THE LEGACY of INANNA Michael Orellana Andrews University This Research Is a Product of the Graduate Program in at Andrews University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asherah in the Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitic Literature Author(S): John Day Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol

Asherah in the Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitic Literature Author(s): John Day Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 105, No. 3 (Sep., 1986), pp. 385-408 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3260509 . Accessed: 11/05/2013 22:44 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 143.207.2.50 on Sat, 11 May 2013 22:44:00 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions JBL 105/3 (1986) 385-408 ASHERAH IN THE HEBREW BIBLE AND NORTHWEST SEMITIC LITERATURE* JOHN DAY Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford University, England, OX2 6QA The late lamented Mitchell Dahood was noted for the use he made of the Ugaritic and other Northwest Semitic texts in the interpretation of the Hebrew Bible. Although many of his views are open to question, it is indisputable that the Ugaritic and other Northwest Semitic texts have revolutionized our understanding of the Bible. One matter in which this is certainly the case is the subject of this paper, Asherah.' Until the discovery of the Ugaritic texts in 1929 and subsequent years it was common for scholars to deny the very existence of the goddess Asherah, whether in or outside the Bible, and many of those who did accept her existence wrongly equated her with Astarte. -

The Epic of Gilgamesh Humbaba from His Days Running Wild in the Forest

Gilgamesh's superiority. They hugged and became best friends. Name Always eager to build a name for himself, Gilgamesh wanted to have an adventure. He wanted to go to the Cedar Forest and slay its guardian demon, Humbaba. Enkidu did not like the idea. He knew The Epic of Gilgamesh Humbaba from his days running wild in the forest. He tried to talk his best friend out of it. But Gilgamesh refused to listen. Reluctantly, By Vickie Chao Enkidu agreed to go with him. A long, long time ago, there After several days of journeying, Gilgamesh and Enkidu at last was a kingdom called Uruk. reached the edge of the Cedar Forest. Their intrusion made Humbaba Its ruler was Gilgamesh. very angry. But thankfully, with the help of the sun god, Shamash, the duo prevailed. They killed Humbaba and cut down the forest. They Gilgamesh, by all accounts, fashioned a raft out of the cedar trees. Together, they set sail along the was not an ordinary person. Euphrates River and made their way back to Uruk. The only shadow He was actually a cast over this victory was Humbaba's curse. Before he was beheaded, superhuman, two-thirds god he shouted, "Of you two, may Enkidu not live the longer, may Enkidu and one-third human. As king, not find any peace in this world!" Gilgamesh was very harsh. His people were scared of him and grew wary over time. They pleaded with the sky god, Anu, for his help. In When Gilgamesh and Enkidu arrived at Uruk, they received a hero's response, Anu asked the goddess Aruru to create a beast-like man welcome. -

1 Inanna Research Script

INANNA RESEARCH SCRIPT (to be cut and shaped for performance) By Peggy Firestone Based on Translations of Clay Tablets from Sumer By Samuel Noah Kramer 1 [email protected] (773) 384-5802 © 2008 CAST OF CHARACTERS In order of appearance Narrators ………………………………… Storytellers & Timekeepers Inanna …………………………………… Queen of Heaven and Earth, Goddess, Immortal Enki ……………………………………… Creator & Organizer of Earth’s Living Things, Manager of the Gods & Goddesses, Trickster God, Inanna’s Grandfather An ………………………………………. The Sky God Ki ………………………………………. The Earth Goddess (also known as Ninhursag) Enlil …………………………………….. The Air God, inventor of all things useful in the Universe Nanna-Sin ………………………………. The Moon God, Immortal, Father of Inanna Ningal …………………………………... The Moon Goddess, Immortal, Mother of Inanna Lilith ……………………………………. Demon of Desolation, Protector of Freedom Anzu Bird ………………………………. An Unholy (Holy) Trinity … Demon bird, Protector of Cattle Snake that has no Grace ………………. Tyrant Protector Snake Gilgamesh ……………………………….. Hero, Mortal, Inanna’s first cousin, Demi-God of Uruk Isimud ………………………………….. Enki’s Janus-faced messenger Ninshubur ……………………………… Inanna’s lieutenant, Goddess of the Rising Sun, Queen of the East Lahamma Enkums ………………………………… Monster Guardians of Enki’s Shrine House Giants of Eridu Utu ……………………………………… Sun God, Inanna’s Brother Dumuzi …………………………………. Shepherd King of Uruk, Inanna’s husband, Enki’s son by Situr, the Sheep Goddess Neti ……………………………………… Gatekeeper to the Nether World Ereshkigal ……………………………. Queen of the -

The Epic of Gilgamesh: Tablet XI

Electronic Reserves Coversheet Copyright Notice The work from which this copy was made may be protected by Copyright Law (Title 17 U.S. Code http://www4.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/) The copyright notice page may, or may not, be included with this request. If it is not included, please use the following guidelines and refer to the U.S. Code for questions: Use of this material may be allowed if one or more of these conditions have been met: • With permission from the rights holder. • If the use is “Fair Use.” • If the Copyright on the work has expired. • If it falls within another exemption. **The USER of this is responsible for determining lawful uses** Montana State University Billings Library 1500 University Drive Billings, MT 59101-0298 (406) 657-1687 The Epic of Gilgamesh: Tablet XI The Story of the Flood Tell me, how is it that you stand in the Assembly of the Gods, and have found life!" Utanapishtim spoke to Gilgamesh, saying: "I will reveal to you, Gilgamesh, a thing that is hidden, a secret of the gods I will tell you! Shuruppak, a city that you surely know, situated on the banks of the Euphrates, that city was very old, and there were gods inside it. The hearts of the Great Gods moved them to inflict the Flood. Ea, the Clever Prince(?), was under oath with them so he repeated their talk to the reed house: 'Reed house, reed house! Wall, wall! O man of Shuruppak, son of Ubartutu: Tear down the house and build a boat! Abandon wealth and seek living beings! Spurn possessions and keep alive living beings! Make all living beings go up into the boat. -

Idolatry in the Ancient Near East1

Idolatry in the Ancient Near East1 Ancient Near Eastern Pantheons Ammonite Pantheon The chief god was Moloch/Molech/Milcom. Assyrian Pantheon The chief god was Asshur. Babylonian Pantheon At Lagash - Anu, the god of heaven and his wife Antu. At Eridu - Enlil, god of earth who was later succeeded by Marduk, and his wife Damkina. Marduk was their son. Other gods included: Sin, the moon god; Ningal, wife of Sin; Ishtar, the fertility goddess and her husband Tammuz; Allatu, goddess of the underworld ocean; Nabu, the patron of science/learning and Nusku, god of fire. Canaanite Pantheon The Canaanites borrowed heavily from the Assyrians. According to Ugaritic literature, the Canaanite pantheon was headed by El, the creator god, whose wife was Asherah. Their offspring were Baal, Anath (The OT indicates that Ashtoreth, a.k.a. Ishtar, was Baal’s wife), Mot & Ashtoreth. Dagon, Resheph, Shulman and Koshar were other gods of this pantheon. The cultic practices included animal sacrifices at high places; sacred groves, trees or carved wooden images of Asherah. Divination, snake worship and ritual prostitution were practiced. Sexual rites were supposed to ensure fertility of people, animals and lands. Edomite Pantheon The primary Edomite deity was Qos (a.k.a. Quas). Many Edomite personal names included Qos in the suffix much like YHWH is used in Hebrew names. Egyptian Pantheon2 Egyptian religion was never unified. Typically deities were prominent by locale. Only priests worshipped in the temples of the great gods and only when the gods were on parade did the populace get to worship them. These 'great gods' were treated like human kings by the priesthood: awakened in the morning with song; washed and dressed the image; served breakfast, lunch and dinner. -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Chapter X LAMASTU, DAUGHTER of ANU. a PROFILE

Chapter X LAMASTU, DAUGHTER OF ANU. A PROFILE F.A.M. Wiggermann Introduction and sources Outstanding among all supernatural evils defined by the ancient Mesopotamians is the child snatching demoness called Dimme in Sumerian, and Lamastu in Akkadian. I Whereas all other demons remain vague entities often operating in groups and hardly distinct from each other, DimmelLamastu has become a definite personality, with a mythology, an iconography, and a recognizable pattern of destructive action. The fear she obviously inspired gave rise to a varied set of counter measures, involving incantation rituals, herbs and stones, amulets, and the support of benevolent gods and spirits. These counter measures have left their traces in the archaeological record, the written and figurative sources from which a profile of the demoness can be reconstructed. Often the name of a demon or god gives a valuable clue to his (original) nature, but both Dimme and Lamastu have resisted interpretation. The reading of the Sumerian logogram dOiM(.ME) as Dim(m)e is indicated by graphemics: the ME wich is usually (but not always) added to the base doiM does not change the meaning, and must be a phonetic indicator. The presumed gloss' gab ask u (YOS 11 90:4, see Tonietti 1979:308) has been collated and reinterpreted (A. Cavigneaux, Z4 85 [1995] 170). The word may be identical with the Sumerian word for "corpse", "figurine", but this is far from certain, and does not clarify the behaviour of the demoness. Lamastu should be and could be a Semitic word, but the Akkadian lexicon does not offer a suitable root to derive it from. -

Ancient Mesopotamia Akkdadian Empire Reading Comprehension

ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA AKKDADIAN EMPIRE READING COMPREHENSION *Article *10 Matching Questions *10 True/False Questions *4 Multiple Choice Questions *Key Included Name____________________ ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA- AKKADIAN EMPIRE The Akkadian Empire was the first Empire to rule all of Mesopotamia. It lasted about 200 years from 2300 BC to 2100 BC. Originally the Sumerians lived in the southern part of Mesopotamia and the Akkadians lived in the northern part. They had similar governments and cultures, but spoke different languages. The governments had individual city-states, where each city had its own ruler that controlled the city and the surrounding area. The city-states were not initially united and often warred with one another. Eventually, the Akkadian rulers started to see the advantage to uniting many of their cities under a single nation and began forming alliances to work together. Sargon the Great rose to power around 2300 BC. According to Sumerian literature, Sargon was born to an Akkadian high priestess and a poor father, maybe a gardener. His mother abandoned him by putting him a reed woven basket and let it float down the river, like Moses a thousand years later. Sargon was rescued and made friends with the goddess Ishtar and was brought up in the king’s court. Sargon built himself a new city at Akkad and made himself the king of it when he grew up. He gradually conquered all the land around it, making the Akkadian Empire. The powerful Sumerian city of Uruk attacked Akkad, but they fought back and eventually conquered Uruk. Sargon went on to conquer all of the Sumerian city-states and united northern and southern Mesopotamia under a single ruler. -

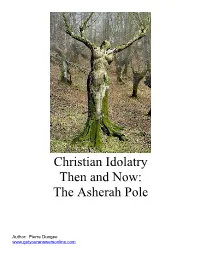

The Asherah Pole

Christian Idolatry Then and Now: The Asherah Pole Author: Pierre Dungee www.getyouranswersonline.com In this short book, we are going to look at the Asherah pole. Just so we have a working knowledge of idolatry, let’s look at what and idol is defined as: noun 1. a material object, esp a carved image, that is worshipped as a god 2. Christianity Judaism any being (other than the one God) to which divine honour is paid 3. a person who is revered, admired, or highly loved We also have the origin of this word, so let’s take a look at it here: o mid-13c., "image of a deity as an object of (pagan) worship," o from Old French idole "idol, graven image, pagan god," o from Late Latin idolum "image (mental or physical), form," used in Church Latin for "false god," o from Greek eidolon "appearance, reflection in water or a mirror," later "mental image, apparition, phantom,"also "material image, statue," from eidos "form" (see - oid). o Figurative sense of "something idolized" is first recorded 1560s (in Middle English the figurative sense was "someone who is false or untrustworthy"). Meaning"a person so adored" is from 1590s. From the origins of the word, you see the words ‘pagan’, ‘false god’, ‘statue’, so we can correctly infer that and idol is NOT a good thing that a Christian should be looking at or dealing with. The Lord has given strict instructions about idols as you can see in scripture here: Leviticus 26:1 - Ye shall make you no idols nor graven image, neither rear you up a standing image, neither shall ye set up any image of stone in your land, to bow down unto it: for I am the LORD your God. -

The Lost Book of Enki.Pdf

L0ST BOOK °f6NK1 ZECHARIA SITCHIN author of The 12th Planet • . FICTION/MYTHOLOGY $24.00 TH6 LOST BOOK OF 6NK! Will the past become our future? Is humankind destined to repeat the events that occurred on another planet, far away from Earth? Zecharia Sitchin’s bestselling series, The Earth Chronicles, provided humanity’s side of the story—as recorded on ancient clay tablets and other Sumerian artifacts—concerning our origins at the hands of the Anunnaki, “those who from heaven to earth came.” In The Lost Book of Enki, we can view this saga from a dif- ferent perspective through this richly con- ceived autobiographical account of Lord Enki, an Anunnaki god, who tells the story of these extraterrestrials’ arrival on Earth from the 12th planet, Nibiru. The object of their colonization: gold to replenish the dying atmosphere of their home planet. Finding this precious metal results in the Anunnaki creation of homo sapiens—the human race—to mine this important resource. In his previous works, Sitchin com- piled the complete story of the Anunnaki ’s impact on human civilization in peacetime and in war from the frag- ments scattered throughout Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Hittite, Egyptian, Canaanite, and Hebrew sources- —the “myths” of all ancient peoples in the old world as well as the new. Missing from these accounts, however, was the perspective of the Anunnaki themselves What was life like on their own planet? What motives propelled them to settle on Earth—and what drove them from their new home? Convinced of the existence of a now lost book that formed the basis of THE lost book of ENKI MFMOHCS XND PKjOPHeCieS OF XN eXTfCXUfCWJTWXL COD 2.6CHXPJA SITCHIN Bear & Company Rochester, Vermont — Bear & Company One Park Street Rochester, Vermont 05767 www.InnerTraditions.com Copyright © 2002 by Zecharia Sitchin All rights reserved. -

Death Attitudes and Perceptions of Death and Afterlife in Ancient Near Eastern Literature Leah Whitehead Craig Western Kentucky University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by TopSCHOLAR Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects Spring 2008 A Journey Into the Land of No Return: Death Attitudes and Perceptions of Death and Afterlife in Ancient Near Eastern Literature Leah Whitehead Craig Western Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Craig, Leah Whitehead, "A Journey Into the Land of No Return: Death Attitudes and Perceptions of Death and Afterlife in Ancient Near Eastern Literature" (2008). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 106. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/106 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Journey Into the Land of No Return: Death Attitudes and Perceptions of Death and Afterlife in Ancient Near Eastern Literature Leah Whitehead Craig Senior Honors Thesis Submitted to the Honors College of Western Kentucky University Spring, 2008 Approved by: _________________________________ _________________________________ -

Humbaba Research Packet.Pdf

HUMBABA Research Packet Compiled by Cassi Schiano and Christine Scarfuto CONTENTS: History of the Epic of Gilgamesh Summary of the Epic (and the Twelve Tablets) Character Info on Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and Humbaba Brief Historical Info: Babylon Ancient Rome The Samurai Colonial England War in Afghanistan 1 History of The Epic of Gilgamesh The Epic of Gilgamesh is epic poetry from Mesopotamia and is among the earliest known works of literature. The story revolves around a relationship between Gilgamesh (probably a real ruler in the late Early Dynastic II period ca. 27th century BC) and his close male companion, Enkidu. Enkidu is a wild man created by the gods as Gilgamesh's equal to distract him from oppressing the citizens of Uruk. Together they undertake dangerous quests that incur the displeasure of the gods. Firstly, they journey to the Cedar Mountain to defeat Humbaba, its monstrous guardian. Later they kill the Bull of Heaven that the goddess Ishtar has sent to punish Gilgamesh for spurning her advances. The latter part of the epic focuses on Gilgamesh's distressed reaction to Enkidu's death, which takes the form of a quest for immortality. Gilgamesh attempts to learn the secret of eternal life by undertaking a long and perilous journey to meet the immortal flood hero, Utnapishtim. Ultimately the poignant words addressed to Gilgamesh in the midst of his quest foreshadow the end result: "The life that you are seeking you will never find. When the gods created man they allotted to him death, but life they retained in their own keeping." Gilgamesh, however, was celebrated by posterity for his building achievements, and for bringing back long-lost cultic knowledge to Uruk as a result of his meeting with Utnapishtim.