Spiritual Science and the Modern Occult Revival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harry Collison, MA – Kingston University Working Paper ______

Harry Collison, MA – Kingston University Working Paper __________________________________________________________________________________________ HARRY COLLISON, MA (1868-1945): Soldier, Barrister, Artist, Freemason, Liveryman, Translator and Anthroposophist Sir James Stubbs, when answering a question in 1995 about Harry Collison, whom he had known personally, described him as a dilettante. By this he did not mean someone who took a casual interest in subjects, the modern usage of the term, but someone who enjoys the arts and takes them seriously, its more traditional use. This was certainly true of Collison, who studied art professionally and was an accomplished portraitist and painter of landscapes, but he never had to rely on art for his livelihood. Moreover, he had come to art after periods in the militia and as a barrister and he had once had ambitions of becoming a diplomat. This is his story.1 Collisons in Norfolk, London and South Africa Originally from the area around Tittleshall in Norfolk, where they had evangelical leanings, the Collison family had a pedigree dating back to at least the fourteenth century. They had been merchants in the City of London since the later years of the eighteenth century, latterly as linen drapers. Nicholas Cobb Collison (1758-1841), Harry’s grandfather, appeared as a witness in a case at the Old Bailey in 1800, after the theft of material from his shop at 57 Gracechurch Street. Francis (1795-1876) and John (1790-1863), two of the children of Nicholas and his wife, Elizabeth, née Stoughton (1764-1847), went to the Cape Colony in 1815 and became noted wine producers.2 Francis Collison received the prize for the best brandy at the first Cape of Good Hope Agricultural Society competition in 1833 and, for many years afterwards, Collison was a well- known name in the brandy industry. -

The Anthroposophic Art of Ernesto Genoni, Goetheanum, 1924

The Anthroposophic Art of Ernesto Genoni, Goetheanum, 1924 John Paull The images 1-16 were first exhibited at the exhibition, Angels of the First Class: The Anthroposophic Art of Ernesto Genoni, Goetheanum, 1924 held at: VITAL YEARS CONFERENCE 2016 – CRADLE OF A HEALTHY LIFE Date: Jul 5 2016 - Jul 9 2016 Venue: Tarremah Steiner School, Hobart, Tasmania Cover image: Image 1. Angels of the Cradle “In painting, too, Dr Steiner showed the way to a new ideal. He trained his pupils to experience the inner life of colour - out of the language of colours themselves - to give birth to form, without ever drawing in the forms beforehand. This was a difficult ideal to fulfil and it required the development of a new technique. But in the course of years a considerable number of artists, each in his individual way, have produced beautiful works in this direction Looking at some of these pictures, whether of human forms and groups, or sceneries of Nature, or more purely spiritual Imaginations, one experiences a kind of liberation; one feels one never realised before what the pure world of colour can convey. It is as though a new world were being opened” George Adams Kaufmann, 1933, p.46. Journal of Organics INTERNATIONAL, OPEN ACCESS, PEER REVIEWED, FREE A Special Issue devoted to an account of the Anthroposophic art of Ernesto Genoni, Australia’s pioneer of biodynamic and organic farming. Volume 3 Number 2, September 2016 jOrganics.org ISSN 2204-1060 eISSN 2204-1532 !2 Journal of Organics 3(2) 2016 !2 The Anthroposophic Art of Ernesto Genoni, Goetheanum, 1924 John Paull School of Land & Food, University of Tasmania [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Ernesto Genoni (1885-1975) was a pioneer of biodynamic and organic farming in Australia. -

Waldorf Education & Anthroposophy 2

WALDORF EDUCATION AND ANTHROPOSOPHY 2 [XIV] FOU NDAT IONS OF WALDORF EDUCAT ION R U D O L F S T E I N E R Waldorf Education and Anthroposophy 2 Twelve Public Lectures NOVEMBER 19,1922 – AUGUST 30,1924 Anthroposophic Press The publisher wishes to acknowledge the inspiration and support of Connie and Robert Dulaney ❖ ❖ ❖ Introduction © René Querido 1996 Text © Anthroposophic Press 1996 The first two lectures of this edition are translated by Nancy Parsons Whittaker and Robert F. Lathe from Geistige Zusammenhänge in der Gestaltung des Menschlichen Organismus, vol. 218 of the Complete Works of Rudolf Steiner, published by Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach, Switzerland, 1976. The ten remaining lectures are a translation by Roland Everett of Anthroposophische Menschenkunde und Pädagogik, vol. 304a of the Complete Works of Rudolf Steiner, published by Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach, Switzerland, 1979. Published by Anthroposophic Press RR 4, Box 94 A-1, Hudson, N.Y. 12534 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Steiner, Rudolf, 1861–1925. [Anthroposophische Menschenkunde und Pädagogik. English] Waldorf education and anthroposophy 2 : twelve public lectures. November 19, 1922–August 30, 1924 / Rudolf Steiner. p. cm. — (Foundations of Waldorf education ;14) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-88010-388-4 (pbk.) 1. Waldorf method of education. 2. Anthroposophy. I. Title. II. Series. LB1029.W34S7213 1996 96-2364 371.3'9— dc20 CIP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and articles. -

Academic and Social Effects of Waldorf Education on Elementary School Students

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 5-2018 Academic and Social Effects of Waldorf Education on Elementary School Students Christian Zepeda California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Early Childhood Education Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Educational Psychology Commons, Elementary Education Commons, Elementary Education and Teaching Commons, International and Comparative Education Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, and the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Zepeda, Christian, "Academic and Social Effects of Waldorf Education on Elementary School Students" (2018). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 272. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all/272 This Capstone Project (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects and Master's Theses at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: EFFECTS OF WALDORF EDUCATION 1 Academic and Social Effects of Waldorf Education on Elementary School Students Christian Zepeda Liberal Studies Department College of Education California State University Monterey Bay EFFECTS OF WALDORF EDUCATION 2 Abstract As society becomes more critical of public education, alternative education systems are becoming more popular. The Waldorf education system, based on the philosophy of Rudolf Steiner, has increased in popularity and commonality each decade. Currently, 23 Waldorf institutions exist in California. -

Ms. Tomer Rosen-Grace Harduf 1793000, D.N. Hamovil [email protected] Last Update: October 2016

Ms. Tomer Rosen-Grace Harduf 1793000, D.N. Hamovil [email protected] Last Update: October 2016 Tomer Rosen Grace, Translator, Copy editor & Proofreader CV, Anthroposophical and other Translation Projects, and relevant work experience Name: Tomer Yasmin Rosen Grace Born: 12 September 1968, Mother of 2. Currently living in Harduf Anthroposophic Community in the North of Israel. Over the past 25 years I have translated 15 books as well as articles from English and German into Hebrew, mostly in the areas of literature, Jewish and New Age spirituality, Anthroposophy, self help, parenting, couples help and new age psychology & channelling. Recently I also translated an 300-page autobiography from Hebrew into English. I have also written, illustrated and self-published 12 children's books in Hebrew to-date, with more intended in near future. The first of them I also translated into English and published on Amazon July 2015. Part of my expertise lies in presenting a well written translated text, i.e. I always edit my own text for accuracy and style, making sure each dot lies in its rightful place. In addition to translating, I also take editing and proof-reading works in Hebrew, concentrating on polishing-up the text in terms of style and spelling/punctuation, rather than re-writing it. Punctuation in Hebrew (Nikkud) is another skill I offer, as well as editing already-translated work from German or English, including comparing the translation to the original and correcting it as necessary. Translations and Editing of Anthroposophical Writings -

Table of Contents Introduction

Young School’s Guide 2018 Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 How to Use this Guide...................................................................................................................................... 2 Establishing a Community .............................................................................................................................. 3 AWSNA Principles for Waldorf Schools ........................................................................................................ 4 AWSNA Policies & Practices ............................................................................................................................. 6 Establishing a Healthy School in Light of AWSNA Principles ................................................................ 9 Independence and Self Reflection ................................................................................................................. 9 Articulated Decision-Making ......................................................................................................................... 9 Support for Faculty & Staff............................................................................................................................. 9 Articulated Educational Program ............................................................................................................... 10 Support -

NEWBOOKS by Rudolf Steiner and Related Authors SPRING 2020 to Order Direct from Booksource Call 0845 370 0067 Or Email: [email protected] 2

NEWBOOKS By Rudolf Steiner and related authors SPRING 2020 to order direct from Booksource call 0845 370 0067 or email: [email protected] 2 www.templelodge.com ORDER INFORMATION RUDOLF STEINER PRESS ORDER ADDRESS Rudolf Steiner Press is dedicated to making available BookSource the work of Rudolf Steiner in English translation. We 50 Cambuslang Rd, Glasgow G32 8NB have hundreds of titles available – as printed books, Tel: 0845 370 0067 ebooks and in audio formats. As a publisher devoted to (international +44 141 642 9192) anthroposophy, we continually commission translations of Fax: 0845 370 0068 previously-unpublished works by Rudolf Steiner and (international +44 141 642 9182) invest in re-translating, editing and improving our editions. E-mail: [email protected] We are also committed to publishing introductory books TRADE TERMS as well as contemporary research. Our translations are authorised by Rudolf Steiner’s estate in Switzerland, to Reduced discount under £30 retail (except CWO) whom we pay royalties on sales, thus assisting their critical United Kingdom: Post paid work. Do support us today by buying our books, or contact Abroad: Post extra us should you wish to sponsor specific titles or to support NON-TRADE ORDERS the charity with a gift or legacy. If you have difficulty ordering from a bookshop or our website you can order direct from BookSource. Send payment with order, sterling cheque/PO made out TEMPLE LODGE PUBLISHING to ‘BookSource’, or quote Visa, Mastercard or Eurocard number (and expiry date) or phone 0845 370 0067. Temple Lodge Publishing has made available new thought, ideas and research in the field of spiritual science for more UK: than a quarter of a century. -

Documentation of the Conference for 25 Years EMAS in September 2020

Between economic recovery and the European Green Deal Pathways for corporate sustainability management BETWEEN ECONOMIC RECOVERY AND THE EUROPEAN GREEN DEAL Legal Notice Published by The Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) Division G I 4, Environment and Economy, Sustainable Corporate Governance 11055 Berlin Email: [email protected] · Internet: www.bmu.de Editors The Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU): Division G I 4, Environment and Economy, Sustainable Corporate Governance: Annette Schmidt- Räntsch, Sascha Klapproth adelphi consult GmbH: Daniel Weiß Office of the German EMAS Advisory Board (UGA): Frank Kermann European Commission, Directorate-General Environment: Friederike Detry Text and content Daniel Weiß (adelphi), Frank Kermann (UGA) pertext, Berlin As at December 2020 Download www.bmu.de, search EMAS; www.emas.de/25 (conference short film) Table of contents Programme for the virtual conference on 29 September 2020 4 Introduction 7 Conference outcomes 8 → Florian Pronold, Parliamentary State Secretary at the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety 8 → Keynote by Kęstutis Sadauskas, Director of Circular Economy and Green Growth of the Directorate-General Environment of the European Commission 10 → Panel: Potential and challenges of sustainable business practices as drivers for overcoming current crises and transforming the economy 12 → Panel: Climate management and climate neutrality – Companies between -

Anthroposophy Is a Source of Spiritual Knowledge and a Practice of Inner Development. Through It One Seeks to Penetrate The

Anthroposophy is a source of spiritual knowledge and a practice of inner development. Through it one seeks to penetrate the mystery of our relationship with the spiritual world by searching for answers and insights that come through a schooling of one’s inner life. It draws, and strives to build on, the spiritual research of Rudolf Steiner, who maintained that every human being (Anthropos) has the inherent wisdom (Sophia) to solve the riddles of existence and to transform both self and society. Anthroposophy is a human oriented spiritual philosophy that reflects and speaks to the basic deep spiritual questions of humanity, to our basic artistic needs, to the need to relate to the world out of a scientific attitude of mind, and to the need to develop a relation to the world in complete freedom. It is a path of knowledge or spiritual research, developed on the basis of European idealistic philosophy, rooted in the philosophies of Aristotle, Plato, and Thomas Aquinas. It is primarily defined by its method of research, and secondly by the possible knowledge or experiences this leads to. From this perspective, anthroposophy can also be called spiritual science. As such, it is an effort to develop not only natural scientific, but also a spiritual scientific research on the basis of the idealistic tradition, in the spirit of the historical strivings, that have led to the development of modern science. On this basis, anthroposophy strives to bridge the clefts that have developed since the Middle Ages between the sciences, the arts and the spiritual strivings of humanity as the three main areas of human culture, and build the foundation for a synthesis of them for the future. -

Overview of Comments on Draft Community Herbal Monograph on Lavandula Angustifolia Miller, Aetheroleum (EMA/HMPC/143181/2010)

27 March 2012 EMA/HMPC/734381/2011 Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC) Overview of comments on draft Community herbal monograph on Lavandula angustifolia Miller, aetheroleum (EMA/HMPC/143181/2010) Table 1: Organisations and/or individuals that commented on the draft Community herbal monograph entry on Lavandula angustifolia Miller, aetheroleum as released for public consultation on 15 February 2011 until 15 August 2011 Organisations and/or individuals 1 AESGP, Brussels, Belgium 2 ESCOP, Exeter, United Kingdom 3 Dr. Willmar Schwabe GmbH & Co.KG, Karlsruhe, Germany 7 Westferry Circus ● Canary Wharf ● London E14 4HB ● United Kingdom Telephone +44 (0)20 7418 8400 Facsimile +44 (0)20 7418 8416 E-mail [email protected] Website www.ema.europa.eu An agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency, 2012. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Table 2: Discussion of comments General comments to draft document Interested Comment and Rationale Outcome party AESGP AESGP in principle welcomes the development of the above-mentioned Community herbal monograph which, by providing harmonised assessment criteria for Lavandula aetheroleum-containing products, should facilitate mutual recognition in Europe. We have the following specific comments. ESCOP ESCOP welcomes the draft Community herbal monograph on Lavender oil prepared by the Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). ESCOP would like to comment on one particular issue of this monograph and herewith raise a general point with regard to posology and information on the number of drops recommended for essential oils. Schwabe We agree that the peroral well-established use of Lavender oil is assessed to be The suggested changes are taken into consideration. -

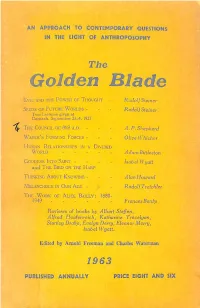

Golden Blade

AN APPROACH TO CONTEMPORARY QUESTIONS IN THE LIGHT OF ANTHROPOSOPHY The Golden Blade Evil and tme Power of Thought - Rudolf Steiner Seeds of Future Worlds - - - Rudolf Steiner Two Lectures given at noniach, September 23-4, 1921 The Council OF 869 A.D. - - - A. P. Shepherd Water's Forming Forces - - - Olive Whicher Human Relationships in a Divided World - _ . _ _ AdamBUtleston Goddess Into Saint . - . Isabel Wyatt and The Bird on the Harp T h i n k i n g A b o u t K n o w i n g - - - A l a n H o w a r d Melancholy IN Our Age - - - Rudolf Treichler The Work of Alice Bailey: 1880- 1 9 4 9 F r a n c e s B a n k s Reviews of books by Albert Steven, Alfred Heidenreich, Katharine Trevelyan, Stanley Drake, Evelyn Derry, Eleanor Merry, Isabel Wyatt. Edited by Arnold Freeman and Charles Waterman 1963 PUBLISHED ANNUALLY PRICE EIGHT AND SIX The Golden Blade 1963 Evil and the Power of Thought - Rudolf Steiner 1 S e e d s o f F u t u r e W o r l d s - - - R u d o l f S t e i n e r 1 1 Two Lectures given at Dornach, September 23-4, 1921 The Council OF 869 A.d. - - - A.P.Shepherd 22 W a t e r ' s F o r m i n g F o r c e s - - - O l i o e W h i c h e r 3 7 Human Relationships in a Divided World AdamBittleston 47 G o d d e s s I n t o S a i n t - - - . -

Vida Y Obra De Eugen Kolisko 255 Peter Selg

ABRIL · MAYO · JUNIO 2016 53 sumario Editorial 254 Joan Gasparin Vida y obra de Eugen Kolisko 255 Peter Selg Manual de Agrohomeopatía 269 Radko Tichavsky Joan Gamper 22 · 08014 BARCELONA TEL. 93 430 64 79 · FAX 93 363 16 95 [email protected] www.sociedadhomeopatica.com 253. Boletín53 Editorial Apreciado Socio/a, Este Boletín, está conformado por un interesante Dossier sobre Agroho- meopatía. Ha sido por casualidad que podamos contar con el profesor Radko Tichavsky, una de las personas que más está contribuyendo al desa- rrollo de la homeopatía para los cultivo y para las plantas. Creemos que es un profesional con unas ideas que van muy en la línea que seguimos en la escuela; y, además, es un tema poco desarrollado a nivel bi- bliográfico. Es por esta razón, que estamos muy contentos de poder contar con la posibilidad de organizar un Seminario sobre Holohomeopatía para la Agricultura, los próximos 23 y 24 de Julio. Estamos seguros que será una buena oportunidad de conocer a este maestro. Esperemos que nos pueda aclarar las dudas sobre la utilización de los remedios homeopáticos para la mejora y el rendimiento de las plantas. Hemos incluido también la biografía del matrimonio Kolísko. Fueron discí- pulos de Rudolf Steiner, pionero en la utilización de los remedios homeopá- ticos para las plantas; sus ideas de biodinámica son aún, hoy en día, de máxima actualidad. Los estudios de los austriacos Eugen y Lili Kolísko, y, posteriormente, de cientos de investigadores más, marcaron una línea científica en agrohomeopatía. Reciban un saludo. Joan Gasparin Presidente de la Sociedad Española Homeopatía Clásica .254 Boletín53 PETER SELG VIDA Y OBRA DE EUGEN KOLISKO 21.