553.5760 ver heard the saying “consider the source” in response to something that was questioned? Well, the same advice applies to what you read – consider the source. When conducting research, bear in mind that periodicals (journals, magazines, newspapers) may have varying points-of-view, biases, and/or E political leanings. Here are some questions to ask when considering using a periodical source: Is there a bias in the publication or is it non-partisan? Who is the sponsor (publisher or benefactor) of the publication? What is the agenda of the sponsor – to simply share information or to influence social or political change? Some publications have specific political perspectives and outright state what they are, as in Dissent Magazine (self-described as “a magazine of the left”) or National Review’s boost of, “we give you the right view and back it up.” Still, there are other publications that do not clearly state their political leanings; but over time have been deemed as left- or right-leaning based on such factors as the points- of-view of their opinion columnists, the make-up of their editorial staff, and/or their endorsements of politicians. Many newspapers fall into this rather opaque category. A good rule of thumb to use in determining whether a publication is liberal or conservative has been provided by Media Research Center’s L. Brent Bozell III: “if the paper never met a conservative cause it didn’t like, it’s conservative, and if it never met a liberal cause it didn’t like, it’s liberal.” Outlined in the following pages is an annotated listing of publications that have been categorized as conservative, liberal, non-partisan and religious. -

In Re Motion of Propublica, Inc. for the Release of Court Records [FISC

IN RE OPINIONS & ORDERS OF THIS COURT ADDRESSING BULK COLLECTION OF DATA Docket No. Misc. 13-02 UNDER THE FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE ACT IN RE MOTION FOR THE RELEASE OF Docket No. Misc. 13-08 COURT RECORDS IN RE MOTION OF PROPUBLICA, INC. FOR Docket No. Misc. 13-09 THE RELEASE OF COURT RECORDS BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE THE REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS AND 25 MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS, IN SUPPORT OF THE NOVEMBER 6,2013 MOTION BY THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, ET AL, FOR THE RELEASE OF COURT RECORDS; THE OCTOBER 11, 2013 MOTION BY THE MEDIA FREEDOM AND INFORMATION ACCESS CLINIC FOR RECONSIDERATION OF THIS COURT'S SEPTEMBER 13, 2013 OPINION ON THE ISSUE OF ARTICLE III STANDING; AND THE NOVEMBER 12,2013 MOTION OF PRO PUBLICA, INC. FOR RELEASE OF COURT RECORDS Bruce D. Brown The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press 1101 Wilson Blvd., Suite 1100 Arlington, VA 22209 Counsel for Amici Curiae November 26. 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................... iii IDENTITY OF AMICI CURIAE .................................................................................................... 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ............................................................................................. 2 ARGUMENT ................................................................................................................................. -

CIA Best Practices in Counterinsurgency

CIA Best Practices in Counterinsurgency WikiLeaks release: December 18, 2014 Keywords: CIA, counterinsurgency, HVT, HVD, Afghanistan, Algeria, Colombia, Iraq, Israel, Peru, Northern Ireland, Sri Lanka, Chechnya, Libya, Pakistan, Thailand,HAMAS, FARC, PULO, AQI, FLN, IRA, PLO, LTTE, al-Qa‘ida, Taliban, drone, assassination Restraint: SECRET//NOFORN (no foreign nationals) Title: Best Practices in Counterinsurgency: Making High-Value Targeting Operations an Effective Counterinsurgency Tool Date: July 07, 2009 Organisation: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Author: CIA Office of Transnational Issues; Conflict, Governance, and Society Group Link: http://wikileaks.org/cia-hvt-counterinsurgency Pages: 21 Description This is a secret CIA document assessing high-value targeting (HVT) programs world-wide for their impact on insurgencies. The document is classified SECRET//NOFORN (no foreign nationals) and is for internal use to review the positive and negative implications of targeted assassinations on these groups for the strength of the group post the attack. The document assesses attacks on insurgent groups by the United States and other countries within Afghanistan, Algeria, Colombia, Iraq, Israel, Peru, Northern Ireland, Sri Lanka, Chechnya, Libya, Pakistan and Thailand. The document, which is "pro-assassination", was completed in July 2009 and coincides with the first year of the Obama administration and Leon Panetta's directorship of the CIA during which the United States very significantly increased its CIA assassination program at the -

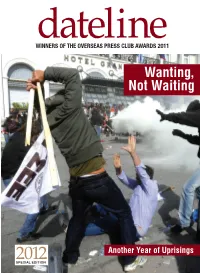

Wanting, Not Waiting

WINNERSdateline OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB AWARDS 2011 Wanting, Not Waiting 2012 Another Year of Uprisings SPECIAL EDITION dateline 2012 1 letter from the president ne year ago, at our last OPC Awards gala, paying tribute to two of our most courageous fallen heroes, I hardly imagined that I would be standing in the same position again with the identical burden. While last year, we faced the sad task of recognizing the lives and careers of two Oincomparable photographers, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, this year our attention turns to two writers — The New York Times’ Anthony Shadid and Marie Colvin of The Sunday Times of London. While our focus then was on the horrors of Gadhafi’s Libya, it is now the Syria of Bashar al- Assad. All four of these giants of our profession gave their lives in the service of an ideal and a mission that we consider so vital to our way of life — a full, complete and objective understanding of a world that is so all too often contemptuous or ignorant of these values. Theirs are the same talents and accomplishments to which we pay tribute in each of our awards tonight — and that the Overseas Press Club represents every day throughout the year. For our mission, like theirs, does not stop as we file from this room. The OPC has moved resolutely into the digital age but our winners and their skills remain grounded in the most fundamental tenets expressed through words and pictures — unwavering objectivity, unceasing curiosity, vivid story- telling, thought-provoking commentary. -

Foreign Terrorist Organizations

Order Code RL32223 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Foreign Terrorist Organizations February 6, 2004 Audrey Kurth Cronin Specialist in Terrorism Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Huda Aden, Adam Frost, and Benjamin Jones Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Foreign Terrorist Organizations Summary This report analyzes the status of many of the major foreign terrorist organizations that are a threat to the United States, placing special emphasis on issues of potential concern to Congress. The terrorist organizations included are those designated and listed by the Secretary of State as “Foreign Terrorist Organizations.” (For analysis of the operation and effectiveness of this list overall, see also The ‘FTO List’ and Congress: Sanctioning Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations, CRS Report RL32120.) The designated terrorist groups described in this report are: Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade Armed Islamic Group (GIA) ‘Asbat al-Ansar Aum Supreme Truth (Aum) Aum Shinrikyo, Aleph Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) Communist Party of Philippines/New People’s Army (CPP/NPA) Al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group, IG) HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement) Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) Hizballah (Party of God) Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) Jemaah Islamiya (JI) Al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamic Jihad) Kahane Chai (Kach) Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK, KADEK) Lashkar-e-Tayyiba -

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE PB 34-04-4 Volume 30 Number 4 October-December 2004 STAFF: FEATURES Commanding General Major General Barbara G

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE PB 34-04-4 Volume 30 Number 4 October-December 2004 STAFF: FEATURES Commanding General Major General Barbara G. Fast 8 Tactical Intelligence Shortcomings in Iraq: Restructuring Deputy Commanding General Battalion Intelligence to Win Brigadier General Brian A. Keller by Major Bill Benson and Captain Sean Nowlan Deputy Commandant for Futures Jerry V. Proctor Director of Training Development 16 Measuring Anti-U.S. Sentiment and Conducting Media and Support Analysis in The Republic of Korea (ROK) Colonel Eileen M. Ahearn by Major Daniel S. Burgess Deputy Director/Dean of Training Development and Support 24 Army’s MI School Faces TRADOC Accreditation Russell W. Watson, Ph.D. by John J. Craig Chief, Doctrine Division Stephen B. Leeder 25 USAIC&FH Observations, Insights, and Lessons Learned Managing Editor (OIL) Process Sterilla A. Smith by Dee K. Barnett, Command Sergeant Major (Retired) Editor Elizabeth A. McGovern 27 Brigade Combat Team (BCT) Intelligence Operations Design Director SSG Sharon K. Nieto by Michael A. Brake Associate Design Director and Administration 29 North Korean Special Operations Forces: 1996 Kangnung Specialist Angiene L. Myers Submarine Infiltration Cover Photographs: by Major Harry P. Dies, Jr. Courtesy of the U.S. Army Cover Design: 35 Deconstructing The Theory of 4th Generation Warfare Specialist Angiene L. Myers by Del Stewart, Chief Warrant Officer Three (Retired) Purpose: The U.S. Army Intelli- gence Center and Fort Huachuca (USAIC&FH) publishes the Military DEPARTMENTS Intelligence Professional Bulle- tin quarterly under provisions of AR 2 Always Out Front 58 Language Action 25-30. MIPB disseminates mate- rial designed to enhance individu- 3 CSM Forum 60 Professional Reader als’ knowledge of past, current, and emerging concepts, doctrine, materi- 4 Technical Perspective 62 MIPB 2004 Index al, training, and professional develop- ments in the MI Corps. -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

Strategic Implications of the Evolving Shanghai Cooperation Organization

The United States Army War College The United States Army War College educates and develops leaders for service at the strategic level while advancing knowledge in the global application of Landpower. The purpose of the United States Army War College is to produce graduates who are skilled critical thinkers and complex problem solvers. Concurrently, it is our duty to the U.S. Army to also act as a “think factory” for commanders and civilian leaders at the strategic level worldwide and routinely engage in discourse and debate concerning the role of ground forces in achieving national security objectives. The Strategic Studies Institute publishes national security and strategic research and analysis to influence policy debate and bridge the gap between military and academia. The Center for Strategic Leadership and Development CENTER for contributes to the education of world class senior STRATEGIC LEADERSHIP and DEVELOPMENT leaders, develops expert knowledge, and provides U.S. ARMY WAR COLLEGE solutions to strategic Army issues affecting the national security community. The Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute provides subject matter expertise, technical review, and writing expertise to agencies that develop stability operations concepts and doctrines. U.S. Army War College The Senior Leader Development and Resiliency program supports the United States Army War College’s lines of SLDR effort to educate strategic leaders and provide well-being Senior Leader Development and Resiliency education and support by developing self-awareness through leader feedback and leader resiliency. The School of Strategic Landpower develops strategic leaders by providing a strong foundation of wisdom grounded in mastery of the profession of arms, and by serving as a crucible for educating future leaders in the analysis, evaluation, and refinement of professional expertise in war, strategy, operations, national security, resource management, and responsible command. -

JULIAN ASSANGE: When Google Met Wikileaks

JULIAN ASSANGE JULIAN +OR Books Email Images Behind Google’s image as the over-friendly giant of global tech when.google.met.wikileaks.org Nobody wants to acknowledge that Google has grown big and bad. But it has. Schmidt’s tenure as CEO saw Google integrate with the shadiest of US power structures as it expanded into a geographically invasive megacorporation... Google is watching you when.google.met.wikileaks.org As Google enlarges its industrial surveillance cone to cover the majority of the world’s / WikiLeaks population... Google was accepting NSA money to the tune of... WHEN GOOGLE MET WIKILEAKS GOOGLE WHEN When Google Met WikiLeaks Google spends more on Washington lobbying than leading military contractors when.google.met.wikileaks.org WikiLeaks Search I’m Feeling Evil Google entered the lobbying rankings above military aerospace giant Lockheed Martin, with a total of $18.2 million spent in 2012. Boeing and Northrop Grumman also came below the tech… Transcript of secret meeting between Julian Assange and Google’s Eric Schmidt... wikileaks.org/Transcript-Meeting-Assange-Schmidt.html Assange: We wouldn’t mind a leak from Google, which would be, I think, probably all the Patriot Act requests... Schmidt: Which would be [whispers] illegal... Assange: Tell your general counsel to argue... Eric Schmidt and the State Department-Google nexus when.google.met.wikileaks.org It was at this point that I realized that Eric Schmidt might not have been an emissary of Google alone... the delegation was one part Google, three parts US foreign-policy establishment... We called the State Department front desk and told them that Julian Assange wanted to have a conversation with Hillary Clinton... -

092508 but He's a Muslim!

"But He's a Muslim!" | HuffPost US EDITION THE BLOG 09/25/2008 05:12 am ET | Updated May 25, 2011 “But He’s a Muslim!” By Marty Kaplan It made me think of my own family. Having coined “O’Bama” for the Irish working-class values that Joe Biden brings to the Democratic ticket, Chris Matthews called his family in Pennsylvania — where Scranton-born Biden is known as the state’s “third senator” in some quarters — to ask whether now they’d be voting for Obama. “But he’s a Muslim!” That’s the reply Matthews told his viewers he got. The Matthews clan is not alone. Going into the Democratic National Convention, depending on which poll you read, somewhere between 10 percent and 15 percent of American voters thought that Obama is a Muslim. A Newsweek poll found that 26 percent thought he was raised as a Muslim (untrue), and 39 percent thought he grew up going to an Islamic school in Indonesia (also untrue). I’m not shocked by Americans’ ability to think untrue things. After all, under the relentless tutelage of the Bush administration and its media enablers, nearly 70 percent of the country thought that Saddam Hussein was personally involved in planning the Sept. 11 attack. In fact, if you told me that double-digit percentages of voters believe that Jewish workers were warned to stay home on Sept. 11, or that the American landing on the moon was faked, or that every one of the words of the Bible is literally and absolutely true, I wouldn’t be a bit surprised. -

State of the Art in Lightweight Symmetric Cryptography

State of the Art in Lightweight Symmetric Cryptography Alex Biryukov1 and Léo Perrin2 1 SnT, CSC, University of Luxembourg, [email protected] 2 SnT, University of Luxembourg, [email protected] Abstract. Lightweight cryptography has been one of the “hot topics” in symmetric cryptography in the recent years. A huge number of lightweight algorithms have been published, standardized and/or used in commercial products. In this paper, we discuss the different implementation constraints that a “lightweight” algorithm is usually designed to satisfy. We also present an extensive survey of all lightweight symmetric primitives we are aware of. It covers designs from the academic community, from government agencies and proprietary algorithms which were reverse-engineered or leaked. Relevant national (nist...) and international (iso/iec...) standards are listed. We then discuss some trends we identified in the design of lightweight algorithms, namely the designers’ preference for arx-based and bitsliced-S-Box-based designs and simple key schedules. Finally, we argue that lightweight cryptography is too large a field and that it should be split into two related but distinct areas: ultra-lightweight and IoT cryptography. The former deals only with the smallest of devices for which a lower security level may be justified by the very harsh design constraints. The latter corresponds to low-power embedded processors for which the Aes and modern hash function are costly but which have to provide a high level security due to their greater connectivity. Keywords: Lightweight cryptography · Ultra-Lightweight · IoT · Internet of Things · SoK · Survey · Standards · Industry 1 Introduction The Internet of Things (IoT) is one of the foremost buzzwords in computer science and information technology at the time of writing. -

“We Will Crush You”

“We Will Crush You” The Restriction of Political Space in the Democratic Republic of Congo Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-405-2 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org November 2008 1-56432-405-2 “We Will Crush You” The Restriction of Political Space in the Democratic Republic of Congo Map of the Democratic Republic of Congo ................................................................ 1 I. Summary ............................................................................................................... 2 Methodology ....................................................................................................... 7 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................... 9 To the Congolese Government ............................................................................. 9 To the Congolese National Assembly and Senate .............................................. 10 To International Donors ..................................................................................... 10 To MONUC and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) 10 III.