Card-Pitt: the Carpits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF of This Issue

MITF's vThe Weather Oldest and Largest Today: Cloudy, showers, 45°F (7°C) Newspaper :, Tonight: Fog, showers, 35°F (I°C) . 2 _ Tomorrow: Cool, showers, 42°F (6°C) Details Page 2 VolurnV-olume e !II3,Number 13, Number 177 . Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Friday, Aprilt2, 1993 ~~. Cabrdg,. .... Mascuetacustt .23 0l3. .f... ,_..... .. .... Friday, April 2, 1993 I~~~- _ . ._ | . AEPhi Could Come to MIT City Proposes Parking Changes By Nicole A. Sherry By Aaron Bel:enky eating the parking spaces. The meet- residents and commuters alike, Pre- STAFF REPORTER ADVER SING MANAGER ing was attended by about 25 mem- ston said. Nine undergraduate women hoping to bring a new sorority, Alpha On Tuesday evening, the City of bers of the MIT community, mostly In 1992, the policy was changed Epsilon Phi, to MIT made a presentation to the Panhellenic Associa- Cambridge held a meeting with students with cars who are upset by to allow a limited number of addi- tion Wednesday night. They are awaiting a decision as to whether a MIT students and staff to discuss the current parking situation and tional parking spaces to be allocat- fifth sorority will be invited to come onto campus. drastic changes to on-street parking even more disturbed by the pro- ed. Under the existing plan, for On Wednesday night, the nine women as well as representatives proposed by the city. posed changes. every two unrestricted parking from the national AEPhi organization made a presentation to mem- The meeting focused on the The negative reaction prompted spaces that are converted to some bers of the four existing sororities. -

Remember the Cleveland Rams?

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 7, No. 4 (1985) Remember the Cleveland Rams? By Hal Lebovitz (from the Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 20, 1980) PROLOGUE – Dan Coughlin, our bubbling ex-baseball writer, was saying the other day, “The Rams are in the Super Bowl and I’ll bet Cleveland fans don’t even know the team started right here.” He said he knows about the origin of the Rams only because he saw it mentioned in a book. Dan is 41. He says he remembers nothing about the Rams’ days in Cleveland. “Probably nobody from my generation knows. I’d like to read about the team, how it came to be, how it did, why it was transferred to Los Angeles. I’ll bet everybody in town would. You ought to write it.” Dan talked me into it. What follows is the story of the Cleveland Rams. If it bores you, blame Coughlin. * * * * Homer Marshman, a long-time Cleveland attorney, is the real father of the Rams. He is now 81, semi- retired, winters in his home on gold-lined Worth Avenue in Palm Beach, Fla., runs the annual American Cenrec Society Drive there. His name is still linked to a recognized law firm here – Marshman, Snyder and Corrigan – and he owns the Painesville harness meet that runs at Northfield each year. The team was born in 1936 in exclusive Waite Hill, a suburb east of Cleveland. Marshman vividly recalls his plunge into pro football. “A friend of mine, Paul Thurlow, who owned the Boston Shamrocks, called me. He said a new football league was being formed. -

Eagles' Team Travel

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2019-2020 EDITIOn PHILADELPHIA EAGLES Team History The Eagles have been a Philadelphia institution since their beginning in 1933 when a syndicate headed by the late Bert Bell and Lud Wray purchased the former Frankford Yellowjackets franchise for $2,500. In 1941, a unique swap took place between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh that saw the clubs trade home cities with Alexis Thompson becoming the Eagles owner. In 1943, the Philadelphia and Pittsburgh franchises combined for one season due to the manpower shortage created by World War II. The team was called both Phil-Pitt and the Steagles. Greasy Neale of the Eagles and Walt Kiesling of the Steelers were co-coaches and the team finished 5-4-1. Counting the 1943 season, Neale coached the Eagles for 10 seasons and he led them to their first significant successes in the NFL. Paced by such future Pro Football Hall of Fame members as running back Steve Van Buren, center-linebacker Alex Wojciechowicz, end Pete Pihos and beginning in 1949, center-linebacker Chuck Bednarik, the Eagles dominated the league for six seasons. They finished second in the NFL Eastern division in 1944, 1945 and 1946, won the division title in 1947 and then scored successive shutout victories in the 1948 and 1949 championship games. A rash of injuries ended Philadelphia’s era of domination and, by 1958, the Eagles had fallen to last place in their division. That year, however, saw the start of a rebuilding program by a new coach, Buck Shaw, and the addition of quarterback Norm Van Brocklin in a trade with the Los Angeles Rams. -

These Savvy Subitizing Cards Were Designed to Play a Card Game I Call Savvy Subitizing (Modeled After the Game Ratuki®)

********Advice for Printing******** You can print these on cardstock and then cut the cards out. However, the format was designed to fit on the Blank Playing Cards with Pattern Backs from http://plaincards.com. The pages come perforated so that once you print, all you have to do is tear them out. Plus, they are playing card size, which makes them easy to shufe and play with.! The educators at Mathematically Minded, LLC, believe that in order to build a child’s mathematical mind, connections must be built that help show children that mathematics is logical and not magical. Building a child’s number sense helps them see the logic in numbers. We encourage you to use !these cards in ways that build children’s sense of numbers in four areas (Van de Walle, 2013):! 1) Spatial relationships: recognizing how many without counting by seeing a visual pattern.! 2) One and two more, one and two less: this is not the ability to count on two or count back two, but instead knowing which numbers are one and two less or more than any given number.! 3) Benchmarks of 5 and 10: ten plays such an important role in our number system (and two fives make a 10), students must know how numbers relate to 5 and 10.! 4) Part-Part-Whole: seeing a number as being made up of two or more parts.! These Savvy Subitizing cards were designed to play a card game I call Savvy Subitizing (modeled after the game Ratuki®). Printing this whole document actually gives you two decks of cards. -

GEORGETOWN FOOTBALL GAME NOTES @Hoyasfb @Georgetownhoyas

2019 GEORGETOWN FOOTBALL GAME NOTES @HoyasFB @GeorgetownHoyas @hoyafootball @GeorgetownAthletics 2019 FOOTBALL GAME NOTES /Georgetown Football FOOTBALL CONTACT: BRENDAN THOMAS /Georgetown Athletics [email protected] | 202-687-6783 (O) | 207-400-2840 (C) | WWW.GUHOYAS.COM 2018 SCHEDULE GAME 1: GEORGETOWN (0-0, 0-0 PATRIOT LEAGUE) Date Opponent Time / Result AT DAVIDSON (0-0, 0-0 PIONEER FOOTBALL LEAGUE) KICKOFF – SATURDAY, AUGUST 31, 2019 (1 P.M. ET) Aug. 31 at Davidson 1 p.m. LOCATION – RICHARDSON STADIUM (DAVIDSON, N.C.) SEPT. 7 MARIST 12:30 P.M. LIVE STATS: GUHOYAS.COM | VIDEO: GUHOYAS.COM SEPT. 14 CATHOLIC NOON TALENT: SAM HYMAN (PXP); COREY HODGES (ANALYST) Sept. 28 at Columbia 1 p.m. Oct. 5 at Cornell 3 p.m. SERIES INFO FIRST MEETING: LAST FIVE MEETINGS: OCT. 12 FORDHAM * (HOMECOMING) 2 P.M. Overall Record ............. 9-3 10/16/1999 (H; L, 28-27) Result Rec. OCT. 19 LAFAYETTE * NOON Home ............................ 5-2 LAST MEETING: 9/3/2016 H W, 38-14 9-3 Oct. 26 at Lehigh * 12:30 p.m. Away ............................ 4-1 9/3/2016 (H; W, 38-14) 9/7/2013 H W, 42-6 8-3 NOV. 2 COLGATE * (SENIOR DAY) NOON Neutral ........................N/A LAST GU WIN: 9/1/2012 A W, 35-14 7-3 Nov. 16 at Bucknell * 1 p.m. Streak ...........................W5 9/3/2016 (H; W, 38-14) 9/3/2011 H W, 40-16 6-3 Nov. 23 at Holy Cross * Noon 9/4/2010 A W, 20-10 5-3 GAME DAY NOTES The Georgetown University football team opens the 2019 season at Davidson on Saturday, the sixth season with Head home games in BOLD CAPS played at Cooper Field Coach Rob Sgarlata at the helm. -

Marshall Goldberg

Professional Football Researchers Association www.profootballresearchers.com Marshall Goldberg This article was written by Matt Keddie. Marshall Goldberg was always a big dreamer. It was not ironic during his playing days that he earned the nickname, “Biggie”.1 No matter the sport he played or the team he played on, Marshall fit right in with his natural athletic ability. He ascended through the football ranks to star with the NFL's Chicago Cardinals as a fabulous two-way player in the 1940s. His eight year NFL career from 1939 to 1948 was briefly interrupted by a short stint due to service in the US Navy (1944, 1945). During his career, he was arguably the Cardinals' best player, and a top back during the war time era. Marshall was born to Sol Goldberg and Rebecca Fram in Elkins, West Virginia on October 24, 1917. Both immigrants, his parents worked as entrepreneurs in the clothing business.23 They worked hard for what they had, and saved all they could. As a result, Marshall's home life was very blue-collar. He learned the values of working for everything – the food he ate, the clothes on his back, and the success he would achieve in life. Among his interests growing up: competitive sports. He stood roughly 5'11” and 190 pounds, an athletic build that allowed him to star at Elkins High School on the football, track, and basketball teams. Goldberg was not only the team captain, but he was also an All-State performer in his senior year.4 Marshall's astounding success drew the interest of major college football powerhouses from across the country. -

Major League Baseball in Nineteenth–Century St. Louis

Before They Were Cardinals: Major League Baseball in Nineteenth–Century St. Louis Jon David Cash University of Missouri Press Before They Were Cardinals SportsandAmerican CultureSeries BruceClayton,Editor Before They Were Cardinals Major League Baseball in Nineteenth-Century St. Louis Jon David Cash University of Missouri Press Columbia and London Copyright © 2002 by The Curators of the University of Missouri University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201 Printed and bound in the United States of America All rights reserved 54321 0605040302 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cash, Jon David. Before they were cardinals : major league baseball in nineteenth-century St. Louis. p. cm.—(Sports and American culture series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8262-1401-0 (alk. paper) 1. Baseball—Missouri—Saint Louis—History—19th century. I. Title: Major league baseball in nineteenth-century St. Louis. II. Title. III. Series. GV863.M82 S253 2002 796.357'09778'669034—dc21 2002024568 ⅜ϱ ™ This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984. Designer: Jennifer Cropp Typesetter: Bookcomp, Inc. Printer and binder: Thomson-Shore, Inc. Typeface: Adobe Caslon This book is dedicated to my family and friends who helped to make it a reality This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix Prologue: Fall Festival xi Introduction: Take Me Out to the Nineteenth-Century Ball Game 1 Part I The Rise and Fall of Major League Baseball in St. Louis, 1875–1877 1. St. Louis versus Chicago 9 2. “Champions of the West” 26 3. The Collapse of the Original Brown Stockings 38 Part II The Resurrection of Major League Baseball in St. -

This Is Not a Dissertation: (Neo)Neo-Bohemian Connections Walter Gainor Moore Purdue University

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2015 This Is Not A Dissertation: (Neo)Neo-Bohemian Connections Walter Gainor Moore Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations Recommended Citation Moore, Walter Gainor, "This Is Not A Dissertation: (Neo)Neo-Bohemian Connections" (2015). Open Access Dissertations. 1421. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/1421 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Graduate School Form 30 Updated 1/15/2015 PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Walter Gainor Moore Entitled THIS IS NOT A DISSERTATION. (NEO)NEO-BOHEMIAN CONNECTIONS For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Is approved by the final examining committee: Lance A. Duerfahrd Chair Daniel Morris P. Ryan Schneider Rachel L. Einwohner To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Thesis/Dissertation Agreement, Publication Delay, and Certification Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 32), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy of Integrity in Research” and the use of copyright material. Approved by Major Professor(s): Lance A. Duerfahrd Approved by: Aryvon Fouche 9/19/2015 Head of the Departmental Graduate Program Date THIS IS NOT A DISSERTATION. (NEO)NEO-BOHEMIAN CONNECTIONS A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Walter Moore In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Lance, my advisor for this dissertation, for challenging me to do better; to work better—to be a stronger student. -

A Preliminary Container List

News and Communications Services Photographs (P 57) Subgroup 1 - Individually Numbered Images Inventory 1-11 [No images with these numbers.] 12 Kidder Hall, ca. 1965. 13-32 [No images with these numbers.] 33 McCulloch Peak Meteorological Research Station; 2 prints. Aerial view of McCulloch Peak Research Center in foreground with OSU and Corvallis to the southeast beyond Oak Creek valley and forested ridge; aerial view of OSU in foreground with McCulloch Peak to the northwest, highest ridge top near upper left-hand corner. 34-97 [No images with these numbers.] 98-104 Music and Band 98 3 majorettes, 1950-51 99 OSC Orchestra 100 Dick Dagget, Pharmacy senior, lines up his Phi Kappa Psi boys for a quick run-through of “Stairway to the Stars.” 101 Orchestra with ROTC band 102 Eloise Groves, Education senior, leads part of the “heavenly choir” in a spiritual in the Marc Connelly prize-winning play “Green Pastures,” while “de Lawd” Jerry Smith looks on approvingly. 103 The Junior Girls of the first Christian Church, Corvallis. Pat Powell, director, is at the organ console. Pat is a senior in Education. 104 It was not so long ago that the ambitious American student thought he needed a European background to round off his training. Here we have the reverse. With Prof. Sites at the piano, Rudolph Hehenberger, Munich-born German citizen in the country for a year on a scholarship administered by the U.S. Department of State, leads the OSC Men’s Glee Club. 105-106 Registrar 105 Boy reaching into graduation cap, girl holding it, 1951 106 Boys in line 107-117 Forest Products Laboratory: 107-115 Shots of people and machinery, unidentified 108-109 Duplicates, 1950 112 14 men in suits, 1949 115 Duplicates 116 Charles R. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. IDgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & HoweU Information Compaiy 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 OUTSIDE THE LINES: THE AFRICAN AMERICAN STRUGGLE TO PARTICIPATE IN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL, 1904-1962 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State U niversity By Charles Kenyatta Ross, B.A., M.A. -

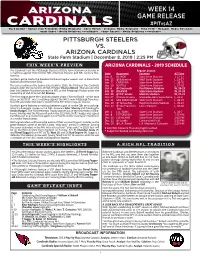

Game Release

WEEK 14 GAME RELEASE #PITvsAZ Mark Dal ton - Senior Vice Presid ent, Med ia Re l ations Ch ris Mel vin - Director, Med i a Rel ations Mik e He l m - Manag e r, Me d ia Rel ations I mani Sub e r - Me dia R e latio n s Coo rdinato r C hase Russe l l - M e dia Re latio ns Coor dinat or PITTSBURGH STEELERS VS. ARIZONA CARDINALS State Farm Stadium | December 8, 2019 | 2:25 PM THIS WEEK’S PREVIEW ARIZONA CARDINALS - 2019 SCHEDULE The Cardinals host the Pi sburgh Steelers at State Farm Stadium on Sunday in Regular Season a matchup against their former NFL American Division and NFL Century Divi- Date Opponent Loca on AZ Time sion foe. Sep. 8 DETROIT State Farm Stadium T, 27-27 Sunday's game marks the Steelers third-ever regular season visit to State Farm Sep. 15 @ Bal more M&T Bank Stadium L, 23-17 Stadium and fi rst since 2011. Sep. 22 CAROLINA State Farm Stadium L, 38-20 The series between the teams dates back to 1933, the fi rst year the Cardinals Sep. 29 SEATTLE State Farm Stadium L, 27-10 played under the ownership of Hall of Famer Charles Bidwill. That was also the Oct. 6 @ Cincinna Paul Brown Stadium W, 26-23 year the Steelers franchise joined the NFL as the Pi sburgh Pirates under the Oct. 13 ATLANTA State Farm Stadium W, 34-33 ownership of Hall of Famer Art Rooney. Oct. 20 @ N.Y. Giants MetLife Stadium W, 27-21 The fi rst league game the Cardinals played under Charles Bidwill - which took Oct. -

1938 DUKE FOOTBALL Clarkston Hines for a 97-Yard Touch- Unbeaten G Untied G Unscored Upon Down to Establish Duke’S Longest Play from Scrimmage

TRADITION G PAGE 164 TRADITION G PAGE 165 DUKE FOOTBALL TIMELINE Wallace Wade Jerry Barger November 29, 1888 November 16, 1935 1940 NFL Draft November 19, 1949 Trinity College, which would become Duke’s Jack Alexander rushes for 193 Duke’s George McAfee becomes the The crowd of 57,500, Duke’s largest to Duke University in 1924, defeats the yards as the Blue Devils post a 25-0 second overall pick in the draft and is date, pour into what is now Wallace University of North Carolina, 16-0, in victory over North Carolina ... Duke selected by the Philadelphia Eagles ... Wade Stadium to see Duke lose to the fi rst game of college football played fi nished the year with an 8-2 ledger. Tennessee’s George Cafego, chosen by North Carolina in a hard-fought 21-20 below the Mason-Dixon line. the Cardinals, is the top pick. decision. October 10, 1936 November 14, 1891 Duke defeats Clemson, 25-0, in the third 1941 Season November 4, 1950 The Trinity College football team de- and fi nal meeting between ledgendary Over the course of the season, Duke In the last of fi ve coaching battles feats Furman 96-0 ... The 1891 sqaud head coaches Wallace Wade and Jess manages to outscore its opponents by between legendary coaches Wallace went on to an undefeated 3-0 record Neely ... The Blue Devils won all three an astounding 266 points en route to its Wade of Duke and Bobby Dodd of that year, also posting wins over North showdowns. second appearance in the Rose Bowl ..