For Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kejriwal-Ki-Kahani-Chitron-Ki-Zabani

केजरवाल के कम से परेशां कसी आम आदमी ने उनके ीमखु पर याह फेकं. आम आदमी पाट क सभाओं म# काय$कता$ओं से &यादा 'ेस वाले होते ह). क*मीर +वरोधी और भारत देश को खं.डत करने वाले संगठन2 का साथ इनको श5ु से 6मलता रहा है. Shimrit lee वो म8हला है िजसके ऊपर शक है क वो सी आई ए एज#ट है. इस म8हला ने केजरवाल क एन जी ओ म# कु छ 8दन रह कर भारत के लोकतं> पर शोध कया था. िजंदल ?पु के असल मा6लक एस िजंदल के साथ अAना और केजरवाल. िजंदल ?पु कोयला घोटाले म# शा6मल है. ये है इनके सेकु लCर&म का असल 5प. Dया कभी इAह# साध ू संत2 के साथ भी देखा गया है. मिलमु वोट2 के 6लए ये कु छ भी कर#गे. दंगे के आरो+पय2 तक को गले लगाय#गे. योगेAF यादव पहले कां?ेस के 6लए काम कया करते थे. ये पहले (एन ए सी ) िजसक अIयJ सोKनया गाँधी ह) के 6लए भी काम कया करते थे. भारत के लोकसभा चनावु म# +वदे6शय2 का आम आदमी पाट के Nवारा दखल. ये कोई भी सकते ह). सी आई ए एज#ट भी. केजरवाल मलायमु 6संह के भी बाप ह). उAह# कु छ 6सरफरे 8हAदओंु का वोट पDका है और बाक का 8हसाब मिलमु वोट से चल जायेगा. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 26 June 2006 I, Cira Guadalupe Parra hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Choral Conducting It is entitled: A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Stephen R. Coker___________ Dr. Earl G. Rivers_____________ Dr. Edward Nowacki_____________ _______________________________ _______________________________ A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor A document submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Ensembles and Conducting Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Cira Parra 620 Clinton Springs Ave Cincinnati, Ohio 45229 [email protected] B.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1987 M.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1989 Committee Chair: Stephen R. Coker ABSTRACT Modesta Bor (1926-98) was one of the outstanding Venezuelan composers, conductors, music educators and musicologists of the twentieth century. She wrote music for orchestra, chamber music, piano solo, piano and voice, and incidental music. She also wrote more than 95 choral works for mixed voices and 130 for equal-voice choir. Her style is a mixture of Venezuelan nationalism and folklore with European traits she learned in her studies in Russia. Chapter One contains a historical background of the evolution of Venezuelan art music since the colonial period, beginning in 1770. Knowing the state of art music in Venezuela helps one to understand the unusual nature of the Venezuelan choral movement that developed in the first half of the twentieth century. -

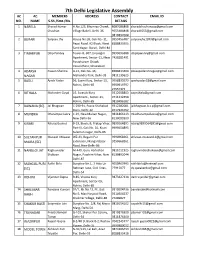

List of MLA Contact Details

7th Delhi Legislative Assembly AC AC MEMBERS ADDRESS CONTACT EMAIL ID NO. NAME S.Sh./Smt./Ms. DETAILS 1 NARELA Sharad Kumar H.No.123, Bhumiya Chowk, 8687686868 [email protected] Chauhan Village Bakoli, Delhi-36 9555484848 [email protected] 9818892004 2 BURARI Sanjeev Jha House No.09, Gali No.-11, 9953456787 [email protected] Pepsi Road, A2 Block, West 8588833505 Sant Nagar, Burari, Delhi-84 3 TIMARPUR Dilip Pandey Tower-B, 607, Dronagiri 9999696388 [email protected] Apartment, Sector-11, Near 7428281491 Parashuram Chowk Vasundhara, Ghaziabad 4 ADARSH Pawan Sharma A-13, Gali No.-36, 8588833404 [email protected] NAGAR Mahendra Park, Delhi-33 9811139625 5 BADLI Ajesh Yadav 56, Laxmi Kunj, Sector-13, 9958833979 [email protected] Rohini, Delhi-85 9990919797 27557375 6 RITHALA Mohinder Goyal 19, Swastik Kunj 9312658803 [email protected] Apartment., Sector-13, 9711332458 Rohini, Delhi-85 9810496182 7 BAWANA (SC) Jai Bhagwan C-290-91, Pucca Shahabad 9312282081 [email protected] Dairy, Delhi-42 9717921052 8 MUNDKA Dharampal Lakra C-29, New Multan Nagar, 9811866113 [email protected] New Delhi-56 8130099300 9 KIRARI Rituraj Govind B-19, Block,-B, Pratap Vihar, 9899564895 [email protected] Part-III, Gali No. 10, Kirari 9999654895 Suleman nagar, Delhi-86 10 SULTANPUR Mukesh Ahlawat WZ-43, Begum Pur 9990968261 [email protected] MAJRA (SC) Extension, Mangal Bazar 9250668261 Road, New Delhi-86 11 NANGLOI JAT Raghuvinder M-449, Guru Harkishan 9811011925 [email protected] -

Creating a Sustainable Main Street

Creating A Sustainable Main Street Woodbury, CT SDAT Report Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 1 MARKET 2 COMMUNITY DESIGN 12 ARTS & ARTISANS 34 MOBILITY & LIVABILITY 38 PLACEMAKING 50 MOVING FORWARD 58 TEAM ROSTER & THANKS 61 APPENDICES 64 INTRODUCTION • Inclusive and Participatory Processes. Public participation is the foundation of good community design. The SDAT involves a wide range of stakeholders and utilizes short feedback loops, resulting In December of 2014, Woodbury, CT submitted a proposal to the in sustainable decision-making that has broad public support and ownership. American Institute of Architects (AIA) for a Sustainable Design Assessment Team (SDAT) to assist the community and its citizens in • Objective Technical Expertise. The SDAT Team is assembled to include a range of technical addressing key issues facing the community. The issues included experts from across the country. Team Members do not accept payment for services and serve in economic development, mobility, and urban design. The AIA accepted a volunteer capacity on behalf of the AIA and the partner community. As a result, the SDAT Team the proposal and, after a preliminary visit by a small group in July has enhanced credibility with local stakeholders and can provide unencumbered technical advice. 2015, recruited a multi-disciplinary team of volunteers to serve on the • Cost Effectiveness.Through SDAT, communities are able to take advantage of leveraged resources SDAT Team. In October 2015, the SDAT Team members worked closely for their planning efforts. The AIA contributes up to $15,000 in financial assistance per project. The with local officials, community leaders, technical experts, non-profit SDAT team members volunteer their labor and expertise, allowing communities to gain immediate organizations and citizens to study the community and its concerns. -

English Polyphony and the Roman Church David Greenwood

caec1 1a English Polyphony and the Roman Church David Greenwood VOLUME 87, NO. 2 SUMMER, 1960 . ~5 EIGHTH ANNUAL LITURGICAL MUSIC WORKSHOP Flor Peeters Francis Brunner Roger Wagner Paul Koch Ermin Vitry Richard Schuler August 14-26, 1960 Inquire MUSIC DEPARTMENT Boys Town, Nebraska CAECILIA Published four times a year, Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter. Second-Class Postage Paid at Omaha, Nebraska. Subscription price--$3.00 per year All articles for publication must be in the hands of the editor, 3558 Cass St., Omaha 31, Nebraska, 30 days before month of publication. Business Manager: Norbert Letter Change of address should be sent to the circulation manager: Paul Sing, 3558 Cass St., Omaha 31, Nebraska Postmaster: Form 3579 to Caecilia, 3558 Cass St., Omaha 31, Nebr. CHANT ACCOMPANIMENTS by Bernard Jones KYRIE XVI " - .. - -91 Ky - ri - e_ * e - le -i - son. Ky - ri - e_ e - le - i - son •. " -.J I I I I J I I J I j I J : ' I I I " - ., - •· - - Ky-ri - e_ e - le -i - son. Chri-ste_ e - le -i - son. Chi-i-ste_ e - le- i - son.· I ( " .., I I j .Q. .0. I J J ~ ) : - ' ' " - - 9J Chri - ste_ e - le - i - son. Ky - ri - e __ e - le - i - son. " .., j .A - I I J J I I " - ., - . Ky -ri - e_ e - le - i - son. Ky- ri - e_* e -le - i - son. " I " I I I ~ I J I I J J. _J. J.,.-___ : . T T l I I M:SS Suppkmcnt to Caecilia Vol. 87, No. 2 SANCTUS XVI 11 a II I I I 2. -

Sound and Place at Central Public Squares in Belo Horizonte (Brazil)

Invisible Places 18–20JULY 2014, VISEU, PORTUGAL Polyphony of the squares: Sound and Place at Central Public Squares in Belo Horizonte (Brazil) Luiz Henrique Assis Garcia [email protected] Professor at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil Pedro Silva Marra [email protected] Phd candidate at Universidade Federal Fluminense,Belo Horizonte, Brazil Abstract This article aims to understand and compare the use of sounds and music as a tool to disput- ing, sharing and lotting space in two squares in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. In order to do so, citizens manipulate sounds and their parameters, such as intensity, frequency and spatiality. We refer to research data collected by Nucleurb/CCNM-UFMG constituted by a set of methodological procedures that involve field observation, sound recording, photo- graphs, field notesand research on archives, gathering and cross analyzing texts, pictures and sounds, in order to grasp the dynamics of conformation of “place” within the urban space. Keywords: Sonorities, Squares, Urban Space provisional version 1. Introduction A street crier screams constantly, as pedestrians pass by him, advertising a cellphone chip store’s services. During his intervals, another street crier asks whether people want to cut their hair or not. On the background, a succession of popular songs are played on a Record store, and groups of friends sitting on benches talk. An informal math teacher tries to sell a DVD in which he teaches how to solve fastly square root problems. The other side of the square, beyond the crossing of two busy avenues, Peruvian musicians prepare their con- cert, connecting microfones and speakers through cables, as street artists finish their circus presentation. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: PRISMS and POLYPHONY

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: PRISMS AND POLYPHONY: THE LIVED EXPERIENCES OF HIGH SCHOOL BAND STUDENTS AND THEIR DIRECTOR AS THEY PREPARE FOR AN ADJUDICATED PERFORMANCE Stephen W. Miles Doctor of Philosophy, 2012 Dissertation directed by: Professor Francine Hultgren Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership College of Education University of Maryland This hermeneutic phenomenological inquiry is called by the question: What are the lived experiences of high school band students and their director as they prepare for an adjudicated performance? While there are many lenses through which the phenomenon of music preparation and music making has been explored, a relatively untapped aspect of this phenomenon is the experience as lived by the students themselves. The experiences and behaviors of the band director are so inexorably intertwined with the student experience that this essential contextual element is also explored as a means to understand the phenomenon more fully. Two metaphorical constructs – one visual, one musical – provide a framework upon which this exploration is built. As a prism refracts a single color of light into a wide spectrum of hues, views from within illumine a variety of unique perspectives and uncover both divergent and convergent aspects of this experience. Polyphony (multiple contrasting voices working independently, yet harmoniously, toward a unified musical product) enables understandings of the multiplicity of experiences inherent in ensemble performance. Conversations with student participants and their director, notes from my observations, and journal offerings provide the text for phenomenological reflection and interpretation. The methodology underpinning this human science inquiry is identified by Max van Manen (2003) as one that “involves description, interpretation, and self-reflective or critical analysis” (p. -

May 2018 Newsletter

YOUR MONTHLY GUIDE TO PORT’S LIBRARY BOOKINGS MAY 2018 HARMONY AND HUMANITY WITH THE LEVINS QUICK READS Wednesday, May 16 at 7:30 p.m. Holiday hours Known for their sun-splashed songwriting that celebrates The library will be closed over our common humanity, The Levins were 2016 Northeast Memorial Day weekend: Satur- Regional Folk Alliance (NERFA) Formal Showcase Artists and day, May 26 through Monday, were voted 2014 Falcon Ridge Emerging Artists. May 28. The Levins’ recordings have garnered them invitations to Port Fest perform in Amsterdam, England, and throughout the U.S. They have received recognition and numerous songwrit- Visit the library’s booth at this ing awards in the Children’s, Jewish, Folk, and Indie music fun community gathering! Meet communities. Their unique harmonies and tightly blended and chat with staff, learn about unison vocals, along with their guitar and piano interplay, the latest library offerings, see reflect the couple’s own musical and personal relationship. some new tech, and find ac- tivities for kids. Saturday, May Their 2015 release Trust debuted in the Top 10 Folk chart 19 from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. on and the Top 20 Roots chart. Tom Staudter of The New York the track between Weber and Times wrote that the album “underscores positive mes- Schreiber. sages of love, peace, and self-awareness. Each tune serves as another stepping stone toward a better day and a richer FOL Book & Author life.” The disc’s title song, “Trust,” was a Top 10 song of 2015 Luncheon for WFUV’s John Platt, who said, “The Levins speak to our There’s still time to reserve your better selves with their crystalline harmonies and uplifting seat—but hurry! The Friends of lyrics.” the Library’s 49th Annual Book & Author Luncheon is on Friday, May 11 at 11 a.m. -

Emplacing and Excavating the City: Art, Ecology, and Public Space in New Delhi

Transcultural Studies 2015.1 75 Emplacing and Excavating the City: Art, Ecology, and Public Space in New Delhi Christiane Brosius, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Every claim on public space is a claim on the public imagination. It is a response to the questions: What can we imagine together?… Are we, in fact, a collective; is the collective a site for the testing of alternatives, or a ground for mobilising conformity? (Adajania 2008) Introduction Contemporary art production can facilitate the study of a city’s urban fabric, its societal change, and its cultural meaning production; this is particularly the case when examining exhibition practices and questions of how, why, when, where, and by whom artworks came to be emplaced and connected to certain themes and concepts.* Emplacement here refers to the process of constructing space for certain events or activities that involve sensory and affective aspects (Burrell and Dale 2014, 685). Emplacing art thus concerns a particular and temporary articulation of and in space within a relational set of connections (rather than binaries). In South Asia, where contemporary “fine art”1 is still largely confined to enclosed spaces like the museum or the gallery, which seek to cultivate a “learned” and experienced audience, the idea of conceptualising art for and in rapidly expanding and changing cities like Delhi challenges our notions of place, publicness, and urban development. The particular case discussed here, the public art festival, promises—and sets out—to explore an alternative vision of the city, alternative aspirations towards “belonging to and participating in” it.2 Nancy Adajania’s question “What can we imagine together” indirectly addresses which repositories and languages are available and can be used for such a joint effort, and who should be included in the undertaking. -

Environmental Movements by Women

ENVIRONMENTAL MOVEMENTS BY WOMEN Dr. Badiger Suresh & B. Kattimani Dept. of Women Studies Gulbara University Gulbarga Especially interesting is the leading role women played in the nation‟s early environmental movement. This movement began at least a century and a half ago, peaked in the Progressive era of the 1890s, and then declined during the war years in the early- to mid-20th century. Environmental movements of various countries have emerged due to different reasons. It is basically due to prevailing environmental quality of the locality. The environmental movements in the north are basically on the issue of quality of life. Whereas the environment movements in the south arise due to some other reasons, such as due to conflicts for controling of natural resources and many more. It is being said that the, environmental movements in India The participants of these movements in North are the middle class and upper class women, who have concern for the nature. But protesters are generally the marginal population – hill peasants, tribal communities, fishermen and other underprivileged people. The different environmental movements in our own country support this argument. The examples could be taken as Chipko, N.B.A Movements. Mitti Bachao Movements Andolan, Koel-Karo Movements(Andolan) and Green Belt Movements ( Andolana) Narmada Bachao Movements Andolan etc. That is why the environmentalism of the is refereed as “full stomach” environmentalism and the environmentalism of the south is called as “empty – belly” environmentalism. Chipko movement (Andolan) One of the first environmentalist movement which was inspired by women was the Chipko movement (Women tree-huggers in India). -

Download Survey Written Responses

Family Members What place or memorial have you seen that you like? What did you like about it? 9/11 memorial It was inclusive, and very calming. 9/11 Memorial It was beautiful. Park with a wall with names on it. Angels status. Water fountain. Water fountain area and location. Touchscreen info individual memorials Oklahoma City Memorial memorabilia collections 9-11 memorial Place to reflect and remember; reminder of the lessons we should Several Washington DC memorials learn from hateful acts Love that all the names were 911 New York City Place on a water fall Before the 911 Memorial was erected; I visited the site a month after the event. I liked its raw state; film posters adverts still hanging up from films premiered months prior. The brutal reality of the site in baring its bones. The paper cranes left by the schoolchildren. The Holocaust Museum along with the Anne Frank Haus spoke to me; the stories behind the lives of these beautiful people subjected to nothing but hate for who they loved and who they were. The educational component to the Holocaust Museum in D.C. spoke volumes to me. To follow the journey of a Holocaust victim... For Pulse, I see a blend of all of this. To learn the stories of why so many sought refuge and enjoyment there. Why did so many leave their "families"? Because they could not be who they were. I find it is important that we teach this lesson-it's okay to be who you are-we have your back-we love you-we will dance with you-in any form of structure. -

TOM LOESER DEPARTMENT of ART 2826 Lakeland Ave 6241

TOM LOESER DEPARTMENT OF ART 2826 Lakeland Ave 6241 Humanities Building Madison, WI 53704 University of Wisconsin-Madison Mobile: 608-345-6573 Madison, WI 53706 Email: [email protected] www.tomloeser.com EDUCATION 1992 MFA, University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth, Dartmouth, MA 1983 BFA, Furniture Design, Boston University, Boston, MA 1979 BA, Sociology and Anthropology, Haverford College, Haverford, PA ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2002-present Professor of Art, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 2017 Program Leader, UW in London Program 2009-2014 Department Chair, Art Department, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1996-2002 Associate Professor of Art, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 1992-1996 Assistant Professor of Art, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 1991-1992 Instructor, Art Department, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 1989-1990 Adjunct Professor, California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, CA 1988 Instructor, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI 1987 Instructor, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI 1987 Instructor, Swain School of Design, New Bedford, MA HONORS AND AWARDS 2015-present University of Wisconsin, Vilas Research Professor 2015-2020 University of Wisconsin, WARF Named Professorship 2013 Wisconsin Visual Art Lifetime Achievement Award, awarded by the Museum of Wisconsin Art, Wisconsin Visual Artists and the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences. 2012 Elected to American Craft Council College of Fellows 2006 Wisconsin Arts Board Visual Arts Fellowship 2006 University of Wisconsin Kellett Mid-Career Award 2004