Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

G-Eazy & DJ Paul Star in the Movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 in the BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED

STREET CONSEQUENCES MAGAZINE Exclusive Pull up a seat as Antonio Servidio take us through his life as a Legitimate Hustler & Executive Producer of the movie “Tunnel Vision” Featuring 90’s Bay Area Rappers Street Consequences Presents E-40, Too Short, B-Legit, Spice 1 & The New Talent of Rappers KB, Keak Da Sneak, Rappin 4-Tay Mac Fair & TRAP Q&A with T. A. Corleone Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences G-Eazy & DJ Paul star in the movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 IN THE BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED October/November 2017 2 October /November 2017 Contents Publisher’s Word Exclusive Interview with Antonio Servidio Featuring the Bay Area Rappers Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences Street Consequences presents new talent of Rappers October/November 2017 3 Publisher’s Words Street Consequences What are the Street Consequences of today’s hustling life- style’s ? Do you know? Do you have any idea? Street Con- sequences Magazine is just what you need. As you read federal inmates whose stories should give you knowledge on just what the street Consequences are. Some of the arti- cles in this magazine are from real people who are in jail because of these Street Consequences. You will also read their opinion on politics and their beliefs on what we, as people, need to do to chance and make a better future for the up-coming youth of today. Stories in this magazine are from big timer in the games to small street level drug dealers and regular people too, Hopefully this magazine will open up your eyes and ears to the things that are going on around you, and have to make a decision that will make you not enter into the game that will leave you dead or in jail. -

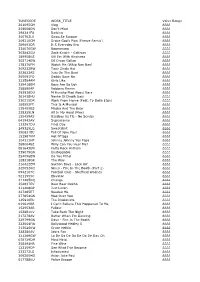

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Pdf, 328.17 KB

00:00:00 Music Music Gentle, trilling music with a steady drumbeat plays under the dialogue. 00:00:01 Promo Promo Speaker: Bullseye with Jesse Thorn is a production of MaximumFun.org and is distributed by NPR. [Music fades out.] 00:00:12 Jesse Host I’m Jesse Thorn. It’s Bullseye. Thorn 00:00:14 Music Music “Huddle Formation” from the album Thunder, Lightning, Strike by The Go! Team plays. A fast, upbeat, peppy song. Music plays as Jesse speaks, then fades out. 00:00:21 Jesse Host It’s a cliché, but it’s also true: Randy Newman doesn’t really need an introduction. [Music begins to fade out to be replaced with “You’ve Got a Friend in Me”.] I mean, I can say Randy Newman to you and you’ll probably start thinking about this. 00:00:31 Music Music “You’ve Got a Friend in Me” by Randy Newman from the movie Toy Story. Sweet, gentle music. You’ve got a friend in me You’ve got a friend in me When the road looks rough ahead And you’re miles and miles… [Music fades into “Short People”] 00:00:44 Jesse Host Or this. 00:00:45 Music Music “Short People” by Randy Newman. Upbeat, fun music. Short people got no reason Short people got no reason Short people got no reason To live… [Music fades into “I Love L.A.”] 00:01:00 Jesse Host Or maybe this. 00:01:02 Music Music “I Love L.A.” by Randy Newman. I love L.A. -

A Phenomenological Research Study on the Treatment

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NSU Works Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks Department of Conflict Resolution Studies Theses CAHSS Theses and Dissertations and Dissertations 1-1-2018 A Phenomenological Research Study on the Treatment Experience of Opioid Addicts: Exploring the Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Conflicts that Opioid Addicts Face During the Treatment Process Nicole Marie Ouzounian This document is a product of extensive research conducted at the Nova Southeastern University College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences. For more information on research and degree programs at the NSU College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences, please click here. Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/shss_dcar_etd Part of the Community-Based Research Commons, and the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Share Feedback About This Item This Dissertation is brought to you by the CAHSS Theses and Dissertations at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Conflict Resolution Studies Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Phenomenological Research Study on the Treatment Experience of Opioid Addicts: Exploring the Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Conflicts that Opioid Addicts Face During the Treatment Process by Nicole Ouzounian A Dissertation Presented to the College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences of Nova Southeastern University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Nova Southeastern University 2018 Nova Southeastern University College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences This dissertation was submitted by Nicole Ouzounian under the direction of the chair of the dissertation committee listed below. -

The Deaf Movement and Musical Theater

The Deaf Movement and Musical Theater [00:00:05] Welcome to The Seattle Public Library’s podcasts of author readings and library events. Library podcasts are brought to you by The Seattle Public Library and Foundation. To learn more about our programs and podcasts, visit our web site at w w w dot SPL dot org. To learn how you can help the library foundation support The Seattle Public Library go to foundation dot SPL dot org [00:00:36] Welcome everyone. My name is Bob Tang the music librarian here at Seattle Public Library. And I want to thank you all for coming to this presentation Cole presentation with the library with Fifth Avenue theater for their production of The Hunchback of Notre Dame. And without any further ado I'd like to welcome Orlando and Josh and E.J.. Hello. Hello. Mr.. Safe behind these windows and still. Gazing at the people down. On. My life as I write I'm hungry for the mysteries all my life I memorized things [00:01:31] Knowing Penn State will never know. [00:01:35] All my life I will wonder how it feels to the last day. Not above [00:01:52] Saying hey this is what I do. Just say [00:02:37] We send their wives through the roofs and see every day they shout scolding go about their life. [00:02:46] Keep this up they keep telling us to be bad. Or. Since [00:04:00] So my name is Orlando Miralis I am the Director of Education and Engagement at the Fifth Avenue theater. -

G-Eazy Firar Albumreleasen Av ”When It's Dark Out”

2015-11-16 15:35 CET G-Eazy firar albumreleasen av ”When It’s Dark Out” med Sverigebesök I samband med albumreleasen av ”When It’s Dark Out” som släpps den 4 december kommer den amerikanske rapparen G-Eazy till Sverige den 26 november för att göra en exklusiv spelning i Stockholm. G-Eazy är just nu aktuell med singeln ”Me, Myself & I” feat. Bebe Rexha som är producerad av Michael Keenan. G-Eazy vars riktiga namn är Gerald Earl Gillum har tillsammans med parhästen Christoph Anderson samt Boi-1da, Southside, DJ Spinz, Kane Beatz och Remo producerat det nya albumet. ”When It’s Dark Out” är uppföljaren till albumet “These Things Happen” som gick rakt in på förstaplatsen på Billboard R&B/Hip-Hop-listan och albumlistan Top Rap. ”These Things Happen” säkrade även en tredjeplats på den prestigefulla topplistan Billboard 200. Det hyllade debutalbumet gästades av artister som E-40, A$AP Ferg, Jay Ant, Blackbear och innehöll framgångsrika låtar som “Far Alone”, “Let’s Get Lost”, “I Mean It”, ”Tumblr Girls” och “Lotta That”. ”These Things Happen” fick två miljoner streams på Spotify i USA under releaseveckan och blev därmed ett av de starkaste debutalbumen i USA under 2014. G-Eazys musik och liveframträdanden har hyllats av bland annat Billboard, MTV, Interview Magazine, Pitchfork, VIBE, The Source, Rolling Stone Magazine och The New York Times. Efter 40 000 sålda biljetter under en utsåld världsturné och framträdanden på festivaler så som Roskilde, Wireless och Lollapalooza är vi extra stolta och glada att G-Eazy kommer till Stockholm för en exklusiv spelning samt för att möta svensk media för första gången. -

Riaa Gold & Platinum Awards

1/1/2016 — 2/29/2016 In January and February 2016, RIAA certified158 Digital Single Awards and 74 Album Awards. Complete lists of all RIAA Gold & Platinum Awards dating all the way back to 1958 are available at the newly redesigned riaa.com. RIAA GOLD & JAN. & FEB. 2016 PLATINUM AWARDS DIGITAL MULTI-PLATINUM SINGLE (46) Cert Date Title Artist Label Plat Level Rel. Date 2/8/2016 AMNESIA 5 SECONDS OF CAPITOL RECORDS 2 7/1/2014 SUMMER 1/25/2016 HELLO ADELE COLUMBIA/XL RECORDINGS 6 10/23/2015 1/25/2016 HELLO ADELE COLUMBIA/XL RECORDINGS 5 10/23/2015 1/7/2016 HERE ALESSIA CARA DEF JAM 2 5/1/2015 1/26/2016 LOVE ME HARDER ARIANA GRANDE REPUBLIC RECORDS 3 8/25/2014 1/26/2016 LOVE ME HARDER ARIANA GRANDE REPUBLIC RECORDS 2 8/25/2014 1/26/2016 HOTLINE BLING DRAKE YOUNG MONEY/CASH 5 7/31/2015 MONEY/REPUBLIC RECORDS 2/29/2016 THINKING OUT LOUD ED SHEERAN ATLANTIC RECORDS 6 9/24/2014 2/29/2016 PHOTOGRAPH ED SHEERAN ATLANTIC RECORDS 2 5/11/2015 1/28/2016 STAY FLORIDA GEORGIA BMX 2 12/4/2012 LINE 1/29/2016 BURNIN’ IT DOWN JASON ALDEAN BROKEN BOW 2 7/22/2014 2/1/2016 SHE’S COUNTRY JASON ALDEAN BROKEN BOW 3 12/1/2008 2/15/2016 BIRTHDAY SEX JEREMIH DEF JAM 2 6/30/2009 1/15/2016 WHAT DO YOU MEAN JUSTIN BIEBER DEF JAM RECORDS 3 8/28/2015 1/15/2016 WHAT DO YOU MEAN JUSTIN BIEBER DEF JAM RECORDS 4 8/28/2015 1/15/2016 SORRY JUSTIN BIEBER DEF JAM 3 10/28/2015 1/15/2016 LOVE YOURSELF JUSTIN BIEBER DEF JAM 2 11/13/2015 www.riaa.com GoldandPlatinum @RIAA @riaa_awards JAN. -

Calling out Culture Vultures: Nonwhite Interpretations of Cultural Appropriation in the Era of Colorblindness

Calling Out Culture Vultures: Nonwhite Interpretations of Cultural Appropriation in the Era of Colorblindness A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School at the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Sociology of the College of Arts and Sciences by Aaryn L. Green B.A., University of Cincinnati, 2009 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 2012 Dissertation Chair: Erynn Casanova Committee Members: Jennifer Malat Annulla Linders June 2018 Abstract Colorblind theory argues that racism has not subsided but has taken on a new form which appears nonracial and is hard to detect. Music videos are one form of popular culture that utilizes cross-racial or cultural images which appear to be racially inclusive, but when closely analyzed are firmly rooted in traditional stereotypes and take cultural expressions out of their proper sociohistorical contexts. This process is called cultural appropriation. Too often, researchers have determined what modes of appropriation are or are not harmful to various groups without any input from those groups. In this study I provide a space for racial groups whose creations or expressions are habitually appropriated to tell us which modes of appropriation they consider to be harmful. I use a dual qualitative method—music video content analysis and focus group interviews with 61 participants—to investigate representations of nonwhite cultures and how audiences of color interpret the use of their cultures within popular music -

Journal of Hip Hop Studies

et al.: Journal of Hip Hop Studies June 2016 Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2016 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 3 [2016], Iss. 1, Art. 1 Editor in Chief: Daniel White Hodge, North Park University Senior Editorial Advisory Board: Anthony Pinn, Rice University James Paterson, Lehigh University Book Review Editor: Gabriel B. Tait, Arkansas State University Associate Editors: Cassandra Chaney, Louisiana State University Jeffrey L. Coleman, St. Mary’s College of Maryland Monica Miller, Lehigh University Associate & Copy Editor: Travis Harris, PhD Student, College of William and Mary Editorial Board: Dr. Rachelle Ankney, North Park University Dr. Jason J. Campbell, Nova Southeastern University Dr. Jim Dekker, Cornerstone University Ms. Martha Diaz, New York University Mr. Earle Fisher, Rhodes College/Abyssinian Baptist Church, United States Dr. Daymond Glenn, Warner Pacific College Dr. Deshonna Collier-Goubil, Biola University Dr. Kamasi Hill, Interdenominational Theological Center Dr. Andre E. Johnson, University of Memphis Dr. David Leonard, Washington State University Dr. Terry Lindsay, North Park University Ms. Velda Love, North Park University Dr. Anthony J. Nocella II, Hamline University Dr. Priya Parmar, SUNY Brooklyn, New York Dr. Soong-Chan Rah, North Park University Dr. Rupert Simms, North Park University Dr. Darron Smith, University of Tennessee Health Science Center Dr. Jules Thompson, University Minnesota, Twin Cities Dr. Mary Trujillo, North Park University Dr. Edgar Tyson, Fordham University Dr. Ebony A. Utley, California State University Long Beach, United States Dr. Don C. Sawyer III, Quinnipiac University https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jhhs/vol3/iss1/1 2 et al.: Journal of Hip Hop Studies . Sponsored By: North Park Universities Center for Youth Ministry Studies (http://www.northpark.edu/Centers/Center-for-Youth-Ministry-Studies) Save The Kids Foundation (http://savethekidsgroup.org/) Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2016 3 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. -

Zaki Syed Masters Thesis the Final One.Pdf

THE EFFECT OF UNDERGROUND RAP ON RAPPERS INDENTITIES A Thesis Presented to Faculty of the Department of Sociology California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Sociology by Zaki Syed FALL 2013 © 2013 Zaki Syed ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii THE EFFECT OF UNDERGROUND RAP ON RAPPERS IDENTITIES A Thesis by Zaki Syed Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Cid Martinez, PhD. __________________________________, Second Reader Ayad Al Qazzaz, PhD. ____________________________ Date iii Student: Zaki Syed I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. _______________________, Graduate Coordinator ___________________ Amy Liu, PhD. Date Department of Sociology iv Abstract of THE EFFECT OF UNDERGROUND RAP ON RAPPERS IDENTITIES by Zaki Syed Rap and hip-hop provide a forum for marginalized populations to express and create their own unique identity. To further understand rap and the concept of identity, two local hip-hop groups were examined and observed for a period of three months. One of two hip-hop groups represented consisted of members that resided in the inner city and were practicing Muslims. While, the other group consisted of Caucasian middle class youth. Though they differed drastically, both groups to a certain extent were marginalized from their surrounding communities. To help guide the research sociological theories from two prominent sociologists, Randall Collins and W.E. B. Dubois, were employed. Randall Collin’s theory of Interactional Ritual Chains helped to define how the rappers developed group identity and solidarity through group rituals. -

![Inside the Studio [Entire Talk]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3948/inside-the-studio-entire-talk-6443948.webp)

Inside the Studio [Entire Talk]

Stanford eCorner Inside the Studio [Entire Talk] Sam Seidel, Hasso Plattner Institute of Design 12-06-2019 URL: https://ecorner.stanford.edu/video/inside-the-studio-entire-talk/ From developing a brand identity to cultivating the right conditions for musical exploration, successful recording artists are masters of the creative process. Hosted by Stanford professor Bob Sutton, Sickamore, a hip-hop artist, photographer and the creative director at Interscope Records, joins Sam Seidel, director of K-12 strategy and research at Stanford’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design, for an intimate conversation about what entrepreneurs can learn from the music industry, how to navigate ambiguity, and why it’s important to strike the right balance between open-ended creativity and project completion. Transcript - [Announcer] Who you are defines how you build.. - Sickamore and I both come from hip hop culture and in hip hop culture we place a premium on freshness.. Right? Like, somebody could say a rhyme one day and it's incredible and it blows everyone's minds and then if someone else comes and says the same rhyme the next day and thinks they're gonna get the same reaction and everyone's like, that's whack, I heard somebody else already say that, like I'm not impressed.. Same with graffiti.. Same with dance moves.. It's like the premium has always been on innovation in hip hip culture and there's also often a competitive spirit to it.. So, I've studied every interview that you've done at Harvard, at UCLA, Rap Radar, and my goal is to be fresher (audience laughs) and get all new content, all new stories, like ask different questions and just make it a whole new thing. -

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When