Charles S. Maier Harvard University an American Empire?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Fragmentation in Conflict and Its Impact on Prospects for Peace

oslo FORUM papers N°006 - December 2016 Understanding fragmentation in conflict and its impact on prospects for peace Kathleen Gallagher Cunningham www.hd centre.org – www.osloforum.org Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue 114, Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva | Switzerland t : +41 22 908 11 30 f : +41 22 908 11 40 [email protected] www.hdcentre.org Oslo Forum www.osloforum.org The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) is a private diplo- macy organisation founded on the principles of humanity, impartiality and independence. Its mission is to help pre- vent, mitigate, and resolve armed conflict through dialogue and mediation. © 2016 – Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue Reproduction of all or part of this publication may be author- ised only with written consent and acknowledgment of the source. Kathleen Gallagher Cunningham Associate Professor at the Department of Government and Politics, University of Maryland [email protected] http://www.kathleengallaghercunningham.com Table of contents INTRODUCTION 2 1. WHAT IS FRAGMENTATION? 3 Fragmented actors 3 Multiple actors 3 Identifying fragmentation 4 New trends 4 The causes of fragmentation 5 2. THE CONSEQUENCES OF FRAGMENTATION FOR CONFLICT 7 Violence 7 Accommodation and war termination 7 Side switching 8 3. HOW PEACE PROCESSES AFFECT FRAGMENTATION 9 Coalescing 9 Intentional fragmentation 9 Unintentional fragmentation 9 Mediation 10 4. RESPONSES OF MEDIATORS AND OTHER THIRD-PARTY ACTORS TO FRAGMENTATION 11 Negotiations including all armed groups 11 Sequential negotiations 11 Inclusion of unarmed actors and national dialogue 12 Efforts to coalesce the opposition 13 5. AFTER SETTLEMENT 14 CONCLUSION 15 ENDNOTES 16 2 The Oslo Forum Papers | Understanding fragmentation in conflict Introduction Complicated conflicts with many disparate actors have cators of fragmentation, new trends, and a summation of why become increasingly common in the international system. -

Preserving the Long Peace in Asia the Institutional Building Blocks of Long-Term Regional Security

REPORT Preserving the Long Peace in Asia The Institutional Building Blocks of Long-Term Regional Security Independent Commission on Regional Security Architecture Preserving the Long Peace in Asia The Institutional Building Blocks of Long-Term Regional Security SEPTEMBER 2017 A REPORT OF THE ASIA SOCIETY POLICY INSTITUTE INDEPENDENT COMMISSION ON REGIONAL SECURITY ARCHITECTURE With a solution-oriented mandate, the Asia Society Policy Institute tackles major policy challenges confronting the Asia-Pacific in security, prosperity, sustainability, and the development of common norms and values for the region. The Asia Society Policy Institute is a think- and do-tank designed to bring forth policy ideas that incorporate the best thinking from top experts in Asia and to work with policy makers to integrate these ideas and put them into practice. ABOUT THE INDEPENDENT COMMISSION ON REGIONAL SECURITY ARCHITECTURE This report represents a consensus view of the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Independent Commission on Regional Security Architecture. By serving as signatories to the report, Commissioners have signaled their endorsement of the major findings and recommendations in the document. Commissioners were not, however, expected to concur with every statement in the report. Members of the Commission participated in this study in their personal capacity, and their endorsement does not reflect any official position of the organizations with which they are affiliated. Commission members are: CHAIR Kevin Rudd, President of the Asia Society Policy -

Colloquy Issue 1

peace colloquy The Joan B. Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies University of Notre Dame Issue No. 1, Spring 2002 Peacekeeping: Defining Success A NTHONY L AKE The Fundamentalist Factor S COTT A PPLEBY Economic Causes of Civil Wars P AUL C OLLIER peace colloquy 2 From the Editor s anyone who has visited the Kroc Institute can attest, the place is abuzz with discussions of peace. This dialogue emerges in part from the diverse array of people who cross paths at the Kroc Institute. At the heart of the conversation are scholars in a variety of fields, both at Notre Dame and other institutions. Through analyses of cultural, political, religious, and ethical Adimensions of current international conflicts, they provoke new insights into the meaning and prospects for peace. Peacebuilding practitioners working on the ground around the world, including many of our students and alumni, bring another set of questions to the discussion. These voices challenge us to think concretely about how peace can be fostered through conflict resolution, human rights, human development, refugee assistance, and other peacebuilding programs. The Institute also has contacts with international policymakers at the UN, State Department, World Bank, and other institutions, who direct our attention to the need for more equitable and effective global strategies for peace. By bringing together these and many other voices, the Kroc Institute has become the focal point for an engag- ing colloquy — or “serious discussion” — on peace. As its name suggests, each issue of peace colloquy seeks to highlight important contributions to this ongoing dialogue through feature articles by faculty, visiting lecturers, and alumni. -

Globalization and the Diffusion of Military Capabilities

GLOBALIZATION AND THE DIFFUSION OF MILITARY CAPABILITIES by Eddie Stokes A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science Boise State University December 2019 © 2019 Eddie Stokes ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Eddie Stokes Thesis Title: Globalization and the Diffusion of Military Capabilities Date of Final Oral Examination: 07 October 2019 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Eddie Stokes, and they evaluated their presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Michael A. Allen, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Ross Burkhart, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Stephen Utych, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Michael A. Allen, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved by the Graduate College. DEDICATION To my parents Ed and Tracey Stokes, none of this would have been possible if not for your endless emotional, intellectual, and financial support. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank my parents, Ed and Tracey Stokes, for their immense support over the course of this long process. I would next like to thank Dr. Michael A. Allen for his patience in helping me navigate the intricacies associated with writing this thesis. My sincere thanks also go to Dr. Stephen Utych and Dr. Ross Burkhart, who were so kind as to always find time in their busy schedules to meet with me and help me work through rigorous theoretical and analytical problems. -

Peacekeeping and the Peacekept Questions, Definitions, and Research Design

One PEACEKEEPING AND THE PEACEKEPT QUESTIONS, DEFINITIONS, AND RESEARCH DESIGN The Questions IN COUNTRIES WRACKED BY CIVIL WAR, the international com munity is frequently called upon to deploy monitors and troops to try to keep the peace. The United Nations, regional organizations, and some times ad hoc groups of states have sent peacekeepers to high-profile trou ble-spots such as Rwanda and Bosnia and to lesser-known conflicts in places like the Central African Republic, Namibia, and Papua New Guinea. How effective are these international interventions? Does peacekeeping work? Does it actually keep the peace in the aftermath of civil war? And if so, how? How do peacekeepers change things on the ground, from the perspective of the “peacekept,” such that war is less likely to resume? These are the questions that motivate this book. As a tool for maintaining peace, international peacekeeping was only rarely used in internal conflicts during the Cold War, but the number, size, and scope of missions deployed in the aftermath of civil wars has exploded since 1989. Early optimism about the potential of the UN and regional organizations to help settle internal conflicts after the fall of the Berlin Wall was soon tempered by the initial failure of the mission in Bosnia and the scapegoating of the UN mission in Somalia.1 The United States in particular became disillusioned with peacekeeping, objecting to anything more than a minimal international response in war-torn countries (most notoriously in Rwanda). Even in Afghanistan and Iraq, where vital interests are now at stake, the United States has been reluctant to countenance wide spread multilateral peacekeeping missions. -

Profound Forces: the Pandemic As Catalyst

the new normal in Asia A series exploring ways in which the Covid-19 pandemic might shape or reorder the world across multiple dimensions Profound Forces: The Pandemic as Catalyst Kenneth B. Pyle May 21, 2020 The eminent British historian A.J.P. Taylor often referred to the way in which “profound forces” influence the course of human history. By this, he meant that history in certain times has been changed by forces seemingly beyond the ability of humans to control. He wrote about the political and social trends that roiled Europe and led to both world wars. The profound forces seem “so overwhelming as to carry all that is before them.” If ever that was true, it is so today. We are in the thrall of driving forces. The Covid-19 pandemic is the most recent. In my view, it has acted as a kind of catalyst speeding up and intensifying the other motive forces that predated it. By distracting and further dividing nations, the pandemic has made cooperation more difficult. The cumulative effect is to create an epochal time of crisis and looming danger. The pandemic itself has a solution. A vaccine may cure it, although not the human and economic consequences. The other forces do not yet have a solution. They require collective action. Their locus is primarily in Asia, now the center of gravity in world power. Kenneth B. Pyle is the Henry M. Jackson Professor Emeritus at the University of Washington and founding president of the National Bureau of Asian Research. 1 The New Normal in Asia Together these profound forces make existential Third, there is the nuclear revolution. -

Nuclear Perils in a New Era Bringing Perspective to the Nuclear Choices Facing Russia and the United States

Nuclear Perils in a New Era Bringing Perspective to the Nuclear Choices Facing Russia and the United States Steven E. Miller and Alexey Arbatov Nuclear Perils in a New Era Bringing Perspective to the Nuclear Choices Facing Russia and the United States Steven E. Miller and Alexey Arbatov © 2021 by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences. All rights reserved. ISBN: 0-87724-139-2. This publication is available online at www.amacad.org/project/dialogue-arms-control -disarmament. Suggested citation: Steven E. Miller and Alexey Arbatov, Nuclear Perils in a New Era: Bringing Perspective to the Nuclear Choices Facing Russia and the United States (Cambridge, Mass.: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2021). Cover image: Helsinki, Finland, July 16, 2018: The national flags of Russia and the United States seen ahead of a meeting of Russia’s President Vladimir Putin and U.S. President Donald Trump. Photo by Valery Sharifulin/TASS/Getty Images. This publication is part of the American Academy’s project on Promoting Dialogue on Arms Control and Disarmament. The statements made and views expressed in this publication are those held by the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Officers and Members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Please direct inquiries to: American Academy of Arts & Sciences 136 Irving Street Cambridge, MA 02138 Telephone: 617-576-5000 Fax: 617-576-5050 Email: [email protected] Web: www.amacad.org Contents Introduction 1 The Rise and Decline of Global Nuclear Order? 3 Steven E. Miller Unmanaged Competition, -

Deterrence in the Twenty-First Century Proceedings

Deterrence in the Twenty-first Century Proceedings London, UK 18–19 May 2009 September 2010 Muir S. Fairchild Research Information Center Cataloging Data Deterrence in the twenty-first century: proceedings / [edited by Anthony C. Cain.] p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-58566-202-9 1. Deterrence (Strategy)—Congresses. 2. Security, International—Forecasting— Congresses. 3. National security—United States—Planning—Congresses. 4. Arms control—Planning—Congresses. 5. Weapons of mass destruction—Prevention— Congresses. I. Title. II. Cain, Anthony C. 355.02/17––dc22 Disclaimer The analysis, opinions, and conclusions either expressed or implied within are solely those of the au- thor and do not necessarily represent the views of the Air Force Research Institute, Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Nor do they necessarily represent the views of the Joint Services Command and Staff College, the United Kingdom Defence Academy, the United Kingdom Ministry of Defence, or any other British government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii PREFACE . vii 1 Framing Deterrence in the Twenty-first Century: Conference Summary . 1 Adam Lowther 2 Defining “Deterrence” . 15 Michael Codner 3 Understanding Deterrence . 27 Adam Lowther 4 Policy and Purpose . 41 Gen Norton A Schwartz, USAF Lt Col Timothy R. Kirk, USAF 5 Waging Deterrence in the Twenty-first Century . 63 Gen Kevin Chilton, USAF Greg Weaver 6 On Nuclear Deterrence and Assurance . 77 Keith B. Payne 7 Conference Agenda . 121 8 Contemporary Challenges for Extended Deterrence . 123 Tom Scheber 9 Case Study—The August 2008 War between Russia and Georgia . -

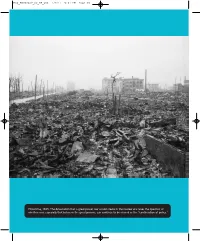

Hiroshima, 1945. the Devastation That a Great Power War Would Create In

M04_BOVA2407_00_SE_C04 1/7/11 5:01 PM Page 98 Hiroshima, 1945. The devastation that a great power war would create in the nuclear era raises the question of whether war, especially that between the great powers, can continue to be viewed as the “continuation of policy.” M04_BOVA2407_00_SE_C04 1/7/11 5:01 PM Page 99 CHAPTER 4 War and Violence in World Politics The Realist’s World Unlike breathing, eating, or sex, war is not something that is somehow required by the human condition or the forces of history. Conflicts of interest are inevitable and continue to exist within the developed world. But the notion that war should be used to resolve them has increasingly been discredited and abandoned.1 —John Mueller, 1989 The optimists’ claim that security competition and war among the great powers have been burned out of the system is wrong. In fact, all of the major states around the globe still care deeply about the balance of power and are destined to compete for power among themselves for the foreseeable future. In short, the real world remains a realist world.2 —John Mearsheimer, 2001 hroughout human history, war and the threat of war have been a constant part of international life and central to understanding how the world works. Though Tall of the international relations paradigms provide explanations for the existence and frequency of war, the structural realist view that war is rooted in international anarchy provides least cause to expect that war can ever be substantially eliminated. In a world with no effective and reliable higher authority to impose order, realists insist that states will from time to time need to protect their vital interests through the use of force and violence. -

Three Narratives of Civil War: Recurrence, Remembrance … 3

Layout: A5 HuSSci Book ID: 427254_1_En Book ISBN: 978-3-319-61179-2 Chapter No.: 1 Date: 12 August 2017 10:20 Page: 1/18 1 2 Three Narratives of Civil War: 3 Recurrence, Remembrance and Reform 4 from Sulla to Syria 5 David Armitage 6 For most of their history, from the ancient world until the nineteenth 7 century, civil wars were a subject primarily for orators, poets, historians 8 and novelists. They have been of pressing concern to lawyers for barely a 9 hundred and ffty years, for social scientists only since the 1960s and for 10 literary scholars mostly during the twenty-frst century. Civil wars have 11 accordingly been absent from social theory and from interdisciplinary 12 study more generally: there is as yet no great treatise on civil war to sit 13 alongside Clausewitz’s On War or Arendt’s On Revolution, for example.1 14 Civil War and Narrative is therefore especially welcome for joining felds 15 that have been put asunder and for bringing practitioners and scholars 16 together to examine the centrality of narratives to the experience of civil This essay has benefted from the comments of audiences in London, Berlin, New Haven and Athens. Translations are my own, unless otherwise specifed. A1 D. Armitage (*) A2 Department of History, Harvard University, Robinson Hall, A3 35 Quincy St, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA A4 e-mail: [email protected] PROOF © The Author(s) 2018 1 K. Deslandes et al. (eds.), Civil War and Narrative, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-61179-2_1 Layout: A5 HuSSci Book ID: 427254_1_En Book ISBN: 978-3-319-61179-2 Chapter No.: 1 Date: 12 August 2017 10:20 Page: 2/18 2 D. -

BOOK REVIEW ROUNDTABLE: the Revolution That Failed

BOOK REVIEW ROUNDTABLE: The Revolution that Failed June 14, 2021 Table of Contents 1. “Introduction: The Gap Between Theory and Practice,” Thomas G. Mahnken 2. “Who and What Made the Revolution that Failed?” Jayita Sarkar 3. “Nuclear Revelations About the Nuclear Revolution,” Scott D. Sagan 4. “Revolutionary Thinking: Questioning the Conventional Wisdom on Nuclear Deterrence,” Jasen J. Castillo 5. “Author Response: The Meaning of the Nuclear Counterrevolution,” Brendan Rittenhouse Green 2 Texas National Security Review 1. Introduction: The Gap Between Theory and Practice Thomas G. Mahnken Brendan Rittenhouse Green’s The Revolution that Failed: Nuclear Competition, Arms Control, and the Cold War makes an important contribution to our understanding of the history of the nuclear competition that took place between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War.1 The book calls into question the extent to which Cold War-era theories, many of which argued that the existence of a mutually assured destruction (MAD) would stabilize the Soviet- American nuclear relationship, actually influenced American policymakers in practice. Indeed, Green documents in rich detail the disconnect between the theory of MAD and the way that U.S. policymakers actually behaved between 1969 and 1979. As Green shows, American policymakers did not share theorists’ belief that the advent of nuclear weapons had transformed international relations. Nor were they convinced that the United States and Soviet Union had, by the 1970s, reached a condition of nuclear stalemate, a claim that lay at the heart of the notion of MAD. It turns out that it was far from obvious to policymakers confronted with the task of deterring the Soviet Union that nuclear deterrence was robust.2 To the contrary, most U.S. -

Foresight Into 21St Century Conflict: End of the Greatest Illusion? by Frank G

THE PHILADELPHIA PAPERS A Publication of the Foreign Policy Research Institute FORESIGHT INTO 21ST CENTURY CONFLICT: END OF THE GREATEST ILLUSION? by Frank G. Hoffman September 2016 14 FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE THE PHILADELPHIA PAPERS, NO. 14 FORESIGHT INTO 21ST CENTURY CONFLICT: END OF THE GREATEST ILLUSION? BY FRANK G. HOFFMAN SEPTEMBER 2016 www.fpri.org THE PHILADELPHIA PAPERS ABOUT THE FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE Founded in 1955 by Ambassador Robert Strausz-Hupé, FPRI is a non-partisan, non-profit organization devoted to bringing the insights of scholarship to bear on the development of policies that advance U.S. national interests. In the tradition of Strausz-Hupé, FPRI embraces history and geography to illuminate foreign policy challenges facing the United States. In 1990, FPRI established the Wachman Center, and subsequently the Butcher History Institute, to foster civic and international literacy in the community and in the classroom. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Frank G. Hoffman, Ph.D, is a Senior Research Fellow in the Center for Strategic Research, Institute for National Strategic Studies, National Defense University, Washington, DC. He also serves as a member of FPRI’s Board of Advisors. The views expressed in this Philadelphia Paper are those of the author alone, and do not represent the official policy of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. Foreign Policy Research Institute 1528 Walnut Street, Suite 610 • Philadelphia, PA 19102-3684 Tel. 215-732-3774 • Fax 215-732-4401 FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE Executive Summary This piece examines the contours of tomorrow’s security environment. It briefly examines current conflict data and then generates insights on how changes in today’s environment could alter trends in future conflicts.