Remember the Cleveland Rams?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Cleveland Heights Tigers Football Roster

THREE OHSAA FOOTBALL PLAYOFF APPEARANCES (2011, 2013, and 2015) CLEVELAND HEIGHTS 2019 TIGERS FOOTBALL GAME NOTES 2019 Schedule & Results Gameday Storylines Game #9 • Friday, October 25, 2019 • Cleveland Heights Stadium • 7:00 PM kickoff MEDINA BEES L 10-21 Friday, August 30 Ken Dukes Stadium Shaw 2-6 overall 0-3 LEL GLENVILLE TARBLOODERS W 17-0 CARDINALS Friday, September 6 Cleveland Heights High School Stadium Cleveland Heights 7-1 overall SHAKER HTS RED RAIDERS W 50-6 Saturday, September 14 TIGERS 3-0 LEL Russell H. Rupp Field Last Meeting between Cleveland Heights and Shaw: LAKE CATHOLIC COUGARS W 28-23 October 19, 2018 (week 9); Cleveland Heights 17, Shaw 8 Friday, September 20 Jerome T. Osborne Stadium Cleveland Heights Tigers in Week 9 games since 2000 Week 9 has been one of the most successful week's of the season for the Tigers over the past two decades. Since WALSH JESUIT WARRIORS W 38-30 2000, the Tigers are 12-7 overall in Week 9 games, having won 4 in a row, 5 of their last 6 and 8 of their last 10 Friday, September 27 games played in Week 10. The Tigers current four-game winning stream in Week 9, includes three consecutive Cleveland Heights High School Stadium wins over the Shaw Cardinals LORAIN TITANS W 35-28 Friday, October 4 George Daniel Field Opening Drive BEDFORD BEARCATS W 39-6 Cleveland Heights puts a 7-game winning streak on the line when the Tigers host Friday, October 11 Cleveland Heights High School Stadium the Shaw Cardinals for an LEL matchup in Week 9. -

Bee Gee News August 6, 1947

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 8-6-1947 Bee Gee News August 6, 1947 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "Bee Gee News August 6, 1947" (1947). BG News (Student Newspaper). 826. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/826 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. O'HH •<>!• ( "- N LIBRARY All IJM News that. Wc Print Bee Qee ^IIMOTIII ,0**- Official Stad«l PubJtcatWn M BuwS»g Green State OalTenrrr VOLUME XXXI BOWLING GREEN, OHIO, WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 6, 1947 NUMBER 11 Speech Department Enrollment Record Adds Graduate Work Predicted For Fall Dr. C. H. Wesley Speaks To Fall Curriculum Four thousand to 4,200 students are expected to set an all-time en- At Commencement Friday A graduate program has been rollment record this fall, John W. established for next year which Bunn, registrar, said this week. Dr. Charles H. Wesley, president of the state-sponsored will result in changes in the cur- The previous high for the Uni- College of Education and Industrial Arts at Wilberforce Uni- riculum of the speech department. versity was 3,9,18. versity, will be the Commencement speaker for the summer- term graduation to be held Friday, Aug. -

Bill Willis: Dominant Defender

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 16, No. 5 (1994) BILL WILLIS: DOMINANT DEFENDER By Bob Carroll Bill Willis was one of the most dominant defensive linemen to play pro football after World War II. His success helped open the doors of the pro game for other Afro-Americans. William K. Willis was born October 5, 1921 in Columbus, Ohio, the son of Clement and Willana Willis. His father died when he was four, and he was raised by his grandfather and mother. He attended Columbus East High School and at first was more interested in track than football. "I had a brother, Claude, who was about six years older than me," Willis says. "He was an outstanding football player, a fullback in high school and I was afraid I would be compared with him." When he finally went out for football, he chose to play in the line despite the great speed that seemingly destined him for the backfield. He was a three-year regular at Columbus East, winning Honorable Mention All-State honors in his senior year. After working a year, Willis entered Ohio State University in 1941 and quickly caught the eye of Coach Paul Brown. At 6-2 but only 202 pounds, he was small for a tackle on a major college team, but his quickness made him a regular as a sophomore. At season's end, the 9-1 Buckeyes won the 1942 Western Conference (Big 10) championship and were voted the number one college team in the country by the Associated Press. Wartime call-ups hurt the team in Willis' final two years as most of OSU's experienced players as well as Coach Brown went into the service, but his own reputation continued to grow. -

Castrovince | October 23Rd, 2016 CLEVELAND -- the Baseball Season Ends with Someone Else Celebrating

C's the day before: Chicago, Cleveland ready By Anthony Castrovince / MLB.com | @castrovince | October 23rd, 2016 CLEVELAND -- The baseball season ends with someone else celebrating. That's just how it is for fans of the Indians and Cubs. And then winter begins, and, to paraphrase the great meteorologist Phil Connors from "Groundhog Day," it is cold, it is gray and it lasts the rest of your life. The city of Cleveland has had 68 of those salt-spreading, ice-chopping, snow-shoveling winters between Tribe titles, while Chicagoans with an affinity for the North Siders have all been biding their time in the wintry winds since, in all probability, well before birth. Remarkably, it's been 108 years since the Cubs were last on top of the baseball world. So if patience is a virtue, the Cubs and Tribe are as virtuous as they come. And the 2016 World Series that arrives with Monday's Media Day - - the pinch-us, we're-really-here appetizer to Tuesday's intensely anticipated Game 1 at Progressive Field -- is one pitting fan bases of shared circumstances and sentiments against each other. These are two cities, separated by just 350 miles, on the Great Lakes with no great shakes in the realm of baseball background, and that has instilled in their people a common and eventually unmet refrain of "Why not us?" But for one of them, the tide will soon turn and so, too, will the response: "Really? Us?" Yes, you. Imagine what that would feel like for Norman Rosen. He's 90 years old and wise to the patience required of Cubs fandom. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Football History Highlights

Football History Highlights Category: Group Activity Series: The NFL at a Glance (Amazing NFL Stories: 12 Highlights from NFL History) Supplies Multiple copies of Amazing NFL Stories: 12 Highlights from NFL History, access to Football history timeline: http://www.profootballhof.com/football-history/history-of-football/ Prep Ask students to read Amazing NFL Stories: 12 Highlights from NFL History or read it together as a class. Skim through the Football history timeline, using the attached Timeline Summary to note the most important events. Directions Ask the students to summarize a few of the chapters of Amazing NFL Stories. Help them notice the kinds of stories the chapters tell (a first-time accomplishment, a change in how the game was played, a rival league, or an all-time record). Split the students into six groups. Assign each group a date range: • 1869 to 1919 • 1960 to 1979 • 1920 to 1939 • 1980 to 1999 • 1940 to 1959 • 2000 to present (Note: On the Football History timeline, all events 1869 to 1939 are in the same category. Since that category is the longest, this activity splits it in half.) Have each group read all the events in their date range on the Football History timeline, looking for the kinds of key events that are described in Amazing NFL Stories. Each group should choose 8 years from their date range that they feel included the most important events. They should write down each year, along with a summary (two or three sentences) of the events that make it important. Evaluation Did the students correctly identify the most important events in their assigned date range? Give them 1 point for identifying each event and 2 points for summarizing it objectively. -

A Preliminary Container List

News and Communications Services Photographs (P 57) Subgroup 1 - Individually Numbered Images Inventory 1-11 [No images with these numbers.] 12 Kidder Hall, ca. 1965. 13-32 [No images with these numbers.] 33 McCulloch Peak Meteorological Research Station; 2 prints. Aerial view of McCulloch Peak Research Center in foreground with OSU and Corvallis to the southeast beyond Oak Creek valley and forested ridge; aerial view of OSU in foreground with McCulloch Peak to the northwest, highest ridge top near upper left-hand corner. 34-97 [No images with these numbers.] 98-104 Music and Band 98 3 majorettes, 1950-51 99 OSC Orchestra 100 Dick Dagget, Pharmacy senior, lines up his Phi Kappa Psi boys for a quick run-through of “Stairway to the Stars.” 101 Orchestra with ROTC band 102 Eloise Groves, Education senior, leads part of the “heavenly choir” in a spiritual in the Marc Connelly prize-winning play “Green Pastures,” while “de Lawd” Jerry Smith looks on approvingly. 103 The Junior Girls of the first Christian Church, Corvallis. Pat Powell, director, is at the organ console. Pat is a senior in Education. 104 It was not so long ago that the ambitious American student thought he needed a European background to round off his training. Here we have the reverse. With Prof. Sites at the piano, Rudolph Hehenberger, Munich-born German citizen in the country for a year on a scholarship administered by the U.S. Department of State, leads the OSC Men’s Glee Club. 105-106 Registrar 105 Boy reaching into graduation cap, girl holding it, 1951 106 Boys in line 107-117 Forest Products Laboratory: 107-115 Shots of people and machinery, unidentified 108-109 Duplicates, 1950 112 14 men in suits, 1949 115 Duplicates 116 Charles R. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. IDgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & HoweU Information Compaiy 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 OUTSIDE THE LINES: THE AFRICAN AMERICAN STRUGGLE TO PARTICIPATE IN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL, 1904-1962 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State U niversity By Charles Kenyatta Ross, B.A., M.A. -

2013 Steelers Media Guide 5

history Steelers History The fifth-oldest franchise in the NFL, the Steelers were founded leading contributors to civic affairs. Among his community ac- on July 8, 1933, by Arthur Joseph Rooney. Originally named the tivities, Dan Rooney is a board member for The American Ireland Pittsburgh Pirates, they were a member of the Eastern Division of Fund, The Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation and The the 10-team NFL. The other four current NFL teams in existence at Heinz History Center. that time were the Chicago (Arizona) Cardinals, Green Bay Packers, MEDIA INFORMATION Dan Rooney has been a member of several NFL committees over Chicago Bears and New York Giants. the past 30-plus years. He has served on the board of directors for One of the great pioneers of the sports world, Art Rooney passed the NFL Trust Fund, NFL Films and the Scheduling Committee. He was away on August 25, 1988, following a stroke at the age of 87. “The appointed chairman of the Expansion Committee in 1973, which Chief”, as he was affectionately known, is enshrined in the Pro Football considered new franchise locations and directed the addition of Hall of Fame and is remembered as one of Pittsburgh’s great people. Seattle and Tampa Bay as expansion teams in 1976. Born on January 27, 1901, in Coultersville, Pa., Art Rooney was In 1976, Rooney was also named chairman of the Negotiating the oldest of Daniel and Margaret Rooney’s nine children. He grew Committee, and in 1982 he contributed to the negotiations for up in Old Allegheny, now known as Pittsburgh’s North Side, and the Collective Bargaining Agreement for the NFL and the Players’ until his death he lived on the North Side, just a short distance Association. -

BA MSS 225 BL-225.2011 Title Larry Tye Research Papers

GUIDE to the LARRY TYE RESEARCH PAPERS National Baseball Hall of Fame Library Manuscript Archives National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 www.baseballhall.org Claudette Scrafford, Manuscript Archivist March 2014 Collection Number BA MSS 225 BL-225.2011 Title Larry Tye Research Papers Date Range 1880 - 2008 Extent 5.16 linear feet (14 archival boxes) Repository National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 Abstract A collection of newspaper and journal articles, book excerpts, interview transcripts, research notes, and correspondence related to Larry Tye’s book “Satchel: the life and times of an American Legend”. Preferred Citation Larry Tye Research Papers, BA MSS 225, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY Access By appointment during regular business hours, email [email protected]. Property Rights Property rights are owned by the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Provenance This collection was donated by the author Larry Tye in 2011. Biography From 1986 to 2001, Tye was a reporter at the Boston Globe, where his primary beat was medicine. He also served as the Globe’s environmental reporter, roving national writer, investigative reporter, and sports writer. Before that he was the environmental reporter at the Courier-Journal in Louisville, and covered government and business at the Anniston Star in Alabama. Tye’s book, Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend, is the biography of two American icons – Satchel Paige, arguably the greatest pitcher ever to throw a baseball, and Jim Crow, the amalgam of Southern laws that mandated separation of the races everywhere from public bathrooms to schools and buses. -

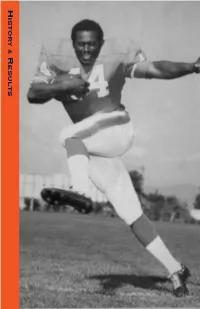

History and Results

H DENVER BRONCOS ISTORY Miscellaneous & R ESULTS Year-by-Year Stats Postseason Records Honors History/Results 252 Staff/Coaches Players Roster Breakdown 2019 Season Staff/Coaches Players Roster Breakdown 2019 Season DENVER BRONCOS BRONCOS ALL-TIME DRAFT CHOICES NUMBER OF DRAFT CHOICES PER SCHOOL 20 — Florida 15 — Colorado, Georgia 14 — Miami (Fla.), Nebraska 13 — Louisiana State, Houston, Southern California 12 — Michigan State, Washington 11 — Arkansas, Arizona State, Michigan 10 — Iowa, Notre Dame, Ohio State, Oregon 9 — Maryland, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Purdue, Virginia Tech 8 — Arizona, Clemson, Georgia Tech, Minnesota, Syracuse, Texas, Utah State, Washington State 7 — Baylor, Boise State, Boston College, Kansas, North Carolina, Penn State. 6 — Alabama, Auburn, Brigham Young, California, Florida A&M, Northwestern, Oklahoma State, San Diego, Tennessee, Texas A&M, UCLA, Utah, Virginia 5 — Alcorn State, Colorado State, Florida State, Grambling, Illinois, Mississippi State, Pittsburgh, San Jose State, Texas Christian, Tulane, Wisconsin 4 — Arkansas State, Bowling Green/Bowling Green State, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa State, Jackson State, Kansas State, Kentucky, Louisville, Maryland-Eastern Shore, Miami (Ohio), Missouri, Northern Arizona, Oregon State, Pacific, South Carolina, Southern, Stanford, Texas A&I/Texas A&M Kingsville, Texas Tech, Tulsa, Wyoming 3 — Detroit, Duke, Fresno State, Montana State, North Carolina State, North Texas State, Rice, Richmond, Tennessee State, Texas-El Paso, Toledo, Wake Forest, Weber State 2 — Alabama A&M, Bakersfield -

Gil Bouley 1945-50

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 9, No. 3 (1987) GIL BOULEY 1945-1950 By Joseph Hession Reprinted from Rams: Five Decades Of Football Gil Bouley remembers the 1945 NFL Championship Game as if it were yesterday. But then the game ranks as one of the most memorable title contests in league history, more for the bitter weather than the action on the playing field. Bouley was a rookie tackle for the Cleveland Rams that year. He joined the Rams after his outstanding college days at Boston College under the legendary Frank Leahy. In his first year with the club, he hit paydirt. The Rams ended the season with a 9-1 record, best in the NFL, then met the Washington Redskins for the championship. As game time approached, the temperature hovered around two degrees. Wind whipped off Lake Erie, dropping the wind chill factor to about 20 below zero. Grounds-keepers worked feverishly to clear the snow and ice that blanketed Cleveland's Municipal Stadium. Earlier in the week, bales of straw had been gathered from local farms and laid on the field to prevent it from freezing over. The straw had to be removed also. Municipal Stadium held over 80,000 fans and there was a pre- game sale of 40,000 tickets, yet only 32,178 showed up for the game. The strong north wind not only discouraged fans from attending, it played an important part in the game's outcome. The Rams won it, 15-14, but the margin of victory came in the first period when Sammy Baugh attempted to throw from his own end zone.